Abstract

Background

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is an immune complex-mediated disease predominantly characterized by the deposition of circulating immune complexes containing immunoglobulin A (IgA) on the walls of small vessels. Although the pathogenesis of HSP is not yet fully understood, some researchers proposed that B-cell activation might play a critical role in the development of this disease.

Objective

To investigate the serum levels of visfatin (pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor), B-cell-activating factor (BAFF), and CXCL13, and to analyze their association with disease severity.

Methods

The serum levels of visfatin, BAFF, and CXCL13 were measured by using a double-antibody sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in 43 patients with HSP and 45 controls. The serum levels of IgA anticardiolipin antibodies (ACA) were detected by using a double-antigen sandwich ELISA.

Results

Levels of visfatin but not BAFF and CXCL13 were significantly elevated in the sera of patients with HSP in the acute stage, and restored to normal levels in the convalescent stage. Furthermore, serum levels of visfatin were significantly higher in patients with HSP having renal involvement than in those without renal involvement. Serum levels of visfatin were correlated with the severity of HSP and serum concentration of ACA-IgA.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is a small-vessel vasculitis that is known as an immunoglobulin (Ig) A (IgA)-related immune complex-mediated disease1. Although the pathogenesis of HSP is not yet fully understood, some researchers proposed that B-cell activation might play a critical role in the development of this disease. A previous study reported that after T-cell depletion, B-cell-enriched fractions from patients with HSP maintained the overexpression of spontaneous IgG and IgA synthesis2. On the other hand, it has been recognized that depletion of mature B-lymphocytes by anti-CD20 (B-lymphocytes antigen) antibody is beneficial in the treatment of HSP3.

Visfatin, also known as pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor, is a transforming growth factor-β superfamily cytokine involved in tissue homeostasis, differentiation, remodeling, and repair4. It was identified as an adipokine secreted from human adipocytes and mouse 3T2-L1 adipocytes, and is synergized with interleukin-7 and stem cell factors to stimulate early-stage B-cell formation5,6. Moreover, visfatin is strongly upregulated in pathogenic or disease states such as acute injury, tissue hypoxia, inflammation, and oxidative stress7. Some studies have identified that the expression of visfatin is higher in a variety of chronic inflammatory diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)8,9.

B-cell-activating factor (BAFF), known as a B-lymphocyte stimulator, is a member of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily. It is produced mainly by myeloid cells (neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, and myeloid-derived dendritic cells)10. An environment of excess BAFF promotes the survival and maturation of autoreactive B-cells in order to break immune self-tolerance11. Experimental evidence has shown that BAFF-overexpressing transgenic mice exhibit B-cell hyperplasia and hypergammaglobulinemia, and develop autoimmune disease with manifestations that are similar to those in SLE12.

In addition, the chemokine CXCL13, also called B-cell-attracting chemokine 1, guides B-cells to follicles in secondary lymphoid organs, and is secreted by monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells11. It has an important role in the formation and maintenance of B-cells. Moreover, it has been reported that CXCL13 is a key molecule involved in B-cell activation in autoimmune myasthenia gravis13.

To summarize, visfatin, BAFF, and CXCL13 are important factors in the progression of B-cell activation. However, the roles of these factors in common types of cutaneous vasculitis, such as HSP and urticarial vasculitis (UV), are completely unknown. Therefore, investigating these factors and their correlations may be beneficial in further understanding the pathogenesis of HSP. It has been reported that some IgA autoantibodies, such as IgA anticardiolipin antibodies (ACA), are closely associated with the pathogenesis of HSP14. In this study, we also analyzed the potential relations of serum levels of visfatin, BAFF, and CXCL13 with disease severity and the production of these IgA autoantibodies in patients with HSP.

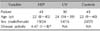

Forty-three patients with HSP (19 men and 24 women) who met the diagnostic criteria for HSP15, 30 patients with UV16, together with 45 age- and sex-matched controls, were enrolled in this study. Detailed history and complete physical examination were obtained from all patients (patient and control demographics, together with detailed clinical information, are provided in Table 1, 2). The activity and severity of HSP were assessed by using a clinical scoring system according to our previous report17. In 16 patients with HSP who were treated with oral antihistamines and vitamin C, we collected the sera in the acute stage18 and the convalescent stage, respectively19. All sera were stored at -80℃ until use.

The serum levels of visfatin, BAFF, CXCL13, and ACA-IgA were quantitated by using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

All results are expressed as mean±standard deviation. The differences in serum levels of visfatin, BAFF, and CXCL13 between patients with HSP, patients with UV, and the control group were determined according to the Mann-Whitney U-test. The serum levels of visfatin, BAFF, and CXCL13 in patients with HSP were compared between the acute stage and the convalescent stage by using the Wilcoxon signed ranks test. Correlation coefficients were obtained by using the Spearman test. SPSS Statistics ver. 17.0. (SPSS Inc., Chengdu, China) was used for statistical analyses. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

We first investigated the serum levels of visfatin in patients with HSP. As shown in Fig. 1A, we found that serum levels of visfatin were significantly elevated in patients with HSP in the acute stage (48.06±33.98 ng/ml) but not in patients with UV (24.73±14.77 ng/ml), when compared with those in healthy controls (26.92±19.01 ng/ml). In contrast, no marked changes were observed in the levels of BAFF and CXCL13 (Fig. 1B, C).

In 16 patients with HSP, we measured the serum levels of visfatin in both the acute stage and the convalescent stage. As Fig. 1D shows, the serum levels of visfatin were significantly higher in the acute stage than in the convalescent stage.

Furthermore, we investigated the relation of serum levels of visfatin in patients with HSP having different clinical manifestations. As Fig. 2 shows, the serum levels of visfatin were significantly higher in patients with HSP having renal involvement (59.78±37.04 ng/ml) than in those without renal involvement (36.78±25.98 ng/ml). However, there was no significant difference between patients with HSP with or without arthritis, abdominal pain, and upper respiratory tract infection (data not shown).

A correlation analysis was performed to investigate the relation of serum levels of visfatin, BAFF, or CXCL13 with disease severity of patients with HSP. As shown in Fig. 3A, there was a significant positive correlation between serum levels of visfatin and the overall clinical score. In addition, a similar correlation was also seen between the serum levels of visfatin and ACA-IgA (Fig. 3B).

In this study, we demonstrated for the first time that the serum levels of visfatin were elevated in the acute stage of HSP and restored to normal levels in the convalescent stage. Furthermore, we found that the serum levels of visfatin were correlated with the severity of the disease. In addition, we also investigated the potential role of serum levels of visfatin with different clinical manifestations in patients with HSP. Our data showed that the serum levels of visfatin were significantly higher in patients with HSP having renal involvement than in those without renal involvement. These findings suggest that visfatin may play a role in the pathogenesis of HSP. Visfatin may be one of the markers for evaluating disease severity in patients with HSP.

We also noticed that the serum levels of visfatin of patients with UV were not different compared with that of the control subjects. The reason for this result might be that HSP at least partly differs from UV in clinical manifestations and pathological changes. UV causes edema formation in the skin, whereas HSP manifests as purpura. In addition, patients with HSP have more systemic involvement than patients with UV. Furthermore, HSP is a much more serious disease than UV because it causes red blood cell extravasation and leukocyte diffusion20.

In addition, a few patients with HSP in this study showed increasing levels of visfatin during the convalescent stage. It is possible that some other potential or unknown factors, such as inflammation, injury in other tissues of the body, and disease recurrence, influenced the serum levels of visfatin although the clinical manifestations and laboratory findings of the patients returned to normal.

Visfatin is mainly expressed by cardiomyocytes, macrophages, endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, and adipocytes7. However, it is strongly upregulated in the presence of acute injury, tissue hypoxia, inflammation, and oxidative stress7. Several studies have shown that serum levels of visfatin are elevated in patients with cardiovascular diseases. As is well known, endothelial damage is an important event in the development of HSP; therefore, we supposed that visfatin might act as an acute-phase modifier in the inflammatory response to vascular injury, especially endothelial damage. Chung et al.9 suggested that the increased expression of visfatin in patients with systemic sclerosis, SLE, and dermatomyositis is associated with the upregulation of CCL2 (monocyte chemotactic protein-1, MCP-1). We presumed that some different cytokines and signaling pathways that interact with visfatin might be involved in the inflammatory process of HSP.

As described above, visfatin can induce early-stage B-cell formation. A recent study also indicated that serum levels of visfatin are related to the number of B-cells and decreased significantly after B-cell depletion in patients with rheumatoid arthritis21. These data suggest that visfatin may have an indirect effect on the induction of B-cell functions such as autoantibody production. In this study, we surmised that the serum concentration of visfatin is correlated with the concentration of ACA-IgA in patients with HSP. However, further research is still needed to determine whether elevated serum visfatin contributes to IgA autoantibody production in the pathogenesis of HSP.

This study provides the first observations on the changes of serum levels of visfatin and the relations of visfatin with disease severity, renal involvement, and IgA autoantibody production in patients with HSP. We suggest that visfatin may have a role in the pathogenesis of HSP. Further research should be directed toward an improved understanding of the pathobiology of visfatin and the therapeutic potential of targeting visfatin in HSP.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1The serum levels of visfatin, B-cell-activating factor (BAFF), and CXCL13 were determined by using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Sera were obtained from 43 patients with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) in the acute stage, 30 patients with urticarial vasculitis (UV), and 45 control subjects. The serum levels of visfatin (A) but not BAFF (B) and CXCL13 (C) in patients with HSP were significantly higher than those in control subjects. p-values are based on the results of the Mann-Whitney U-test. Wilcoxon signed ranks test for paired data showed that the serum levels of visfatin (D) of 16 patients with HSP in the acute stage were significantly higher than those in the convalescent stage. |

| Fig. 2The serum levels of visfatin in patients with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) having renal involvement (HSP1) or without (HSP2) renal involvement were determined by using ELISA. p-values are based on the results of the Mann-Whitney U-test. |

| Fig. 3Positive correlations were found between serum levels of visfatin and overall clinical scores (A), and between serum levels of visfatin and the concentrations of immunoglobulin A (IgA) anticardiolipin antibodies (ACA) (B) in 33 patients with Henoch-Schönlein purpura in the acute stage, by using the Spearman test. |

Table 1

Cohort demographics

Values are presented as number or median (range). HSP: Henoch-Schönlein purpura, UV: urticarial vasculitis, NA: not applicable. *Disease activity in HSP patients was assessed according to our previous reported method16.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of China (81101198).

References

1. Linskey KR, Kroshinsky D, Mihm MC Jr, Hoang MP. Immunoglobulin-A--associated small-vessel vasculitis: a 10-year experience at the Massachusetts General Hospital. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012; 66:813–822.

2. Beale MG, Nash GS, Bertovich MJ, MacDermott RP. Similar disturbances in B cell activity and regulatory T cell function in Henoch-Schönlein purpura and systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 1982; 128:486–491.

3. Donnithorne KJ, Atkinson TP, Hinze CH, Nogueira JB, Saeed SA, Askenazi DJ, et al. Rituximab therapy for severe refractory chronic Henoch-Schönlein purpura. J Pediatr. 2009; 155:136–139.

4. Böttner M, Laaff M, Schechinger B, Rappold G, Unsicker K, Suter-Crazzolara C. Characterization of the rat, mouse, and human genes of growth/differentiation factor-15/macrophage inhibiting cytokine-1 (GDF-15/MIC-1). Gene. 1999; 237:105–111.

5. Ding Q, Mracek T, Gonzalez-Muniesa P, Kos K, Wilding J, Trayhurn P, et al. Identification of macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 in adipose tissue and its secretion as an adipokine by human adipocytes. Endocrinology. 2009; 150:1688–1696.

6. Luk T, Malam Z, Marshall JC. Pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor (PBEF)/visfatin: a novel mediator of innate immunity. J Leukoc Biol. 2008; 83:804–816.

7. Nickel N, Jonigk D, Kempf T, Bockmeyer CL, Maegel L, Rische J, et al. GDF-15 is abundantly expressed in plexiform lesions in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension and affects proliferation and apoptosis of pulmonary endothelial cells. Respir Res. 2011; 12:62.

8. Otero M, Lago R, Gomez R, Lago F, Dieguez C, Gómez-Reino JJ, et al. Changes in plasma levels of fat-derived hormones adiponectin, leptin, resistin and visfatin in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006; 65:1198–1201.

9. Chung CP, Long AG, Solus JF, Rho YH, Oeser A, Raggi P, et al. Adipocytokines in systemic lupus erythematosus: relationship to inflammation, insulin resistance and coronary atherosclerosis. Lupus. 2009; 18:799–806.

11. Ragheb S, Lisak RP. B-cell-activating factor and autoimmune myasthenia gravis. Autoimmune Dis. 2011; 2011:939520.

12. Khare SD, Sarosi I, Xia XZ, McCabe S, Miner K, Solovyev I, et al. Severe B cell hyperplasia and autoimmune disease in TALL-1 transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000; 97:3370–3375.

13. Shiao YM, Lee CC, Hsu YH, Huang SF, Lin CY, Li LH, et al. Ectopic and high CXCL13 chemokine expression in myasthenia gravis with thymic lymphoid hyperplasia. J Neuroimmunol. 2010; 221:101–106.

14. Yang YH, Huang YH, Lin YL, Wang LC, Chuang YH, Yu HH, et al. Circulating IgA from acute stage of childhood Henoch-Schönlein purpura can enhance endothelial interleukin (IL)-8 production through MEK/ERK signalling pathway. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006; 144:247–253.

15. Mills JA, Michel BA, Bloch DA, Calabrese LH, Hunder GG, Arend WP, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Arthritis Rheum. 1990; 33:1114–1121.

16. McDuffie FC, Sams WM Jr, Maldonado JE, Andreini PH, Conn DL, Samayoa EA. Hypocomplementemia with cutaneous vasculitis and arthritis. Possible immune complex syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 1973; 48:340–348.

17. Chen T, Guo ZP, Zhang YH, Gao Y, Liu HJ, Li JY. Elevated serum heme oxygenase-1 and insulin-like growth factor-1 levels in patients with Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Rheumatol Int. 2011; 31:321–326.

18. Wang J, Zhang QY, Chen YX. Effects of Astragalus membranaceus on cytokine secretion of peripheral dendritic cells in children with Henoch-Schonlein purpura in the acute phase. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2009; 29:794–797.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download