Abstract

Background

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is characterized by itching and eczema-like skin lesions, and its symptoms alleviate with age. Recently, the prevalence of AD has increased among adolescents and adults. The increasing prevalence of AD seems to be related to westernized lifestyles and dietary patterns.

Objective

The aim of this study was to evaluate the dietary patterns and nutrient intake of patients with AD.

Methods

The study population consisted of 50 children with AD who visited the Department of Dermatology at Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital, Seoul, Korea from May 2008 to May 2009. Physical condition and calorie intake were evaluated using the Eczema Area and Severity Index score and Food Record Questionnaire completed by the subjects, and the data were analyzed using the Nutritional Assessment Program Can-pro 3.0 (The Korean Nutrition Society, 2005) program to determine the gap between the actual ingestion and average requirements of 3 major nutrients (i.e. carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids), vitamins (i.e. A, B, C, and E), niacin, folic acid, calcium, iron, phosphorus, and zinc in all subjects.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common, chronic relapsing inflammatory skin disease that especially affects children and adolescents1. Because parents tend to restrict the dietary intake of their AD-afflicted children, young AD patients have dietary patterns that differ from those of other children. Parents would rather have their children eat vegetables and fruits than dairy products, meat, and fish because of suspected food allergies or their own hypersensitivities2. Moreover, some authors have reported that avoiding food allergens helps prevent allergic diseases3,4. However, if this type of diet continues for a long time, growth retardation (e.g. weight loss and suppression of skeletal maturation) could occur in the patients with allergic diseases5. Growth retardation was found to be related to digestive disorders and inappropriate dietary restrictions in AD patients. In addition, growth retardation in AD patients often occurs in proportion to the severity of AD6.

In this study, the authors surveyed the dietary patterns and nutritional status of Korean AD patients using a computerized assessment program. We also analyzed the relationship between the severity of AD and intake of various nutrients.

This study involved 50 children (28 boys [56%] and 22 girls [44%]) with AD who visited the Department of Dermatology at Hallym University Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital in Seoul, Korea from May 2008 to May 2009 (AD group). This study was approved by the institutional review board of Hallym University Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital (IRB 2013-08-68), and informed consent was obtained. This AD group consisted of AD patients with Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores of >5 and ≤10 (moderate AD group) and of ≤5 (mild AD group). The patients were aged between 6 and 18 years. All patients fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of Hanifin and Rajka1. The exclusion criteria included other chronic diseases (asthma, diabetes, and congenital disorders), severe AD (EASI score>10) and a previous history of oral or topical steroid treatment.

The mean age of the subjects was 8.24±5.24 years. Their mean duration of disease was 4.26±3.08 years, and 18 patients had a family history of AD. The low proportion of patients with a family history could be attributed to the poor memory of family history, limited access to medical service for diagnosis in the past, or late westernization in Korea.

The severity of AD was assessed by a trained dermatologist using the EASI score. We chose the EASI score as an index of disease severity because the AD in most of our subjects was classified as mild, per Rajka and Langeland's scoring system. Obesity of the patients was determined by referring to the Korean standard growth chart (established in 2007), and the patients were classified into 4 grades accordingly.

Physical conditions and energy intake were evaluated using the Food Record Questionnaire and the results were analyzed using the Nutritional Assessment Program Canpro 3.0 (The Korean Nutrition Society, 2005, Seoul, Korea). We analyzed the data from the patients' diaries regarding several nutrients, namely carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, and other micronutrients, such as vitamins, and evaluated the differences in the levels of nutrients between the AD and control groups. Data regarding normal nutritional values for Korean children were collected from the Dietary Reference Intakes for Koreans recommended by The Korean Nutrition Society, 2005 (control group). The program we used is similar to Mosby's NutriTrac Nutrition Analysis Software (Mosby, 2005, St. Louis, MO, USA). We collected information from all subjects regarding dietary intake for 3 days (2 random weekdays and 1 day on the weekend), using the food record method, including food restrictions. Data were collected 5 times per day: breakfast, lunch, dinner, morning snack, and afternoon snack. The data included food name, weight of the main ingredients, and amount of nutrient intake. In cases where the intake amounts were unclear, we estimated the amounts by calculating the proportion of the basic required amount (e.g. a half bowl of rice is equal to 50%). We also determined the intake of 3 macronutrients (carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids) of all subjects. From these data, we analyzed the dietary intake with the reference of the average requirements of the 3 major nutrients (carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids), vitamins (A, B, C, E, niacin, and folic acid), and electrolytes (calcium, iron, phosphorus, and zinc) using the Nutritional Assessment Program Can-pro 3.0. The average body weight and energy intake were calculated using the nutrient intake information from questionnaires on height and body weight. Then, we compared the height and weight of each subject with the normal value for each subject's age, summed the differences and calculated the average of the 2 groups: with sufficient nutrient intake and insufficient. We selected 2 nutrients for grouping in this experiment (i.e. nutrients patients usually consumed the least). We compared height and weight between subjects with insufficient nutrient intake or those with sufficient nutrient intake and children with average height and weight for their age.

This study aimed to determine whether the subjects preferred instant foods to homemade foods and liked confectioneries, including chocolate, to fruit as a snack, and whether they were breast fed during infancy. We calculated the energy intake of all subjects by the food diary method, using dietary reference intakes for Koreans. The correlation between the severity of AD and nutritional status was determined in the mild and moderate AD groups.

Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS 12.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Student's t-test was performed to compare the differences between the mild and moderate AD groups. Results were analyzed using the Nutritional Assessment Program CAN pro 3.0 (The Korean Nutrition Society, 2005). The number of deficient nutrients was compared between the moderate and mild AD groups by the Mann-Whitney test. The correlation between the severity of AD and dietary status was determined by logistic regression analysis. Demographic characteristics and clinical data were presented. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The mean EASI score was 5.11±2.06 for all subjects, 3.23±0.75 for the subjects in the mild AD group (n=20), and 6.30±1.76 for those in the moderate AD group (n=30). Of the subjects, 1 (2%) was underweight, 31 (62%) had normal weight, 14 (28%) were overweight, and 4 (8%) were obese.

Energy intake was insufficient in 11 subjects (22%), adequate in 24 subjects (48%), and excessive in 15 subjects (30%; Table 1). Protein intake was 18.02% (recommended dietary allowance [RDA], 7%~20%), carbohydrate intake 67.7% (RDA, 55%~70%), and lipid intake 14.24% (RDA 15%~30%), as per the Nutritional Assessment Program Can-pro 3.0 (Table 2). The AD group consumed less folic acid-rich foods than the control group. Thirty-one subjects (62%) were deficient in folic acid and 21 subjects (42%) in iron. Some patients were also deficient in other nutrients: vitamin C (n=17, 34%), calcium (n=15, 30%), niacin (n =14, 28%), and vitamin A (n=12, 24%). AD patients showed marked deficiency in phosphorus, vitamin B, vitamin E, and zinc, as compared to other nutrients (Table 3).

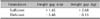

Folic acid and iron, which were the least consumed nutrients, were chosen for further analysis in this study. The subjects who consumed sufficient folic acid and iron were, on average, 1.45 cm taller and 2.68 kg heavier than normal, while those who consumed inadequate amounts of these nutrients was 5.48 cm shorter and 0.13 kg lighter than normal. However, the difference was not statistically significant (Table 4).

Eight subjects were under restriction for the following foods: fast food (n=5), egg (n=3), and cow's milk (n=2). None of the subjects showed any food allergy.

More patients preferred instant foods (n=34, 68%) to homemade foods (n=16, 32%). Of the 50 subjects, 17 were breast fed during infancy. Further, 27 subjects (54%) liked fruits; 31 subjects (62%) liked confectionaries, such as chocolate, snacks, and candies; and 8 subjects (16%) had both for snacks.

The highest EASI score among the patients was 10. There were no significant differences in nutrient state (weak, normal, overweight, obese), sex, or age between the mild and moderate AD groups. Lipid intake was lower and carbohydrate intake was higher in the moderate AD group than in the mild AD group; however, protein intake was similar in both groups. There was no significant difference in nutrient intake between the 2 groups.

The number of deficient nutrients was assessed in the 2 groups. The patients in the moderate AD group were deficient in a mean of 3.57±2.54 nutrients, and those in the mild group, in a mean of 1.70±1.42 nutrients (p=0.007). Poor nutrient intake was more common in the moderate AD group than in the mild AD group. Of the 17 patients who were breast fed, 15 belonged to the mild AD group (Table 5, 6). The average duration of breast-feeding was 11 months. There was no significant difference in the duration of breast-feeding between the 2 groups.

AD is characterized by itching, eczema-like skin lesions1. Some studies have reported that AD patients show deficiencies in specific nutrients and that their symptoms can be reduced by proper nutrient supplementation7,8. Husemoen et al.9 found that patients with low calorie intake show very severe clinical symptoms and that folic acid deficiency correlates with the occurrence of AD in male children9. In our study, it was found that AD patients were deficient mainly in folic acid and iron contained in vegetables, peanuts, fish, and soybeans. Chatzi et al.10 stated that skin lesions of AD patients significantly improved after the consumption of folate- and iron-rich vegetable such as tomatoes, eggplants, cucumbers, and peas10. Folate is essential for the remethylation of homocysteine, and elevated levels of homocysteine or of some of its metabolites appear to exert a number of diverse effects on immune function11. On the basis of these findings, we inferred that poor intake of folate status may be related to the aggravation of AD symptoms because of an altered Th1/Th2 balance resulting from the inhibition of remethylation of homocysteine. In addition, folate is important in cell proliferation, especially of cells that have high turnover rates, as in the cases of exfoliative dermatitis, psoriasis, or AD12,13.

The relationship between AD and iron deficiency is not well determined. A previous study on the deficiency of trace metals in AD patients showed a significant reduction in serum ferritin and iron levels in AD patients14, implying a depletion of body iron stores. Given the frequent iron loss in malabsorption associated with AD or exfoliative dermatitis, it is possible that AD itself causes iron loss. In addition, pruritus is a common symptom in iron deficiency anemia (IDA) that causes an AD patient to frequently scratch the skin and consequently aggravate the skin lesion. Therefore, AD patients with IDA have severe pruritus, and the vicious cycle continues. Iron could be related to the clinical progression of AD. Although we did not measure the serum iron and folate levels, we presume that they would be low owing to insufficient intake. Both nutrients have a short in vivo half-life and their dietary intake is necessary; moreover, folate and iron supplementation may have helped improve symptoms in some patients. Previous studies on the nutritional status of Korean children and adults showed that the calcium, iron, and folate intakes of the subjects were lower than the recommended levels15,16. In addition, Ahn et al.17, who studies the nutritional intake pattern of 78 allergic patients with AD or asthma, suggested that AD patients have lower iron, calcium, vitamin, and folate intake than normal subjects17. It is presumed that folate deficiency is severe in AD patients. Furthermore, vegetarians are usually deficient in iron and vitamin B12, as a result of their restriction of meat ingestion. The dietary habits of Koreans and other Asians that have a diet dominated by grains rather than meat could be related to the deficiency of iron and vitamin B1218. Vitamin B12 deficiency may lead to folate deficiency19, in turn leading to the aggravation of dermatitis. Controversies exist regarding the correlation between AD and fruit consumption. Barth et al.8 pointed out that AD patients consume a significantly small number of fruits and that a decrease in antioxidant-rich fruit aggravates the AD symptoms8. However, some reports recommend a low intake of fruits such as mandarins and oranges in AD patients because some ingredients in these fruits cause topical itching. In our study, AD patients liked instant foods, and only 54% of the patients preferred fruits to instant foods-they probably believed that fruits are better than instant foods at alleviating AD symptoms. In another study, AD patients preferred instant or fast foods, which might contain allergens20. However, in our study, there was no significant difference in fruit consumption between the moderate and mild AD groups.

Other factors, such as corticosteroids, could influence the progression of AD patients. However, in our study, only the subjects who did not receive steroid therapy were recruited. Patel et al.21 showed that corticosteroid therapy does not suppress AD progression. Food allergies may also aggravate AD22; none of our subjects had any food allergy. However, 8 subjects were under food restrictions imposed by their parents, only because they were concerned about their child's AD and not because of any definitive history of AD aggravation caused by specific foods.

The Nutritional Assessment Program Can-pro 3.0 was developed by The Korean Nutrition Society in 200523. This program is based on the nutrient data from 17 studies in the literature23. When the diet was input into the Can-pro program, nutrients contained in the diet can be identified including proteins, fats, carbohydrates, calcium, phosphorus, iron, sodium, potassium, β-carotene, retinol, vitamin A, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, vitamin B6, niacin, vitamin C, vitamin E, zinc, folate, and cholesterol23. In the previous study, the 2007 Korean Nutrition and Health Examination Survey findings were reanalyzed using Can-pro 3.0; Can-pro 3.0 is a useful tool for evaluating people's nutrient status23.

In conclusion, this study showed that AD patients with poor oral nutrient intake have more severe symptoms than the other groups. Participants were most frequently deficient in folate and iron, and an analysis of food preference also indicated deficiencies of vitamin A, vitamin C, calcium, and niacin among the patients. These nutrients are found in vegetables, peanuts, and fish and may cause allergic reactions. None of our subjects were restricted from consuming these foods, but misunderstanding of different foods might lead to an insufficient intake of these foods, resulting in deficiencies of the aforementioned nutrients. Proper food allergy tests can help avoid such food restrictions. Further, 34% of the patients who were breast-fed had mild AD symptoms, implying that breast-feeding influences the severity of AD. Many studies suggested that breast-feeding is a useful method for preventing or delaying AD symptoms24,25,26,27,28. AD patients tend to consume fewer essential nutrients than healthy subjects, and the resultant lack of nutrients is closely related to the severity of AD. It is necessary for AD patients to maintain adequate nutrition through the intake of a variety of foods, such as vegetables and fruits. In addition, professional guidance is essential for eliminating foods that have been proven to elicit adverse reactions in oral provocation tests.

This study has some limitations. We excluded severe AD patients treated with steroids or other medications, which might influence the growth of AD patients. Blood tests for the evaluation of objective nutritional deficiency or assessment of clinical signs of nutritional deficiency, e.g. anemia related to iron deficiency, will be required in future research. The cause and effect relationship between the deficiency of some nutrients and the severity of AD is still unclear. Further studies are needed to determine whether the supplementation of nutrients can help alleviate AD symptoms in AD patients with nutrient deficiency.

Figures and Tables

Table 4

Height and weight gap in folate and iron sufficients and deficient groups comparing to normal levels

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2011-0013003 and NRF-2012R1A1B3002196) and Hallym University Research Fund.

References

1. Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol (Stockh). 1980; 92:Suppl. 44–47.

2. Williams HC, Burney PG, Pembroke AC, Hay RJ. Validation of the U.K. diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis in a population setting. U.K. Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis Working Party. Br J Dermatol. 1996; 135:12–17.

3. Williams HC, Wuthrich B. The natural history of atopic dermatitis. In : Williams HC, editor. Atopic dermatitis: the epidemiology, causes, and prevention of atopic eczema. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press;2000. p. 41–59.

4. Tanaka T, Kouda K, Kotani M, Takeuchi A, Tabei T, Masamoto Y, et al. Vegetarian diet ameliorates symptoms of atopic dermatitis through reduction of the number of peripheral eosinophils and of PGE2 synthesis by monocytes. J Physiol Anthropol Appl Human Sci. 2001; 20:353–361.

5. Cohen MB, Weller RR, Cohen S. Anthropometry in children: progress in allergic children as shown by increments in height, weight and maturity. Am J Dis Child. 1940; 60:1058–1066.

6. Palit A, Handa S, Bhalla AK, Kumar B. A mixed longitudinal study of physical growth in children with atopic dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007; 73:171–175.

7. Rackett SC, Rothe MJ, Grant-Kels JM. Diet and dermatology. The role of dietary manipulation in the prevention and treatment of cutaneous disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993; 29:447–461.

8. Barth GA, Weigl L, Boeing H, Disch R, Borelli S. Food intake of patients with atopic dermatitis. Eur J Dermatol. 2001; 11:199–202.

9. Husemoen LL, Toft U, Fenger M, Jørgensen T, Johansen N, Linneberg A. The association between atopy and factors influencing folate metabolism: is low folate status causally related to the development of atopy? Int J Epidemiol. 2006; 35:954–961.

10. Chatzi L, Torrent M, Romieu I, Garcia-Esteban R, Ferrer C, Vioque J, et al. Diet, wheeze, and atopy in school children in Menorca, Spain. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2007; 18:480–485.

11. Dawson H, Collins G, Pyle R, Deep-Dixit V, Taub DD. The immunoregulatory effects of homocysteine and its intermediates on T-lymphocyte function. Mech Ageing Dev. 2004; 125:107–110.

12. Malerba M, Gisondi P, Radaeli A, Sala R, Calzavara Pinton PG, Girolomoni G. Plasma homocysteine and folate levels in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2006; 155:1165–1169.

13. Puustjärvi T, Blomster H, Kontkanen M, Punnonen K, Teräsvirta M. Plasma and aqueous humour levels of homocysteine in exfoliation syndrome. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004; 242:749–754.

14. David TJ, Wells FE, Sharpe TC, Gibbs AC, Devlin J. Serum levels of trace metals in children with atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 1990; 122:485–489.

15. Kim Y, Kim HA, Kim JH, Kim Y, Lim Y. Dietary intake based on physical activity level in Korean elementary school students. Nutr Res Pract. 2010; 4:317–322.

16. Lee HS, Kim BE, Cho MS, Kim WY. A study on nutrient intake, anthropometric data and serum profiles among high school students residing in Seoul. Korean J Community Nutr. 2004; 9:589–596.

17. Ahn HS, Lee SM, Lee MY, Choung JT. A study of the dietary intakes and causative foods in allergic children. Pediatr Allergy Respir Dis. 1999; 9:79–92.

18. Solvoll K, Soyland E, Sandstad B, Drevon CA. Dietary habits among patients with atopic dermatitis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000; 54:93–97.

19. Varela-Moreiras G, Murphy MM, Scott JM. Cobalamin, folic acid, and homocysteine. Nutr Rev. 2009; 67:Suppl 1. S69–S72.

20. McNally NJ, Phillips DR, Williams HC. The problem of atopic eczema: aetiological clues from the environment and lifestyles. Soc Sci Med. 1998; 46:729–741.

21. Patel L, Clayton PE, Jenney ME, Ferguson JE, David TJ. Adult height in patients with childhood onset atopic dermatitis. Arch Dis Child. 1997; 76:505–508.

22. Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Food hypersensitivity and atopic dermatitis: Pathophysiology, epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999; 104:S114–S122.

23. Shim YJ, Paik HY. Reanalysis of 2007 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2007 KNHANES) results by CAN-Pro 3.0 Nutrient Database. Korean J Nutr. 2009; 42:577–595.

24. Sicherer SH, Burks AW. Maternal and infant diets for prevention of allergic diseases: understanding menu changes in 2008. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008; 122:29–33.

25. Greer FR, Sicherer SH, Burks AW. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Allergy and Immunology. Effects of early nutritional interventions on the development of atopic disease in infants and children: the role of maternal dietary restriction, breastfeeding, timing of introduction of complementary foods, and hydrolyzed formulas. Pediatrics. 2008; 121:183–191.

26. Muraro A, Dreborg S, Halken S, Høst A, Niggemann B, Aalberse R, et al. Dietary prevention of allergic diseases in infants and small children. Part III: Critical review of published peer-reviewed observational and interventional studies and final recommendations. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2004; 15:291–307.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download