Abstract

Dowling-Degos disease (DDD) is an autosomal dominant genodermatosis and this disease is a genetically determined disturbance of epidermal proliferation. It is characterized by acquired, slowly progressive pigmented lesions that primarily involve the great skin folds and flexural areas such as the axilla, neck, limb flexures, the inframammary area and the inguinal folds. The vulva is an unusual location for DDD. A 41-year-old woman presented with a 10-year history of multiple, small, reticulated and brownish macules distributed symmetrically on the bilateral external genital regions. We found no other similarly pigmented skin lesions on her body, including the flexural areas. There was no known family history of similar eruptions or pigmentary changes. The histologic examination showed irregular rete ridge elongation with a filiform or antler-like pattern and basilar hyperpigmentation on the tips. Fontana-Masson staining showed increased pigmentation of the rete ridges and the S100 protein staining did not reveal an increased number of melanocytes in the epidermis. From these findings, we diagnosed this lesion as DDD.

Dowling-Degos disease (DDD) is also known as reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures, and this is a rare autosomal dominant genodermatosis that causes abnormal epidermal proliferation1. It is characterized by acquired, slowly progressive pigmented lesions that primarily involve the great skin folds and flexural areas such as the axilla and inguinal folds2. However, there have only been a few previous case reports of DDD on the vulva in the dermatologic literature. We report here on a case of DDD on the vulva of a 41-year-old woman.

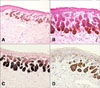

A 41-year-old woman presented with a 10-year history of numerous small, hyperpigmented macules in a reticular pattern on the bilateral external genital regions. We found no other similarly pigmented skin lesions on her body, including the skin folds and flexural areas (Fig. 1). Her medical history was unremarkable and there was no known family history of similar eruptions or pigmentary changes. On the physical examination, there were multiple, small, reticulated and confluent brownish macules distributed symmetrically on the vulva. Histologic examination showed irregular, filiform epidermal elongation of the rete ridges with a concentration of melanin at the tips (Fig. 2A, B). Fontana-Masson staining showed that the hyperpigmentation was mainly limited to the filiform downgrowths (Fig. 2C). The S100 protein staining did not reveal an increased number of melanocytes in the epidermis (Fig. 2D). From these findings, we diagnosed these lesions as DDD.

DDD is an autosomal dominant genodermatosis that is characterized by acquired, slowly progressive pigmented lesions that primarily involve the large body folds and flexural areas such as the axilla, neck, limb flexures, the inframammary area and the inguinal folds1,2. It can occasionally appear on the wrist, face and scalp3. Involvement of the genitalia, and particularly pigmented lesions of the vulva, has been rarely reported1-3. The reported cases are summarized in Table 12,4-6. The disease is more common in women, it presents in adult life and most frequently in the fourth decade7. It usually presents as numerous, small, round pigmented macules that resemble freckles8. The pigmentation is symmetrical and progressive2,8. The degree of pigmentation varies, but in some patients the lesions are almost confluent, giving a brown or black lace-like pattern8. The other features that can be present in DDD are scattered comedo-like lesions and pitted acneiform scars1,8. In our patient, we saw the characteristic features of multiple, small reticulated and brownish macules distributed symmetrically on the bilateral external genital regions.

DDD is believed to be a part of a disease spectrum that includes reticulate acropigmentation of Kitamura (RAK), Haber's syndrome (HS) and reticulate acropigmentation of Dohi (RAD)1,3,7. These may be variants of the same entity with similar clinicopathological features and they overlap in some cases1. The genetic defect of DDD has not yet been well defined9. A recently reported series described the loss of function mutations in the KRT5 gene encoding keratin K5 in two German pedigrees10. KRT5 gene mutations have previously been recognized as being involved in the pathogenesis of epidermolysis bullosa simplex9,10. However, no association between DDD and epidermolysis bullosa simplex has been reported9.

Histopathologically, DDD shows pigmented epidermal rete ridge elongation with a filiform or antler-like pattern and variable basilar hypepigmentation on the tips1. Involvement of the follicular infundibulum, thinning of the suprapapillary epithelium, moderate hyperkeratosis and dermal melanosis have all been observed1,3,6,8. The pigmentation is present as finely dispersed melanin granules scattered uniformly throughout the cytoplasm of the cells6. Fontana-Masson staining reveals that the hyperpigmentation is limited mainly to the epidermal downgrowths. S100 protein staining reveals no increase in the number of melanocytes, and this substantiates that the pigmentation is likely not due to an increased density of melanocytes3,11. The histologic examination for our patient revealed irregular, filiform epidermal elongations of hyperpigmented rete ridges with a concentration of melanin at the tips. No increase in the number of melanocytes was noted on the S100 protein staining.

The differential diagnosis includes lentigo simplex, senile lentigo, adenoid seborrheic keratosis and other hereditary pigmented anomalies2,6. Usually there are only a few scattered lesions in lentigo simplex, without a predilection for areas of sun exposure12,13. They are small, symmetric and well-circumscribed macules that are evenly pigmented, but they vary individually from brown to black13. However, the absence of melanocytic hyperplasia rules out the possibility of a lentigo simplex or other similar melanocytic lesions12,14. The involvement of the infundibulum of the hair follicle is a unique and distinctive feature of the reticular pigmented anomaly: it is not seen in seborrheic keratosis, epidermal nevus or any other lesions12. In addition, hereditary pigmented anomalies such as RAK, HS and RAD need to be differentiated from DDD. A summary of the differences among them is presented in Table 21,3,7,15.

Many treatment options have been tried for DDD, but no treatment has been effective in eliminating the lesion16. Depigmenting agents such as hydroquinone, as well as systemic and topical retinoids, have been used and reported on anecdotally4,11,17. Altomare et al.18 reported a temporary therapeutic benefit after using topical adapalene. Various laser systems, and especially CO2 and Er:YAG lasers, have been proven to be effective11,17. In our case, the patient applied topical agents containing tretinoin, hydroquinone and fluocinolone acetonide (Tri-luma®), but the patient failed to appear for follow-up.

In conclusion, we clinically observed a case of DDD arising on the vulva. This is a rare case in the dermatologic literature, but physicians should consider DDD in the differential diagnosis of pigmented skin diseases.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

(A) Multiple hyperpigmented brownish macules located symmetrically on the bilateral external genital area. (B) A close up view of the reticulate pigmented lesion.

Fig. 2

(A) The epidermal downgrowths showed a filiform or antler-like pattern with irregular elongation of the rete ridges in the lesion (H&E, ×100). (B) There is increased melanin pigment at the tips of the epidermis (H&E, ×200). (C) There is increased pigmentation of the rete ridges on Fontana-Masson staining (Fontana-Masson, ×200). (D) Compared with perilesional normal skin, the S100 protein staining reveals no increase in the number of melanocytes (S100 protein, ×200).

References

1. Rubio C, Mayor M, Martín MA, González-Beato MJ, Contreras F, Casado M. Atypical presentation of Dowling-Degos disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006. 20:1162–1164.

2. Massone C, Hofmann-Wellenhof R. Dermoscopy of Dowling-Degos disease of the vulva. Arch Dermatol. 2008. 144:417–418.

3. Kim YC, Davis MD, Schanbacher CF, Su WP. Dowling-Degos disease (reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures): a clinical and histopathologic study of 6 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999. 40:462–467.

4. Jones EW, Grice K. Reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures. Dowing Degos disease, a new genodermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1978. 114:1150–1157.

5. Milde P, Goerz G, Plewig G. Dowling-Degos disease with exclusively genital manifestations. Hautarzt. 1992. 43:369–372.

6. O'Goshi K, Terui T, Tagami H. Dowling-Degos disease affecting the vulva. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001. 81:148.

7. Wenzel G, Petrow W, Tappe K, Gerdsen R, Uerlich WP, Bieber T. Treatment of Dowling-Degos disease with Er:YAG-laser: results after 2.5 years. Dermatol Surg. 2003. 29:1161–1162.

8. Harper JI, Trembath RC. Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Genetics and genodermatoses. Rook's textbook of dermatology. 2004. 7th ed. Malden: Blackwell;12.82.

10. Betz RC, Planko L, Eigelshoven S, Hanneken S, Pasternack SM, Bussow H, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the keratin 5 gene lead to Dowling-Degos disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2006. 78:510–519.

11. Jeon HJ, Kim SH, Whang KK, Hahm JH. A case of reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures (Dowling-Degos disease). Korean J Dermatol. 2006. 44:877–880.

12. Howell JB, Freeman RG. Reticular pigmented anomaly of the flexures. Arch Dermatol. 1978. 114:400–403.

13. Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Murphy GF, Xu X. Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL, Murphy GF, Xu X, editors. Benign pigmented lesions and malignant melanoma. Lever's histopathology of the skin. 2008. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven;708–709.

14. Juhn BJ, Lee MH, Haw CR. A case of Dowling-Degos disease. Korean J Dermatol. 1999. 37:752–755.

15. Alfadley A, Al Ajlan A, Hainau B, Pedersen KT, Al Hoqail I. Reticulate acropigmentation of Dohi: a case report of autosomal recessive inheritance. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000. 43:113–117.

16. Fenske NA, Groover CE, Lober CW, Espinoza CG. Dowling-Degos disease, hidradenitis suppurativa, and multiple keratoacanthomas. A disorder that may be caused by a single underlying defect in pilosebaceous epithelial proliferation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991. 24:888–892.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download