Abstract

Background

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is chronic seronegative inflammatory arthritis that causes irreversible joint damage. Early recognition of PsA in patients with psoriasis is important for preventing physical disability and deformity. However, diagnosing PsA in a busy dermatology outpatient clinic can be difficult.

Objective

This study aimed to validate the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation (PASE) questionnaire for the detection of PsA in Korean patients with psoriasis.

Methods

The PASE questionnaire was prospectively given to 148 patients diagnosed with psoriasis but without a previous diagnosis of PsA. All patients underwent radiologic and laboratory examinations, and a subsequent clinical evaluation by a rheumatologist.

Results

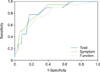

Eighteen psoriasis patients (12.2%) were diagnosed with PsA according to the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis. The PASE questionnaire scores of differed significantly between PsA and non-PsA patients. Receiver operator characteristic analysis showed an area under the curve of 0.82 (95% confidence interval: 0.72, 0.92) for PASE score. A PASE score cut-off of 37 points had a sensitivity of 77.8% and specificity of 82.3% for the diagnosis of PsA.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a type of inflammatory arthritis that causes irreversible joint damage. The major signs and symptoms of PsA include sacroiliitis, dactylitis, and enthesitis1. However, it is impossible for dermatologists in busy clinics to perform detailed joint examinations for all psoriasis patients to diagnose PsA. However, dermatologists are in an excellent position to make an early diagnosis and provide appropriate treatment, which would minimize progressive damage. Therefore, a simple screening tool is required to enable dermatologists to detect PsA at an early stage. Several screening tools such as the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening project2, the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation (PASE)3, and the early arthritis for psoriatic patients4 have been reported in foreign literature. Among them, the PASE questionnaire is a well-validated self-administered screening tool that can be used to screen for patients with psoriasis. Accordingly, this study validated the PASE questionnaire for the detection of PsA in Korean patients with psoriasis in a dermatologic outpatient clinic setting.

Patients with a diagnosis of psoriasis but without a previous diagnosis of PsA who had completed the PASE questionnaire3 during clinical presentation at Pusan National University Hospital between January 2011 and August 2013 were included in this study. The included patients had never been treated with any disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs for psoriasis. All patients underwent radiologic examinations (i.e., spine, hand, foot, pelvis, and knee) and laboratory exams (i.e., complete blood count, liver and renal function tests, venereal disease research laboratory test, rheumatoid factor, uric acid, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and fluorescent antinuclear antibody test). The Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) score was determined in each case. Psoriasis was diagnosed by a dermatologist on the basis of the results of clinical and histologic examinations. A final diagnosis of PsA was made by a rheumatologist on the basis of the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis5. Patients were recruited from a dermatology outpatient clinic.

This study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Pusan National University (No. E2014088).

The original PASE questionnaire was translated from English into Korean and then back into English with no appreciable differences. The Korean PASE questionnaire comprises 15 items divided into two subscales: a seven-item symptom scale and an eight-item function scale. There were five possible answers to each question (1~5) related to the level of agreement (i.e., 5, strongly agree; 4, agree; 3, neutral; 2, disagree; and 1, strongly disagree). Questionnaire scores were calculated by summing responses to the 15 questions and ranged from 15 to 75 points. The maximum PASE symptom and function scores were 35 and 40, respectively.

Only patients who completed the questionnaire were included in the analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using PASW Statistics ver. 18.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). The level of significance was set at p<0.05. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test, the χ2 test, or Fisher's exact test was used to test for differences between the PsA and non-PsA groups with respect to clinical characteristics, total, function, and symptom PASE scores and PASI scores. Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves were calculated to determine the optimal cut-off total PASE score for predicting PsA. The sensitivities and specificities of several total PASE cut-off values were determined.

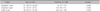

A total of 148 psoriasis patients were included in the present study, and 18 (12.2%) were diagnosed with PsA. The most common pattern according to the criteria of Moll and Wright6 was asymmetric oligoarthritis (11/18, 61.1%), followed by spondylitis (4/18, 22.2%) and distal interphalangeal predominant (3/18, 16.7%). The clinical characteristics of the 148 psoriasis patients are summarized in Table 1. The prevalences of dactylitis and sacroiliitis were significantly higher among patients with PsA. There was no association between PASI score and the presence/absence of PsA.

However, the PASE scores differed significantly between the PsA and non-PsA groups (Table 2). Patients with PsA had significantly higher symptom, function, and total PASE scores. Response scores to 14 of the 15 questions of the PASE differed significantly between the PsA and non-PsA groups; only responses to question 1, "I feel tired for most of the day," did not differ significantly (data not shown).

Total PASE scores ranged 15 to 72, and a total PASE score of 37 was found to be the optimal cut-off for differentiating between PsA and non-PsA patients by ROC analysis. At this cut-off, the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of the PASE were 77.8% and 82.3%, respectively (Fig. 1), with positive and negative predictive values of 37.8% and 96.4%, respectively.

Between 8% and 30% of patients with psoriasis develop PsA and require care for both skin and joint involvement7,8. Fleischer et al.9 report that 69% of patients with psoriasis vulgaris suffer from joint pain. However, despite the high incidence of PsA, dermatologists cannot perform full physical and laboratory examinations for all psoriasis patients because of demanding outpatient clinic schedules. Although several questionnaires have been developed to screen for PsA, they are rarely used in Korean dermatologic clinics. However, the PASE questionnaire has been validated in a large study of patients with psoriasis in a combined dermatology-rheumatology clinical setting10. Walsh et al.11 report that the PASE questionnaire has the highest sensitivity and specificity when applied to patients not on systemic therapy; they also found that it was easily administered in outpatient clinics. Therefore, we administered the PASE questionnaire to detect PsA and help determine the prevalence of PsA in specific populations.

The diagnosis of PsA is difficult, because there is no specific diagnostic test. Diagnoses are made primarily on the basis of clinical features as well as laboratory and radiologic findings. The clinical signs and symptoms of PsA include dactylitis, enthesitis, spinal inflammation, and asymmetric joint involvement12. Therefore, we performed physical, laboratory, and radiologic testing on all psoriasis patients to investigate the relationships of PsA and test results with PASE scores. The prevalences of dactylitis and sacroiliitis were significantly higher in patients with PsA, which is concordant with previous studies13,14. Therefore, dermatologists should be aware of these symptoms in suspected cases.

In the present study, a total PASE score of 37 or more detected 77.8% of true-positives cases of PsA (i.e., sensitivity of 77.8%); this indicates further evaluation is required to accurately diagnose PsA. The sensitivity and specificity of this PASE cut-off are similar to those in previous studies3 using the PASE but with different cut-offs. Husni et al.3 report that a total PASE score of 47 was able to differentiate between PsA and non-PsA patients with a sensitivity and specificity of 82% and 73%, respectively. This large difference in cut-offs between studies can be explained by the influences of factors such as ethnicity, populations, health status, and employment type. The Korean PASE missed 4 of the 18 patients with PsA who had a total score less than 37. On the other hand, only 14 of the 37 patients with a score more than 37 were diagnosed with PsA. The other 23 were diagnosed with osteoarthritis, spondylosis, and other spondyloarthropathies by a rheumatologist. Thus, although a high PASE score indicates a greater probability of PsA, it is still difficult for dermatologists to distinguish PsA from other types of inflammatory arthritis by using this metric.

PsA is fairly common among Korean patients with psoriasis and results in impaired physical function and disability. The present study shows that the adoption of the PASE questionnaire for screening psoriasis outpatients could substantially improve early PsA diagnosis. Furthermore, the results indicate a cut-off of 37 points is appropriate for screening Korean patients with psoriasis, with a sensitivity of 77.8% and specificity of 82.3%. Nevertheless, additional large multicenter studies are required in Korea to confirm our results. Finally, we hope that this study increases interest in PsA in the dermatology community.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Receiver operator curves (ROC) curves for total, symptom, and functional Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Evaluation (PASE) scores. *ROC were used to identify the optimal cut-off of the total PASE score. |

References

1. Helliwell PS, Taylor WJ. Classification and diagnostic criteria for psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005; 64:Suppl 2. ii3–ii8.

2. Ibrahim GH, Buch MH, Lawson C, Waxman R, Helliwell PS. Evaluation of an existing screening tool for psoriatic arthritis in people with psoriasis and the development of a new instrument: the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) questionnaire. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009; 27:469–474.

3. Husni ME, Meyer KH, Cohen DS, Mody E, Qureshi AA. The PASE questionnaire: pilot-testing a psoriatic arthritis screening and evaluation tool. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007; 57:581–587.

4. Tinazzi I, Adami S, Zanolin EM, Caimmi C, Confente S, Girolomoni G, et al. The early psoriatic arthritis screening questionnaire: a simple and fast method for the identification of arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012; 51:2058–2063.

5. Tillett W, Costa L, Jadon D, Wallis D, Cavill C, McHugh J, et al. The ClASsification for Psoriatic ARthritis (CASPAR) criteria--a retrospective feasibility, sensitivity, and specificity study. J Rheumatol. 2012; 39:154–156.

7. Wilson FC, Icen M, Crowson CS, McEvoy MT, Gabriel SE, Kremers HM. Time trends in epidemiology and characteristics of psoriatic arthritis over 3 decades: a population-based study. J Rheumatol. 2009; 36:361–367.

9. Fleischer AB Jr, Feldman SR, Rapp SR, Reboussin DM, Exum ML, Clark AR, et al. Disease severity measures in a population of psoriasis patients: the symptoms of psoriasis correlate with self-administered psoriasis area severity index scores. J Invest Dermatol. 1996; 107:26–29.

10. Qureshi AA, Dominguez P, Duffin KC, Gladman DD, Helliwell P, Mease PJ, et al. Psoriatic arthritis screening tools. J Rheumatol. 2008; 35:1423–1425.

11. Walsh JA, Callis Duffin K, Krueger GG, Clegg DO. Limitations in screening instruments for psoriatic arthritis: a comparison of instruments in patients with psoriasis. J Rheumatol. 2013; 40:287–293.

12. Mease P, Goffe BS. Diagnosis and treatment of psoriatic arthritis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005; 52:1–19.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download