Abstract

Background

Narrowband UVB (NBUVB) is currently used to treat early mycosis fungoides (MF). There are a number of reports on the efficacy and safety of NBUVB in Caucasians, but little data is available for Asians.

Objective

This study was designed to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of NBUVB for early stage MF in Korean patients.

Methods

We enrolled 14 patients (12 men, 2 women; age range, 10~64 years) with clinically and histologically proven MF. Three patients were stage IA, and the others were stage IB. The patients received NBUVB phototherapy three times a week. The starting dose was 70% of the minimal erythema dose and was increased in 20 percent increments if the previous treatment did not cause erythema. Clinical response, total number of treatments, total cumulative dose, duration of remission and side effects were investigated.

Results

Eleven of 14 patients (78.6%) achieved complete remission within a mean of 15.36±5.71 weeks (range, 5~27 weeks), 31.0±7.4 treatments (range, 16~39 treatments) and a mean cumulative UVB dose of 31.31±12.16 J/cm2 (range, 11.4~46.8 J/cm2). Three of the 14 patients (21.4%) achieved a partial remission. After discontinuation of treatment, 6 of 11 patients (54.5%) with complete remission relapsed after a mean of 8.5±4.09 months. No serious adverse effects were observed except for hyperpigmentation (7/14, 50%).

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. MF, which has been termed the "great imitator", presents with a variety of clinical features and nonspecific histological findings, especially in early lesions1-3. According to its natural course and prognosis, MF is classified into early (stage IA, IB and IIA) and advanced (stage IIB, III and IV) stages. Early MF presents as a variety of patches and plaques without internal involvement, and may progress to a more advanced stage. Currently, the treatment of early-stage MF includes topical agents (corticosteroid, nitrogen mustards, carmustine and bexarotene), electron beam therapy and phototherapy (oral psoralen plus UVA, broadband UVB, narrowband UVB, UVA-1, excimer laser, photodynamic therapy). Among these therapeutic options, narrowband UVB (NBUVB) is safe and convenient in comparison to the other treatments. To date, a number of reports have shown that NBUVB phototherapy is effective for early stage MF. However, these studies typically involve patients in Western populations, and there are a lack of studies on the therapeutic effects of NBUVB on early MF in Asian patients, who have a different skin phototype. In this study, we analyzed the efficacy and safety of NBUVB in Korean patients with early-stage MF.

Fourteen patients, who were clinically and histologically diagnosed with MF between June 2007 and April 2010, were enrolled in this study after providing informed consent for treatment. According to the TNM staging4 proposed in 2007 by the International Society of Cutaneous Lymphoma/European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer, all patients were classified as stage IA or IB. All patients were treated with NBUVB phototherapy alone without being combined with topical steroid or topical chemotherapy during the course of the study.

We excluded any patient who had a history of photosensitivity disease or who was being treated with photosensitizing medication. Six patients had received a previous treatment other than NBUVB, such as topical steroid or psoralen UVA (PUVA), but they did not receive any treatment at least 6 months prior to starting NBUVB.

The NBUVB irradiation was performed in a UV7001K phototherapy cabinet (Waldmann, Villingen-Schwenningen, Germany) equipped with TL-01 lamps (Philips Lighting BV, Roosendaal, Netherlands) emitting NBUVB wavelengths between 311 and 313 nm. Each patient's minimal erythema dose (MED) was determined before the start of irradiation. The initial treatment dose was 70% of a patient's individual MED, with subsequent incremental increases of 20% if the previous treatment caused no or slight erythema. Most patients received irradiation 3 times weekly, continuing treatment until there was more than 95% clearing of the patient's skin lesions.

Responses to phototherapy were clinically assessed by two independent dermatologists using clinical photographs with the same digital camera (α350, Sony, Tokyo, Japan) in the same position under controlled lighting conditions at each follow-up visit. Clinical responses to treatment were classified as complete response (>95% clearance of lesions), partial response (50~95% clearance), and no response (<50% clearance). Any adverse effects such as erythema, hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, pruritus, and xerosis were also assessed at each visit.

Of the 14 patients, 12 were male and 2 were female with ages ranging from 10 to 64 years (mean, 32.5±17.1 years), while the mean duration of skin lesions before diagnosis was 47.2±57.0 months. All patients had Fitzpatrick skin types ranging from III to V (4 for III, 8 for IV and 2 for V, respectively). Six patients (42.9%) complained of pruritus, but the others (57.1%) were asymptomatic. All of the patients presented clinically with patches and papules, but none of them had plaques: 12 presented with patches and the other 2 with papules. Three of the 14 patients were stage IA (21.4%), the other 11 (78.6%) were stage IB.

Of the 14 treated patients, complete and partial responses were observed in 11 (78.6%) and 3 (21.4%) patients, respectively (Fig. 1, 2). The mean number of treatments in patients with a complete response was 31.0±7.4 within a mean time of 15.4±5.71 weeks (range, 5~27 weeks) and the cumulative dose was 31.3±12.2 J/cm2 (range, 15.3~46.8 J/cm2). Six (54.5%) of the 11 patients with complete response recurred after a mean follow-up period of 8.5±4.1 months (range, 5~25 months). A complete response according to the stage was achieved in 66.7% and 81.8% in stage IA and IB, respectively. For stage IA, the mean number of treatments was 23.3±4.5, and the cumulative dose was 23.7±7.0 J/cm2, whereas, in stage IB, the mean number of treatments was 31.4±7.3, and the cumulative dose was 32.7±11.2 J/cm2.

MF, particularly in its early stages, may clinically and histologically mimic benign inflammatory dermatoses including atopic dermatitis, psoriasis and seborrheic dermatitis, thus making it difficult to diagnose. Patients with early MF commonly have an indolent and chronic course with recurrence, but rarely progress to more aggressive course if not treated in time. Therefore, appropriate therapeutic decision and treatment are important in terms of prognostic significance.

Selection of treatment is often determined by various factors including age, stage, extent of involvement and experience of physician. Since a variety of reviews and outcomeshave been reported to try and provide a more rational criteria for the management of MF, skin directed therapy (SDT) is currently recognized as the optimal treatment for early-stage MF5-7. SDT includes topical corticosteroids, topical chemotherapy (nitrogen mustard, carmustine), topical bexarotene, phototherapy and electron beam therapy. Of these treatments, topical therapies, which have been used for patients with limited patch lesions, include potential adverse events (telangiectasia, allergic contact dermatitis, skin atrophy and skin cancer, etc.) and are unsuitable for controlling extensive lesions. Electron beam therapy is also associated with several side effects including exfoliation, alopecia, telangiectasia and pigmentation. In patients with more widespread lesions, or in those for whom topical treatments have been ineffective, phototherapy is suitable. Since PUVA was firstly reported as phototherapy for MF in 1976 by Gilchrest et al.8, phototherapeutic modalities with various light sources have been applied. To date, phototherapeutic options for MF published in the literatures include PUVA, NBUVB, broadband UVB (BBUVB), UVA-1, photodynamic therapy and excimer laser. Of the various phototherapeutic options, PUVA and NBUVB have been used as the most common phototherapies for patch and plaque MF. In addition to NBUVB and PUVA, photodynamic therapy, excimer laser, and UVA-1 have been studied in small case series9-11. However, the efficacy and safety of these modalities have not been determined, and these treatments limited due to their relatively narrow therapeutic extent.

The advantages of PUVA over NBUVB, including long-term therapeutic response, deeper penetration into the skin, and possibility of once-a-month maintenance, have been reported in some studies. However, PUVA has side effects including nausea, headache, light-headedness, the need for sun protection and higher risk for skin cancer. There are some studies comparing efficacy and safety of NBUVB and PUVA in patients with early stage MF12-15. Most of these comparative studies have shown that both NBUVB and PUVA achieve similar results in terms of complete remission rates and the mean relapse-free interval.

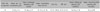

Recently, NBUVB, which has a lower incidence of adverse events and a similar efficacy to other photodynamic therapies, has become the treatment-of-choice for early stage MF. The first report of NBUVB in early MF was published by Hofer et al.16 in 1999. In this study, complete remission in 5 out of 6 patients was achieved after a mean of 20 treatments and 17.2 J/cm2 cumulative doses, and relapses were reported in all patients within a mean of 6 months after discontinuation of treatment. Since then, the efficacy of NBUVB for treating early stage MF has been reviewed through a variety of protocols12,15,17-24 (Table 5). However, previous clinical reports have, for the most part, been conducted in Caucasians, while there has generally been little research on Asians. Some authors have also found that patients with darker skin types are less responsive to NBUVB phototherapy18. These resistances to phototherapy are associated with the photoprotective function of melanin, which can absorb radiation from various spectrums. However, Kural et al.25 suggested that the stage of MF is more crucial than Fitzpatrick skin phototype in determining the response to NBUVB. In our study, all patients were assessed for therapeutic response according to Fitzpatrick skin phototype and stage, in order to investigate the efficacy of NBUVB in higher skin phototypes. We found that a higher Fitzpatrick skin phototype was significantly less responsive to phototherapy. Furthermore, there are no significant difference in therapeutic between stage IA and IB. However, it is difficult to evaluate accurately the response rate according to stage because of small subjects of stage IA and various locations of the lesions. Actually, only stage IA patient showing partial response after NBUVB phototherapy presented patch lesion at submammary area, which may be the possibility of insufficient irradiation. Moreover, patients with higher stages required more treatments and a higher cumulative dose to induce complete remission.

Although the mechanism for NBUVB phototherapy in MF has not yet been established, the therapeutic mechanism may involve changes in cell cycle kinetics, or alterations in cytokine expression and immunomodulation15. Several studies have reported that NBUVB induces an increase in expression of IL-2, IL-6 and TNF-α by human keratinocytes and a decrease in the allo-activating and antigen-presenting capacity of Langerhans cells26,27. Additionally, NBUVB may suppress the neoplastic proliferation of clonal T-cells and serve as an up-regulator of the immune system28. We also suggest that NBUVB may directly induce apoptosis of atypical lymphocytes, which confined to epidermis and papillary dermis.

Assessment of the response to phototherapy in MF is based on clinical, histopathological and molecular findings. Especially, clinical assessment is commonly used and is easy to apply, but regular inspection and experience of physician is required. Gökdemir et al.22 found that clinical remission correlates with histopathological improvement, especially for patch lesions. On the other hand, Dereure et al.29 suggested that clinically defined complete remission does not mean a complete histological response. It has also been demonstrated that a deficient histological response and the presence of a dominant T cell clone are related to a high rate of recurrences.

Whether maintenance treatment is needed for longer duration of remission is still debatable. Some studies have indicated that maintenance treatment after complete remission may prolong relapse-free intervals or may reduce relapse12,20. On the other hand, some authors have advocated that maintenance treatment should be stopped completely following the first complete remission, because ongoing treatment may increase the risk of skin cancer or lead to progression to the higher stage of MF due to UVB-induced DNA damage21,29.

The acute side effects of NBUVB include erythema, edema, blistering, pruritus, and reactivation of herpes simplex virus, but these usually resolve within several days30. Although previous studies have described a possibility of photoaging and carcinogenesis in association with NBUVB, there is still no evidence that this occurs. There have also been some reports that NBUVB is much safer than PUVA17,18,31. In our study, hyperpigmentation (50%) was more common due to the higher skin phototype compared to other studies, but no significant side effects, aside from mild erythema, were observed. Moreover, we found that all patients showing hyperpigmentation after NBUVB phototherapy achieved a complete response. We also suggest that it might play a role of predictive marker of response to NBUVB phototherapy in Asians.

The prognosis for patients with early stage mycosis fungoides is favorable. In fact, the survival of patients with stage IA or IB MF is not affected by the disease, but management of early MF is important in term of life quality and prevention of progression.

In our experience, the treatment for early MF should be selected according to clinical presentations (patch or plaque), regardless of TNM stage of MF. Especially, patients with clinically defined lesions of patches and thin plaques are highly responsive to NBUVB phototherapy. Additionally, we suggest that PUVA is suitable for patients who have clinically thick plaques or who are unresponsive to NBUVB. In conclusion, NBUVB phototherapy is an effective and safe treatment for early stage MF in Asians. However, our study is limited because we did not perform a histopathological assessment after treatment. Further prospective studies are still necessary to determine the therapeutic effects and side effects of NBUVB phototherapy in Koreans.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1(A) Patch-stage mycosis fungoides with erythematous patches on the trunk. (B) Complete clinical remission after 36 treatments of narrowband UVB (case 6). |

| Fig. 2(A) Patch-stage mycosis fungoides with erythematous patches on whole dody. (B) Complete clinical remission with only residual hyperpigmentation after 37 treatments of narrowband UVB (case 9). |

References

1. Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, Vonderheid E, Haeffner AC, Stevens S, et al. International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005. 53:1053–1063.

2. Zackheim HS, McCalmont TH. Mycosis fungoides: the great imitator. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002. 47:914–918.

3. Nashan D, Faulhaber D, Ständer S, Luger TA, Stadler R. Mycosis fungoides: a dermatological masquerader. Br J Dermatol. 2007. 156:1–10.

4. Olsen E, Vonderheid E, Pimpinelli N, Willemze R, Kim Y, Knobler R, et al. ISCL/EORTC. Revisions to the staging and classification of mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the cutaneous lymphoma task force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007. 110:1713–1722.

5. Kim EJ, Hess S, Richardson SK, Newton S, Showe LC, Benoit BM, et al. Immunopathogenesis and therapy of cutaneous T cell lymphoma. J Clin Invest. 2005. 115:798–812.

6. Trautinger F, Knobler R, Willemze R, Peris K, Stadler R, Laroche L, et al. EORTC consensus recommendations for the treatment of mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome. Eur J Cancer. 2006. 42:1014–1030.

7. Willemze R, Dreyling M. ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Primary cutaneous lymphoma: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2009. 20:Suppl 4. 115–118.

8. Gilchrest BA, Parrish JA, Tanenbaum L, Haynes HA, Fitzpatrick TB. Oral methoxsalen photochemotherapy of mycosis fungoides. Cancer. 1976. 38:683–689.

9. Zane C, Venturini M, Sala R, Calzavara-Pinton P. Photodynamic therapy with methylaminolevulinate as a valuable treatment option for unilesional cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2006. 22:254–258.

10. Passeron T, Zakaria W, Ostovari N, Perrin C, Larrouy JC, Lacour JP, et al. Efficacy of the 308-nm excimer laser in the treatment of mycosis fungoides. Arch Dermatol. 2004. 140:1291–1293.

11. Plettenberg H, Stege H, Megahed M, Ruzicka T, Hosokawa Y, Tsuji T, et al. Ultraviolet A1 (340-400 nm) phototherapy for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999. 41:47–50.

12. Diederen PV, van Weelden H, Sanders CJ, Toonstra J, van Vloten WA. Narrowband UVB and psoralen-UVA in the treatment of early-stage mycosis fungoides: a retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003. 48:215–219.

13. El-Mofty M, El-Darouty M, Salonas M, Bosseila M, Sobeih S, Leheta T, et al. Narrow band UVB (311 nm), psoralen UVB (311 nm) and PUVA therapy in the treatment of early-stage mycosis fungoides: a right-left comparative study. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2005. 21:281–286.

14. Ahmad K, Rogers S, McNicholas PD, Collins P. Narrowband UVB and PUVA in the treatment of mycosis fungoides: a retrospective study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007. 87:413–417.

15. Ponte P, Serrão V, Apetato M. Efficacy of narrowband UVB vs. PUVA in patients with early-stage mycosis fungoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010. 24:716–721.

16. Hofer A, Cerroni L, Kerl H, Wolf P. Narrowband (311-nm) UV-B therapy for small plaque parapsoriasis and early-stage mycosis fungoides. Arch Dermatol. 1999. 135:1377–1380.

17. Clark C, Dawe RS, Evans AT, Lowe G, Ferguson J. Narrowband TL-01 phototherapy for patch-stage mycosis fungoides. Arch Dermatol. 2000. 136:748–752.

18. Gathers RC, Scherschun L, Malick F, Fivenson DP, Lim HW. Narrowband UVB phototherapy for early-stage mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002. 47:191–197.

19. Ghodsi SZ, Hallaji Z, Balighi K, Safar F, Chams-Davatchi C. Narrow-band UVB in the treatment of early stage mycosis fungoides: report of 16 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005. 30:376–378.

20. Boztepe G, Sahin S, Ayhan M, Erkin G, Kilemen F. Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy to clear and maintain clearance in patients with mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005. 53:242–246.

21. Pavlotsky F, Barzilai A, Kasem R, Shpiro D, Trau H. UVB in the management of early stage mycosis fungoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006. 20:565–572.

22. Gökdemir G, Barutcuoglu B, Sakiz D, Köşlü A. Narrowband UVB phototherapy for early-stage mycosis fungoides: evaluation of clinical and histopathological changes. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006. 20:804–809.

23. Coronel-Pérez IM, Carrizosa-Esquivel AM, Camacho-Martínez F. Narrow band UVB therapy in early stage mycosis fungoides. A study of 23 patients. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2007. 98:259–264.

24. Brazzelli V, Antoninetti M, Palazzini S, Prestinari F, Borroni G. Narrow-band ultraviolet therapy in early-stage mycosis fungoides: study on 20 patients. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2007. 23:229–233.

25. Kural Y, Onsun N, Aygin S, Demirkesen C, Büyükbabani N. Efficacy of narrowband UVB phototherapy in early stage of mycosis fungoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006. 20:104–105.

26. el-Ghorr AA, Norval M. Biological effects of narrow-band (311 nm TL01) UVB irradiation: a review. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1997. 38:99–106.

27. Duthie MS, Kimber I, Norval M. The effects of ultraviolet radiation on the human immune system. Br J Dermatol. 1999. 140:995–1009.

28. Krutmann J, Morita A. Mechanisms of ultraviolet (UV) B and UVA phototherapy. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999. 4:70–72.

29. Dereure O, Picot E, Comte C, Bessis D, Guillot B. Treatment of early stages of mycosis fungoides with narrowband ultraviolet B. A clinical, histological and molecular evaluation of results. Dermatology. 2009. 218:1–6.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download