Abstract

Ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) is a well-recognized cutaneous infection that most commonly affects immunocompromised patients. It typically occurs on the extremities, or in gluteal and perineal regions. Although Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the most well-known pathogen causing EG, other organisms have been reported to cause EG. Herein we report a rare case of ecthyma gangrenosum presenting as aggressive necrotic skin lesions in perioral and infraorbital areas in a 47-year-old patient with acute myelocytic leukemia after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. It was caused by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, which is an aerobic, gram-negative pathogen that has been associated only rarely with cutaneous disease. Blood culture and tissue culture were positive for S. maltophilia. Histological examination revealed numerous tiny bacilli in the dermis and perivascular area. Early recognition of skin lesions caused by S. maltophilia is important to decrease associated mortality in immunosuppressed patients.

Ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) is a well known cutaneous manifestation that most commonly affects immunosuppressed and burn patients1,2. It usually occurs as a result of bacteremia or, rarely, as a primary cutaneous lesion. The lesions are present in the gluteal and perineal regions or on the extremities, but they can occur anywhere on the body1,3,4. Most cases of ecthyma gangrenosum are associated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia5,6. But numerous other organisms have been reported to cause EG.

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia is an aerobic gram-negative bacillus that is a frequent colonizer of fluids used in hospital settings. The incidence of S. maltophilia infection has been increasing. Until now, one case of S. maltophilia infection, paronychia, have been reported in Korea7, and several cases of mucocutaneous, skin and soft tissue infection have been reported abroad8-10.

It is important to identify early the skin lesions caused by S. maltophilia because it is associated with a high mortality in immunocompromised hosts.

A 47-year-old man with a history of AML stage M2 was admitted to the hematology-oncology department due to high fever. Nine days after an allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, he developed a 38.8℃-high fever. Intravenous cefazolin, teicoplanin, metronidazole, and meropenem were maintained after admission. The next day, he developed rapid, progressive, severe, edematous, erythematous, and necrotic plaques with bullae formation around the lips (Fig. 1) and was referred to the dermatology department for evaluation of the skin lesions. A skin biopsy from a perioral necrotic hemorrhagic vesicle with blood culture, fungus culture, and open pus culture was performed. Two days later, he suffered from bradycardia, hypotension, and respiratory distress and expired. Blood and tissue culture results revealed S. maltophilia which was resistant to the antibiotics that he had been treated with; this pathogen was sensitive to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Although an autopsy was not done, the cause of death was probably sepsis caused by S. maltophilia.

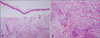

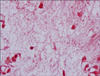

The histopathologic findings included a sub-epidermal blister with hemorrhage and dermal edema with vascular congestion (Fig. 2A). There was perivascular cuffing with basophilic deposits accompanied by a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes in the dermis. Basophilic deposits suggestive of bacterial colonies surrounded the affected vessels and were scattered in the interstitial dermis. In addition, intravascular thrombosis was present with endothelial swelling (Fig. 2B). A tissue Gram stain revealed basophilic deposits to be collections of gram-negative bacilli which were subsequently identified as S. maltophilia on blood culture (Fig. 3).

EG is a rare necrotizing vasculitis3 and a well recognized manifestation that occurs in debilitated persons who are suffering from leukemia, in severely burned patients, in pancytopenia or neutropenia, and in patients with a functional neutrophilic defect, terminal carcinoma, or other severe chronic diseases1. It most commonly affects immunocompromised and burn patients but it also occurs in the perineal area of healthy infants after antibiotic therapy in conjunction with maceration of the diaper area1,3. The skin lesions of ecthyma gangrenosum are the manifestation of a necrotizing vasculitis3. The lesion characteristically begins as an erythematous nodule, macule, vesicle, or bullae and evolves into gangrenous ulcerations with black eschar and a surrounding rim of erythema6,11,12. The vesicles, initially filled with serous fluid, appear on the surface of the edematous skin, and then coalesce to form large bullae. The bullae slough away, leaving ulcerated, necrotic centers with erythematous halos3,13. The maturation of the lesion is very rapid and often occurs in less than 24 hours as in our patient11. Fifty seven percent of skin lesions were located in the gluteal region, 30% on the extremities including the axillae, and 6% on the trunk. Facial involvement is unusual, occurring only in 6% of cases3.

The pathogenic mechanism of EG is unknown, but several possible mechanisms have been suggested6. Two mechanism of EG have been well described. In classic bacteremic EG, the skin lesions are considered to represent blood-borne metastatic seeding of an organism into the skin5,6,14. Our patient also revealed a positive blood culture result. In nonbacteremic EG, the lesion is located at the site of entry or inoculation of the organism into the skin5,6. Some investigators have suggested that non-bacteremic EG may be an early type of EG6.

Although Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the most common pathogen of EG-associated bacteremia, other organisms have been reported. The most commonly reported one are Citrobacter freundii, Aeromonas hydrophila, and Escherichia coli3,5,15. Our case is unique in that the patient's EG lesion was caused by a rarely isolated gram-negative bacillus, S. maltophilia.

Histopathologically, EG is characterized by epidermal necrosis with hemorrhage and dermal infarction, usually accompanied by a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate of lymphocytes, hisitocytes and neutrophils1,2. In general, acute mixed inflammatory cell infiltration and vascular proliferation are seen in the dermis, often involving the subcutaneous tissue6. Gram negative bacilli may be seen in the dermis and involving the media and adventitia of venules, but not the intima. Vasculitis and thrombosis may be present2. Since numerous Gram-negative basophilic bacilli were observed, mainly in the dermis and perivascular area in our case, skin lesions are speculated to be secondary to bacteremia.

Early diagnosis and effective therapy are essential in the management of EG6. Treatment of EG involves the use of appropriate systemic antibiotics according to biopsy and blood culture results11. A combination of an aminoglycoside and an anti-pseudomonal β-lactam antibiotics is recommended for treatment of both bacteremic and non-bacteremic EG6,11. Nonbacteremic patients with EG have relatively low mortality, ranging from 7% to 15% in a recent series, but the mortality rate in patients with bacteremia ranges from 38% to 96%3. The physical finding of bullous cellulitis is associated with higher mortality, and the number of skin lesions is positively correlated with the severity of the disease3. Other prognostic factors include the time of onset of antibiotic therapy and the patient's response to therapy11.

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, formerly named Xanthomonas maltophilia and Pseudomonas maltophilia, is an aerobic, gram-negative bacillus and has emerged as an important opportunistic nosocomial infection often associated with central venous catheter-related bacteremia16,17. It is a frequent colonizer of fluids used in the hospital setting, such as nebulizers, dialysis machines, water baths and intravenous fluids8. Colonization with S. maltophilia is seen to a greater degree in patients treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics as in our patient10. It grows slowly in disinfectant agents and has a high rate of mutation, which can confer resistance to antibiotics16. Resistance to beta-lactams, carbapenems, aminoglycosides, and quinolones is well known16.

Skin and soft tissue manifestations of S. maltophilia infection are becoming increasingly well recognized8,9, and are most frequently associated with posttraumatic, post-surgical, or burn-related wounds and chronic cutaneous ulcers16. Clinical manifestations include cellulitis, cellulitis-like skin lesions, infected mucocutaneous ulcers, EG and paronychia7-10,18. The route of transmission is mainly unknown but it seems likely that invasion takes place via defects in mucous membranes and by colonization of central venous catheters10.

Infections with S. maltophilia can be life-threatening because of its pathogenicity, intrinsic resistance to many antibiotics and the general condition of patients affected16. Jang et al.18 found that among their 32 cases who did not receive appropriate antimicrobial therapy, none survived. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) is recommended as the agent of choice for therapy of S. maltophilia infection as it is found to be active against most strains although resistance is increasing. Ticarcillin-clavulanate is noted to have good activity and is suggested as the agent of choice in individuals intolerant of TMP-SMX8,14,19.

The recovery from S. maltophilia infection is dependent on treatment with appropriate antibiotics, reversal of myelosuppression and removal of intravenous catheters8,14. Hematologic malignancy, transplantation, neutropenia, immunosuppressive therapy and a high severity of illness score (based on temperature, presence of hypotension, mental status and need for ventilatory support) were important prognostic factors8,20. Early diagnosis and appropriate antibiotic therapy are also critical for improving the prognosis of S. maltophilia infection8,18.

S. maltophilia skin infection should be included in the list of differential diagnoses for skin lesions in neutropenic patients, especially the ones with an underlying hematologic malignancy, who have received recent chemotherapy and broad spectrum antibiotics.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 2(A) Skin biopsy specimen showing subepidermal blister with hemorrhage and dermal edema with vascular congestion (H&E, ×100). (B) Perivascular cuffing with basophilic deposits accompanied by a mixed inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes in dermis. Intravascular thrombosis was present with endothelial swelling (H&E, ×200). |

References

1. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews' diseases of the skin: clinical dermatology. 2006. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier;271–272.

2. McKee PH, Calonje E, Granter SR. Pathology of the skin: with clinical correlations. 2005. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby;869–871.

3. Downey DM, O'Bryan MC, Burdette SD, Michael JR, Saxe JM. Ecthyma gangrenosum in a patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Burn Care Res. 2007. 28:198–202.

4. Pandit AM, Siddaramappa B, Choudhary SV, Manjunathswamy BS. Ecthyma gangrenosum in a new born child. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003. 69:52–53.

5. Reich HL, Williams Fadeyi D, Naik NS, Honig PJ, Yan AC. Nonpseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004. 50:5 Suppl. S114–S117.

6. Song WK, Kim YC, Park HJ, Cinn YW. Ecthyma gangrenosum without bacteraemia in a leukaemic patient. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001. 26:395–397.

7. Lee GY, Choi YW, Choi HY, Myung KB. A case of onychia and paronychia by Sternotrophomonas maltophilia. Korean J Dermatol. 2001. 39:89–90.

8. Teo WY, Chan MY, Lam CM, Chong CY. Skin manifestation of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infection--a case report and review article. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2006. 35:897–900.

9. Sakhnini E, Weissmann A, Oren I. Fulminant Stenotrophomonas maltophilia soft tissue infection in immunocompromised patients: an outbreak transmitted via tap water. Am J Med Sci. 2002. 323:269–272.

10. Moser C, Jonsson V, Thomsen K, Albrectsen J, Hansen MM, Prag J. Subcutaneous lesions and bacteraemia due to Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in three leukaemic patients with neutropenia. Br J Dermatol. 1997. 136:949–952.

11. Solowski NL, Yao FB, Agarwal A, Nagorsky M. Ecthyma gangrenosum: a rare cutaneous manifestation of a potentially fatal disease. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004. 113:462–464.

12. Zomorrodi A, Wald ER. Ecthyma gangrenosum: considerations in a previously healthy child. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002. 21:1161–1164.

13. Singh TN, Devi KM, Devi KS. Ecthyma gangrenosum: a rare cutaneous manifestation caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa without bacteraemia in a leukaemic patient--a case report. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2005. 23:262–263.

14. Boisseau AM, Sarlangue J, Perel Y, Hehunstre JP, Taieb A, Maleville J. Perineal ecthyma gangrenosum in infancy and early childhood: septicemic and nonsepticemic forms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992. 27:415–418.

15. Rodot S, Lacour JP, van Elslande L, Castanet J, Desruelles F, Ortonne JP. Ecthyma gangrenosum caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int J Dermatol. 1995. 34:216–217.

16. Smeets JG, Lowe SH, Veraart JC. Cutaneous infections with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in patients using immunosuppressive medication. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007. 21:1298–1300.

17. Dignani MC, Grazziutti M, Anaissie E. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infections. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2003. 24:89–98.

18. Jang TN, Wang FD, Wang LS, Liu CY, Liu IM. Xanthomonas maltophilia bacteremia: an analysis of 32 cases. J Formos Med Assoc. 1992. 91:1170–1176.

19. Betriu C, Sanchez A, Palau ML, Gomez M, Picazo JJ. Antibiotic resistance surveillance of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, 1993-1999. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001. 48:152–154.

20. del Toro MD, Rodriguez-Bano J, Herrero M, Rivero A, Garcia-Ordonez MA, Corzo J, et al. Clinical epidemiology of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia colonization and infection: a multicenter study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2002. 81:228–239.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download