Abstract

Histiocytic skin disorders are usually classified as either Langerhans' cell histiocytosis (LCH) or non LCH, based on the pathology. Benign cephalic histiocytosis (BCH) is a rare type of non-Langerhans histiocytitic disorder and is characterized by self-healing multiple small eruptions of yellow to red-brown papules on the face and upper trunk. Histologic features of this disorder show dermal proliferation of histiocytes that have intracytoplasmic comma-shaped bodies, coated vesicles and desmosome-like structures. In this study, we report on a 7-month-old boy who contained small yellow-red papules on his face that spread to his upper trunk. The clinical and histologic features in this patient were consistent with BCH.

Benign cephalic histiocytosis (BCH) is a rare, benign non-Langerhans histiocytitic disorder of infants and young children, and was first described by Gianotti et al. in 19711. This disorder is characterized by a self-healing, asymptomatic and multiple small eruptions of yellow to red-brown papules, which develops initially on the head and neck. Histological studies have shown that dermal proliferation of histiocytes, which have intracytoplasmic comma-shaped bodies, coated vesicles and desmosome-like structure, occurs with this disorder2. There have been reports showing that BCH may have overlapping clinical and histologic features with some other non-Langerhans histiocytitic disorders, including juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) and generalized eruptive histiocytoma (GEH)3. Here, we describe a 7-month-old boy that had clinicopathologic findings consistent with the diagnosis of BCH.

A 7-month-old white boy was referred to our department with small discrete, asymptomatic, yellow-red papules, which were first observed on his face at 1 month. The number of papules gradually increased over the following weeks and spread to his upper trunk and upper arms. He was otherwise healthy and developmentally normal. Both his weight and height were at the 50th percentile. His parents were not consanguineous and the family history was unremarkable. Clinical examination at the time of presentation demonstrated multiple, scattered yellow-red monomorphic papules that were 2 to 5 mm over the face, upper trunk and upper limbs (Fig. 1, 2). Mucous membranes, palms, soles and teeth were normal. He had no organomegaly or lymphadenopathy. Neurodevelopmental and ophthalmic examinations were normal.

In the routine blood test, the haematologic and biochemical results were normal. Serum lipid screening (cholesterol, triglycerides, High-density lipoprotein (HDL)- and low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol), IgA, IgG, IgM, serum protein electrophoresis and syphilis serology were all normal or negative. X-ray screening of skeletal system showed no bony defects. An upper abdominal ultrasonography was interpreted to be normal.

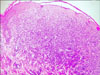

Histological examination of the biopsy specimen taken from a lesion on the left shoulder showed a normal epidermis and sufficient proliferation of large, pleomorphic epitheliod histiocytic cells with large cytoplasm within the upper- and mid-dermis without epidermotropism. Mitotic figures, multinucleated giant cells and cytoplasmic lipids were absent. There was an interstitial infiltration of moderate numbers of lymphocytes and scattered eosinophils (Fig. 3). In the immunohistochemistry analysis, the cells were stained positive for CD68, but negative for the S100 protein and CD1a (Fig. 4). According to the clinicopathologic findings, the disease was diagnosed as benign cephalic histiocytosis, a type of non-Langerhans cell histiocytic disorder.

Three months after his initial visit, none of the skin lesions had regressed and new lesions developed on the upper trunk and upper limbs.

BCH is a rare non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis of unknown etiology that is presented as a self-healing eruption in the head and neck2. Since the initial description of this disorder by Gianotti et al. there have been 42 reported cases in various races in the English language literature2,4,5. The clinical findings are asymptomatic, macules and papules that are 1~8 mm in diameter with colors ranging from yellow to red brown, which first appear on the upper half of the body, mainly on the face and neck. Lesions may subsequently extent to the upper and lower extremity, and buttocks. Consistent with other reported cases, our patient had multiple, 2 to 5 mm yellow-red monomorphic papules that first appeared on the face and later spread onto the upper part of the body and upper extremities. Mucous membranes, palms, soles, and visceral organs have not been reported to be involved in this disease6-9. The lesions appear at ages ranging from 2 to 66 months (average 15 months). In approximately 50% of cases, the patients are younger than 6 months. Males and females are affected equally. Spontaneous regression of lesions begins on an average between 8 to 48 months and complete regression occurs on an average at 50 months, leaving hyperpigmented macules, but not scars2. Unfortunately, in our case, we only did a follow-up after 3 months; therefore, it was impossible to see regression of the lesions. Although systemic disease has not been associated with BCH, two articles have reported that BCH was associated with diabetes insipidus or insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus10,11. We did not find any association with other diseases in our case.

The histopathological features show well-circumscribed histiocytic infiltrates in the superficial to mid-reticular dermis. Cells were characterized by the presence of polymorphic nuclei, pale chromatin and abundant cytoplasm without cytoplasmic lipids. There are also inflammatory infiltrates composed of lymphocytes and rarely eosinophils. Although older lesions may contain giant cells, Touton giant cells or foam cells are not present3. Electron microscopy showed worm-shaped or comma-shaped bodies in the cytoplasm of 5~30% of the histiocytes. In contrast with Langerhans' cell histiocytosis (LCH), Birbeck granules are absent6. Immunohistochemical staining of lesional cells demonstrates positive staining for macrophage/histiocytic markers, including factor XIIIa and CD68, whereas they remain negative for Langerhans markers, including S100 protein and CD1a12.

BCH must primarily be differentiated from micronodular form of JXG and GEH6,8. Furthermore, LCH, plane warts, urticaria pigmentosa, lichenoid sarcoidosis and multiple Spitz nevi can be confused with BCH. Plane wart, Spitz nevi, urticaria pigmentosa can be distinguished by histologic examination. Lesions of JXG are not usually limited to the head and neck, but rather are more widely distributed over the entire body. In addition, extracutaneous involvement occurs most significantly in the eyes. Histologic examination shows foamy cells and Touton giant cells8,9. GEH is more common in adults, with a more extensive distribution of lesions and occasional mucosal involvement. The histologic appearance may be similar to BCH13,14. LCH has more widespread skin and visceral organ involvement and are positive for S100 and CD1a. Ultrastructural studies also showed the presence of Birbeck granules in LCH9.

Recent studies and case reports have indicated that BCH may have overlapping clinical and histologic features with JXG and GEH. Lesions of BCH was shown to transform into JXG in 2 cases15,16. Sidwell et al. reported an infant with a congenital form of non-LCH with clinical and histologic features of both disseminated JXG and BCH8. A case of GEH was also reported many years after complete regression of BCH17. In addition, in a blinded histological study by Gianotti et al, 50% of BCH cases could not be definitely distinguished form GEH and early nonxanthomatous JXG12. It has been suggested that BCH represents an abortive form of JXG rather than a separate entity16,18. The occurrence of BCH as a localized form of GEH in children was rarely reported13,19. The relationship of BCH with JXG and GEH is still not clear. Therefore, some authors have claimed that BCH, JXG and GEH belong to the same clinical entity. As a result, further research and data accumulation of cases are required to explain the relationship and pathogenesis between all of the non-Langerhans histiocytosis.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Gianotti F, Caputo R, Ermacora E. Singular "infantile histiocytosis with cells with intracytoplasmic vermiform particles". Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1971. 78:232–233.

2. Jih DM, Salcedo SL, Jaworsky C. Benign cephalic histiocytosis: a case report and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002. 47:908–913.

3. Zelger BW, Sidoroff A, Orchard G, Cerio R. Non-Langerhans cell histiocytoses. A new unifying concept. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996. 18:490–504.

4. Dadzie O, Hopster D, Cerio R, Wakeel R. Benign cephalic histiocytosis in a British-African child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005. 22:444–446.

5. Hasegawa S, Deguchi M, Chiba-Okada S, Aiba S. Japanese case of benign cephalic histiocytosis. J Dermatol. 2009. 36:69–71.

6. Baler JS, DiGregorio FM, Hashimoto K. Facial papules in a child. Benign cephalic histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 1995. 131:610–611.

7. Gianotti F, Caputo R, Ermacora E, Gianni E. Benign cephalic histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 1986. 122:1038–1043.

8. Sidwell RU, Francis N, Slater DN, Mayou SC. Is disseminated juvenile xanthogranulomatosis benign cephalic histiocytosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005. 22:40–43.

9. Watabe H, Soma Y, Matsutani Y, Baba T, Mizoguchi M. Case 2: benign cephalic histiocytosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002. 27:341–342.

10. Saez-De-Ocariz M, Lopez-Corella E, Duran-McKinster C, Orozco-Covarrubias L, Ruiz-Maldonado R. Benign cephalic histiocytosis preceding the development of insulindependent diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006. 23:101–102.

11. Weston WL, Travers SH, Mierau GW, Heasley D, Fitzpatrick J. Benign cephalic histiocytosis with diabetes insipidus. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000. 17:296–298.

12. Gianotti R, Alessi E, Caputo R. Benign cephalic histiocytosis: a distinct entity or a part of a wide spectrum of histiocytic proliferative disorders of children? A histopathological study. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993. 15:315–319.

13. Caputo R, Ermacora E, Gelmetti C, Berti E, Gianni E, Nigro A. Generalized eruptive histiocytoma in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987. 17:449–454.

14. Winkelmann RK, Kossard S, Fraga S. Eruptive histiocytoma of childhood. Arch Dermatol. 1980. 116:565–570.

15. Rodriguez-Jurado R, Duran-McKinster C, Ruiz-Maldonado R. Benign cephalic histiocytosis progressing into juvenile xanthogranuloma: a non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis transforming under the influence of a virus? Am J Dermatopathol. 2000. 22:70–74.

16. Zelger BG, Zelger B, Steiner H, Mikuz G. Solitary giant xanthogranuloma and benign cephalic histiocytosis--variants of juvenile xanthogranuloma. Br J Dermatol. 1995. 133:598–604.

17. Aliaga A, Alegre VA, Hernández M, Febrer MI, Martinez A, Portea JM. Benign cephalic histiocytosis vs generalized eruptive histiocytoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1989. 16:293–296.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download