Abstract

Background

Although tinea unguium in children has been studied in the past, no specific etiological agents of onychomycosis in children has been reported in Korea.

Methods

We reviewed fifty nine patients with onychomycosis in children (0~18 years of age) who presented during the ten-year period between 1999 and 2009. Etiological agents were identified by cultures on Sabouraud's dextrose agar with and without cycloheximide. An isolated colony of yeasts was considered as pathogens if the same fungal element was identified at initial direct microscopy and in specimen-yielding cultures at a follow-up visit.

Results

Onychomycosis in children represented 2.3% of all onychomycosis. Of the 59 pediatric patients with onychomycosis, 66.1% had toenail onychomycosis with the rest (33.9%) having fingernail onychomycosis. The male-to-female ratio was 1.95:1. Fourteen (23.7%) children had concomitant tinea pedis infection, and tinea pedis or onychomycosis was also found in eight of the parents (13.6%). Distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis was the most common (62.7%) clinical type. In toenails, Trichophyton rubrum was the most common etiological agent (51.3%), followed by Candida albicans (10.2%), C. parapsilosis (5.1%), C. tropicalis (2.6%), and C. guilliermondii (2.6%). In fingernails, C. albicans was the most common isolated pathogen (50.0%), followed by T. rubrum (10.0%), C. parapsilosis (10.0%), and C. glabrata (5.0%).

Onychomycosis denotes nail infection from dermatophytes, nondermatophytic molds, or yeasts while tinea unguium refers specifically to the infection of the nail plate by dermatophytes. Onychomycosis is the most prevalent nail disease and accounts for approximately 50 percent of all onychopathies, and tinea unguium is a specific sub-diagnostic category of onychomycosis. The increasing prevalence of this disease may be secondary to the use of tight-fitting shoes, increasing numbers of immunosuppressed individuals, and the increased used of communal locker rooms1.

It has been known that onychomycosis in children is less common than in adults, but its frequency has been on the rise1-15. Though several case have been reported on onychomycosis in children these past three decades16-18, the causative pathogens of onychomycosis had not been reported among Korean children. Therefore, this study was designed to investigate clinical features and etiological agents of onychomycosis in children.

A retrospective review of pediatric onychomycosis at the Department of Dermatology, Dongguk University Gyeongju Hospital from 1999 to 2009 identified a total of 59 children under age 18 who had clinical signs of onychomycosis and were diagnosed with onychomycosis by 15% potassium hydroxide (KOH) test and fungal culture. Among these patients, 39 children had toenail onychomyocosis, and 20 children had fingernail onychomycosis.

The medical records of the 59 children were reviewed for clinical features, yearly/monthly/seasonal variations in incidence, age, gender, duration of disease, residential distribution, concurrent disease, family history of fungal infections, sites of nail involvement, clinical type, and treatment strategies. According to the classification of Baran et al.19, the cases were classified into the following five clinical types: distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis (DLSO), superficial white onychomycosis (SWO), proximal subungual onychomycosis (PSO), endonyx onychomycosis, and total dystrophic onychomycosis (TDO) (Fig. 1, 2).

After sterilization with 75% alcohol, a sample was obtained by scraping the hyperkeratotic nail bed with a disposable scalpel. Nail samples were examined under the microscope after 5 minutes of submersion in a 15% KOH clearing solution. Fungal cultures were obtained by inoculating each specimen on three seperate sites of Sabouraud's dextrose agar (with and without 0.5 mg/ml cyclohexamide each with room temperature incubation for from 2- to-4 weeks. Causative pathogens were identified based on gross and microscopic presence of colonies. In cases where the yeasts species had been cultured, the pathogens were identified by using germ tube test and API 20C (BioMerieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) kit. Using a modified English criteria20, onychomycosis due to nondermatophytic molds or yeasts was defined if the 15% KOH test was positive, 3 identical colonies were found in fungal cultures, and the same fungus was identified in repeated cultures.

During the period reviewed in this study, the total number of patients (all ages) with onychomycosis was 2,584. Of these, 59 were children with onychomycosis and accounted for 2.3% of all cases. The yearly incidence was the highest during the periods from July 1999 to June 2000, and from July 2007 to June 2008 (n=9, 15.3%), with the lowest incidence recorded for the period between July 2002 to June 2003 (n=1, 1.7%) (Fig. 3).

In terms of monthly incidence, 12 children developed onychomycosis in January; 8 children in May; 7 children in July; 6 children in March; 4 children each in April, June, August, and November; and 3 children each in July, October, and December; and, one child in September. Seasonally, 22 children had developed onychomycosis during the winter (December through February), 18 children during the spring (March through May), 11 children during the summer (June through August), and 8 children during the fall (September through November) (Fig. 4).

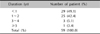

In this group, toenail onychomycosis occurred most commonly among 16, 17, and 18-year-old patients (n=13, 33.3%), followed by 8- to-11-year-old group, (n=10, 25.6%) and 12- to-15-year-old group (n=7, 18.0%). Fingernail onychomycosis occurred most commonly under the age of 3 (n=8, 40.0%), followed by 4- to-7-year-old group (n=7, 35.0%) and 8- to-11-year-old group (n=3, 15.0%). There were no 16- to-18-year-old patients with fingernail lesions (Table 1). The male-to-female ratio was 1.95 : 1, with a predilection for male children (39 versus 20). (Fig. 5).

Among children, the usual duration of onychomycosis was less than a year (29 children, 49.1%). In 25 children (42.4%), the condition persisted 1- to-2 years, and persisted 3- to-4 years in 3 children (5.1%). The remaining 2 children (3.4%) experienced onychomychosis for at least 5 years (Table 2).

To determine the correlation between socioeconomic conditions and prevalence of pediatric onychomycosis, residential distribution of the patients were investigated. Patients living in urban area (45 children, 76.3%) were more likely to have onychomychosis than those living in rural areas (14 children; 23.7%) (Fig. 6).

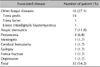

Out of the total 59, 32 children (54.2%) had medical conditions in addition to onychomychosis. Concurrent fungal diseases was the most common (16 cases, 27.1%). In particular, there were 14 cases (23.7%) of tinea pedis and single case of tinea faciei and of erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica each. The rest of the 32 cases were atopic dermatitis (7 cases; 11.8%), pneumonia (4 cases; 6.8%), meningitis (1 case; 1.7%), cerebral hematoma (1 case; 1.7%), epilepsy (1 case; 1.7%), femur fracture (1 case; 1.7%) and depression (1 case; 1.7%) (Table 3). Eight patients (13.6%) hada family history of fungal infections. Of those eight, 5 fathers (8.5%) were known to have fungal infection; 2 mothers (3.4%) with fungal infections; and both parents in a single case (1.7%) (Table 4).

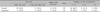

Of the 59, 39 children (66.1%) had toenail onychomycosis, and 20 (33.9%) had fingernail onychomycosis. Among the toenail onychomycosis group, 18 children (46.5%) had involvement of a big toenail alone, 15 (38.5%) had multiple toenail involvement including a big toenail, and 9 (15.4%) had multiple toenail involvement excluding a big toenail. In the fingernail onychomychosis group, 9 children (45.0%) had involvement of a thumbnail alone, 7 (35.0%) had multiple fingernails involvement excluding a thumbnail, and 4 (20.0%) had multiple fingernail involvement including a thumbnail (Table 5).

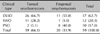

The DLSO was the most common type of toenail onychomycosis (n=26, 66.7%), followed by SWO (n=11, 28.2%) and PSO (n=2, 5.1%). DLSO was also the most common type of fingernail onychomycosis (n=11, 55.0%), and was followed by PSO (n=8, 40.0%) and SWO (n=1, 5.0%). In the overall group, DLSO was the most common (n=37, 62.7%), followed by SWO (n=12, 20.3%), and PSO (n=10, 17.0%) (Table 6). Yellow spike onychomychosis was observed in a single case.

The causative pathogens of toenail onychomycosis were isolated by fungal culture in 28 out of 39 cases upon exclusion of 6 contaminated cases and 5 negative cultures. The resulting positive culture rate was 71.8%. Trichophyton rubrum was most commonly isolated organism (20/39, 51.3%), followed by Candida species (8/39, 20.5%). Of the Candida species, C. albicans was the most common pathogen (4/39, 10.2%), followed by C. parapsilosis (2/39, 5.1%), C. tropicalis, and C. guilliermondii (1/39, 2.6%).

In fingernail onychomycosis, causative pathogens were isolated by fungal culture among 15 out of 20 cases; there were 3 contaminanted culture results and and 2 negative culture results. The positive culture rate was 75.0%. Unlike the toenail group, Candida species was more commonly isolated (13/20, 65.0%), than T. rubrum (2/20, 10.0%) in the fingernail onychomychosis group. Of the Candida species, C. albicans was the most common pathogen (10/20, 50.0%), followed by C. parapsilosis (2/20, 10.0%), and C. glabrata (1/20, 5.0%). No cases of nondermatophytic molds were identified in either finger or toenail onychomychosis among children.

In the overall analysis, T. rubrum was most commonly isolated organism (22/59, 37.3%) and wasfollowed by Candida species (21/59, 35.6%). Of the 21 Candida-related cases, C. albicans was most common (14/21, 23.7%), followed by C. parapsilosis (4/21, 6.8%), C. tropicalis, C. guilliermondii and C. glabrata (1/21, 1.7%) (Table 7).

Twenty-nine of the children (49.1%) had received oral administration of itraconazole and application of antifungal nail lacquer or cream. For 22 children (37.3%), terbinafine was administered in combination with antifungal nail lacquer or cream. To the remaining 8 children (13.6%), only antifungal nail lacquer or cream was applied.

To patients who refused to take oral medication, only topical treatment was applied (Table 8).

In the past, the age standard of pediatric onychomycosis have been under the age of 1516-18. Recently, however, 16~18 age group were also included in the subject of pediatric onychomycosis5-8,15,21.

The reported prevalence of onychomycosis ranges from 0.2% to 2.6% among children approximately 1/30th that of adults4,9. The low prevalence of pediatric onychomycosis is probably due to faster nail growth, smaller surface area available for exposure to onychomycotic pathogens, lack of cumulative trauma, and reduced environmental exposure to public places such such as locker rooms and public showers that harbor high densities of infective hyphae and spores4-7,13-15. Though in this study, exact prevalence of onychomycosis was not investigated to a control pediatric population, the relative percentage of pediatric-to-adult onychomychosis cases, 2.3%, was the same as the percentage figure reported by by Choi et al.17. Onychomycosis in the study population showed the highest incidence in the winter (37.3%), which was a similar finding in a study by Hwang et al.22 on onychomycosis among the adult population (30.7%).

Unlike this study, on the other hand, there have been reports that pediatric onychomycosis showed the highest incidence in the summer17,23-25. In this study, the rates of the onychomycosis did not increase with advancing age, however, other reported results showed that the incidence was increased with advancing age7,8,15.

Adolescents between ages of 16 to 18 years formed the highest proportion of patients (33.3%), as in a report by Lange et al.8 In contrast to other reports, we did not find that the incidence increased with advancing age7,8,12,15. In the case of fingernail onychomychosis, patients less than 3 years old comprised the highest proportion (40.0%) as in the report by Lange et al.8 On the contrary to other reports, the incidence tended decrease with age. Male children were more likely to present with onychomycosis in female children (1.95 : 1) as reported by Choi et al.17, Lateur et al.5 and Romano et al.6.

In our pediatric population, the lesions most commonly persisted for less than 1 year in 29 children (49.1%). According to the study by Hwang et al.22, onychomycosis persisted from 5 to 9 years among 33.7% of adult patients. In a study by Sohn and Lee26, it persisted for at least 10 years in 54.4% of elderly patients. The reason why onychomycosis in children is less persistent may be that they are treated early because unlike in the past, parents take an active effort to treatment.

The prevalence was higher in patients living in urban areas than in rural areas, which was not consistent with the report of Gunduz et al.9 that the prevalence was higher in schoolchildren aged between 7 and 14 in rural areas. It might be because rural areas were administratively reorganized into cities, and most people in rural area tended to think nothing of onychomycosis.

In the case of concurrent diseases, it was reported that tinea pedis was most common concurrent disease with onychomycosis, especially toenail onychomycosis4,8,15. Also in this study, tinea pedis comprised the highest proportion (23.7%) of concurrent diseases.

In the study by Lange et al.8, the concurrent rate of onychomycosis and tinea pedis was 15.0%, and in that of Rodríguez-Pazos et al.15, the concurrent rate was 17.9%. In a study by Gupta et al.4, the concurrent rate reached 47.0%. It is known that onychomycosis is more likely to occur in patients with Down syndrome or with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection4-6,9,13-15. In this study, however, there was no patient with Down syndrome or HIV infection.

Any family history of tinea pedis or onychomycosis was thought to be a potential source of onychomycosis infection4,6,8,14,15,27, and our study did identify children who have a significant family history with 8.5% of children who had fathers with history of fungal infection. Thus, it may be necessary to evaluate family members for fungal infection in order to decrease the chance of re-infection.

Similarly to previous findings4,5,15, toenail infections comprised a higher proportion of the overall onychomychosis. 39 of the children (66.1%) had toenail onychomycosis, whereas 20 children (33.9%) had fingernail onychomycosis. Interestingly, the relative percentage of fingernail onychomycosis to the whole represents a larger proportion when compared to the relative percentage reported for adults22. This was suggested to be a result of finger sucking being a habit limited to children, and as such finger nail infections to tend to reflect the Candida species of oral flora5,8. According to the study of by Hwang et al.22, onychomycosis in adults most commonly occurred across multiple digits, including a big toenail or a thumbnail. In this study, however, most children had a single digit involvement of either a big toenail or a thumbnail alone.

In our study, DLSO-type was found in 62.7% of children-a finding consistent with reported results2,4,5,8,9,11,15. SWO and PSO were found in 20.3% and 17.0% of patients, respectively. Unlike the reports by Gupta et al.4 and Rodríguez-Pazos et al.15 however, TDO was not found in our pediatric population. In the study of Hwang et al.22 SWO comprised just 8.5% of the whole, but SWO was found to represent 20.3% of our pediatric cases. This higher rate of incidence among children implies that SWO-type onychomychosis should be suspected for a child with whitish, friable nails.

It is known that T. rubrum, T. mentagrophytes and Candida species are the main causative pathogens of onychomycosis in children5-9,28, and our study reflects these past findings. T. rubrum and Candida species represented 37.3% (22 strains) and 35.6% (21 strains) of all the cases, respectively. However, no colonies of T. mentagrophytes were isolated. In toenail onychomycosis, T. rubrum was most frequent isolates (20 strains; 51.3%) and was similar to the findgins reported by Lange et al.8 Among the cases of fingernail onychomycosis, C. albicans was most frequently isolated (10 strains; 50.0%). C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, C. glabrata and C. guilliermondii were isolated with lesser frequency, as these agents have been reported in the past6,29,30.

There are various treatment regimens for onychomycosis in children. Itraconazole, terbinafine, and fluconazole are oral antifungal agents, and 5% amorolfine nail lacquer, 8% ciclopirox nail lacquer, and bifonazole-urea are local antifungal agents. As a general rule, children are able to undergo the same therapy as adults do, with dosage adjusted according to body weight and age6.

It is known that a combination of oral and topical antifungal treatment is more effective against onychomycosis than single therapy28,31, and in our study, the combination therapy was accepted by 86.4% of patients.

In summary, onychomycosis in children has many different characteristics compared with onychomycosis in adult. Among children, onychomycosis usually did not persist for more than a year, which is not the case in adults22,26. In the pediatric population, we did not find any underlying diseases, associated with onychomychosis such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus22,26. According to the study of Hwang et al.22, onychomycosis most commonly occurred across multiple digits including a big toenail or a thumbnail. In this study, however, most children only had a single digit involvement of a big toenail or a thumbnail alone, and the prevalence of fingernail onychomycosis in children comprise a large proportion compared to the reported prevalence of fingernail onychomycosis in adult. Furthermore, unlike adult patients, the incidence of SWO type and Candida onychomycosis was relatively high in child patients. It is well known that the treatment response of the SWO type and Candida onychomycosis is better than the other presentations of onychomycosis31. In this study, the exact cure rate of onychomycosis was not investigated, but as with the high rate of treatment compliance in pediatric populations, most patients showed clinical and mycological improvement from the combination of oral and topical antifungal therapy (Table 9).

In conclusion, a number of children with onychomycosis were found by clinical examinations and isolation of causative pathogen. Dermatophytes and Candida species were identified as the causative pathogens. The results of this study suggest that careful mycological examination should be performed on children with onychopathies in order to identify onychomycosis which have different characteristics from that of the adult population.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis due to Trichophyton rubrum in a 3-year-old boy. Yellowish discoloration with subungual hyperkeratosis on the right distal great toenail.

Fig. 2

Superficial white onychomycosis due to Trichophyton rubrum in a 3-year-old girl. Small, white, friable patches are spread on the right great toenail surface.

References

1. Verma S, Heffernan MP. Superficial fungal infections: dermatophytosis, onychomycosis, tinea nigra, piedra. In : Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, editors. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill;2008. p. 1807–1821.

3. Ploysangam T, Lucky AW. Childhood white superficial onychomycosis caused by Trichophyton rubrum: report of seven cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997; 36:29–32.

4. Gupta AK, Sibbald RG, Lynde CW, Hull PR, Prussick R, Shear NH, et al. Onychomycosis in children: prevalence and treatment strategies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997; 36:395–402.

5. Lateur N, Mortaki A, André J. Two hundred ninety-six cases of onychomycosis in children and teenagers: a 10-year laboratory survey. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003; 20:385–388.

6. Romano C, Papini M, Ghilardi A, Gianni C. Onychomycosis in children: a survey of 46 cases. Mycoses. 2005; 48:430–437.

7. Sigurgeirsson B, Kristinsson KG, Jonasson PS. Onychomycosis in Icelandic children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006; 20:796–799.

8. Lange M, Roszkiewicz J, Szczerkowska-Dobosz A, Jasiel-Walikowska E, Bykowska B. Onychomycosis is no longer a rare finding in children. Mycoses. 2006; 49:55–59.

9. Gunduz T, Metin DY, Sacar T, Hilmioglu S, Baydur H, Inci R, et al. Onychomycosis in primary school children: association with socioeconomic conditions. Mycoses. 2006; 49:431–433.

10. Martinez Roig A, Torres Rodriguez JM. Twelve cases of tinea unguium in a pediatric clinic in 9 years. Eur J Pediatr. 2007; 166:975–977.

11. Bonifaz A, Saúl A, Mena C, Valencia A, Paredes V, Fierro L, et al. Dermatophyte onychomycosis in children under 2 years of age: experience of 16 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007; 21:115–117.

12. Leibovici V, Evron R, Dunchin M, Westerman M, Ingber A. A population-based study of toenail onychomycosis in Israeli children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009; 26:95–97.

13. Zac RI, Café ME, Neves DR, E Oliveira PJ, Barbosa VG. Onychomycosis in a very young child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009; 26:761–762.

14. Sachdeva S, Gupta S, Prasher P, Aggarwal K, Jain VK, Gupta S. Trichophyton rubrum onychomycosis in a 10-week-old infant. Int J Dermatol. 2010; 49:108–109.

15. Rodríguez-Pazos L, Pereiro-Ferreirós MM, Pereiro M Jr, Toribio J. Onychomycosis observed in children over a 20-year period. Mycoses. 2011; 54:450–453.

16. Choo EH, Choi GJ, Cho BK. Mycological and clinical study on dermatophytoses in infants and preschoolers. Korean J Dermatol. 1984; 22:369–374.

17. Suh MK, Choi SK, Kim SH, Suh SB, Sung YO, Oh SH. Tinea pedis & tinea manus in children. Korean J Dermatol. 1993; 31:713–719.

18. Lee JH, Chung HJ, Lee KH. A clinical and mycological study on dermatophytoses in children. Korean J Med Mycol. 2002; 7:209–216.

19. Baran R, Hay RJ, Tosti A, Haneke E. A new classification of onychomycosis. Br J Dermatol. 1998; 139:567–571.

21. Lange M, Nowicki R, Barańska-Rybak W, Bykowska B. Dermatophytosis in children and adolescents in Gdansk, Poland. Mycoses. 2004; 47:326–329.

22. Hwang SM, Kim DM, Suh MK, Kwon KS, Kim KH, Ro BI, et al. Epidemiologic survey of onychomycosis in Koreans: multicenter study. Korean J Med Mycol. 2011; 16:35–43.

23. Lim SW, Suh MK, Ha GY. Clinical features and identification of etiologic agents in onychomycosis (1999-2002). Korean J Dermatol. 2004; 42:53–60.

24. Suh MK, Sung YO, Ha GY. Dermatophytoses in Kyongju area. Korean J Dermatol. 1995; 33:294–302.

25. Park JK, Kwon KS, Yu HJ. A clinical study of onychomycosis. Korean J Med Mycol. 2005; 10:46–54.

26. Sohn JK, Lee SH. Onychomycosis in the elderly. Korean J Med Mycol. 2001; 6:77–83.

27. Tullio V, Banche G, Panzone M, Cervetti O, Roana J, Allizond V, et al. Tinea pedis and tinea unguium in a 7-year-old child. J Med Microbiol. 2007; 56:1122–1123.

29. Inanir I, Sahin MT, Gündüz K, Dinç G, Türel A, Arisoy A, et al. Case report. Tinea pedis and onychomycosis in primary school children in Turkey. Mycoses. 2002; 45:198–201.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download