Abstract

Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS) is a neurocutaneous syndrome, characterized by the association of facial port-wine hemangiomas in the trigeminal nerve distribution area, with vascular malformation(s) of the brain (leptomeningeal angioma) with or without glaucoma. Herein, we reported Sturge-Weber syndrome in a 50-year-old man, who presented port-wine hemangiomas and epilepsy. In this case, the patient's epilepsy episodes from his first year of life had been ignored and separated from the entity of SWS by his physicians, which led to delayed treatment. This case illustrates the importance of careful examination of patients of any age with hemangiomas in the trigeminal nerve with concomitant episodes of epilepsy. In such cases, there should be yearly neuroimaging screenings to guaranteed early interdisciplinary interventions from the time of definite diagnosis.

Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS, also called encephalofacial or encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis) is a neurocutaneous syndrome, characterized by the association of facial port-wine hemangiomas in the trigeminal nerve distribution area, with a vascular malformation of the brain (leptomeningeal angioma) with or without glaucoma1. Although facial hemangiomas in SWS are typical at birth, they are prone to misdiagnosis as haplo-hemangiomas, if other concomitant symptoms are not considered together, which may lead to delayed diagnosis and intervention.

This 50-year-old man was admitted to Daping Hospital for evaluation and aesthetic treatment of left facial port-wine nodules, which presented as port-wine stains at birth. With his increasing age, the stains darkened in color and became raised and thickened. His family complained of his episodes of epilepsy, which started during the first year of his life. He had been taking phenobarbital to control the epilepsy; however, the epilepsy became more intense.

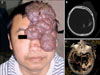

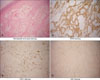

On examination, well-demarcated cutaneous port-wine macular stains and vascular nodules were observed on the left side of the face that followed the trigeminal nerve distribution area (Fig. 1A). Hemiatrophy of his right leg and failure of closing together of the right fingers were observed. There was no evidence for either contralateral hemiplegia or intellectual disability. A skin biopsy from one of the angiomatous nodules showed a cavernous hemangioma pattern, and dilated and ectatic thin-walled vessels in the superficial dermis were observed.

Immunohistochemistry results (immunoperoxidase method) showed CD34(+), CD31(+), and Ki67(-) (Fig. 2). There were no abnormalities related to his right eye, and his left visual field was blocked by the port-wine nodules. Radiologically, homolateral cerebral atrophy and subcortical calcifications in the left occipital lobe and leptomeningeal vascular angiomas located in the parietooccipital area were indicated on computed tomographic (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and cerebral CT angiography, respectively (Fig. 1B, C). The diagnosis of SWS was made according to the clinical and neuroimaging characteristics. His left superficial temporal artery was ligated and the port-wine nodules were excised by neurologic surgeons. Subsequently, his episodes of epilepsy ceased.

The incidence of SWS is three percent in patients with a facial port-wine hemangioma2. There is an increased risk of SWS with involvement of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve. Facial port-wine hemangiomas, whether or not associated with SWS, usually have a sharp midline demarcation, although some extension over the midline has been observed3.

Computed tomography angiography, MRI, and CT are the best modalities to demonstrate the vascular malformation, the impaired cerebral venous drainage, and the atrophy of one hemisphere and calcifications, respectively. Atrophy and calcifications are considered to be an indirect consequence of chronic ischemia of the cortex due to vascular stasis in the area of leptomeningeal angioma. Recent advances in neuroimaging have provided important insights into the progression of neurologic injury that occurs as a result of impaired blood flow. Important limitations exist, however, as currently the early diagnosis and exclusion of SWS is impaired by the poor sensitivity of imaging in the newborn period and early infancy1. Epilepsy, hemiparesis, mental retardation, and ocular problems were the most frequent and severe features of patients with SWS. Limited intelligence and social skills, poor aesthetic appearance, and epilepsy complicate the integration of the patients. The clinical severity of this case is not the originality of our paper, because no relationship was observed between the size of the facial port-wine hemangiomas and the severity of the brain lesion4,5. Symptoms depend upon the extent and location of the venous dysplasia. Early onset of epilepsy and poor response to medical treatment, bilateral cerebral involvement, and unilateral severe lesions are indicative of a poor prognosis4. Early surgery is more likely to improve developmental outcome, although, in some instances, therapies aimed at obliterating port-wine hemangiomas to minimize cosmetic blemishes may worsen blood stasis within the brain and potentially exacerbate neurologic symptoms6,7. Considering the complications that may be emerged during the treatment, especially the patient's own possible apprehension of the condition, it is imperative that the diagnostician and surgeon have thorough knowledge of this syndrome.

In this case, the episodes of epilepsy from birth had been ignored and separated from SWS by his physicians, which led to delayed treatments for nearly 50 years. As we said above, the clinical severity does not represent the originality of this case. Rather, this case illustrates the importance of careful examination of patients of any age with hemangiomas in the trigeminal nerve with concomitant episodes of epilepsy. Such patients require yearly neuroimaging examinations. Thorough knowledge of this syndrome and high awareness of this entity may lead to earlier diagnosis and more timely and appropriate medical interventions.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Comi AM. Update on Sturge-Weber syndrome: diagnosis, treatment, quantitative measures, and controversies. Lymphat Res Biol. 2007. 5:257–264.

2. Hennedige AA, Quaba AA, Al-Nakib K. Sturge-Weber syndrome and dermatomal facial port-wine stains: incidence, association with glaucoma, and pulsed tunable dye laser treatment effectiveness. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008. 121:1173–1180.

4. Pascual-Castroviejo I, Pascual-Pascual SI, Velazquez-Fragua R, Viaño J. Sturge-Weber syndrome: study of 55 patients. Can J Neurol Sci. 2008. 35:301–307.

5. Rodofile C, Grees SA, Valle LE, Martino G. Sturge-Weber syndrome. Report of a case with poor dermatological manifestations. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2011. 109:e42–e45.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download