INTRODUCTION

Acral skin, which is the hairless skin of the palms, soles, and subungal regions, is the most predominant site of malignant melanoma in Asians1. Currently, skin biopsies, such as incisional, excisional, and sometimes multiple punch bioposies, are the diagnostic method of choice for the detection of malignancy. However, depending on the depth of the biopsy and the degree of proliferation of atypical melanocytes, histopathologists and clinicians sometimes have difficulty differentiating pigmented lesions in the plantar or palmar area. Here, we report an unusual case of acral lentiginous melanoma developing from focal melanocytic proliferation. The patient's history included a brownish patch lesion that was present for over 10 years. We suggest that such lesions may be indicative of a very early stage of malignant melanoma. In addition, specific dermoscopy findings including parallel ridge patterns may be very important in diagnosis of early malignant melanotic lesions on acral skin.

CASE REPORT

A 66-year-old female presented with a 1.5×0.8 cm-sized hyperkeratotic plaque on the heel. The lesion showed an irregular border and variegated color, ranging from light brown to black, and was surrounded by a sharply demarcated brownish patch (Fig. 1). The patient said that the lesion had appeared as a small brownish patch approximately 10 years earlier; however, she had noticed a black macular lesion in the center, which had shown progressive growth over a period of 5 years.

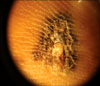

An initial punch biopsy in the junction of the thickest black center of the lesion was conducted at another hospital. Histopathology demonstrated an increase in basal melanocytes and hyperpigmentation with focally uniform cytologic atypia of melanocytes, which was consistent with melanoma in situ (Fig. 2). Dermoscopy (×10, no immersion, Episcope™, Welch Allyn®, Skaneateles Falls, NY) revealed a parallel ridge pattern, abrupt ending of pigmentation, and irregular diffuse pigmentation with focal depigmentation (Fig. 3). Although the results of the initial punch biopsy showed in situ melanoma, we suspected a more invasive malignancy based on clinical and dermoscopic features; therefore, we conducted an excision that included the 5-mm free margin of the lesion. Pathologic evaluation revealed that tumoral melanocytic cell nests with atypical mitosis had been infiltrated by papillary dermis at a Breslow thickness of 2.0 mm (Fig. 4A, 4B). Melanocytes revealed positive staining with HMB-45 and S-100 protein (Fig. 4D, 4E). In addition, we found histological changes in the peripheral brownish patch of the margin of the excision area, which was melanocytic proliferation with focal melanocytic proliferation in the crista profunda intermedia and diffuse basal hyperpigmenation (Fig. 5). We diagnosed this lesion as an acral lentiginous melanoma with peripheral atypical melanosis. General evaluations, including sentinel lymph node biopsy and CT scan, revealed no evidence of regional or systemic metastasis.

The patient was sent to the orthopedic department for wider excision and flap surgery for treatment of the remaining brownish patch lesion with a 5-mm free margin. No evidence of recurrence or metastasis was observed during the 7-month follow-up after tumor excision.

DISCUSSION

In general, acral lentiginous melanoma is considered to be more aggressive and carries a poorer prognosis than other subtypes of melanoma. Findings from recent studies have suggested that the difference in prognosis may be due to delayed diagnosis rather than an actual difference in the biological nature of the tumor2. Metzger et al. reported that misdiagnosis and delayed diagnosis of acral lentiginous melanoma occur more frequently than with other subtypes, and are associated with a poorer outcome3. According to this study, 83 patients with acral melanoma showed a 36% clinical misdiagnosis rate, which caused a median delay of 12 to 18 months. Somach et al. also reported histological comparisons of initial incision biopsy samples with later complete excision of specimens of pigmented lesions, and the presence of invasive melanoma that was not detected by initial sampling was observed in 20% of cases4. This may have been due to the specific anatomical features of the acral area, which is uneven and results in obtaining a biopsy specimen with sufficient width and depth to reflect the whole lesion being difficult.

Another consideration is that histopathological differentiation, as well as clinical differentiation, of melanoma on acral skin is not always easy, especially between early melanoma and melanocytic nevus. Standard criteria for identification of early melanoma include findings of a solitary arrangement of proliferating melanocytes and their migration to the upper epidermis, as well as overall asymmetry in the architecture of the lesion5. In addition, Saida divided melanoma in situ of the sole into three histopathological phases: (I) slightly increased number of melanocytes, some with atypical nuclei, arranged as solitary units in the basal layer of the epidermis; (II) moderately increased number of atypical melanocytes, mostly localized individually in the lower part of the epidermis; and (III) increased number of atypical melanocytes in almost all layers of the epidermis6. Despite these criteria, the degree of melanocytic atypia for diagnosis of early melanoma is sometimes subtle, and leads to interobserver variability.

Several cases of ambiguous melanocytic proliferation on the acral skin have been reported. Among them, atypical melanosis of the foot (AMOF) has interesting features that support this issue. AMOF was first described by Nogita et al. in 19947. The authors defined AMOF as a lesion that is clinically suspicious for acral lentiginous melanoma in situ, but with subtle histopathologic findings and a lengthy duration. Cho et al. also reported a case of acral melanoma developing from a long history of precursor pigmented lesions, which is similar to AMOF8. They suggested that this lesion might be a variant of acral lentigionus melanoma in situ, which is known as acral melanocytic hyperplasia.

However, the relationship between AMOF and acral lentiginous melanoma in situ is still controversial. Kwon et al. reported nine cases of melanocytic proliferation with some atypia on the acral area9. They suggested that these histopathological findings differed from those of AMOF and were regarded as phase I of AML in situ, as described by Saida. Recently, Ishihara et al. suggested that predominant melanocytic proliferation in the crista profunda intermedia observed during histopathology is a critical finding for diagnosis of a very early phase of acral melanoma10. In our case, similar histopathologic features, with focal melanocytic proliferation, predominantly in the crista profunda intermedia, were observed on the peripheral brownish patch lesion surrounding the main melanoma lesion. Because the lesion was a precursor lesion with a history of slow progression to acral lentiginous melanoma over a period of ten years, we suggest that this unusual lesion might be indicative of a very early phase of acral lentiginous melanoma in situ.

Dermoscopy can be a very useful diagnostic tool for differentiation of benign melanocytic lesions from early melanoma that complements the problem of biopsy on acral skin. This non-invasive skin surface microscopy has an advantage of scanning the entire lesion without scarring. Generally, a punch biopsy has been acceptable in the thickest or darkest areas of lesions that are very large or functionally sensitive to total excision. However, because pigmented lesions that are suspicious for malignancy are typically mottled rather than homogeneous, the area chosen for biopsy may not contain the areas that are the most histopathologically advanced. Several studies have reported that the use of dermoscopy increases diagnostic accuracy by up to 30% over clinical visual inspection11. A parallel ridge pattern, showing accentuated pigmentation on the ridges of the skin markings that run mostly in a parallel pattern, is the most critical dermoscopic finding. According to Saida et al., the specificity of this dermoscopic pattern in acral melanoma was 99.0%, and the sensitivity was also high (86.4%) in melanoma of the acral skin12. Yamaura and colleagues have indicated that dermoscopic observations may be superior to histopathologic methods for the detection of early lesions of acral melanoma owing to the specificity of the parallel ridge pattern during detection of acral melanoma in the histopathologically unrecognizable early-development phase13. Recently, in another interesting report by Kilinc Karaarslan et al., dermoscopic features of the parallel ridge pattern were also shown in AMOF14. These findings support the suggestion that dermoscopic findings can be more critical in a histopathologically incredible early phase of malignancy. The nature of ambiguous melanocytic proliferation on acral skin is not yet fully understood. However, dermatologists should always consider the possibility that this subtle lesion can be part of a contiguous phase of invasive tumor growth, and that a more aggressive therapeutic approach is required. To date, many studies of methods for earlier detection of acral melanoma have been conducted, including cyclin D1 gene amplification13 and various image analyses. Among them, we think that dermoscopy is a very useful and reliable tool supporting subtle histopathologic findings; however, more studies and cases are needed to determine the exact nature of these lesions.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download