INTRODUCTION

Eccrine porocarcinoma (EPC) is a rare malignant tumor related to the sweat gland duct. It is a counterpart of eccrine poroma of a benign sweat gland neoplasm. Approximately 20% of EPC recur after excision, 20% have nodal metastasis, and 12% develop distant metastasis. Patients with metastasis have a high mortality rate1,2. In the course of development, recurrence, or metastasis, neoplasm often changes from well-differentiated form into poorly-differentiated form. This transformation, called as dedifferentiation, sometimes makes it difficult to confirm that these primary and secondary lesions are the same. By dedifferentiation, prognosis of patients generally worsens. Therefore, it is very important to diagnose these recurrent and metastatic lesions quickly and accurately. Herein, we report a rare case of dedifferentiated EPC with recurrence and metastasis, and discuss utilities of immunostain in diagnosis, especially that of S-100 protein.

CASE REPORT

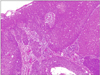

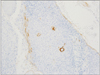

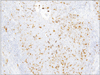

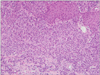

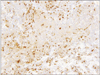

A 78-year-old Japanese woman visited our hospital, complaining about the left inguinal skin tumor, increasing in size (Fig. 1). Since biopsy revealed the lesion is malignant, the dermal tumor was excised, and local lymphadenectomy was also performed. Neoplastic cells proliferated in lobular downwards growth, and connected to the epidermis (Fig. 2). The neoplastic cells have atypical oval nucleus, and mitotic figures were found. A small number of lumens were observed in the nests. Melanin granules were not found. Immunostain for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) is positive at the rims of the lumens (Fig. 3). Majority of the lesion was immunoreactive for AE1/AE3. On immunohistochemistry for S-100 protein, scattered stained dendritic cells were found (Fig. 4). On that for HMB-45 and Melan-A, scattered positive cells were found partially. Some tumor cells appeared to be periodic acid schiff (PAS) stain positive, and PAS-positive substance was digested by diastase. There was no nodal metastasis. According to these facts, the diagnosis of EPC was confirmed. After fourteen months, a tumor occurred in the same location. Epithelioid cells diffusely proliferated in the subcutaneous tissues (Fig. 5). The histology looked like epithelioid melanoma. Immunostain for CEA and EMA was negative, but immunoreactivity for AE1/AE3 was diffusely observed. Scattered S-100 protein positive cells were found (Fig. 6). But, immunoreactivity for Melan-A and HMB-45 disappeared. The cells contain no PAS-positive glycogen. Since the tumor location is same with that of the primary lesion, and the stainings for S-100 protein and AE1/AE3 between the two are similar, the lesion was diagnosed as recurrent EPC with dedifferentiation. Three months later, metastasis to the lungs was found. Biopsied specimens showed similar histologic findings of the secondary inguinal lesion, and the diagnosis of dedifferentiated metastatic EPC was made. Immunoreactivity for AE1/AE3 was diffusely observed, and scattered immunoreactive cells for S-100 protein were also maintained. Nevertheless, immunostains for EMA, HMB-45, and Melan-A were all negative. Two months later, the patient died for aggravation of general condition.

DISCUSSION

EPC, known as malignant eccrine poroma or eccrine adenocarcinoma, is a rare type of malignant sweat gland tumor. The lesions are clinically observed as verrucous plaques or polypoid protrusions mimicking squamous cell carcinoma or Bowen's disease. Despite the palms and soles having a concentration of eccrine sweat glands, about 30% of EPCs develop on the legs, and 20% on the feet. Histologically, ductal differentiation of poromatous epithelial cells is the hallmark, but epidermoid differentiation appears simultaneously. The tumor cells showed cytologic pleomorphism and frequent, often abnormal, mitotic figures. Although glandular differentiation is characteristic, poorly differentiated EPC may not show obvious duct formations.

Immunohistochemistry is useful in the definite and differential diagnosis of EPC. The poroid cells were diffusely positive for cytokeratin. EMA and CEA are reported to be positive at rim of the lumen. But, poorly differentiated EPC with no luminal differentiation did not show immune-positivity for CEA3,4. The presence of scattered dendritic melanocytes, positive for S-100 protein and HMB-45, has been reported to be in both benign and malignant eccrine poroma, as in the present case. These cells were intermingled with the tumor cells. The cells sometimes contain melanin granules5. On the other hand, in some cases of EPC, no melanocytes were observed3. Cases of pigmented EPC with melanin also being present in the metastases was reported6,7. Since neoplastic cells with myoepithelial differentiation exhibits immunoreactivity for S-100 protein in eccrine spiradenoma, eccrine acrospiroma, and dermal mixed tumor, the stain is useful for the differential diagnosis of these tumors between EPC8. In the tumors with myoepithelial differentiation, the positive cells are neoplastic cells, whereas in EPC, the positive cells are intermingled dendritic cells.

Dedifferentiation is defined as the histological progression of a low-grade malignant neoplasm to a high-grade neoplasm in which the original line of differentiation is no longer evident. The phenomenon is also known as high grade transformation. It is common in sarcomas and salivary gland carcinoma, like as liposarcoma, chondrosarcoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberance, adenoid cystic carcinoma, and epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma9,10. But, it is sometimes observed in many neoplasms. Dedifferentiation in the recurrent and metastatic sites occurs frequently, similar to the nodal metastasis of poorly differentiated carcinoma from primarily well-differentiated carcinoma. If the primary and secondary lesions have common structural and cellular features, the diagnoses of recurrence and metastasis are easy to perform. But, dedifferentiation sometimes makes it difficult to confirm that these lesions are of the same one.

Since luminal structure disappeared in the recurrent and metastatic dedifferentiated lesions of the present case, immunostaining for CEA was useless in the diagnosis. Besides that, immunostain for EMA was positive in the primary lesion, however, the stain was negative in the local-recurrent and metastatic lesions. Although the recurrent lesion in the present case showed 'melanoma-like' dedifferentiated histologic findings, it occurred in the same site as primary lesion. The metastatic lesions showed the same histologic findings as the local-recurrent lesion. No other carcinoma was clinically proven in any examinations. Therefore, all the lesions were certainly from the same origin, in spite of the different histologic findings. And finally, the presence of scattered cells immunoreactive for S-100 protein was the definite evidence. Immunostain for HMB-45 and Melan-A may be a useful tool, too. But, in this case, recurrent and metastatic lesions did not show positivity for those antibodies. The S-100 protein positive cells in the recurrent and metastatic lesions were thought to be dendritic cells, not melanocytes. To conclude, immunohistochemistry, especially the S-100 protein, is useful in the diagnosis of EPC, specifically to the dedifferentiated EPC.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download