Abstract

Amelanotic acral melanoma is rare and difficult to diagnose, both clinically and pathologically. KIT mutations are frequently found in acral melanomas and are considered a risk factor for poor prognosis. The presence of vitiligo in melanoma has been reported, and KIT is thought to be partly responsible for the dysfunction and loss of melanocytes observed in vitiligo. We report a case of amelanotic subungual melanoma with multiple metastases that was associated with KIT mutation and vitiligo. An 85-year-old man presented with a 3-year history of a tender erythematous ulcerated tumor on the left third fingertip and developed hypopigmented patches on the face and trunk. Histopathological examination of the ulcerative tumor showed aggregates of tumor cells that were pleomorphic epithelioid cells. Immunohistochemical staining of the tumor cells was positive for S100, HMB45, and c-Kit. Histopathological findings from the hypopigmented patch on the face were consistent with vitiligo. Mutation analysis showed a KIT mutation in exon 17 (Y823D). The patient had metastasis to the brain, liver, bone, and both lungs. The patient refused chemotherapy, and died 3 months after the first visit.

Amelanotic melanoma is a subtype of melanoma with little or no pigmentation. It represents 2%~8% of all melanomas. It is also frequently mistaken clinically as a non-melanocytic neoplasm or dermatitis, possibly resulting in a delayed diagnosis1,2. Acral melanoma is the most common type of melanoma in Asians and it typically has a poor prognosis3. Amelanotic acral melanoma (AAM) is rare and difficult to diagnose clinically and pathologically, and mimics benign diseases such as calluses, warts, nonhealing ulcers, and nail lichen planus4. Recent molecular classification of melanomas has revealed that KIT mutations and/or increased copy numbers are frequently found in mucosal and acral melanomas5. KIT mutations were found to be an independent risk factor for a poor prognosis, and patients with KIT mutations had poorer survival compared with those without KIT mutations6. KIT exerts multiple effects in melanocytes, and is thought to be partly responsible for the dysfunction and/or loss of melanocytes in patients with vitiligo7. The occurrence of vitiligo in melanoma patients has been reported, and is considered a consequence of the immune response against antigens shared by normal melanocytes and melanoma cells. In some reports, melanoma-associated vitiligo was associated with a favorable prognosis8,9. Here, we present a case of amelanotic subungual melanoma with multiple metastases that was associated with KIT mutation and vitiligo.

An 85-year-old man presented with a 3-year history of a tender, erythematous, ulcerated tumor on the left third fingertip. A subungual, skin-colored papule had developed initially, and slowly increased in size over time, followed by the development of ulceration. Physical examination showed a large, erythematous, ulcerated tumor on the fingertip, 2.5×2×1 cm in size, which was accompanied by nail destruction (Fig. 1A, B). The dermoscopic features of the tumor showed a uniformly reddish asymmetric patch with an ill-defined border. Additionally, the patient developed hypopigmented patches on the face and trunk that had first appeared 2 years after the appearance of the tumor (Fig. 1C). Symmetrically depigmented patches were accentuated under a Wood's light lamp, and consistent with classic vitiligo. Five months prior, the patient had also observed a protruding subcutaneous nodule on the dorsum of the left hand, and right hemiparesis with dementia had recently developed.

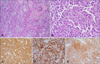

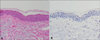

Histopathological examination of the ulcerative tumor on the fingertip showed aggregates of tumor cells that almost occupied the dermis, and solitary cells were distributed along the basal layer. The tumor cells were identified as pleomorphic epithelioid cells with clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm, which were suggestive of malignant melanoma (Fig. 2A, B). In immunohistochemical staining, the tumor cells stained positive for S100, HMB45, and c-Kit (Fig. 2C~E). We diagnosed the patient with an ulcerated subungual melanoma. The Breslow thickness was 7.25 mm; the mitotic count was 15/mm2; and the vertical growth phase had a Clark level of at least IV. Regression, microsatellites, vascular invasion, and precursor lesions were not observed. A biopsy specimen from the protruding nodule on the dorsum of the hand showed a bulky tumor nodule composed of pleomorphic epithelioid cells that stained positive for S100 and HMB45. The nodule was considered a metastatic melanoma. Histopathological findings from the hypopigmented patch on the face showed a complete absence of melanin and melanocytes, and immunohistochemical staining was negative for Melan-A (Fig. 3).

In laboratory tests, the patient showed elevated aspartate aminotransferase (66 U/L) and lactate dehydrogenase (1,332 IU/L) levels. Whole-body positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) and brain CT were performed for the evaluation of metastasis and revealed widespread metastasis to the brain, liver, bone, and both lungs. In mutation analysis of the ulcerative tumor, KIT mutation was detected in exon 17 (Y823D) (Fig. 4).

The patient was diagnosed with amelanotic subungual melanoma (stage IV) associated with KIT mutation and vitiligo. The patient refused chemotherapy, and died 3 months after his first visit.

AAM is a true diagnostic challenge, with little or no pigment at visual inspection. AAM presents as erythematous plaques or nodules and is often misdiagnosed as a benign disease. Therefore, it tends to have a poor prognosis because of the diagnosis at advanced stages. Microscopically, AAM is often classified as a nodular melanoma, with a high Breslow thickness and significant mitotic activity. It's biological behavior may be intrinsically more aggressive than that of conventional pigmented melanomas10. The histopathological features of AAM are variable and challenging to define, and can be difficult to differentiate from other tumors such as desmoplastic, neurotropic, histiocytic, and small-cell variants.

Recent molecular classification of melanomas has revealed that BRAF and NRAS mutations are common in melanomas on skin without chronic sun-induced damage, whereas KIT mutations and/or increased copy number are frequently found in mucosal and acral melanomas5,11. KIT mutations and increased KIT copy numbers were identified in 7.3% and 20.9% of acral melanomas, respectively; whereas in AAM, KIT mutations were identified in 12.1% of cases, and increased KIT copy numbers were identified in 27.3% of cases4,6. These results suggest that KIT aberrations occur more frequently in AAM than in pigmented acral melanomas. KIT mutations were found to be an independent risk factor for poor prognosis. An overall survival curve of patients with KIT mutations showed they had a significantly poorer survival rate than those without KIT mutations. In previous study, AAM showed a poor survival curve with a mean survival time of 30.14±4.54 months6. Imatinib (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor) demonstrated significant activity in patients with metastatic melanoma harboring a genetic KIT aberration with an overall response rate of 23.3%12. We expect that tyrosine kinase inhibitors would be effective in patients with KIT-mutated AAMs, including this patient, but this trial was not carried out.

The development of vitiligo in melanoma patients is well-documented but the pathogenesis is poorly understood. The association between melanoma and vitiligo is considered a consequence of the immune-mediated response against antigens shared by normal melanocytes and melanoma cells13. KIT encodes a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor and exerts multiple down-regulated effects in melanocytes, including migration, survival, proliferation, and differentiation14. KIT is thought to be partly responsible for the dysfunction and/or loss of melanocytes in patients with vitiligo, and KIT mutations are known as the basis for human piebaldism15. Therefore, we hypothesized that the presentation of vitiligo in this patient could be the result of a KIT mutation. Quaglino et al.8 reported that 2.8% of melanoma patients exhibited vitiligo and that these patients had a favorable prognosis. However, the prognostic value of vitiligo in melanoma was reported to be inconsistent among previous reports. Considering the function of the KIT protein and the high prevalence of KIT mutations in AAM, we assume that melanomas with KIT mutation are predominantly of the AAM subtype, and are also associated with vitiligo. Although a favorable prognosis has been reported with melanoma-associated vitiligo, AAM-associated vitiligo could be expected to have a poor prognosis due to high prevalence of KIT mutations. Silver et al.16 reported a case of AAM-associated vitiligo with poor prognosis. However, more cases and a large scale study are needed to confirm this.

In the presented case, we encountered the terminal stage of an amelanotic subungual melanoma with multiple metastases that was associated with KIT mutation and vitiligo. Physicians should be aware of the rare occurrence of AAMs, and consider AAM in the differential diagnosis when amelanotic tumors appear at acral sites.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1(A, B) An erythematous ulcerated tumor on the fingertip and a protruding subcutaneous nodule on the dorsum of the hand. (C) Hypopigmented patches on the face. |

| Fig. 2(A, B) Biopsy of the ulcerative tumor on the fingertip shows sheet-like arrangements of pleomorphic atypical tumor cells (H&E; A: ×100, B: ×400). (C~E) In immunohistochemical staining, tumor cells stained positive for S100 (C: ×200), HMB45 (D: ×200), and c-Kit (E: ×200). |

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by Leading Foreign Research Institute Recruitment Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MEST) (2011-0030034).

References

1. Pizzichetta MA, Talamini R, Stanganelli I, Puddu P, Bono R, Argenziano G, et al. Amelanotic/hypomelanotic melanoma: clinical and dermoscopic features. Br J Dermatol. 2004; 150:1117–1124.

2. Cheung WL, Patel RR, Leonard A, Firoz B, Meehan SA. Amelanotic melanoma: a detailed morphologic analysis with clinicopathologic correlation of 75 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2012; 39:33–39.

3. Kuchelmeister C, Schaumburg-Lever G, Garbe C. Acral cutaneous melanoma in caucasians: clinical features, histopathology and prognosis in 112 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2000; 143:275–280.

4. Choi YD, Chun SM, Jin SA, Lee JB, Yun SJ. Amelanotic acral melanomas: clinicopathological, BRAF mutation, and KIT aberration analyses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013; 69:700–707.

5. Curtin JA, Busam K, Pinkel D, Bastian BC. Somatic activation of KIT in distinct subtypes of melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006; 24:4340–4346.

6. Jin SA, Chun SM, Choi YD, Kweon SS, Jung ST, Shim HJ, et al. BRAF mutations and KIT aberrations and their clinicopathological correlation in 202 Korean melanomas. J Invest Dermatol. 2013; 133:579–582.

7. Kitamura R, Tsukamoto K, Harada K, Shimizu A, Shimada S, Kobayashi T, et al. Mechanisms underlying the dysfunction of melanocytes in vitiligo epidermis: role of SCF/KIT protein interactions and the downstream effector, MITF-M. J Pathol. 2004; 202:463–475.

8. Quaglino P, Marenco F, Osella-Abate S, Cappello N, Ortoncelli M, Salomone B, et al. Vitiligo is an independent favourable prognostic factor in stage III and IV metastatic melanoma patients: results from a single-institution hospitalbased observational cohort study. Ann Oncol. 2010; 21:409–414.

9. Boasberg PD, Hoon DS, Piro LD, Martin MA, Fujimoto A, Kristedja TS, et al. Enhanced survival associated with vitiligo expression during maintenance biotherapy for metastatic melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2006; 126:2658–2663.

10. Massi D, Pinzani P, Simi L, Salvianti F, De Giorgi V, Pizzichetta MA, et al. BRAF and KIT somatic mutations are present in amelanotic melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2013; 23:414–419.

11. Hong JW, Lee S, Kim DC, Kim KH, Song KH. Prognostic and clinicopathologic associations of BRAF mutation in primary acral lentiginous melanoma in Korean patients: a preliminary study. Ann Dermatol. 2014; 26:195–202.

12. Guo J, Si L, Kong Y, Flaherty KT, Xu X, Zhu Y, et al. Phase II, open-label, single-arm trial of imatinib mesylate in patients with metastatic melanoma harboring c-Kit mutation or amplification. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29:2904–2909.

13. Wankowicz-Kalinska A, Le Poole C, van den Wijngaard R, Storkus WJ, Das PK. Melanocyte-specific immune response in melanoma and vitiligo: two faces of the same coin? Pigment Cell Res. 2003; 16:254–260.

14. Han H, Yu YY, Wang YH. Imatinib mesylate-induced repigmentation of vitiligo lesions in a patient with recurrent gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008; 59:5 Suppl. S80–S83.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download