Abstract

Background

The rapid development of information and communication technology has replaced traditional books by electronic versions. Most print dermatology journals have been replaced with electronic journals (e-journals), which are readily used by clinicians and medical students.

Objective

The objectives of this study were to determine whether e-readers are appropriate for reading dermatology journals, to conduct an attitude study of both medical personnel and students, and to find a way of improving e-book use in the field of dermatology.

Methods

All articles in the Korean Journal of Dermatology published from January 2010 to December 2010 were utilized in this study. Dermatology house officers, student trainees in their fourth year of medical school, and interns at Korea University Medical Center participated in the study. After reading the articles with Kindle 2, their impressions and evaluations were recorded using a questionnaire with a 5-point Likert scale.

Results

The results demonstrated that gray-scale e-readers might not be suitable for reading dermatology journals, especially for case reports compared to the original articles. Only three of the thirty-one respondents preferred e-readers to printed papers. The most common suggestions from respondents to encourage usage of e-books in the field of dermatology were the introduction of a color display, followed by the use of a touch screen system, a cheaper price, and ready-to-print capabilities.

The rapid development of information and communication technology (ICT) has changed how people read books1. Traditional books are being replaced by electronic versions, and various content-including magazine, newspaper, and academic journal content-has been published in digital form. The use of electronic books (e-books) started to increase in earnest after Internet use became widespread in the early 1990s2. The current generation of dedicated electronic readers (e-readers) has standardized around a new kind of display technology, called E ink, which comprises a stand-alone e-reader3. E ink has the merit of low power consumption and high contrast, and has a reflective, rather than a transmissive display, which makes it easier on the eyes when reading. This type of reader consumes less power than other similar devices; however, one of its disadvantages is that current technology limits it to only displaying text and pictures in shades of gray4.

The effects of the growth in the e-book market have been obvious in the field of medicine. The amount of variable digital medical resources has grown exponentially in the past decades. These allow for immediate and easy access to abundant and inexpensive information for both reference and medical education purposes4,5,6,7. The visual nature of dermatology is especially well utilized by digital image resources. Most print dermatology journals have been replaced with electronic journals (e-journals) and are readily used by clinicians and medical students8,9. However, academic use of handheld e-readers, such as the Amazon Kindle, is in its infancy, although these e-readers are rising in popularity for leisure reading purposes. How do these trends affect the reading of dermatology journals using e-readers? As mentioned above, current hand-held e-readers display text and pictures only in gray-scale, although they are convenient to use in many ways. The objectives of this study were to determine whether e-readers are appropriate for reading dermatology journals, to conduct an attitude study of both medical personnel and medical students, and to find a way of improving e-book use in the field of dermatology. To our knowledge, this is the first report in the literature to evaluate and discuss the academic use of e-readers with respect to dermatology.

All articles in the Korean Journal of Dermatology (KJD) published from January 2010 to December 2010 were utilized in this study. KJD is the official Korean journal of the Korean Dermatological Association, and was first published in 1960. It is published monthly, and is listed in KoreaMed, KOMCI, SCOPUS, and Google Scholar. Articles were analyzed according to their type, and the number of figures, photographs, and graphs they contained. Articles were classified into the following types: original articles, case reports (including short reports), and expert opinions. In the analysis, expert opinion articles were grouped with original articles for convenience of comparison.

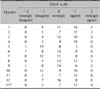

One of the authors (Ahn HH) read all the articles using Amazon Kindle 2. Kindle 2, which was launched in 2009, has a six-inch screen and sixteen levels of gray-scale. It introduces native Portable Document Format support after firmware update, and is estimated to hold about 1,500 non-illustrated books3. For each of the papers, the necessity of color for understanding was evaluated for photos, graphs, and the paper overall, using the color index (Table 1). Differences in understanding these aspects were compared between case reports and original articles.

Dermatology house officers, student trainees in their fourth year of medical school, and interns at Korea University Medical Center participated in the study. They were asked whether they had ever used e-readers before, and about their fields of interest in dermatology. The field of dermatology was classified into dermatopathology, allergology, immunology, hair, skin cancer, cosmetic dermatology, dermatosurgery, and others. Multiple choices were allowed. After reading the articles using Kindle, they were asked to respond to a 13-item questionnaire about their satisfaction and comprehension levels using a 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree and strongly disagree, with assigned scores of 2, 1, 0, -1, and -2, respectively; Table 2). In addition, they were asked about the proper size of the screen for reading, and an open-ended question was presented, which invited their suggestions to improve the use of e-readers for reading dermatology journals. Their answers were analyzed according to sex, age, position (medical personnel vs. students), number of postgraduate years (PGY), and experience of e-book use. Past experience of e-book use and fields of interest were also analyzed according to sex, age, position, and PGY.

Results were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 20.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). The number of figures, photos, and graphs were compared between case reports and original articles using Student's t-test. The color indexes of photos, graphs, and overall papers were compared between case reports and original articles using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. As for the survey participants, differences in experience of using e-readers and fields of interest according to sex and position were compared using Fisher's exact test. The Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test was used to identify trends according to PGY. Differences in questionnaire responses according to sex, position, and experience of using an e-reader were compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. The Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test was used to identify trends according to age.

A total of 231 articles were published in the KJD from January 2010 to December 2010. They were composed of 161 case reports, 64 original articles, and 6 expert opinions. The mean number of total pages was 3.9±0.86 for case reports and 7.4±1.55 for original articles (including expert opinions). The mean number of figures was 2.67±1.11 for case reports and 3.57±2.31 for original articles. The mean number of photos was 2.65±1.10 for case reports and 2.00±2.40 for original articles, and the number of graphs was 0.01±0.11 for case reports and 1.57±1.59 for original articles. The photos included clinical photos and photomicrographic images of histology, while the graphs were of diverse form, and included pie graphs, line graphs, and bar graphs.

One dermatologist read all the articles using Kindle and evaluated the color necessary for understanding according to the color index (Table 3). The photo color index (p=0.04) and total color index (p=0.16) were higher, while graph color index (p=0.21) was lower in case reports compared to original articles.

Thirty-one participants (16 dermatology house officers, 14 student trainees in their fourth year of medical school, and 1 intern) completed the questionnaire. Nineteen were men and twelve were women. The mean age was 28±2.6 (range 25~35) and mean PGY was 1.8±1.9 (range 0~5). Only ten participants had experience using e-readers, while the remaining twenty-one had never used one before. This difference was not related to sex, PGY, or position (p=0.70, p=0.50, and p=0.44, respectively). Their fields of interest were, in order of frequency, cosmetic dermatology (15), allergology (11), dermatopathology (6), dermatosurgery (5), hair (4), immunology (2), skin cancer (2), and others (2). Dermatology residents and the intern tended to be interested in dermatosurgery (p<0.05) and dermatopathology (p=0.02) compared to the students; students tended to be interested in cosmetic dermatology (p=0.02). Sex and PGY were not related to the field of interest.

Participants' responses to the questionnaire on the 5-point Likert scale (possible range of scores: -2 to +2) are shown in Table 4. Responses ranged from "difficult" to "not at all difficult" to the first three questions that asked about the difficulty of understanding the photos, graphs, and overall papers using a Kindle. Differences in responses regarding photos, graphs, and overall papers were not related to sex (p=1.00, p=0.14, p=0.54, respectively), age (p=0.32, p=0.93, p=0.17), position (p=0.74, p=0.57, p=0.91), or past experience of e-book use (p=0.72, p=0.06, p=0.13). Most of the respondents agreed that the advantage of E ink was that it is a reflective display, rather than a transmissive one (Question 4). However, only three participants preferred e-readers to printed papers (Question 5). The preference was not related to their sex (p=0.91), age (p=0.96), position (p=0.58), or past experience of use (p=0.11). For the question asking about the proper size of the screen to read the papers, most of the respondents preferred a larger size than the current six inches of the e-reader (Question 13). Men tended to prefer a larger screen than women (p=0.01). In response to the open-ended question inviting suggestions for increasing the use of e-readers for the reading of dermatology journals, the most common suggestion was the introduction of a color display, followed by the use of a touch screen system, a cheaper price, and ready-to-print capabilities (Table 5).

Image data are particularly important in the field of dermatology, as it is the branch of medicine dealing with the skin-an organ that is exposed to the outside and its diseases. Compared to other branches of medicine, most dermatologic literature contains a large number of photos. In this study, the average number of photos in a paper was more than two. All the articles in the form of case reports included more than one photo, while there were some original articles without any photos. Case reports contained more photos than original articles (p=0.01), though graphs were nearly exclusively included in original articles (p<0.01). The number of photos might depend on the topic of the paper. For example, case reports include a large number of photos because they aim to introduce the symptoms and diagnosis of an individual patient. The photos in dermatology are usually the major core content of the paper, and often consist of clinical photos of skin lesions and microscopic images of histology.

One of the practices that makes good use of the visual nature of dermatology is teledermatology10,11. Teledermatology refers to the study and practice of dermatology care using interactive audio, visual, and data communications from a distance12. Patients in remote geographic regions can access dermatological care by sending their skin photographs to dermatologists, saving time and reducing costs in the process13. Electronic learning (e-learning), a recent type of education using ICT, is also useful in the field of dermatology because of its visual nature. E-learning is a unifying term used to describe Internet-enabled learning or learning supported by the application of ICT5. There are growing numbers of online dermatologic resources, including variable image data14. They allow inexpensive and easy access to medical information, as traditional dermatologic texts and journals are rather expensive because of their heavy image content. E-learning resources are more likely to be updated and current, and facilitate interactivity and feedback between people6,15,16. E-learning has rapidly been adopted as a means of education and training in many universities and hospitals.

More recently, mobile smart devices such as smartphones, tablet personal computers and personal digital assistants are rapidly diffusing throughout society and changing people's digital reading behavior1. It is a great advantage for busy people to be able to access a massive information database anywhere and anytime just by carrying simple mobile devices17,18. E-readers are dedicated mobile devices for storing and reading digital content. People can find and read anything they want to read outside the office and the classroom. The current generation of e-readers has standardized around a type of display manufactured by the E Ink Corporation (Cambridge, MA, USA)3. The mechanism of E ink is likened to a flat sheet covered in ping-pong balls, with each ball having one black and one white hemisphere. The balls needed to show the black sides flip, and the rest leave their white side visible to display things on the sheet. The balls in an E ink display are roughly the circumference of human hair and controlled by electrical charges. E ink has incredibly low power consumption and high contrast, and reflects, rather than emits light from behind the screen, a feature that makes the eyes comfortable while reading, while allowing the device to use less power3. It has definite advantages over the more standard type of electronic display, such as the liquid crystal display (LCD) or organic light emitting diode (OLED). LCD is a thin, flat display device made up of color or monochrome pixels arrayed in front of a light source. It is non-emissive by itself, but requires a backlight for proper functioning, which classifies it as a transmissive display. Thus, it consumes more power and may cause eyestrain, which makes it more suitable for brief reading. In addition, it has poor readability in bright ambient light, such as outdoor light. The OLED display, another type of current display technology, has polymers that emit light when a current is passed through them in one direction. Unlike an LCD, the OLED display does not require a backlight, consuming less power than the LCD. However, the metallic cathode in an OLED acts as a mirror, leading to poor readability in direct sunlight. There are, however, also some disadvantages to E ink. One of them is its gray-scale display, as it is composed of black and white spheres. It may be a critical defect for color images of photos and graphs, although not a significant problem for text reading19.

The results of the study demonstrated that gray-scale e-readers might not be suitable for reading dermatology journals, especially for reading case reports, which usually include many photographs. The total color index was higher than 1 for both types of papers, which means that there were some problems in overall comprehension in gray-scale. The total color index was higher in case reports than in original articles (1.46 vs. 1.2) although the difference was not statistically significant. The lack of color was a critical limitation for clinical photos or microscopy photos of histology. Quite a few case reports were possibly misleading and their main message may not have been apparent. Against our expectations, the participants appeared to be slow to use e-readers; only ten out of thirty-one had used one before. There were a considerable number of complaints about reading dermatology journals using Kindle. Nine out of thirty-one participants complained about difficulty understanding photos giving low comprehension scores, five complained about reading graphs, and three about reading overall papers. It was surprising that only three of the respondents preferred e-readers than printed papers, nineteen preferred printed papers, and ten were neutral. As expected, the most common suggestion for increasing the use of e-readers was a color display, followed by a touch screen. The latter suggestion may be influenced by the rapid diffusion of touch screen smartphones. Some of the newest e-readers already support this system. Meanwhile, e-readers with color E ink displays are not yet available, although development is ongoing3. A limitation of our study is that more than half of the questionnaire respondents were first-time users of e-readers. They may have been more accustomed to reading printed papers and not so familiar with the new device, which could have had a negative effect on their satisfaction. The small sample size of the respondents is also a limitation.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that current e-readers might not be suitable for reading dermatology journals. The e-reader's gray-scale E ink display possibly does not display color images well, obscuring the main message of the papers. However, e-reader users are increasing and these devices have many advantages, such as portability, Internet access, and a massive amount of material available at low cost. Thus, they may be more useful in selected situations, depending on the type and topic of the papers; for example, e-readers are more appropriate for reading original articles, and other kinds of papers in which color photos are not essential, than for reading case reports. Future development of color E ink would expand the application of e-readers in the field of dermatology.

Figures and Tables

Table 3

Total numbers and color indexes of photos and graphs included in case reports and original articles

References

1. Lee S. An integrated adoption model for e-books in a mobile environment: Evidence from South Korea. Telemat Inform. 2013; 30:165–176.

2. Vasileiou M, Hartley R, Rowley J. An overview of the e-book marketplace. Online Inform Rev. 2009; 33:173–192.

3. Griffey J. Electronic book readers. Libr Technol Rep. 2010; 46:8–19.

4. Folb BL, Wessel CB, Czechowski LJ. Clinical and academic use of electronic and print books: the Health Sciences Library System e-book study at the University of Pittsburgh. J Med Libr Assoc. 2011; 99:218–228.

5. Fraser L, Gunasekaran S, Mistry D, Ward VM. Current use of and attitudes to e-learning in otolaryngology: questionnaire survey of UK otolaryngology trainees. J Laryngol Otol. 2011; 125:338–342.

6. Morton DA, Foreman KB, Goede PA, Bezzant JL, Albertine KH. TK3 eBook software to author, distribute, and use electronic course content for medical education. Adv Physiol Educ. 2007; 31:55–61.

7. Raynor M, Iggulden H. Online anatomy and physiology: piloting the use of an anatomy and physiology e-book-VLE hybrid in pre-registration and post-qualifying nursing programmes at the University of Salford. Health Info Libr J. 2008; 25:98–105.

8. De Groote SL, Dorsch JL. Measuring use patterns of online journals and databases. J Med Libr Assoc. 2003; 91:231–240.

9. De Groote SL, Shultz M, Doranski M. Online journals' impact on the citation patterns of medical faculty. J Med Libr Assoc. 2005; 93:223–228.

10. Kanthraj GR. Newer insights in teledermatology practice. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011; 77:276–287.

11. Ahn HH, Kim JE, Ko NY, Seo SH, Kim SN, Kye YC. Videoconferencing journal club for dermatology residency training: an attitude study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007; 87:397–400.

12. Perednia DA, Brown NA. Teledermatology: one application of telemedicine. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1995; 83:42–47.

13. Kanthraj GR. Classification and design of teledermatology practice: what dermatoses? Which technology to apply? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009; 23:865–875.

14. Hanson AH, Krause LK, Simmons RN, Ellis JI, Gamble RG, Jensen JD, et al. Dermatology education and the Internet: traditional and cutting-edge resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011; 65:836–842.

15. Krejci-Papa NC, Bittorf A, Diepgen T, Huntley A. Dermatology on the Internet. A source of clinical and scientific information. J Dermatol Sci. 1996; 13:1–4.

16. Wainwright BD. Clinically relevant dermatology resources and the Internet: An introductory guide for practicing physicians. Dermatol Online J. 1999; 5:8.

17. Fischer S, Stewart TE, Mehta S, Wax R, Lapinsky SE. Handheld computing in medicine. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003; 10:139–149.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download