Abstract

Parry-Romberg syndrome (PRS) is a relatively rare degenerative disorder that is poorly understood. PRS is characterized by slowly progressing atrophy affecting one side of the face, and is frequently associated with localized scleroderma, especially linear scleroderma, which is known as en coup de sabre. This is a report of the author's experiences with PRS accompanying en coup de sabre, and a review of the ongoing considerable debate associated with these two entities. Case 1 was a 37-year-old woman who had right hemifacial atrophy with unilateral en coup de sabre for seven years. Fat grafting to her atrophic lip had been conducted, and steroid injection had been performed on the indurated plaque of the forehead. Case 2 was a 29-year-old woman who had suffered from right hemifacial atrophy and bilateral en coup de sabre for 18 years. Surgical corrections such as scapular osteocutaneous flap and mandible/maxilla distraction showed unsatisfying results.

Parry-Romberg syndrome (PRS), or progressive facial hemiatrophy, was first described by Parry1 in 1825 and Romberg2 in 1846. PRS is a rare disorder of unknown origin, usually developing in the first or second decade of life3,4. This condition is characterized by slowly progressive unilateral facial atrophy of the skin, soft tissue, muscles, and underlying bony structures. PRS commonly affects dermatomes of one or multiple branches of the trigeminal nerve5. Atrophy may be preceded by cutaneous discoloration of the affected skin, such as hyperpigmentation or depigmentation. Hairless patches may also be observed in the affected scalp6.

The incidence and etiology of PRS are still not well known because of its rarity. There is an age-old debate regarding the relationship between PRS and linear scleroderma since they possess similar clinicopathological appearances. Some assert that PRS and linear scleroderma are distinct, but frequently accompanying disorders7, while others include PRS in the same spectrum of linear scleroderma. Plastic surgery using large buried pedicle flaps of dermis and fat, or silicone implants offers some cosmetic benefits. However, the therapeutic modalities are limited and unsatisfactory.

Here, two uncommon cases of PRS accompanying en coup de sabre are described and a discussion of whether these conditions are closely related is provided.

A 37-year-old woman visited our department with a 7-year history of progressive atrophic change on the right side of her face. She first had noticed that areas superior to the right forehead and cheek were hypopigmented seven years ago, at which time she was diagnosed with vitiligo elsewhere. Four years later, atrophy and depression appeared on her nose. After the manifestation of atrophy on the right upper lip and gingiva, a fat graft was conducted. She was referred to our department for persisting brownish atrophic patches on the right cheek and forehead, as well as painful, dry lips. Close examination revealed an ivory-colored hard immovable patch on her forehead, and a soft non-adhesive brownish patch on the same side of the cheek. Moreover, sclerotic recession was observed on her right nasal alae, right upper lip and gingiva (Fig. 1).

There was no family history of similar lesions, nor specific personal trauma or medical history. Laboratory tests, including liver and kidney function tests, showed no remarkable findings, except for antinuclear antibody (ANA) showing a 1:80 positive in a homogenous pattern. Skeletal abnormalities were not found upon X-ray examination of the skull. Physical examination revealed no signs of neurologic abnormalities. The patient refused further radiological studies of the head including computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging.

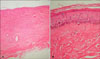

A skin biopsy taken from the right forehead showed an atrophic epidermis and a thickened dermis composed of abundant collagen bundles. There were few inflammatory cell infiltrations in the dermis (Fig. 2). The histologic findings were compatible with scleroderma. Based on the clinical and histological findings, the patient was diagnosed with PRS accompanied by unilateral en coup de sabre.

The patient was treated with topical steroid cream for her right upper lip and intralesional steroid injections for the indurative plaque on her right forehead. It was recommended that she be treated continuously, but she stopped the visits without any improvements.

A 29-year-old woman presented to this hospital department with an 18-year history of gray atrophic patches on her right face. She first had gray atrophic patches on the right side of her chin and neck, and dark brownish sclerotic vertical plaque on both sides of her forehead (Fig. 3). On that occasion, depressions on the cutaneous surface were not distinctive. The lesion had been asymptomatic and not preceded by any trauma. A previously conducted skin biopsy of her forehead confirmed the diagnosis of localized scleroderma. Over the succeeding years, the sclerotic change and atrophy gradually spread to the right side of her nose, periorbital area, forehead, and scalp (Fig. 4A, B). The patient noticed the continuous recession of the lesions. Physical examination of bilateral linear streaks of the forehead revealed a sclerotic tan color extending longitudinally from the frontal scalp to the eyebrow (Fig. 4C, D). Her past treatments included the scapular osteocutaneous flap, mandibular maxilla distraction, and fat graft and injection.

In addition to a lack of trauma, the patient also had no specific previous medical history or related instances in her family history. The results of laboratory studies, including liver and renal function analyses, were within normal limits, and various serologic autoantibodies were negative. Radiographic evaluations using X-rays including panoramic radiography of the teeth and brain CT revealed no abnormal findings.

After diagnosis of PRS with bilateral en coup de sabre based on the clinicopathologic findings, we administered oral penicillamine. However, the patient declined prolonged treatment because of an incessant headache. Therefore, the patient was subsequently treated with intralesional injections of steroid into indurative plaques on both sides of the forehead and scalp, but the lesions persisted. Because the clinical results were unsatisfactory, she was referred to the department of plastic surgery for the further surgical corrections.

PRS is an uncommon degenerative condition characterized by a slowly progressive atrophy that is generally unilateral, and impacts facial tissue, including muscles, bones and skin. The incidence and cause of these alterations are unknown5,8. A cerebral disturbance of fat metabolism has been proposed as a primary cause9,10. Trauma, viral infection, endocrine disturbance, autoimmunity and hereditary are also believed to be associated to the pathogenesis of the disease11-15. However, there was no history of trauma, infection, or underlying autoimmunity in the present cases. The onset of this syndrome often occurs during the first and second decades of life, after which the atrophy slowly progresses over several years, eventually becoming stable11,16-18. However, some patients may have a reactivation of inactive lesions, and the final degree of deformity is usually dependent on the duration of the disease17.

Treatment is still unsatisfactory and limited. Many have attempted to transfer autologous fat tissue to atrophied lesions18. Injection of silicon, bovine collagen and inorganic implants are considered as useful alternatives18,19. However, cosmetic revision is not recommended until the progression of the illness is complete5. Nevertheless, these methods do not completely restore the former appearances because the structures become extinct with time owing to gravity and the absorption of implanted materials. In the current cases, surgical corrections and intralesional steroid injections had been performed, but the patients were not satisfied with the outcome, and we are still searching for new effective modalities.

Many studies have suggested that a close relationship exists between PRS and linear scleroderma, especially en coup de sabre. There have been confused assertions considering the relationship between PRS and en coup de sabre in previous reports because the clinical presentation of en coup de sabre may appear similar to PRS. Moreover, the frequent reports of the coexistence of both diseases may make them much difficult to distinguish. En coup de sabre morphea refers to a lesion of linear morphea that is generally unilateral, and extending longitudinally from the forehead into the frontal scalp20. Paramedian locations are more common than median placements. The involved skin area is depressed, hard, hyperpigmented, and shiny, and may accompany hairless patches.

Many discussions of the relationship between PRS and en coup de sabre eventually condense into two considerations, two distinct disorders, or a continuum. Orozco-Covarrubias et al.7 regarded these two diseases as separate entities because there are differences between PRS and en coup de sabre with respect to their cutaneous and histopathological features. Even though both are rather similar, they thought that the cutaneous sclerosis, hyperpigmentation, and alopecia usually developed in en coup de sabre, while PRS does not show cutaneous sclerosis at any stage. Conversely, Blaszcyk and Jablonska21 described the conversion of en coup de sabre into PRS and suggested that PRS may be a deep variant of en coup de sabre based on the observation of en coup de sabre existing before the development of PRS. Recently, Tollefson and Witman22 also supported the previous belief that both diseases are on the same spectrum. The prevalence of en coup de sabre in conjunction with PRS is uncertain, but has been reported to range from 36.6% to 53.6%22,23. According to Tollefson and Witman22, 15 cases (53.6%) among 28 PRS patients were associated with en coup de sabre. This relatively common coexistence lead them to believe that both disease may share a similar pathogenesis. In addition to these previous studies, the patients described herein displayed both diseases; therefore, we agree with that opinion.

However, even though several cases of PRS accompanied by en coup de sabre have been reported, en coup de sabre with bilateral involvement as in the second case described herein is very rare. In a study conducted Tollefson and Witman22, among 54 patients diagnosed with PRS or en coup de sabre, only one patient had en coup de sabre on one side and PRS on the other. Among the cases of PRS available in the Korean medical literature, only four cases were accompanied by en coup de sabre, and no case showed bilateral involvement24-27.

In conclusion, the clinicopathological similarity of PRS and en coup de sabre and the frequent coexistence of these two diseases in the same patients support our assertion that both diseases are on the same spectrum as the variants of localized scleroderma.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Progessive hemiatrophic change on the right side of face (A), unilateral linear sclerotic brownish patch on the right side of forehead (B), soft non-adhesive brownish patch on the right side of the cheek (C), and sclerotic recession on right nasal alae, right upper lip and gingiva (D). |

| Fig. 2Histological findings of forehead showed slightly atrophic epidermis and thickened dermis composed of abundant collagen bundles (A: H&E, ×40; B: H&E, ×400). |

References

1. Parry CH. Collections from the unpublished medical writings of the late Caleb Hillier Parry. London: Underwoods;1825–478.

2. Romberg HM. Klinische Ergebnisse. 1846. Berlin: Forrtner;75–81.

3. Taylor HM, Robinson R, Cox T. Progressive facial hemiatrophy: MRI appearances. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997. 39:484–486.

4. Goldberg-Stern H, deGrauw T, Passo M, Ball WS Jr. Parry-Romberg syndrome: follow-up imaging during suppressive therapy. Neuroradiology. 1997. 39:873–876.

5. Jurkiewicz MJ, Nahai F. The use of free revascularized grafts in the amelioration of hemifacial atrophy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985. 76:44–55.

6. Jappe U, Hölzle E, Ring J. Parry-Romberg syndrome. Summary and new knowledge based on an unusual case. Hautarzt. 1996. 47:599–603.

7. Orozco-Covarrubias L, Guzmán-Meza A, Ridaura-Sanz C, Carrasco Daza D, Sosa-de-Martinez C, Ruiz-Maldonado R. Scleroderma 'en coup de sabre' and progressive facial hemiatrophy. Is it possible to differentiate them? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002. 16:361–366.

8. Lakhani PK, David TJ. Progressive hemifacial atrophy with scleroderma and ipsilateral limb wasting (Parry Romberg syndrome). J R Soc Med. 1984. 77:138–139.

10. Foster TD. The effects of hemifacial atrophy of dental growth. Br Dent J. 1979. 146:148–150.

11. Mazzeo N, Fisher JG, Mayer MH, Mathieu GP. Progressive hemifacial atrophy (Parry Romberg syndrome). Case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995. 79:30–35.

12. Miller MT, Sloane H, Goldberg MF, Grisolano J, Frenkel M, Mafee MF. Progressive hemifacial atrophy (Parry-Romberg disease). J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1987. 24:27–36.

13. Pensler JM, Murphy GF, Muliken JB. Clinical and ultrastructural studies of Romberg's hemifacial atrophy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990. 85:669–674.

14. Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM. A textbook of oral pathology. 1983. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders;9–10.

16. Moore MH, Wong KS, Proudman TW, David DJ. Progressive hemifacial atrophy (Romberg's disease): skeletal involvement and treatment. Br J Plast Surg. 1993. 46:39–44.

17. Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. Patologia oral & maxilofacial. 1998. 2nd ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan;35.

18. Roddi R, Riggio E, Gilbert PM, Hovius SE, Vaandrager JM, van der Meulen JC. Clinical evaluation of techniques used in the surgical treatment of progressive hemifacial atrophy. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1994. 22:23–32.

19. de la Fuente A, Jimenez A. Latissimus dorsi free flap for restoration of facial contour defects. Ann Plast Surg. 1989. 22:1–8.

21. Blaszczyk M, Jablonska S. Linear scleroderma en Coup de Sabre. Relationship with progressive facial hemiatrophy (PFH). Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999. 455:101–104.

22. Tollefson MM, Witman PM. En coup de sabre morphea and Parry-Romberg syndrome: a retrospective review of 54 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007. 56:257–263.

23. Sommer A, Gambichler T, Bacharach-Buhles M, von Rothenburg T, Altmeyer P, Kreuter A. Clinical and serological characteristics of progressive facial hemiatrophy: a case series of 12 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006. 54:227–233.

24. Kim YJ, Hong YJ, Kim HB. Romberg's syndrome. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1979. 20:567–571.

25. Chang CH, Jung JH, Cho SM, Choi DS. A case of Parry-Romberg syndrome in neonate. J Korean Pediatr Soc. 1999. 42:1589–1593.

26. Kim DH, Shim KW, Choi JU, Kim DS. Parry-Romberg syndrome. Korean J Pediatric Neurosurg. 2006. 3:98–101.

27. Won TH, Park SD, Seo PS. A case of Parry-Romberg syndrome with shortening of ipsilateral lower extremity. Korean J Dermatol. 2008. 46:1216–1220.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download