Abstract

Background

Cholinergic urticaria is a type of physical urticaria characterized by heat-associated wheals. Several reports are available about cholinergic urticaria; however, the clinical manifestations and pathogenesis are incompletely understood.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to investigate the clinical characteristics of cholinergic urticaria in Korea.

Methods

We performed a retrospective study of 92 patients with cholinergic urticaria who were contacted by phone and whose diagnoses were confirmed by the exercise provocation test among those who had visited The Catholic University of Korea, Catholic Medical Center from January 2001 to November 2010.

Results

All 92 patients were male, and their average age was 27.8 years (range, 17~51 years). Most of the patients had onset of the disease in their 20s and 30s. Non-follicular wheals were located on the trunk and upper extremities of many patients, and the symptoms were aggravated by exercise. Eight patients showed general urticaria symptoms and 15 had accompanying atopic disease. Forty-three patients complained of seasonal aggravation. Most patients were treated with first and second-generation antihistamines.

Cholinergic urticaria is a physical type of urticaria caused by an increase in core body temperature after exercise, intake of spicy foods, or exposure to stress1.

Lesions appear as itchy, numerous, small, 1 to 5 mm papules or wheals that last for a few minutes to a hour1,2. It is not difficult to diagnose cholinergic urticaria from these typical clinical findings; however, treatment and epidemiology of the disease, as well as several clinical characteristics have not been established3.

It is not rare to encounter patients with cholinergic urticaria in clinical practice, but there are only a few domestic reports in Korea. We investigated 92 patients with cholinergic urticaria, who had visited The Catholic University of Korea, Catholic Medical Center within the past 10 years, to identify the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of the disease.

This study was conducted on 92 patients who were contacted by phone among 185 patients diagnosed with cholinergic urticaria through the exercise provocative test from January 2001 to November 2010 at The Catholic University of Korea, Catholic Medical Center. None of the patients had co-morbid aquagenic urticaria.

We performed medical records analyses and phone inquiries for the 92 patients with cholinergic urticaria to identify gender, age, time of onset, disease duration, lesion location, clinical and systemic symptoms, and existence of other types of urticaria, aggravating factors, seasonal exacerbation and reduction of perspiration, and associated atopic diseases and treatments.

We showed patients photos representing follicular wheals, non-follicular wheals, erythema, and angioedema and asked them to select all photos applicable to their recent symptoms. This process was performed in 43 of the 92 patients using mobile phone texting and e-mail.

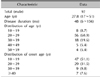

All 92 patients were men, with a mean age of 27.8 years (range, 17~51 years). Fifty-six (60.9%) patients were in their 20s and 18 (19.6%) patients were in their 30s. According to analysis of disease onset, 47 (51.1%) patients contracted the disease in their 10s, 29 (31.5%) in their 20s, nine (9.8%) in their 30s and seven (7.6%) in their 40s or older (Table 1).

Mean disease duration was 48 months (range, 6~156 months). Thirty-seven (40.2%) patients presented at 1 to 3 years, 22 (23.9%) at <1 year, 15 (16.3%) at 3 to 5 years, 14 (15.2%) at 5 to 10 years, and four (4.4%) at ≥10 years.

We investigated the shapes of the skin lesions in 43 of the 92 patients. Among them, 29 (67.5%) had non-follicular wheals, five (11.6%) had follicular wheals, and three (7.0%) showed a mixed type of non-follicular and follicular wheals. In addition, five (11.6%) patients showed erythematous lesions without wheals and one (2.3%) had accompanying angioedema (Fig. 1).

We investigated the distribution of the lesions in all 92 patients and found that 92 patients (98.9%) had lesions distributed on the trunk and upper limbs, and two had multiple macules that did not accompany a peri-lesional halo on the palms (Fig. 1E). Distribution on the face and scalp was observed in 20 (21.7%) patients, on the lower limb in 18 (19.6%), and one (1.1%) had mucosal edema (Table 2).

Forty-three (46.7%) patients complained of only pruritus, 16 (17.4%) complained of soreness, and 33 (35.9%) complained of both. Interestingly, two (2.2%) complained of scalp soreness without showing any notable skin lesions.

Eighty-four (91.3%) of the 92 patients had no general symptoms accompanying urticaria, but five (5.4%) patients had dizziness and three (3.3%) had chest tightness.

Eleven (12.0%) patients had other types of urticaria co-morbidly with cholinergic urticaria. Six (6.5%) patients had dermographism, three (3.3%) had cold urticaria, and two (2.2%) had food-induced urticaria.

Among them, exercise was identified as the aggravating factor in 59 (64.1%) patients followed by a bath in 29 (31.5%), eating hot or spicy food in 23 (25.0%), and psychological stress in 18 (19.6%). Additionally, 43 (46.7%) patients complained of heat-induced or alcohol-induced exacerbation, whereas others had no such factors (Table 2).

Forty-three (46.7%) patients stated that they had a seasonal aggravation; 22 (23.9%) complained of exacerbation in the summer, 18 (19.6%) complained of exacerbation in the winter, and three (3.3%) complained of disease exacerbation in spring or autumn. Twenty-three (25%) stated reduced sweat secretion.

Fifteen (16.3%) patients had atopic diseases, and six had two or more atopic diseases co-morbidly. The accompanying disease in 10 (10.9%) patients was atopic dermatitis, followed by eight (8.7%) with allergic rhinitis, and one each (1.1%) with allergic conjunctivitis and asthma (Table 2).

We investigated all medications prescribed to the patients, and the most prescribed therapeutic agent was a second-generation antihistamine for 78 (84.8%) patients, followed by a first-generation antihistamine for 32 (34.8%) patients. In addition, ten (10.9%) and five (5.4%) patients were treated with topical or systemic steroids, respectively. Six (6.5%) patients were just observed without any special treatment, whereas two (2.2%) were transferred to another hospital or refused treatment.

Cholinergic urticaria is a fairly common type of hives, comprising about 30% of physical urticaria and about 7% of chronic urticaria4. Prevalence is higher in younger patients, particularly those between 23 to 28 years of age5. Accordingly, the mean age of patients in our study was 27.8 years old. In >80% of cholinergic urticaria cases, the age of onset is 10 to 20 years of age. The reason that the onset age is higher in our study may be due to the fact that teenagers find it more difficult to make time to visit the hospital. The mean duration of disease was 48 months in our study, which was much shorter than the 7.5 years reported by other studies6, probably because the majority included in our patient group were those who visited the hospital recently without a follow-up period.

As the 92 patients were all men in our study, we were interested in the gender prevalence in cholinergic urticaria. According to Onn et al.7, who reported the family history of cholinergic urticaria for the first time, only the father and the son developed cholinergic urticaria in a four member family with an urticaria history. Thus, we ruled out X-linked inheritance, but this observation suggests the possibility of autosomal dominant inheritance7. In contrast, all six patients were women in the study of Kozaru et al.6, and a report on the prevalence of cholinergic urticaria in those 10 to 20 years old found that the prevalence of the disease in women was 1.2 times higher than that in men5. The reason for male predominance is considered that many of our patients visited the hospital to obtain medical reports for military affairs, and the frequency of being exposed to the aggravating factors such as exercises is a bit higher in men. However, more studies on the genetic and environmental factors that affect cholinergic urticaria prevalence are required.

We studied the skin lesion morphology in 43 patients and more than half had non-follicular wheals. We found various shapes of lesions incurred such as wheals along the follicles and erythema with no prominent lesions and the mixed type of non-follicular and follicular lesions.

This study had a limitation in that the morphology of the skin lesions was reported by a patient statement after they looked at photographs of various forms of cholinergic urticaria. It is known that follicular and non-follicular forms have different pathogenic mechanisms8. It is hypothesized that hypersensitivity to autologous serum and sweat may be involved in the wheal formation of the former and the latter type, respectively8. However, 20% of our patients had lesions other than these two types. Thus, it will be necessary to study the association between the clinical form and pathogenesis in cholinergic urticaria.

Eight (8.7%) of our 92 patients had general urticaria symptoms such as dizziness and chest tightness. The existence of bronchial hypersensitivity had recently been verified in some patients with cholinergic urticaria, and it was identified to be related to the duration or the degree of hives9,10. Thus, inquiries about respiratory symptoms during a physical examination could be important for patients with cholinergic urticaria.

Cold type urticaria is the most common co-morbid physical urticaria with cholinergic urticaria11,12,13. In our study, three (3.3%) patients had co-morbid cold urticaria and six (6.5%) had co-morbid dermographism.

The prevalence of atopic dermatitis in our patients with cholinergic urticaria was 51.4%, and the prevalence of allergic rhinitis was 34.2%, which were higher than the general reported prevalence14. The prevalence of cholinergic urticaria in patients with atopic dermatitis remains unclear, but the co-morbidity of cholinergic urticaria and atopic dermatitis is relatively frequent. In this study, the prevalence of atopic disease was 16.3%; 10.9% had atopic dermatitis, and 8.7% had allergic rhinitis. The observation that the prevalence of atopic disease in patients with cholinergic urticaria is not so different from that in the general population may result from recall bias. This study was conducted retrospectively; thus, it may have been difficult for the adult patients to remember past atopic symptoms. When patients with atopic dermatitis complain of stinging and itchy skin and atopic dermatitis symptoms exacerbated by hot weather, physicians may misdiagnose it as cholinergic urticaria. Given the actual conditions of out-patient medical examinations in Korea, where it is difficult to make a confirmative diagnosis by implementing the exercise-induced test in patients with atopic dermatitis who complain of these symptoms, there is a possibility of overestimating the association between cholinergic urticaria and atopic dermatitis. Because previous studies that have reported a high prevalence of atopic dermatitis were conducted in a small number of subjects14, the prevalence of atopic diseases in patients with cholinergic urticaria should be identified through larger scale studies.

Interestingly, 17 of the 18 patients who experienced aggravation in winter complained of decreased perspiration, indicating that about 74.0% of 23 patients who complained of a decreased perspiration also complained of winter symptom exacerbation. Rho15 reported that cholinergic urticaria symptoms can be aggravated due to xerosis-induced sweat duct occlusion in winter. In their report, 64 (26.1%) of 245 patients showed symptom onset only in winter, and 17 complained of decreased perspiration. Kobayashi et al.16 explained that the sweat pores in the epidermis are blocked by a widening of the keratin plug or sweat duct obstruction in cholinergic urticaria patients, resulting in inflammatory substances contained in sweat being refluxed into the dermis causing urticaria wheals. Therefore, patients whose symptoms are exacerbated in summer as sweating increases (23.0%) and those whose symptoms are exacerbated in winter (19.6%) as sweating decreases probably have different pathogenic mechanisms.

In this study, most patients were treated with first and second-generation antihistamines, which provided only temporary relief. Some authors who have suggested the pathogenesis of cholinergic urticaria including occlusion of sweat duct and allergic reaction to sweat recommend that the treatment method should vary depending on the pathogenesis16,17,18. Some reported successful treatment of cholinergic urticaria using the recombinant monoclonal antibody omalizumb, which binds the immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibody receptor to modulate IgE-mediated allergic symptoms19. Omalizumab is expected to be a new therapeutic agent for refractory patients with cholinergic urticaria. However, this will require a systematic approach to observe clinical characteristics of patients and an in-depth study on the pathogenesis to develop an effective treatment method for cholinergic urticaria.

We conducted a retrospective study of 92 patients who were diagnosed with cholinergic urticaria from January 2001 to November 2010. The mean age of participants was 27.8 years old, and they were all men. First disease onset was in their 20s and 30s, and the mean duration of the disease was 48 months. Lesions were frequently found on the upper trunk and proximal limbs as nonfollicular wheals, and exacerbation was most often caused by exercise. General symptoms were found in eight (8.7%) patients, and atopic disease occurred in 15 (16.3%). Forty-three (46.7%) patients indicated seasonal variations in symptoms. In particular, most patients who complained of winter exacerbations also complained of decreased sweat secretion. The patients had been treated with first and second-generation antihistamines, but their responses were poor. This study had limitations because skin morphology study largely depends on statement of patients by using the given photo in a retrospective manner.

As dermatologists, we should have interest in various characteristics of patients with cholinergic urticaria and try to provide medical care services with such an understanding. Further investigation and follow-up studies are necessary to better understand the pathogenesis and treatment methods for cholinergic urticaria.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Clinical photographs of cholinergic urticaria. (A) Typical non-follicular wheals. (B) Follicular wheals. (C) Mixed type of follicular wheals (arrows) and non-follicular wheals (arrowheads). (D) Erythema without wheals. (E) Multiple red spots on the palm without a perilesional halo. |

References

1. Krupa Shankar DS, Ramnane M, Rajouria EA. Etiological approach to chronic urticaria. Indian J Dermatol. 2010; 55:33–38.

3. Moore-Robinson M, Warin RP. Some clinical aspects of cholinergic urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 1968; 80:794–799.

4. Kontou-Fili K, Borici-Mazi R, Kapp A, Matjevic LJ, Mitchel FB. Physical urticaria: classification and diagnostic guidelines. An EAACI position paper. Allergy. 1997; 52:504–513.

5. Zuberbier T, Althaus C, Chantraine-Hess S, Czarnetzki BM. Prevalence of cholinergic urticaria in young adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994; 31:978–981.

6. Kozaru T, Fukunaga A, Taguchi K, Ogura K, Nagano T, Oka M, et al. Rapid desensitization with autologous sweat in cholinergic urticaria. Allergol Int. 2011; 60:277–281.

7. Onn A, Levo Y, Kivity S. Familial cholinergic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996; 98:847–849.

8. Horikawa T, Fukunaga A, Nishigori C. New concepts of hive formation in cholinergic urticaria. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2009; 9:273–279.

9. Petalas K, Kontou-Fili K, Gratziou C. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness in patients with cholinergic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009; 102:416–421.

10. Asero R, Madonini E. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness is a common feature in patients with chronic urticaria. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2006; 16:19–23.

11. Yang JS, Park HJ, Byun DG. A case of cold urticaria and cholinergic urticaria in the same patient. Korean J Dermatol. 2003; 41:123–126.

12. Ormerod AD, Kobza-Black A, Milford-Ward A, Greaves MW. Combined cold urticaria and cholinergic urticaria--clinical characterization and laboratory findings. Br J Dermatol. 1988; 118:621–627.

13. NeittaanmaÄki H. Cold urticaria. Clinical findings in 220 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985; 13:636–644.

14. Takahagi S, Tanaka T, Ishii K, Suzuki H, Kameyoshi Y, Shindo H, et al. Sweat antigen induces histamine release from basophils of patients with cholinergic urticaria associated with atopic diathesis. Br J Dermatol. 2009; 160:426–428.

15. Rho NK. Cholinergic urticaria and hypohidrosis: a clinical reappraisal. Dermatology. 2006; 213:357–358.

16. Kobayashi H, Aiba S, Yamagishi T, Tanita M, Hara M, Saito H, et al. Cholinergic urticaria, a new pathogenic concept: hypohidrosis due to interference with the delivery of sweat to the skin surface. Dermatology. 2002; 204:173–178.

17. Adachi J, Aoki T, Yamatodani A. Demonstration of sweat allergy in cholinergic urticaria. J Dermatol Sci. 1994; 7:142–149.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download