Abstract

Vandetanib (ZD6474, Zactima™) is a novel, orally available inhibitor of different intracellular signaling pathways involved in tumor growth, progression, and angiogenesis, including vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2, epidermal growth factor receptor, and rearranged during transfection tyrosine kinase activity. The most frequently reported adverse events attributed to vandetanib include diarrhea, elevated aminotransferase, asymptomatic corrected QC interval prolongation, and hypertension. In a few randomized, double-blinded studies, cutaneous adverse events including these general symptoms have been reported, but there are only a few reports on the photosensitivity reaction to vandetanib domestically as conducted by dermatologists. In this report, we describe two cases of photosensitivity reactions induced by vandetanib. After improvement with steroid and antihistamine, the photosensitivity reaction was redeveloped by sequential treatment with docetaxel.

Drug-related photosensitivity is well established as a valid clinical entity1,2, and is typically activated by exposure to either ultraviolet radiation or visible light. Many chemicals or drugs have the potential for inducing such phototoxic reactions3-5. Vandetanib is a multi-targeted kinase inhibitor that exhibits potent activity against the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2), the kinase insert domain-containing receptor and, to a lesser extent, the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and rearranged during transfection (RET) tyrosine kinase6,7.

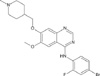

The chemical structure of vandetanib is shown in Fig. 17. It has increased progression-free survival in studies of patients with refractory non-small cell lung cancer and the drug is being evaluated as a treatment for other solid tumors, including breast, thyroid, prostate, brain, ovarian and renal cancers7,8. It is an orally administered, generally well-tolerated drug and the most common adverse effects include diarrhea, skin rash, hypertension and asymptomatic QTc prolongation6-8. Docetaxel (sanofi-aventis, Taxotere™) has emerged as one of the most important cytotoxic agents and has proven clinical efficacy against many cancers9,10. Docetaxel can cause skin reactions, but there are only a few report of photosensitivity reactions9,10. In this report, we describe two patients with cutaneous photosensitivity and subsequent pigmentation as related to treatment with vandetanib and docetaxel. The patients did not recover from the photosensitivity reaction using two cycles of docetaxel after the discontinuation of vandetanib.

A 67-year-old man was diagnosed with non-small cell lung cancer in November 2008. A systemic examination revealed left supuraclavicular, high mediastinal, paraaortic and left axillary lymph node metastasis, and the stage was determined to be T2N3M1. He was treated with gemcitabine and cisplatin. After four cycles of combined chemotherapy, he was enrolled in a phase II clinical trial with oral vandetanib (300 mg/d), which was administered in a phase II study (study # D4200C00077) that involved patients with non-small cell lung cancer at Gil Hospital, Inchen, Korea. One month after vandetanib administration, the patient visited our department with well-demarcated erythematous pruritic patches and plaques, and a slightly scaly appearance on the sun-exposed areas of the skin, including the neck, anterior chest and both dorsa of the hands (Fig. 2). The skin lesions occurred several days after the administration of vandetanib, and they gradually aggravated.

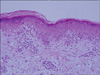

During the course of the clinical trial, the patient engaged in outdoor activities with adequate sun protection, but did not use sun-cream on the skin lesions. A biopsy specimen from his neck showed mild hyperkeratosis, dyskeratotic epidermal cells, vacuolar degeneration of the basal cells and pigmentary incontinence. Superficial perivascular edema and a dense lymphohistiocytic infiltration were present in the dermis (Fig. 3). A photo test and photo patch test were not performed because the patient declined further evaluations. He was treated with systemic steroid in combination with oral antihistamine and a moderately potent topical steroid. After discontinuation of vandetanib, the skin lesions improved in a month. His lung cancer then aggravated and he was treated with salvage chemotherapy that consisted of docetaxel (75 mg/m2). After his second intravenous course of docetaxel, the photosensitivity reaction redeveloped, and did not improve after discontinuation of docetaxel. He was prescribed oral systemic steroid and antihistamine with topical steroid, but the skin lesions did not improve (Fig. 4).

A 51-year-old man underwent vandetanib therapy for non-small lung cancer. He was diagnosed with non-small lung cancer in April 2009. After four cycles of combined chemotherapy (gemcitabine and cisplatin), he was enrolled in a phase II clinical trial with oral vandetanib (300 mg/d), which was administered in a phase II study (study # D4200C00077) that involved patients with non-small cell lung cancer at Gil hospital, Korea. Several days after the administration of vandetanib, he presented with erythematous pruritic papule and patches on the sun-exposed area of the skin, including the face, neck and both dorsa of the hands (Fig. 5A, B). A biopsy specimen from the forehead demonstrated hyperkeratotis, dyskeratotic epidermal cells, vacuolar degeneration of the basal cells and pigmentary incontinence (Fig. 5C). A photo test and a photo patch test were not performed. He was prescribed systemic steroids in combination with oral antihistamine and a topical steroid. The skin lesions improved in a month after discontinuation of vandetanib. After a second intravenous course of docetaxel (75 mg/m2) for salvage chemotherapy, the photosensitivity reaction redeveloped. Despite treatment with steroid and antihistamine, the skin lesions did not improve.

Drug-induced photosensitivity refers to the development of cutaneous disease as a result of the combined effects of a chemical and light1,2. It is caused by certain chemicals or drugs that are applied topically or taken systemically at the same time as exposure to ultraviolet radiation or visible light2,3. Exposure to either the chemical or the light alone is not sufficient to induce the disease; however, when photoactivation of the chemical occurs, one or more cutaneous manifestations may arise3,4.

The photosensitivity reactions may be more specifically categorized as being phototoxic or photoallergic in nature1,11. Phototoxicity is much more common than photoallergy3,4,12. Both reactions occur in the sun-exposed areas of the skin, including the face, neck and the dorsal surfaces of the hands and forearms, but the hair-bearing scalp, the postauricular and periorbital areas and the submental portion of the chin are usually spared1-4.

These reactions are not predictable11,13. They can occur in persons of any age, but are more common in adults than in children, possibly because adults are usually exposed to more medications and topical agents3,5,12. The degree of photosensitivity varies among individuals and not everyone will have the same impact from a photoreaction12,13.

Histologically, phototoxicity is characterized by dermal edema, dyskeratosis and necrosis of the keratinocytes3,14. In the case of a severe reaction, the necrosis is pan-epidermal1,4. Epidermal spongiosis with dermal edema and a mixed infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, macrophages and neutrophils may be present2,14. Photoallergic reaction is similar to contact dermatitis1,2,14. Epidermal spongiosis with a dermal lymphocytic infiltrate is a prominent feature1,4,14. The biopsy specimens showed dyskeratotic epidermal cells and vacuolar degeneration of basal cells, and the reactions had a relatively rapid onset, which meant that our cases were closer to phototoxicity. However, this was not certain as a photo and photo patch test were not performed because the patients refused further evaluation.

Vandetanib is an orally bioavailable inhibitor of VEGFR, EGFR and RET kinases6,7. Through anti-VEGFR-2 activity, it inhibits angiogenesis by decreasing the proliferation, migration and survival of endothelial cells7,8,15. Vandetanib was evaluated as a single agent in two phase I clinical trials that included patients with advanced refractory solid tumors15,16. In the first trial, one patient had a photosensitive rash with a 300 mg oral dose of vandetanib, but a more detailed description was not available15. In the second study, 13 out of of 18 patients developed rashes that included "acne" and photosensitivy16. Phase II clinical trials on vandetanib are currently underway for the treatment of a variety of tumors17,18. Photosensitivity was demonstrated in 23% of Japanese patients with non-small cell lung cancer in a phase II trial17.

Vandetanib is a low-molecular weight molecule with a polycyclic structure that contains unsaturated double bonds (Fig. 1)6,7. Photosensitizing chemicals usually have a low molecular weight (200 to 500 Da) and planar, tricylic or polycyclic configurations. They often contain heteroatoms that enable resonance stabilizations. Thus, vandetanib may be able to induce photosensitivity9,12,13.

Docetaxel is a semisynthetic taxane, which is a class of compounds that inhibit the mitotic spindle apparatus and stabilize tubulin polymers9,10. Docetaxel, either alone or in combination with other cytotoxic agents, has been effectively used in the treatment of several solid tumors, including non-small cell lung cancer and breast cancer10,19. The reported cutaneous reactions with docetaxel are usually mild and include erythrodysesthesia, maculopapular rash, erythema, desquamation, scleroderma-like and lupus-like lesions, alopecia and nail changes9,19. However, of all the reported effects of docetaxel, photosensitivity has only rarely been described previously.

In a previous report, the photosensitivity reaction was easily improved several weeks after the discontinuation of vandetanib20, but in our cases, the reaction was not resolved after sequential docetaxel treatment. This can be a direct toxic effect of docetaxel or an effect of polysorbate 80 (Tween 80), which is the vehicle for docetaxel9,10. However, there have been few reported photosensitivity reactions by docetaxel, so we believe the redevelopment of the skin lesions were due to vandetanib or the interaction between vandetanib and docetaxel. The mechanisms of interaction and etiology by which the photosensitivity redeveloped by docetaxel are obscure. Further evaluation may be required to determine the skin reaction caused by vandetanib and docetaxel.

In general, patients with acquired cutaneous photosensitivity should seek the care of dermatologists. We report here on two cases of redeveloped photosensitivity reaction related to vandetanib and docetaxel. As new targeted therapies are developed and introduced into the clinical setting, dermatologists will continue to play an important role in diagnosing and managing the novel cutaneous adverse effects of these targeted therapies.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 2

(A~D) Well-demarcated erythematous pruritic patches and plaques with a mild scaly appearance on the sun-exposed areas (case 1).

Fig. 3

The skin biopsy specimen from the neck showed mild hyperkeratosis, dyskeratotic epidermal cells, vacuolar degeneration of basal cells and pigmentary incontinence. Superficial perivascular edema and a dense lymphohistiocytic infiltration were present in the dermis (H&E, ×20, case 1).

References

1. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews' diseases of the skin. 2006. 10th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders;32–33.

2. Henry WL. Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, editors. Abnormal responses to ultraviolet radiation: photosensitivity induced by exogenous agents. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. 2008. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill;828–834.

3. Hölzle E, Lehmann P, Neumann N. Phototoxic and photoallergic reactions. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009. 7:643–649.

4. Stein KR, Scheinfeld NS. Drug-induced photoallergic and phototoxic reactions. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007. 6:431–443.

5. Racette AJ, Roenigk HH Jr, Hansen R, Mendelson D, Park A. Photoaging and phototoxicity from long-term voriconazole treatment in a 15-year-old girl. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005. 52:5 Suppl 1. S81–S85.

6. Heymach JV. ZD6474--clinical experience to date. Br J Cancer. 2005. 92:Suppl 1. S14–S20.

7. Sathornsumetee S, Rich JN. Vandetanib, a novel multitargeted kinase inhibitor, in cancer therapy. Drugs Today (Barc). 2006. 42:657–670.

8. Gridelli C, Maione P, Rossi A, Falanga M, Bareschino M, Schettino C, et al. New avenues for second-line treatment of metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009. 9:115–124.

9. Engels FK, Mathot RA, Verweij J. Alternative drug formulations of docetaxel: a review. Anticancer Drugs. 2007. 18:95–103.

10. Baker J, Ajani J, Scotté F, Winther D, Martin M, Aapro MS, et al. Docetaxel-related side effects and their management. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2009. 13:49–59.

12. Moore DE. Drug-induced cutaneous photosensitivity: incidence, mechanism, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 2002. 25:345–372.

13. González E, González S. Drug photosensitivity, idiopathic photodermatoses, and sunscreens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996. 35:871–885.

14. Elder D, Elenitsas R, Johnson B Jr, Murphy G, Xu Xl, Xu X. Lever's histopathology of the skin. 2009. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven;318–319.

15. Holden SN, Eckhardt SG, Basser R, de Boer R, Rischin D, Green M, et al. Clinical evaluation of ZD6474, an orally active inhibitor of VEGF and EGF receptor signaling, in patients with solid, malignant tumors. Ann Oncol. 2005. 16:1391–1397.

16. Tamura T, Minami H, Yamada Y, Yamamoto N, Shimoyama T, Murakami H, et al. A phase I dose-escalation study of ZD6474 in Japanese patients with solid, malignant tumors. J Thorac Oncol. 2006. 1:1002–1009.

17. Kiura K, Nakagawa K, Shinkai T, Eguchi K, Ohe Y, Yamamoto N, et al. A randomized, double-blind, phase IIa dose-finding study of Vandetanib (ZD6474) in Japanese patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2008. 3:386–393.

18. Miller KD, Trigo JM, Wheeler C, Barge A, Rowbottom J, Sledge G, et al. A multicenter phase II trial of ZD6474, a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 and epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with previously treated metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005. 11:3369–3376.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download