Abstract

Diseases associated with immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibody include linear IgA dermatosis, IgA nephropathy, Celiac disease, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, etc. Although usually idiopathic, IgA antibody is occasionally induced by drugs (e.g., vancomycin, carbamazepine, ceftriaxone, and cyclosporine), malignancies, infections, and other causes. So far, only a few cases of IgA bullous dermatosis coexisting with IgA nephropathy have been reported. A 64-year-old female receiving intravenous ceftriaxone and metronidazole for liver abscess had purpuric macules and papules on her extremities. One week later, she had generalized edema and skin rash with bullae and was diagnosed with concurrent linear IgA dermatosis and IgA nephropathy. After steroid treatment, the skin lesion subsided within two weeks, and kidney function slowly returned to normal. As both diseases occurred after a common possible cause, we predict their pathogeneses are associated.

Linear immunoglobulin A (IgA) bullous dermatosis (LABD) is a rare acquired autoimmune disease that results in subepidermal blisters, which are caused by IgA antibodies directed at target proteins within the epidermal adhesion complex. Although usually idiopathic, it is occasionally induced by drugs, internal malignancies, infection, etc1,2,3. Various drugs including acetaminophen, amiodarone, furosemide, phenytoin, ceftriaxone, and metronidazole can cause LABD. In particular, vancomycin is the most commonly associated etiologic drug4.

Reports of glomerulonephritis in patients with autoimmune bullous disease are increasing. However, only a few cases of LABD coexisting with IgA nephropathy have been reported. To our knowledge, no case of ceftriaxone- or metronidazole-induced LABD accompanied by IgA nephropathy has been reported. Here, we report the case of a 64-year-old woman diagnosed with concurrent drug-induced LABD (DLABD) and IgA nephropathy most probably due to ceftriaxone or metronidazole administration. We also review the relevant literature.

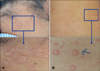

A 64-year-old female received intravenous ceftriaxone and metronidazole for liver abscess. One week later, she developed purpuric macules and papules on the upper and lower extremities. Because of suspected allergic vasculitis, she was treated with oral dapsone and methylprednisolone; the lesions subsided within a few days. Two weeks after purpura onset, she presented with generalized edema and consequently underwent kidney biopsy. Four days later, a pruritic diffuse morbilliform rash that clinically resembled drug eruption appeared on the trunk. Blood eosinophil percentage increased from 1.9% to 20.0% within few days after onset. One week later, bullae appeared on both the axilla and neck (Fig. 1). Skin biopsy of the bullae showed subepidermal blisters on H&E stain (Fig. 2A, B). Direct immunofluorescence showed linear depositions of IgA along basement membrane (Fig. 2C). Meanwhile, in the kidney biopsy, H&E stain showed glomeruli with mesangial proliferation (Fig. 3A), and direct immunofluorescence showed diffuse mesangial IgA deposits (Fig. 3B). On the basis of the histological findings of the kidneys and skin, the patient was diagnosed with concurrent LABD and IgA nephropathy. Intravenous ceftriaxone and metronidazole were intermittently changed with oral cefixime and oral metronidazole but were stopped owing to liver abscess at week eight after bullae formation. Therefore, intravenous dexamethasone, steroid ointment, and dressing were administered immediately after bullae formation. To treat both the skin and kidneys, which were affect by IgA antibodies, oral prednisolone 60 mg daily was administered one week after bullae formation, replacing intravenous steroid treatment. Skin lesions subsided within two weeks, and the patient underwent routine follow-up for kidney function, which recovered slowly.

DLABD differs from idiopathic LABD. For example, in DLABD, the incidence of mucosal or conjunctival lesions is relatively low, while up to 40% of patients with idiopathic LABD have mucosal involvement5. Moreover, in DLABD, spontaneous remission occurs when the causative drugs are withdrawn, and immune deposits disappear as the lesions resolve6. In contrast, only 10% to 50% of patients with idiopathic LABD achieve spontaneous remission, and immune deposits persist after lesions resolve in some cases7. Patients with DLABD also tend to be older than patients with idiopathic LABD5.

The pathogenesis of DLABD remains unclear. However, drug-specific CD4+ T lymphocytes may play an important role. Lymphocytes associated with DLABD induced by ceftriaxone and metronidazole administration exhibit significantly increased secretion of interleukin (IL)-5 and interferon (IFN)-γ cytokines8. T-cell lymphokines, including IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, and transforming growth factor, can increase IgA synthesis, regulate IgA isotype switching, and contribute to IgA B-cell differentiation9. As a result, abnormal IgA antibodies may migrate towards the dermal-epidermal junction, causing inflammation and blisters; alternatively, they may form an immune complex with other serum proteins to become deposits in the renal mesangium, which can eventually cause glomerulonephritis.

Our patient presented with concurrent LABD and IgA nephropathy. Furthermore, considering her increased blood eosinophil percentage, prior bullae formation, advanced age, the absence of mucosal involvement, and clinical remission after the cessation of drugs, we postulate the cause was drug-induced rather than idiopathic. As both ceftriaxone and metronidazole are reported to cause DLABD and had a temporal relationship with respect to onset and resolution in our patient, they could be considered the responsible drugs in the present case.

The findings of the present case suggest the pathogeneses of LABD and IgA nephropathy are likely associated, because both occurred after a common possible cause. In IgA nephropathy, IFN-γ and IL-4 gene polymorphisms with certain significantly increased genotype frequencies can influence disease susceptibility and progression in IgA nephropathy10. In addition, immune complexes from patients with IgA nephropathy can induce human mesangial cells to release factors such as tumor necrosis factor alpha, IL-6, and transforming growth factor, which can affect podocyte gene expression and glomerular permeability10. On the basis of the abovementioned pathogenesis of LABD and IgA nephropathy, IL-4, IL-6, transforming growth factor, and IFN-γ may play roles in both DLABD and IgA nephropathy. IFN-γ, which is reported to be elevated in DLABD caused by ceftriaxone and influence the disease progression of IgA nephropathy, may have played a major role in the pathogenesis of our patient. If the role of IFN-γ is clarified in further investigations, IFN-γ antibodies may be evaluated in clinical trials as an alternative treatment option for concurrent LABD and IgA nephropathy.

This case advances our understanding of the pathogenesis of concurrent LABD and IgA nephropathy, contributing to future investigations and the development of specifically targeted treatment options for these diseases.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Multiple scattered bullae on an erythematous base on the nape (A) and back (B) (arrow: biopsy site).

Fig. 2

(A) Subepidermal blister with inflammatory cell infiltration (H&E, ×100). (B) Polymorphonuclear leukocytes and few lymphocytes along the interface of the subepidermal blister and papillary dermis (H&E, ×400). (C) Linear deposition of immunoglobulin A along basement membrane (direct immunofluorescence, ×100).

References

1. Geissmann C, Beylot-Barry M, Doutre MS, Beylot C. Drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995; 32:296.

2. Holló P, Preisz K, Nemes L, Bíró J, Kárpáti S, Horváth A. Linear IgA dermatosis associated with chronic clonal myeloproliferative disease. Int J Dermatol. 2003; 42:143–146.

3. Blickenstaff RD, Perry HO, Peters MS. Linear IgA deposition associated with cutaneous varicella-zoster infection: a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 1988; 15:49–52.

4. Onodera H, Mihm MC Jr, Yoshida A, Akasaka T. Drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis. J Dermatol. 2005; 32:759–764.

5. Waldman MA, Black DR, Callen JP. Vancomycin-induced linear IgA bullous disease presenting as toxic epidermal necrolysis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004; 29:633–636.

6. Baden LA, Apovian C, Imber MJ, Dover JS. Vancomycin-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1988; 124:1186–1188.

7. Wojnarowska F, Marsden RA, Bhogal B, Black MM. Chronic bullous disease of childhood, childhood cicatricial pemphigoid, and linear IgA disease of adults. A comparative study demonstrating clinical and immunopathologic overlap. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988; 19:792–805.

8. Yawalkar N, Reimers A, Hari Y, Hunziker T, Gerber H, Müller U, et al. Drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis associated with ceftriaxone- and metronidazole-specific T cells. Dermatology. 1999; 199:25–30.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download