Abstract

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, known as malignant fibrous histiocytoma, is a malignant neoplasm that arises in both soft tissue and bones. In 2002, the World Health Organization declassified malignant fibrous histocytoma as a formal diagnostic entity and renamed it 'undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma not otherwise specified.' It most commonly occurs in the lower extremities and rarely metastasizes cutaneously. We report a case of cutaneous metastatic undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma of the buttocks occurring in a 73-year-old man diagnosed with mediastinal sarcoma 4 years previously. He first noticed the mass approximately 2 months previously. Histological findings with immunomarkers led to a final diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic sarcoma from mediastinal undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma.

Sarcomas can be classified as liposarcomas, fibrosarcomas, pleomorphic sarcomas, leiomyosarcomas, rhabdomyosarcomas, angiosarcomas, or osteosarcomas1. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas are a group of pleomorphic high-grade sarcomas that cannot be classified into any other subtype1,2. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas, known as malignant fibrous histiocytoma, is a malignant neoplasm that arises both in soft tissue and bones1,3. Histopathologically, it is described as an undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma characterized by atypical pleomorphic spindle tumor cells with a storiform growth pattern3. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas account for 5% of adult soft tissuesarcomas4. They predominantly present in the 5th to 7th decades of life and occur most frequently in the lower extremities3. Although undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma has high incidences of local recurrence and metastasis, to our knowledge, only 10 cases of cutaneous metastasis have been reported. Here, we report a case of cutaneous metastatic undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma on the right buttock area arising from a mediastinum sarcoma and review the relevant literature.

A 73-year-old man visited our department with a 3.0×3.5 cm deep seated nontender tumor on his buttock. He had a history of mediastinal sarcoma that had been excised 4 years previously. At that time, the tumor was a sarcoma with fibrotic and myxoid feature; it was excised completely, and the resection margin was clear. Thereafter, he was followed up by computed tomography (CT) without any recurrence. About 5 months previously, he complained of chest pain. CT showed a 12 cm mass in the left hemithorax with chest wall invasion and mediastinal mass excision was consequently performed. During follow-up, bone scintigraphy showed skeletal metastasis of the left 6th to 7th rib lateral arcs, and positron emission tomography CT showed reactive mediastinal lymph nodes.

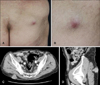

Therefore, the patient was treated with the following radiation schedule: X-rays, 180 cGy per fraction, and a total dose of 5,940 cGy. The patient was subsequently treated with 2 cycles of doxorubicin and ifosfamide. Meanwhile, a tumor was observed on the buttock and he was referred to us. On physical examination, the tumor on the right buttock appeared as a deep seated nodule (Fig. 1A, B). CT showed a 3×4 cm irregularly shaped soft tissue mass in the subcutaneous layer of his right buttock (Fig. 1C, D).

Histopathological examination of the tumor showed spindle-shaped cells arranged in a storiform pattern as well as atypical mitoses and pleomorphism. Immunohistochemistry revealed the tumor cells were positive for vimentin and Ki-67 (30%) but negative for CK7, CK19, EMA, S-100 protein, CD34, bcl-2, and CD99 (Fig. 2).

We diagnosed the tumor as cutaneous metastatic undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. The patient was subsequently referred to the Department of General Surgery. The tumor was excised completely with a clear resection margin, and he was treated with chemotherapy using pazopanib.

The local recurrence rate of undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas is 19% to 31%, and the metastasis rate is 31% to 35% after tumor resection with a clear resection margin5. Despite the high distant metastasis rate, cutaneous metastasis is very rare.6 The most common sites of metastasis are the lungs (90%), bone (8%), and liver (1%)5,6. Meanwhile, the cutaneous metastasis rate is 0.6% to 1.5%7,8. To our knowledge, only 10 cases of cutaneous metastasis have been reported (Table 1)5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Clinically, patients complain of a mass appearing rapidly, ranging from weeks to months13. Furthermore, the mass is usually asymptomatic13. In the present case, the patient did not complain of pain. Histologically, undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma is characterized by the presence of spokes of a wheel-like structure, showing spindle-shaped cells such as fibrocytes and histiocytes arranged in a storiform pattern3,5,14. Numerous giant cells show eosinophilic cytoplasm on staining; single or multiple irregular nuclei are observed, with inflammatory cells often mixing with the tumor cells13. In the present case, spindle-shaped cells were arranged in a storiform pattern and numerous pleomorphic cells with high mitotic rates were observed. Immunohistochemical staining for vimentin and CD68 is usually positive14. Moreover immunohistochemical staining for calretinin, cytokeratin, TTF-1, CD56, LCA, CD34, and S-100 proteinare negative14. However, there is no specific immunohistochemical stain that confirms the diagnosis15. The present case was positive for vimentin and Ki-67 (30%), and negative for CK7, CK19, EMA, S-100 protein, bcl-2, and CD99.

The differential diagnosis includes metaplastic (sarcomatoid) carcinoma, fibrosarcoma and other tumors such as malignant phyllodes tumor, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, and dermatofibrosarcoma1,5. Metaplastic (i.e., sarcomatoid) carcinoma, also called spindle cell carcinoma, is confirmed by CK positivity1. However, the present case, was negative for CK. Fibrosarcoma is another differential diagnosis but is less pleomorphic5.

Cutaneous metastatic undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma is important because the prognosis can be very poor5,6. Among the 10 reported cases of cutaneous metastases, the survival period is only reported in 4; the average survival period in 3 patients was 8 to 14 weeks5,8,9, whereas the other patient was alive for 2 years6.

Interestingly, in the present case, the metastatic site was the buttock which is the most common intramuscular injection site. Although there was no evidence that the metastatic site was exactly the injection site, he complained of a mass after injection, followed by rapid tumor growth. Thus, it is possible the trauma caused by the injection was the trigger factor. In previous case reports, undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma was associated with burn, radiotherapy, and vaccination scars; a chronic ulcer at a fracture site; and a skin-graft donor site16. Thus, it is interesting that undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma occurred at an intramuscular injection site in the present case.

The treatment of choice for undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma is wide excision. Adjuvant radiotherapy is sometimes effective, and adjuvant chemotherapy can be performed in cases of multiple metastases8. In the present case, the tumor was completely excised with a clear resection margin, and chemotherapy with pazopanib was performed.

As cutaneous metastatic undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma is rare most clinicians do not have experience diagnosing this disease, which may result in a late diagnosis. Therefore, further study of this tumor is important, and the case reported herein expands knowledge about this tumor.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

(A) A solitary hard deep seated nodule in the right buttock. (B) Close-up of the nodule in (A). Axial (C) and sagittal (D) computed tomography images showing a 3×4 cm irregularly shaped metastatic soft tissue mass in the subcutaneous layer of the right buttock.

Fig. 2

The mediastinal tumor 4 years previously (H&E; A: ×12.5, B: ×200). The tumor was composed of spindle-shaped cells arranged in a storiform pattern with atypical mitoses the same findings were observed in the mediastinal tumor upon recurrence (H&E; C: ×12.5, D: ×400) and metastatic tumor in the buttock (H&E; E: ×12.5, F: ×400).

References

1. Jeong YJ, Oh HK, Bong JG. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma of the male breast causing diagnostic challenges. J Breast Cancer. 2011; 14:241–246.

2. Kauffman SL, Stout AP. Histiocytic tumors (fibrous xanthoma and histiocytoma) in children. Cancer. 1961; 14:469–482.

3. Tilkorn DJ, Daigeler A, Hauser J, Ring A, Stricker I, Schmitz I, et al. A novel xenograft model with intrinsic vascularisation for growing undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma NOS in mice. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012; 138:877–884.

4. Fletcher CD. The evolving classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the new WHO classification. Histopathology. 2006; 48:3–12.

5. Suzuki S, Watanabe S, Kato H, Inagaki H, Hattori H, Morita A. A case of cutaneous malignant fibrous histiocytoma with multiple organ metastases. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2013; 29:111–115.

6. Lew W, Lim HS, Kim YC. Cutaneous metastatic malignant fibrous histiocytoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003; 48:2 Suppl. S39–S40.

7. Weiss SW, Enzinger FM. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma: an analysis of 200 cases. Cancer. 1978; 41:2250–2266.

8. Kim JB, Kim JH, Kim HJ, Kim HK, Ko YS, Lee JS, et al. A case of malignant fibrous histiocytoma that metastasized to the skin. Korean J Dermatol. 2009; 47:75–79.

9. Enion DS, Scott MJ, Gouldesbrough D. Cutaneous metastasis from a malignant fibrous histiocytoma to a limb skin graft donor site. Br J Surg. 1993; 80:366.

10. Kearney MM, Soule EH, Ivins JC. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma: a retrospective study of 167 cases. Cancer. 1980; 45:167–178.

11. Chen KT. Scalp metastases as the initial presentation of malignant fibrous histiocytoma. J Surg Oncol. 1984; 27:179–180.

12. Geist J, Azzopardi M, Domanowski A, Plezia R, Venkat H. Thoracic malignant fibrous histiocytoma metastatic to the tongue and skin of the face. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990; 69:199–204.

13. Liu C, Zhao Z, Zhang Q, Wu Y, Jin F. Primary malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the breast: report of one case. Onco Targets Ther. 2013; 6:315–319.

14. Cho KH, Park C, Hwang KE, Hwang YR, Seol CH, Choi KH, et al. Primary malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the pleura. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2013; 74:222–225.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download