Abstract

Syringocystadenoma papilliferum (SCAP) occurs singly or in association with other tumors. Although it is rare, the association of tubular apocrine adenoma (TAA) with SCAP in the background of nevus sebaceous (NS) on the scalp is well documented. However, the co-existence of these two tumors without background of NS has not been reported on the extremities. We report a case of SCAP associated with TAA on the calf without pre-existing NS in an adult.

Syringocystadenoma papilliferum (SCAP) is a benign adnexal tumor, thought to arise from either pleuripotential appendageal cells or apo-eccrine glands1,2. It may occur de novo in children but frequently arises from a head or neck organoid nevus3. It is rarely found on the trunk or limbs and occasionally coexists with other tumors. Recently, SCAP associated with tubular apocrine adenoma (TAA) in the background of nevus sebaceous (NS) on the scalp and facial area has been reported2-10. However, the co-existence of these two tumors without background of NS on a non-scalp area has rarely been reported. Herein, we report an unusual case of SCAP associated with TAA on the calf area without pre-existing NS, which occurred de novo in an adult.

A 59-year-old male presented with a 10-year history of a leg nodule, which had increased in size recently. Physical examination revealed a 1.3×1.2 cm sized itchy, erythematous and lobulated nodule on the left calf. There were erythematous and slightly depressed crusted lesions on the surface area (Fig. 1). The lesion was completely excised. Upon microscopic examination, the superficial component was characterized by cystic invaginations of infundibular epithelium, lined by two layers of glandular epithelium (tall columnar luminar cells and cuboidal basaloid basal cells), with papillary projections. The glandular epithelium had areas of decapitation secretion (Fig. 2).

The epidermis overlying the tumor showed crateriform squamous cell lesions with mild nuclear atypia and focal dyskeratosis. Around this crateriform lesion, irregular invasion of the dermis by uneven, jagged, blunt ended epidermal cell masses and strands was observed (Fig. 3). Immunohistochemical stains taken for this lesion revealed all negatives for p53, p63, and Ki-67. The deeper portion had variable sized tubular structures, surrounded by increased collagenous stroma. The tubules usually contained two layers of epithelial cells; the outer layer had flattened cells, and the inner layer had columnar cells with decapitation secretion (Fig. 4). The findings in the upper level of the lesion were interpreted as SCAP and those in the deeper level were TAA.

SCAP has been reported to arise frequently in association with NS or basal cell epithelioma3. However, it occasionally coexists with other tumors originating from skin appendageal cells. In a study of 126 SCAP cases, Fujita and Kobayashi reported that SCAP was most frequently associated with sebaceous nevus (40 cases), followed by basal cell epithelioma (13 cases), sebaceous epithelioma (4 cases), apocrine hydrocystadenoma (4 cases), trichoepithelioma (2 cases), and eccrine spiroadenoma (1 case)11.

The association of SCAP with TAA was firstly reported in 1979 by Civatte et al.4. Since then, several similar cases have been described in the literature with common features of occurrence on the scalp and associated with NS4-10. Fisher12 described TAA as a minor variant of SCAP due to a clinicopathological similarity. However, Umbert and Winkelmann13 suggested that TAA is an independent clinical entity, consisting of a benign appendage tumor of apocrine origin, associated with organoid nevus.

TAA and SCAP may show histopathological overlaps, with some lesions having features of both neoplasms (SCAP+TAA). Kazakov et al.14 confirmed a morphological overlap between TAA and SCAP and demonstrateed a lack of universally accepted diagnostic criteria even among experienced dermatopathologists and pathologists. In this study, interobserver variability occurred when there were epidermal acanthosis, papillomatosis, and connections of neoplastic tubules to the overlying epidermis and/or follicular infundibula as well as plasma cell infiltration. These features accounted for the morphological overlap between TAA and SCAP.

Furthermore, SCAP is considered a hamartoma that recapitulates the formation of the folliculo-apocrine unit14. In this regard, TAA is interpreted as a deeper dermal tubular component of SCAP, rather than a combination of TAA with hamartoma15,16.

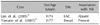

Cribier et al.2 reported that SCAP is the most common benign secondary tumor associated with NS. This is probably due to the presence of ectopic apocrine glands that are located in the deepest part of the NS, which can lead to either apocrine cysts or to SCAP. Thus, it is commonly located on the face and scalp. However, in our case there was no evidence of pre-existing NS upon microscopic examination. Only 2 cases of TAA associated with SCAP without NS of the scalp have been reported in the medical literature, and these cases are summarized in Table 1.

Our case demonstrates that SCAP with TAA can arise on non-scalp areas without a NS background in adults. Although the origin of SCAP and TAA and their relationships with follicular units need to be evaluated, we suggest that there can be SCAP lesions with TAA as a deeper component presenting on unusual sites.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 11.3×1.2 cm-sized itchy, errythematous, lobulated nodule with a partially crusted surface on the left calf area. |

| Fig. 2Whole-mounted view of the lesion: Tumor is composed of two histologically distinct parts. The upper part shows syringocystadenoma papilliferum and the lower part shows tubular apocrine adenoma (H&E, scanning view). |

| Fig. 3Findings of the upper section of the lesion. Cystic invagination lined by glandular epithelium with papillary projections. The cystic invagination is connected to the skin surface through the infundibular epithelium (H&E, A: ×40, B: ×100). |

References

1. Mammino JJ, Vidmar DA. Syringocystadenoma papilliferum. Int J Dermatol. 1991. 30:763–766.

2. Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000. 42:263–268.

3. Helwig EB, Hackney VC. Syringadenoma papilliferum; lesions with and without naevus sebaceous and basal cell carcinoma. AMA Arch Derm. 1955. 71:361–372.

4. Civatte J, Belaïch S, Lauret P. Tubular apocrine adenoma (4 cases) (author's transl). Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1979. 106:665–669.

6. Ansai S, Watanabe S, Aso K. A case of tubular apocrine adenoma with syringocystadenoma papilliferum. J Cutan Pathol. 1989. 16:230–236.

7. Yasuhara M. Typical but rare cases. 1989. Tokyo: Seishindou;22.

8. Ahn BK, Park YK, Kim YC. A case of tubular apocrine adenoma with syringocystadenoma papilliferum arising in nevus sebaceus. J Dermatol. 2004. 31:508–510.

9. Lee CK, Jang KT, Cho YS. Tubular apocrine adenoma with syringocystadenoma papilliferum arising from the external auditory canal. J Laryngol Otol. 2005. 119:1004–1006.

10. Kim MS, Lee JH, Lee WM, Son SJ. A case of tubular apocrine adenoma with syringocystadenoma papilliferum that developed in a nevus sebaceus. Ann Dermatol. 2010. 22:319–322.

11. Fujita M, Kobayashi M. Syringocystadenoma papilliferum associated with poroma folliculare. J Dermatol. 1986. 13:480–482.

14. Kazakov DV, Bisceglia M, Calonje E, Hantschke M, Kutzner H, Mentzel T, et al. Tubular adenoma and syringocystadenoma papilliferum: a reappraisal of their relationship. An interobserver study of a series, by a panel of dermatopathologists. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007. 29:256–263.

15. Requena L, Kiryu H, Ackerman AB. Requena L, Kiryu H, Ackerman AB, editors. Hamartomas, benign neoplasms. Neoplasms with apocrine differentiation. 1998. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven;75–563.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download