Abstract

A 77-year-old woman presented with a trauma to the scalp caused from the blade of a windmill. The condition was persistent from the past 50 years. At the initial examination, a deep, foul-smelling and well-circumscribed ulcer was apparent on the head region, involving the majority of the cranium. Skin biopsy specimens of the lesion were nonspecific. The bone biopsy showed extensive necrotic areas of bone and soft tissues, with lymphocytic exudate foci. A computed tomography scan of the head revealed bone destruction principally involving both the parietal bones, and parts of the frontal and occipital bones. Streptococcus parasanguis was isolated from the skin culture, and Proteus mirabilis and Peptostreptococcus sp. were identified in the cultures from the bone. A long-term treatment with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (1 g/12 h) and levofloxacin (500 mg/day) was prescribed, but even after 6 months, the lesion remained unchanged. The frequency of occurrence of scalp ulcers in dermatological patients is less, principally because of the rich blood supply to this area. We have not found any similar case report of a scalp ulcer secondary to chronic osteomyelitis discovered more than 50 years after the causal trauma. We want to highlight the importance of complete cutaneous evaluation including skin and bone biopsies, when scalp osteomyelitis is suspected.

Chronic osteomyelitis is a severe and persistent infection of the bone and bone marrow. Despite the advances in antibiotic treatments, it is still commonly encountered in areas of poor socio-economic conditions1. In general, chronic osteomyelitis can be related to the spreading of contiguous contaminated source of infection, vascular insufficiency or haematogenous dissemination2. In such cases, complementary tests are essential in order to rule out the possibilities of other similar diseases. In this report, we describe the case of an adult woman with a wide and severe ulcer located on the scalp that was diagnosed as chronic osteomyelitis secondary to a trauma in her early life.

A 77-year-old woman came to us more than 50 years after having suffered a trauma on the scalp from the blade of a windmill. She had never sought any medical help before, and since the accident, had always worn wigs to hide the lesion from her family. Her past medical history was remarkable for diabetes, hypertension, and a basal cell carcinoma located in the nose, which was treated with contact radiotherapy five years before.

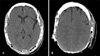

On her first visit to our service, a deep, foul-smelling and well circumscribed ulcer was apparent on the head region, involving the majority of the cranium including not only both the parietal areas but also the occipital and frontal ones (Fig. 1). Craneal bone destruction was evident, and the outer meningeal layer was exposed. Local infection signs such as, draining sinus tracts and swelling were also observed. No systemic symptoms were present, and there no regional lymph node metastases was found by palpation. In laboratory examinations, biochemical tests detected high levels of C-reactive protein (6.39 mg/dl) and high globular sedimentation rate (107 mm/h). The cell blood count only revealed low levels of haemoglobin (8.26 g/dl). Human immunodeficiency virus and syphilis serologies were both negative. Biopsy specimens of the lesion revealed non-specific changes, revealing pseudoepiteliomatous hyperplasia, ulceration and acute inflammation. The bone biopsy showed extensive necrotic areas of bone and soft tissues, with lymphocytic exudate foci. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the head revealed bone destruction principally involving both the parietal bones, and parts of the frontal and occipital bones. No encephalic alterations were observed, but calcification of the soft tissues and sequestra were also present (Fig. 2). Streptococcus parasanguis was isolated from the skin culture, and Proteus mirabilis (sensitive to amoxicillin-clavulanic, levofloxacin and gentamicin) and Peptostreptococcus sp. (sensitive to amoxicillin-clavulanic, clindamycin and cloranfenicol) were identified in the cultures from the bone. Proteus mirabilis was also identified in the exudate. The patient declined any surgical treatment. A long-term treatment with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (1 g/12 h) and levofloxacin (500 mg/day) was prescribed based on the antibiotic sensitivity test, but after 6 months of the initial visit, the lesion remained unchanged.

Scalp ulcers are infrequent in dermatological patients, principally because of the rich blood supply to this area. Several previous reports have described them in Marjolin ulcer3, ulcerative carcinomas4, giant cell arteritis5, pyoderma gangrenosum6, trigeminal trophic syndrome7 and even cholangiocarcinoma8. Other differential diagnoses include viral, bacterial and mycotic infections as well as erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp. Although there are reports about acute osteomyelitis after scalp avulsion9, we have not identified any similar description of an ulcer of the scalp with subjacent chronic osteomyelitis discovered more than 50 years after the original trauma.

On the other hand, osteomyelitis of the head and neck is a case of rare occurrence. It usually results from bacterial infections, although fungi, parasites and viruses can also affect the bone and marrow. The management of osteomyelitis in the head has not been studied in detail, and the management could be different from other parts of the body due to the nature of the bones and the complex anatomy of the region. Chronic osteomyelitis in elderly people has been associated with performance of surgical procedures, dental extraction or poor dentition, and more commonly, has been associated with systemic disorders such as peripheral vascular disease and diabetes mellitus10. In a recent review of predisposing factors in 84 cases of head and neck osteomyelitis, contiguous infections (mainly chronic sinusitis) were the most frequent underlying cause in 33% of patients, followed by radiation, malignancy, diabetes, tuberculosis and odontogenic infections. An antecedent of trauma, as in our case, was identified in only 6% of patients1. Chowdri et al. confirmed that osteomyelitis was the third cause (11%) of nonhealing sinuses, and fistulous tracts of head and neck in 117 patients11. In their report, dental tracts (53%) and infected implants or bone grafts (20%) were the two main causes. Despite the fact that diabetes is related to osteomyelitis, this association is typical in foot ulcers. Therefore, we consider that in our case, the trauma is the main cause of the cranium osteomyelitis.

The clinical features, which are characteristically found in chronic osteomyelitis are usually milder than the acute variant, including pain, fever, pus and sequestra exudates through fistulae, indurations of soft tissues and pain and tenderness on bone palpation. X-ray tests and high-resolution CT are useful in the evaluation of cortical destruction, areas of sequestra/involucrum and for planning of the surgical treatment. A culture from the needle biopsy of infected tissue identifies the causal microorganisms, which is essential for diagnosis and treatment. Biopsy examinations of the overlaying skin were also very helpful in our case to rule out a subjacent carcinoma or inflammatory disease.

Although Staphylococcus aureus is by far the most commonly involved microorganism in osteomyelitis, many others have been isolated; including Proteus mirabilis and Peptostreptococcus sp., as in our case. Proteus mirabilis is a Gram negative bacterium that is a part of the normal flora of the human gastrointestinal tract. It commonly causes urinary infections, but it is a rare causal agent in osteomyelitis. Peptostreptococcus sp. are anaerobic organisms that are part of the normal flora of the skin and other mucocutaneous surfaces. They are one of the predominant anaerobic microorganisms reported in osteomyelitis12. Material isolated by swabbing an open sinus track can provide misleading results because the isolated bacteria could be non-pathogenic microorganisms colonising the site2. However, in our patient, Proteus mirabilis was identified in both, the exudate and the bone culture. The isolation of Streptococcus parasanguis in the skin culture seemed to represent a secondary skin infection.

It is accepted that the prognosis of chronic osteomyelitis principally depends on the surgical debridement, and appropriate antimicrobial therapy is adjunctive. The main factor that must be considered when a medical treatment is recommended is the sensitivity of the causal agent to the employed antibiotic. It has also been suggested that the method of antibiotic administration (oral vs. parenteral) does not have any impact on the rate of disease remission13. Our patient refused any surgical intervention. The oral antibiotic treatment improved the clinical appearance of the lesion in the first weeks, but the ulcer persisted with the same size even after 6 months from the initiation of the treatment.

In conclusion, we present a case of chronic osteomyelitis discovered decades after a probable scalp avulsion. Although the patient had acceptable medical support, nobody suspected the scalp affectation, because she always wore wigs. We want to highlight the importance of complete cutaneous evaluation when scalp osteomyelitis is suspected, including skin and bone biopsies to rule out the presence of other processes. On the other hand, every individual dermatologist must be aware of the possibility of scalp diseases in patients wearing wigs.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Prasad KC, Prasad SC, Mouli N, Agarwal S. Osteomyelitis in the head and neck. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007. 127:194–205.

3. Calikapan GT, Akan M, Karaca M, Aköz T. Marjolin ulcer of the scalp: intruder of a burn scar. J Craniofac Surg. 2008. 19:1020–1025.

4. Stojicic MT, Slavik EE, Acimovic GT, Jovanovic MD, Stojmirovic DM, Vujotic LD. Simultaneous surgical treatment of ulcer terebrans with intracranial propagation and acoustic neurinoma on the same side: a case report. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008. 61:e9–e11.

5. Campbell FA, Clark C, Holmes S. Scalp necrosis in temporal arteritis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003. 28:488–490.

6. Poenitz N, Tadler D, Klemke CD, Glorer E, Goerdt S. Ulceration of the scalp: a unique manifestation of pyoderma gangrenosum. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005. 3:113–116.

7. Kautz O, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Müller ML, Schempp CM. Trigeminal trophic syndrome with extensive ulceration following herpes zoster. Eur J Dermatol. 2009. 19:61–63.

8. Dogan G, Karincaoglu Y, Karincaoglu M, Aydin NE. Scalp ulcer as first sign of cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006. 7:387–389.

9. Furuno M, Sakakura M, Waga S. Spreading osteomyelitis of Vol 23, Suppl 3, 2011 S367 the skull following complete scalp avulsion: case report. No Shinkei Geka. 1983. 11:403–407.

11. Chowdri NA, Sheikh S, Gagloo MA, Parray FQ, Sheikh MA, Khan FA. Clinicopathological profile and surgical results of nonhealing sinuses and fistulous tracts of the head and neck region. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009. 67:2332–2336.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download