Abstract

Aquagenic urticaria is a rare form of physical urticaria, in which contact with water evokes wheals. A 19-year-old man and a 4-year-old boy complained of recurrent episodes of urticaria. Urticaria appeared while taking a bath or a shower, in the rain, or in a swimming pool. Well-defined pin head to small pea-sized wheals surrounded by variable sized erythema were provoked by contact with water on the face, neck, and trunk, regardless of its temperature or source. Results from a physical examination and a baseline laboratory evaluation were within normal limits. Treatment of the 19-year-old man with 180 mg fexofenadine daily was successful to prevent the wheals and erythema. Treatment with 5 ml ketotifen syrup bid per day resulted in improvement of symptoms in the 4-year-old boy.

Aquagenic urticaria (AU) was first described by Shelley and Rawnsley1, who reported three cases in 1964, and fewer than 100 cases have since been published in the literature. To the best of our knowledge, only one case of AU has been reported in the Korean literature. AU is a rare form of physical urticaria, in which contact with water, regardless of its temperature and source, evokes wheals2. Skin lesions may be confused with eruptions of cholinergic urticaria; however, they cannot be evoked by exercise, sweating, heat, or emotional stress2. Lesions are located mainly on the upper body (neck, trunk, shoulder, arms, and back)2. We present two cases of AU in young patients. Clinical manifestations, diagnostic tests, and available treatments are reviewed.

The first case was that of a 19-year-old man who was referred to our department due to recurrent episodes of urticaria. He presented with a 3-year history of pinpoint sized wheals affecting the shoulders, arms, trunk, abdomen, and back when he took a bath or shower. These symptoms appeared within 10 to 20 minutes of contact with water and provoked intense pruritus. Each episode lasted for 20~40 minutes and spontaneously resolved. The patient did not complain of angioedema, wheezing, or dyspnea with these episodes. He had no personal history of allergies or drug allergy and no family history of urticaria. The diagnosis of AU was confirmed by applying a room temperature wet compress to the upper body for 30 minutes (Fig. 1). A cold-water and hot-water compress were also applied for 30 minutes. In all cases, the response to the tests was positive, with induction of pinpoint wheals at the site of compress application. A water-challenge test with tap water, distilled water, and normal saline showed similar results. A pressure test, exercise test, and ice-cube test were performed to rule out other physical urticaria. A 6,000 gm weight was applied to the skin for a period of 20 minutes. After 8 hours, no lesions had appeared. Lesions were not reproduced after running. An ice-cube-filled plastic bag was applied to the patient's forearm for 20 minutes. No lesions were noted on the forearm after removal of cold stimulation. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of AU was made. He had no treatment history before visiting our clinic. Fexofenadine was prescribed initially at a dose of 180 mg daily for symptom relief. After 2 weeks, no lesions had developed on contact with water. Once the symptoms were relieved, the dose was reduced to 180 mg every other day. The patient was still symptom free at the 1 year follow-up.

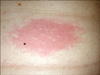

The second case was that of a 4-year-old boy who visited our department due to recurrent episodes of urticaria. He presented with a 1-year history of pinhead sized wheals affecting the face, extremities, chest, abdomen, and back when he took a bath or shower. These symptoms appeared within 10 to 30 minutes of contact with water and provoked pruritus. Each episode lasted for 30 to 60 minutes and showed spontaneous resolution. The patient did not complain of angioedema, wheezing, or dyspnea with these episodes. He had no personal history of allergies or drug allergy and no family history of urticaria. The diagnosis of AU was confirmed by applying a room temperature wet compress to the face for 30 minutes (Fig. 2).

The response to the test was positive, with induction of pinhead sized wheals at the site of compress application. His mother said that the lesions were not reproduced after sweating when the boy played with his friends. An ice-cube-filled plastic bag was applied to the patient's forearm for 20 minutes. No lesions were noted on the forearm after removal of cold stimulation. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of AU was made. He had no treatment history before visiting our clinic. Ketotifen syrup was prescribed initially at a dose of 5 ml bid per day for symptom relief. After 4 weeks, no lesions had developed on contact with water.

Both patients were asymptomatic upon water ingestion. Symptoms appeared after contact with water regardless of its temperature or source. In both cases, the physical examination revealed no other abnormalities. Results from laboratory tests, including a complete blood count with differential, liver function tests, electrolytes, complement (C)3, C4, and urinalysis were normal.

AU is more common in women than in men and appears during puberty or several years later3,4. Most cases are sporadic; however, familial AU has been reported3,5,6. The clinical picture consists of pruritic follicular wheals on skin areas that have come in contact with water. The small pruritic wheals (1~3 mm in diameter) appear in a cholinergic urticaria-like erythematous areas several to 30 minutes after exposure to water and are usually located on the neck, upper trunk, and arms. Wheals generally fade within 30 to 60 minutes. Wheal formation is not influenced by temperature or water source. Alcohol and other organic solvents applied to the skin do not cause wheal formation2. Systemic symptoms are rare but have been reported7,8. AU is sometimes associated with other forms of physical urticaria6,8.

Evaluations for AU consist of a clinical history and water challenge test2,7. The standard test for AU is application of a 35℃ water compress to the upper body for 30 minutes2,9. Water of any temperature can provoke AU; however, keeping the compress at room temperature avoids confusion with cold-induced or local heat urticaria. In addition, a forearm or hand can be immersed in water of varying temperatures9. A diagnosis of AU requires exclusion of other types of physical urticaria, so an exercise test and ice cube test should be performed to rule out other types of physical urticaria9. A summary of the provocation test for other physical urticaria is shown in Table 1. AU should be distinguished from aquagenic pruritus, in which brief contact with water evokes intense itching without wheals or erythema8.

The pathogenesis of AU is not fully known; however, several mechanisms have been proposed10. Interaction with water with a component in or on the stratum corneum or sebum, generating a toxic compound, has been suggested. Absorption of this substance would exert an effect of perifollicular mast cell degranulation with release of histamine1. A study by Sibbald et al.11 demonstrated that complete removal of the stratum corneum appeared to worsen the reaction, rather than prevent urticaria. These authors also demonstrated that pretreatment with organic solvents enhances wheal formation in contact with water. They suggested that enhancement of the ability of water to penetrate the stratum corneum increases wheal formation. Czarnetzki et al.6 hypothesized the existence of a water-soluble antigen at the epidermal layer. The antigen diffuses into the dermis by water and then causes release of histamine from mast cells. Tkach12 hypothesized that hypotonic water sources could lead to osmotic pressure changes, resulting in indirect provocation of urticaria. Others have recently stated that 5% saline was more effective than distilled water for eliciting the wheal-and-flare reaction. They hypothesized that the salt concentration and/or water osmolarity may influence the pathogenic process of AU, possibly by enhancing solubilization and penetration of a hypothetical epidermal antigen, in the same way as has been postulated for enhancement of organic solvents13,14. Another proposed chemical mediator in AU is acetylcholine because of the ability of the acetylcholine antagonist scopolamine to suppress wheal formation when applied to the skin before water contact11. However, another study failed to reproduce this finding when pretreatment with atropine did not result in suppression of subsequent wheal formation6. Methacholine injection testing is negative in patients with AU; however, it is often positive in cholinergic urticaria2. Serum histamine levels are variable from patient to patient2. Antihistamines have been used to treat AU; however, the therapeutic effect and prognosis vary2. In some cases, complete control of symptoms with antihistamine has been reported, whereas in other cases, there is a failure to adequately control symptoms8,15. Refractory cases have been treated with ultraviolet (UV) radiation (both psoralen plus UVA therapy and UVB), either alone or in combination with antihistamines. It is hypothesized that the effect of ultraviolet therapy is mediated by thickening of the epidermis, which may prevent water penetration, interaction with dendritic cells, and immunosuppression or a decreased mast cell response2,16. Barrier methods involving application of oil-in-water emulsion creams on the skin for water protection are effective17. AU responds to stanazolol treatment in human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients4.

We present here two cases of AU that responded to antihistamine treatment. Further study is needed to understand the pathogenesis of AU.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Shelley WB, Rawnsley HM. Aquagenic urticaria. Contact sensitivity reaction to water. JAMA. 1964. 189:895–898.

3. Treudler R, Tebbe B, Steinhoff M, Orfanos CE. Familial aquagenic urticaria associated with familial lactose intolerance. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002. 47:611–613.

4. Fearfield LA, Gazzard B, Bunker CB. Aquagenic urticaria and human immunodeficiency virus infection: treatment with stanozolol. Br J Dermatol. 1997. 137:620–622.

5. Pitarch G, Torrijos A, Martínez-Menchón T, Sánchez-Carazo JL, Fortea JM. Familial aquagenic urticaria and bernard-soulier syndrome. Dermatology. 2006. 212:96–97.

6. Czarnetzki BM, Breetholt KH, Traupe H. Evidence that water acts as a carrier for an epidermal antigen in aquagenic urticaria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986. 15:623–627.

7. Baptist AP, Baldwin JL. Aquagenic urticaria with extracutaneous manifestations. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2005. 26:217–220.

8. Luong KV, Nguyen LT. Aquagenic urticaria: report of a case and review of the literature. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1998. 80:483–485.

9. Panconesi E, Lotti T. Aquagenic urticaria. Clin Dermatol. 1987. 5:49–51.

10. Lee HG, Lee AY, Lee YS. A case of aquagenic urticaria. Korean J Dermatol. 1990. 28:456–458.

11. Sibbald RG, Black AK, Eady RA, James M, Greaves MW. Aquagenic urticaria: evidence of cholinergic and histaminergic basis. Br J Dermatol. 1981. 105:297–302.

12. Tkach JR. Aquagenic urticaria. Cutis. 1981. 28:454. 463.

13. Hide M, Yamamura Y, Sanada S, Yamamoto S. Aquagenic urticaria: a case report. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000. 80:148–149.

14. Gallo R, Cacciapuoti M, Cozzani E, Guarrera M. Localized aquagenic urticaria dependent on saline concentration. Contact Dermatitis. 2001. 44:110–111.

15. Medeiros M Jr. Aquagenic urticaria. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 1996. 6:63–64.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download