Abstract

Wolf's isotopic response describes the occurrence of a new, unrelated disease that appears at the same location as a previously healed skin disease, and the most common primary skin disease of this phenomenon is herpes zoster. Several cutaneous lesions have been described to occur at the site of healed herpes zoster, and granulomatous dermatitis and granuloma annulare have been reported to be the most common second diseases. The pathogenesis of the isotopic response is still unclear. Morphea can develop at the site of regressed herpes zoster and a few such cases have been reported. We present here an additional case of morphea that developed at the site of previously healed herpes zoster, and we review the relevant literature.

Several cutaneous lesions have been reported to occur at the site of herpes zoster scar1, and they include comedones, xanthoma, granuloma annulare, granulomatous dermatitis, acneiform eruption, pseudolymphoma, psoriasis, lichen planus, lichen simplex chronicus, eosinophilic dermatosis, cutaneous malignancy, etc2. Wolf et al.3 were the first to use the term isotopic response to describe the appearance of a new skin disease at the site of another, already healed skin disease. The most common primary skin disorder of this phenomenon is herpes virus infection: herpes zoster is most common and herpes simplex and varicella are less frequent2. Morphea can develop at the site of regressed herpes zoster and a few such cases have been reported (Table 1)4-6. We present here an additional case of morphea developing at the site of previously healed herpes zoster and we review the relevant literature.

A 57-year-old Korean man presented with an 8-month history of indurated plaques on the right chest and upper back. One year prior, the patient had developed painful clusters of vesicles in the T2-4 dermatomes on the right side and this had been diagnosed as herpes zoster. He had been treated with oral antiviral drugs and analgesics and the lesions had resolved a month after the onset of the eruption. Three months after the complete resolution of herpes zoster, new indurated patches had developed at the site of the previously healed herpes zoster and the lesions had slowly spread. On the clinical examination, atrophic, hypopigmented, indurated plaques were revealed in the T2-4 dermatomes on the right side, and this all corresponded to the site of the healed herpes zoster (Fig. 1). The plaques were confined to the previous zoster scar. The patient's new lesions had no pruritus and he complained of intermittent, mild postherpetic neuralgia. He reported a history of diabetes mellitus and the laboratory tests were within the normal ranges. The serologic test for Borrelia burgdorferi was negative.

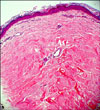

The skin biopsy of the indurated plaque revealed thick and hyalinized bundles of collagen in the dermis and these bundles of collagen were orientated parallel to the skin surface. Perivascular inflammation was sparse and appendages such as pilar apparatus were atrophic and diminished (Fig. 2). The histopathologic findings were consistent with morphea. The patient was diagnosed with morphea at the site of healed herpes zoster as an isotopic response. He was treated with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injection every other week for 3 months and the induration of the skin lesions was prominently improved. But 2 months later, the lesions recurred and spread within the previous herpes zoster scar and the patient was prescribed oral methylprednisolone. Almost complete clearance of the induration and hypopigmentation of the morphea was observed 2 months later, but the lesions relapsed 1 month after the cessation of oral medication. We recommended the patient undergo narrow band UVB treatment, yet he did not want further treatment.

Wolf's isotopic response describes the occurrence of a new, unrelated disease that appears at the same location as a previously healed skin disease3. The interval between the first and the second disease is diverse with a range from days to years3. Several types of cutaneous lesions have been described to occur at the site of healed herpesvirus infection2. The most common second disease appearing at the site is non-specific granulomatous dermatitis and granuloma annulare2.

The underlying pathogenesis leading to the development of the second disease is still unclear1-3. There are several possible hypotheses. It was suggested that viral particles remaining in the tissue are directly responsible for the occurrence of the second disease as a possible mechanism4. The viral DNA isolated in the second disease in the previous studies supports this7,8. Some authors have emphasized that the immunologic and vascular change occurring after viral infection could make the skin more susceptible to a second disease in the same area2,3. Ruocco et al.2 supported the hypothesis that the occurrence of neural alteration could happen first, and the following immunologic dysfunction could be second. The viral and vascular mechanisms could work as cofactors2. The immune system can be influenced by neuropeptides that normal human skin produces (for example, vasoactive intestinal peptide, neuropeptide Y, calcitonin-gene-related peptide, substance P)9. Thus, a disturbed nervous system due to herpesvirus infection may alter the immunologic system and then consequently the skin.

The definitive etiology of morphea is not known, but it has been proposed that trauma10 and previous infection with Borrelia burgdorferi11 can incite morphea. Various studies have shown that the levels of interleukin-13 (IL-13) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) are elevated in the skin of patients with morphea12. TNF plays an important role in leukocyte movement within inflamed tissue by activating chemokines or endothelial cells13. IL-13 modulates monocytes and the B cell function, and it is secreted by activated T cells, mast cells and natural killer cells14,15. TNF and IL-13 are potent stimulators of fibrosis12. In most cases, morphea shows spontaneous regression over 3 to 5 years16. Reactivation of inactive lesion can also occur16. Many therapies have been used to treat morphea. Topical and intralesional corticosteroid can help the lesion to regress due to its anti-inflammatory effect in the early inflammatory stage17. Topical and oral vitamin D analogues18, topical tacrolimus19 and topical imiquimod20 have also been used with successful responses. There are several reports of marked improvement of morphea with using psoralen and ultraviolet A light, broad band ultraviolet irradiation21-23. In our case, intralesional corticosteroid injection prominently reduced the size and induration of the morphea plaques and the administration of oral corticosteroid resulted in the almost clearance of the lesions, yet the patient was not followed up.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Atrophic, hypopigmented, indurated plaques in the T2-4 dermatomes on the right side, corresponding to the site of the previous herpes zoster (black arrow head: biopsy site).

References

1. Requena L, Kutzner H, Escalonilla P, Ortiz S, Schaller J, Rohwedder A. Cutaneous reactions at sites of herpes zoster scars: an expanded spectrum. Br J Dermatol. 1998. 138:161–168.

2. Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Ghersetich I, Bianchi B, Lotti T. Isotopic response after herpesvirus infection: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002. 46:90–94.

4. Zimmermann H. Zoster as a premorbid state of a circumscribed scleroderma. Dermatol Wochenschr. 1964. 150:112–116.

5. Forschner A, Metzler G, Rassner G, Fierlbeck G. Morphea with features of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus at the site of a herpes zoster scar: another case of an isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 2005. 44:524–525.

6. López N, Alcaraz I, Cid-Mañas J, Camacho E, Herrera-Acosta E, Matilla A, et al. Wolf\'s isotopic response: zosteriform morphea appearing at the site of healed herpes zoster in a HIV patient. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009. 23:90–92.

7. Serfling U, Penneys NS, Zhu WY, Sisto M, Leonardi C. Varicella-zoster virus DNA in granulomatous skin lesions following herpes zoster. A study by the polymerase chain reaction. J Cutan Pathol. 1993. 20:28–33.

8. Claudy AL, Chignol MC, Chardonnet Y. Detection of herpes simplex virus DNA in a cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma by in situ hybridization. Arch Dermatol Res. 1989. 281:333–335.

10. Vancheeswaran R, Black CM, David J, Hasson N, Harper J, Atherton D, et al. Childhood-onset scleroderma: is it different from adult-onset disease. Arthritis Rheum. 1996. 39:1041–1049.

11. Aberer E, Neumann R, Stanek G. Is localised scleroderma a Borrelia infection? Lancet. 1985. 2:278.

12. Hasegawa M, Sato S, Nagaoka T, Fujimoto M, Takehara K. Serum levels of tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-13 are elevated in patients with localized scleroderma. Dermatology. 2003. 207:141–147.

13. Sedgwick JD, Riminton DS, Cyster JG, Körner H. Tumor necrosis factor: a master-regulator of leukocyte movement. Immunol Today. 2000. 21:110–113.

14. Zurawski G, de Vries JE. Interleukin 13, an interleukin 4-like cytokine that acts on monocytes and B cells, but not on T cells. Immunol Today. 1994. 15:19–26.

15. Burd PR, Thompson WC, Max EE, Mills FC. Activated mast cells produce interleukin 13. J Exp Med. 1995. 181:1373–1380.

16. Peterson LS, Nelson AM, Su WP. Classification of morphea (localized scleroderma). Mayo Clin Proc. 1995. 70:1068–1076.

17. Joly P, Bamberger N, Crickx B, Belaich S. Treatment of severe forms of localized scleroderma with oral corticosteroids: follow-up study on 17 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1994. 130:663–664.

18. Elst EF, Van Suijlekom-Smit LW, Oranje AP. Treatment of linear scleroderma with oral 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (calcitriol) in seven children. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999. 16:53–58.

19. Mancuso G, Berdondini RM. Localized scleroderma: response to occlusive treatment with tacrolimus ointment. Br J Dermatol. 2005. 152:180–182.

20. Dytoc M, Ting PT, Man J, Sawyer D, Fiorillo L. First case series on the use of imiquimod for morphoea. Br J Dermatol. 2005. 153:815–820.

21. Grundmann-Kollmann M, Ochsendorf F, Zollner TM, Spieth K, Sachsenberg-Studer E, Kaufmann R, et al. PUVA-cream photochemotherapy for the treatment of localized scleroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000. 43:675–678.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download