Abstract

Background

The development of therapies for psoriasis has led to the need for a new strategy to the treatment of patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. New consensus guidelines for psoriasis treatment have been developed in some countries, some of which have introduced treatment goals to determine the timing of therapeutic regimens for psoriasis.

Objective

To investigate the opinions held by Korean dermatologists who specialize in psoriasis about treatment goals, and to compare these with the European consensus.

Methods

Korean dermatologists who specialize in psoriasis were asked 11 questions about defining the treatment goals for psoriasis. The questionnaire included questions about the factors used to classify the severity of psoriasis, defining the induction and maintenance phases of psoriasis treatment, defining treatment responses during the induction phase, and defining treatment responses during the maintenance phase.

Results

The Korean consensus showed responses that were almost similar to the European consensus, even without using the Delphi technique, which uses repeated rounds of questions to reach a consensus. Only one response that related to psoriasis severity in the context of the quality of patients' lives differed from the European consensus.

Conclusion

The concept of using treatment goals in the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis can be applied to Korean psoriasis patients. Since a tool for assessing the quality of patients' lives is not commonly used in Korea, the development of a simple, rapidly completed, and region-specific health-related quality of life assessment tool would enable treatment goals to be used in routine clinical practice.

Psoriasis is a chronic relapsing immune-mediated inflammatory disorder of the skin1,2. Treatment for psoriasis is often life long, and it needs to be adjusted over time to account for changes in severity3. To successfully manage psoriasis, good communication between doctors and patients is essential to ensure that patients are well informed about their condition and that they can communicate their concerns and expectations about the disorder and its treatment. Recently, new therapeutic modalities have been developed for patients who do not show good clinical improvements after conventional psoriasis treatments. The broader range of therapeutic options available for psoriasis has led to the development of psoriasis management guidelines, which reflect regional circumstances and the differences in each nation's healthcare system and policies. While we can readily access psoriasis treatment guidelines that have been developed by the USA, Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, the Nordic countries, and Japan4,5,6,7,8, these treatment guidelines do not describe how to decide when to change or stop treatments in sufficient detail, which creates problems when using these guidelines in clinical practice.

A new European consensus relating to treatment goals for moderate-to-severe psoriasis was introduced in 20119. In this consensus, the psoriasis area and severity index (PASI), a physician-conducted objective assessment of severity based on clinical criteria that include the body surface area (BSA) involved, and the dermatology life quality index (DLQI)10,11,12, a subjective measurement of severity that is depicted by patients, were primarily used to determine the success of therapy in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. The use of both of these measurements to decide when to change or stop certain treatment modalities is a novel concept in the treatment of psoriasis.

In Korea, we have not yet developed our own consensus guidelines for psoriasis treatment or reached consensus about region-specific treatment goals. Eight psoriasis specialists participated in this study to reach consensus about treatment goals that suit the Korean healthcare situation. The aim of this study was to compare the Korean dermatologists' perspectives with the European consensus and to lay a cornerstone for the development of Korean consensus guidelines for psoriasis treatment.

Eight Korean dermatologists who specialize in psoriasis completed the questionnaire. All of the participants gathered at the same location for a consensus conference. The participants answered 11 questions from the European consensus on psoriasis treatment goals using electronic voting software installed on iPads (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA). All participants voted on the same question simultaneously, and the results from the voting were projected on a screen immediately after the participants had answered the question. All of the participants then discussed their opinions about the displayed result. The Delphi technique, which was used to reach consensus from participants who had different views on the same questions in Europe, was not used in this consensus conference because the number of psoriasis specialists in Korea is too small for this technique to be effective and there were time constraints. There were four categories of questions about psoriasis treatment, namely, the classification of psoriasis severity, the definitions of the induction and maintenance phases for the systemic treatment of psoriasis, the definitions of treatment responses during the induction phase, and the definitions of treatment responses during the maintenance phase. The study was exempt from the institutional review board at the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (No. 406-53-903).

The responses to the 11 questions from the European consensus conference were compared with the Korean responses. The proportions of positive answers were calculated, and the differences between the European and Korean consensuses were compared. Fisher's exact test for independent variables was performed on each question using SPSS Statistics 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

In contrast to the European consensus, which used the Delphi technique to obtain a strong consensus in the final results, the Korean consensus conference did not use a repetitive voting technique. Most of the consensus questionnaire responses showed relatively weak agreements compared with the European consensus. However, most of the areas of agreement did not differ from those in the European consensus, despite the small number of participants and not using the Delphi technique.

The participants were asked three questions to define the concept of psoriasis severity in the context of clinical practice in Korea. The classification of psoriasis into mild versus moderate-to-severe psoriasis to provide guidance in relation to treatment modalities was agreed to by 62.5% of the participants (Table 1). The explanation given for disagreement was that this classification does not reflect the effects of psoriasis on particular locations, including the face, nails, scalp, and genitalia, because even mild psoriasis in these areas can have significant impacts upon on the health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Two questions considered the subjective impact of psoriasis on HRQoL, which did not correlate with the doctors' assessments. These questions asked about the classifications of mild psoriasis with a high impact on HRQoL, and severe psoriasis with a low impact on HRQoL. The agreement for considering a low PASI/BSA with high DLQI to be moderate to severe psoriasis was 62.5%, but only 37.8% agreed that a high PASI/BSA with low DLQI could be classified as mild psoriasis. In response to the former question, it was stated that due to differences in psoriasis severity from Caucasians, the suggested cut-off value for the BSA, 10%, is not appropriate for Korean patients. The last question in this part of the questionnaire was the only one that showed a statistically significant difference compared with the European consensus. The major reason for the objection was that it is impossible to achieve improvements while using topical medications on patients who have clinically severe psoriasis, irrespective of how minimally psoriasis affects a patient's quality of life.

When using systemic treatments for moderate-to-severe psoriasis, it can take a long time to assess the efficacy of a particular medication. Categorizing the treatment period into an induction phase and a maintenance phase can be helpful for scheduling or changing medications (Table 2). Of the participants, 62.5% agreed to a definition of the induction period as 16~24 weeks. The main reason underlying the objections to this definition was that many psoriasis medications can achieve noteworthy improvements within 12 weeks. All of the participants agreed with the concept of induction and maintenance phases. Most of the participants agreed that there was a need for the concept of a maintenance period in systemic treatment.

The questions relating to the definitions of treatment responses during the induction phase generated total agreement among all of the participants (Table 3). The response to treatment during the induction phase can be assessed using the PASI score. The treatment can be considered effective if the PASI score improves by 75% or more. If the PASI score improves by 50% or less, the current medication can be considered ineffective. In relation to the question about a borderline response, which is defined as an improvement in the PASI score of more than 50% but less than 70%, 87.5% of the participants agreed that this should be re-evaluated using the DLQI score. The reason given for the disagreement was that the DLQI is currently not commonly used in routine clinical practice.

The responses to the questions about the maintenance phase were almost the same as those to the questions about the induction phase, with the only difference relating to the continuation of a regimen after a PASI reduction of 75% had been achieved during the maintenance period (Table 4). In contrast to the induction phase, doctors always confront the decision of when to reduce or stop a regimen during the maintenance phase. Not all of the participants could agree on the necessity to continue a maintenance regimen after improvements.

Treatment guidelines or goals for chronic diseases should be individualized for each country, because disease characteristics and treatment patterns are not always the same among the different nations. Other countries' psoriasis treatment guidelines are readily accessible, and differences exist among the guidelines, which have been modified to suit a particular country's context.

Treatment guidelines have not yet been established for the management of psoriasis in Korea, and dermatologists only have insurance guidelines to direct the use of biologics in the treatment of psoriasis. These guidelines define phototherapy or conventional systemic medications as first-line modalities for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis, and biologics are only used as second-line treatments. However, there are no consensus-based concepts for psoriasis treatment goals, which are useful for guiding dermatologists in their decisions about patients who are in clinical remission, patients who are unresponsive to a therapy, and those individuals who are dissatisfied with their HRQoL13.

This consensus conference, which was the first to be held in Korea that was attended by psoriasis specialists, is a meaningful first step towards developing psoriasis treatment goals that are tailored for the Korean population. The most important new concept introduced during this consensus conference was the consideration of a patient's subjective feelings in relation to the quality of their lives, which was similar to the European consensus conference. We did not use the Delphi technique to reach a final consensus from the participants during this consensus conference because of time limitations. However, we found that even without using the Delphi technique, the treatment goals agreed on by the psoriasis specialists were almost the same as the consensuses reached by different nations. This suggests that the consensuses reached by Korea or by European countries could be applied to other nations in similar situations.

Only one question, about whether objectively moderate to severe psoriasis which is subjectively perceived mild psoriasis could be possible or not, showed a meaningful difference between Korean and European doctors14. In Korea, there is not enough time to assess patients' HRQoL issues in outpatient clinics because large numbers of patients have to be seen in a limited time, especially in tertiary referral hospitals. The DLQI is not commonly used either during initial visits or during routine follow-up appointments; hence, Korean doctors do not have a chance to hear patient complaints about HRQoL issues that are caused by chronic morbidities associated with psoriasis. Thus, the objective psoriasis severity parameters that are assessed by the doctors, including the PASI score and the BSA, have been the only parameters used to assess the severity of the disease in patients. Discussions about the importance of considering the HRQoL issues of psoriasis patients in Korea have taken place. It is desirable to develop a short questionnaire to assess HRQoL issues that could be completed within one minute and is presented in a format that is similar to the visual analog scale used for subjective pain assessment.

This study was limited because it was impossible to develop a consensus statement from the results of the conference. Given the small number of participants, all of the participants would have to show complete agreement to exceed the limit of consensus, which is set at 90%, and if one of the participants disagreed to a response to one of the questions8, we could not reach consensus. This limitation was another reason for not using the Delphi technique.

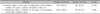

Fig. 1 presents a schematic diagram of a newly proposed Korean psoriasis treatment goal developed during this consensus conference, and we have modified the subjective measurement of severity by using HRQoL instead of the numeric DLQI. The development of a less time-consuming HRQoL assessment tool in the future that could be administered to patients with psoriasis could replace the HRQoL part of this diagram. We hope that this consensus conference represents the beginning of the development of patient-centered psoriasis treatment guidelines for Korean psoriasis patients.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Korean treatment goals for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, which were revised from the European consensus. An assessment tool for measuring health-related quality of life issues in Korean patients should be developed further. An objective cut-off value should be validated. PASI: psoriasis area and severity index, HRQoL: health-related quality of life. |

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by the AbbVie Korea Ltd. The sponsors supported the consensus conference only, and they had no roles in the collection, analysis, or in the interpretation of the data, or in the preparation and publication of the manuscript.

References

3. Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, Ashcroft DM;; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013; 133:377–385.

4. Hsu S, Papp KA, Lebwohl MG, Bagel J, Blauvelt A, Duffin KC, National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board, et al. Consensus guidelines for the management of plaque psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2012; 148:95–102.

5. Pathirana D, Nast A, Ormerod AD, Reytan N, Saiag P, Smith CH, et al. On the development of the European S3 guidelines on the systemic treatment of psoriasis vulgaris: structure and challenges. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010; 24:1458–1467.

6. Ohtsuki M, Terui T, Ozawa A, Morita A, Sano S, Takahashi H, et al. Japanese guidance for use of biologics for psoriasis (the 2013 version). J Dermatol. 2013; 40:683–695.

7. Smith CH, Anstey AV, Barker JN, Burden AD, Chalmers RJ, Chandler DA, Chair of Guideline Group, et al. British Association of Dermatologists' guidelines for biologic interventions for psoriasis 2009. Br J Dermatol. 2009; 161:987–1019.

8. Kragballe K, Gniadecki R, Mørk NJ, Rantanen T, Ståhle M. Implementing best practice in psoriasis: a Nordic expert group consensus. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014; 94:547–552.

9. Mrowietz U, Kragballe K, Reich K, Spuls P, Griffiths CE, Nast A, et al. Definition of treatment goals for moderate to severe psoriasis: a European consensus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2011; 303:1–10.

10. Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)--a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994; 19:210–216.

11. Finlay AY, Basra MK, Piguet V, Salek MS. Dermatology life quality index (DLQI): a paradigm shift to patient-centered outcomes. J Invest Dermatol. 2012; 132:2464–2465.

12. Gupta AK, Pandey SS, Pandey BL. Effectiveness of conventional drug therapy of plaque psoriasis in the context of consensus guidelines: a prospective observational study in 150 patients. Ann Dermatol. 2013; 25:156–162.

13. Lee YW, Park EJ, Kwon IH, Kim KH, Kim KJ. Impact of psoriasis on quality of life: relationship between clinical response to therapy and change in health-related quality of life. Ann Dermatol. 2010; 22:389–396.

14. Zweegers J, van den Reek JM, van de Kerkhof PC, Otero ME, Ossenkoppele PM, Njoo MD, et al. Comparing treatment goals for psoriasis with treatment decisions in daily practice: results from a prospective cohort of patients with psoriasis treated with biologics: BioCAPTURE. Br J Dermatol. 2014; 171:1091–1098.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download