Abstract

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC), which frequently occurs in sun-exposed areas of the head and neck region, is the most common cutaneous malignancy. The nipple-areola complex (NAC) is an uncommon site for BCC to develop. BCCs in this region display more aggressive behavior and a greater potential to spread than when found in other anatomical sites. This paper outlines the case of 67-year-old female with a solitary asymptomatic black plaque on the right areola. The lesion was initially recognized as Paget's disease of the nipple by a general surgeon. However, the histopathological features showed a tumor mass of basaloid cells, a peripheral palisading arrangement and scattered pigment granules. Finally, the patient was diagnosed with pigmented BCC of the NAC and was referred to the department of dermatology. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography revealed the absence of distant metastasis. A wide excision was done. The lesion resolved without recurrence or metastasis during 14 months of follow-up.

Although basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common locally invasive tumor of the skin1, it rarely occurs on the nipple-areola complex (NAC). BCC occurring in this region is perceived to be more aggressive than that of other sites because higher metastasis rates to regional lymph nodes have been reported2. Men are affected more often than women. Since BCC lesions are clinically quite similar to other nipple diseases, they can easily be incorrectly diagnosed as Paget's disease, Bowen's disease, malignant melanoma, chronic dermatitis, and erosive adenomatosis3-5. We report on a rare case of pigmented BCC of the NAC occurring in a 67-year-old woman.

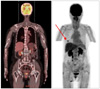

A 67-year-old woman presented with a solitary asymptomatic black plaque on the areola of the right breast, which had been present for about 30 years prior to presentation. Since the lesion was initially a small black papule without any subjective symptoms, the patient never had it evaluated or treated. Recently, it had become bigger in size and hyperkeratotic. At first, the patient visited the department of general surgery where, after a regular medical checkup including a mammography, the lesion was suspected to be breast cancer showing a periareolar microcalcification. Under the impression of malignancies such as Paget's disease, an ultrasonography-guided biopsy was conducted. However, pigmented BCC was revealed. Then, the patient was referred to the department of dermatology for further management. A physical examination revealed a 3×3 cm-sized, black plaque on the right NAC (Fig. 1). There were neither palpable masses of the breast nor axillary lymph node enlargement. The patient had been taking oral medications for cardiac arrhythmia and osteoporosis for about 1 year. The patient had no family history of skin cancer or a history of sunbathing, radiation, or arsenic exposure. An evaluation, including positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT), was done to determine if the tumor was metastatic. The focal hypermetabolic lesion thought to be the BCC was seen on the periareolar skin of the right breast but there was no abnormal 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose uptake, suggesting lymph node involvement or distant metastasis (Fig. 2).

The tumor including a 5 mm safe margin was widely excised. The postoperative histopathologic examination revealed basaloid cells forming cords and nests extending to the dermis with palisading peripheral nuclei and melanin pigment (Fig. 3). The basaloid cell nests were separated by clefts in the dermis and a clear resection margin was verified. However, there was no invasion of the underlying lactiferous ducts. No recurrence was noted during the 14-month follow-up.

BCC of the NAC is an uncommon human skin cancer2. After reviewing published literature from 1893 to 2008 (115 years), these authors identified only 33 cases of BCC of the NAC. Since Robinson and colleagues reported the first case of BCC of the NAC in a 60-year-old man in 18936, only 40 cases have been added to the English literature until now1,7. There are controversies over the incidence of BCC of the NAC. Benharroch and colleagues argued that the incidence of BCC of the NAC is higher than reported in the English literature8. However, only one case of BCC of the NAC was reported in Korean dermatological literature in 20069. BCC of the NAC in that case developed in a 73-year-old man. As exemplified by that case, BCC of the NAC affects men more often than women. However, the reason for the male predominance has not been explained clearly. The greater incidence of ultraviolet radiation exposure in this area in males has been a suggested reason10. In our case, a 67-year-old woman presented with a solitary asymptomatic black plaque on the right NAC. We were informed that the lesion started with a small black papule about 30 years ago. We could not know whether the lesion was a melanocytic nevus or not. There was no evidence from the postoperative examination to suggest that a melanocytic nevus was present. Although exposure to ultraviolet light is known to be one of the major risk factors for the development of BCC11, others have been elucidated, including family history of BCC, previous BCC at another site, and radiation. In addition, previous pigmented nevi should be examined as one of the risk factors for BCC.

There was a wide differential diagnosis to be considered in our case, including Paget's disease of the nipple, Bowen's disease, BCC and malignant melanoma. Our case was originally recognized as Paget's disease of the nipple. A mammography and an ultrasonography-guided biopsy were done to diagnose the lesion. Histopathologic findings showed proliferating nests of basaloid cells with a peripheral palisading arrangement of nuclei and an invasion of basaloid tumor cells into the dermis. The nests of tumor cells were separated from the stroma by a cleft. In addition, melanin pigment was present within solid nests of tumor cells and stromal macrophages. There were no aggressive features of BCC identified in histopathologic examination in our case.

Since there were no pathological subtype data on all cases, an overall assessment is impossible. But, of reported 40 cases, the majority of pathological subtypes were the superficial type, followed by the nodular or solid type. The pigmented type was described in three cases. Others have been reported on BCC of the NAC, including ulcerated, keratotic, infiltrative, fibroepithelioma and multicentric types. Pigmented BCC has been described as a clinical subtype of BCCs. Histologically, melanin can be found in the tumor mass and surrounding dermis12,13. Within the tumor mass, melanocytes are often hyperplastic and contain melanosomes. Melanin is preferably seen in the superficial component of the tumor. In the dermis, melanin is found primarily in melanophages, but small amounts may be lying free. Finally, hyperplastic melanocytes may be found in the overlying epidermis14. Because of their growth patterns and asymmetry of pigmentation, pigmented BCCs are included in the differential diagnosis of invasive melanoma. They may also be confused with other benign pigmented skin lesions15.

PET-CT revealed no signs of lymph node involvement or distant metastasis. The lesion was treated with a wide local excision so as to spare tissue. Because some authors maintain that BCC of the NAC has a higher metastatic potential than BCC at other sites16-18, minimally disfiguring surgery with concurrent sentinel node biopsy, such as Mohs' micrographic surgery or postoperative radiotherapy, might be recommended3,16,19. A higher-grade malignancy of BCC of the NAC can be explained by the rich angiolymphatic supply to the nipple, which may provide a direct route for the tumor to spread5. Another possible explanation may be found in the propensity of BCC of the nipple to involve underlying lactiferous ducts. Such invasion into deep soft tissue may enhance the chance of BCC of the nipple to metastasize3.

Herein, we report a rare case of pigmented BCC of the NAC that occurred in an elderly woman. This case shows that BCC of the breast should be included in the differential diagnosis from breast carcinomas. In addition, it is a given that this patient should be followed-up and investigated routinely for recurrence and metastases, because the lesion was treated with a tissue-sparing procedure and, as such, there is greater incidence.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Avci O, Pabuççuoğlu U, Koçdor MA, Unlü M, Akin C, Soyal C, et al. Basal cell carcinoma of the nipple - an unusual location in a male patient. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008. 6:130–132.

2. Ferguson MS, Nouraei SA, Davies BJ, McLean NR. Basal cell carcinoma of the nipple-areola complex. Dermatol Surg. 2009. 35:1771–1775.

3. Gupta C, Sheth D, Snower DP. Primary basal cell carcinoma of the nipple. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004. 128:792–793.

4. Davis AB, Patchefsky AS. Basal cell carcinoma of the nipple: case report and review of the literature. Cancer. 1977. 40:1780–1781.

5. Zhu YI, Ratner D. Basal cell carcinoma of the nipple: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2001. 27:971–974.

6. Robinson H. Rodent ulcer of the male breast. Trans Pathol Soc Lond. 1893. 44:147–148.

7. Sinha A, Langtry JA. Secondary intention healing following Mohs micrographic surgery for basal cell carcinoma of the nipple and areola. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011. 91:78–79.

8. Benharroch D, Geffen DB, Peiser J, Rosenberg L. Basal cell carcinoma of the male nipple. Case report and review of the literature. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1993. 19:137–139.

9. Kim WH, Park EJ, Kim CW, Kim KH, Kim KJ. A case of basal cell carcinoma of the nipple. Ann Dermatol. 2006. 18:100–104.

10. Sánchez-Carpintero I, Redondo P, Solano T. Basal cell carcinoma affecting the areola-nipple complex. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000. 105:1573.

12. Bleehen SS. Pigmented basal cell epithelioma. Light and electron microscopic studies on tumours and cell cultures. Br J Dermatol. 1975. 93:361–370.

13. Tezuka T, Ohkuma M, Hirose I. Melanosomes of pigmented basal cell epithelioma. Dermatologica. 1977. 154:14–22.

14. Maloney ME, Jones DB, Sexton FM. Pigmented basal cell carcinoma: investigation of 70 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992. 27:74–78.

15. Menzies SW, Westerhoff K, Rabinovitz H, Kopf AW, McCarthy WH, Katz B. Surface microscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2000. 136:1012–1016.

16. Shertz WT, Balogh K. Metastasizing basal cell carcinoma of the nipple. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986. 110:761–762.

19. Nouri K, Ballard CJ, Bouzari N, Saghari S. Basal cell carcinoma of the areola in a man. J Drugs Dermatol. 2005. 4:352–354.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download