Abstract

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is related diseases characterized by proliferation of Langerhans cell with involvement of bone, skin, lung and other organs. LCH usually occurs in childhood and are presented as multiple small papules or eczematoid lesion mostly. We report a 50-year-old man with 3 brown lichenoid patches on left dorsal foot. He was diagnosed pulmonary LCH 5 years ago. Typical LC cells on skin lesion and CD1 complex positive staining confirm the diagnosis of LCH. We consider brown lichenoid patches may be a previously unreported cutaneous presentation in cutaneous or multisystem LCH.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare, clinically polymorphous group of disorders all having in common proliferation of Langerhans cells. The recognized clinical variants of LCH include Letterer-Siwe disease, Hand-Schuller-Christian disease, eosinophilic granuloma, and congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis1. We report a 50-year-old man with brown lichenoid patches, unusual cutaneous presentation of LCH, on left dorsal foot.

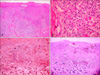

A 50-year-old man attended Department of Dermatology with a 2 year duration of brown-colored patches on the left dorsal foot. Lobular consolidation was shown on chest X-ray in health screening 5 years ago, but he had no symptoms. He was diagnosed pulmonary LCH by chest CT and percutaneous transthoracic needle aspiration. He is a heavy smoker and has 45 pack-years smoking history. On physical examination, there were three brown lichenoid patches on left dorsal foot (Fig. 1). Any regional lymph node is not palpable. His laboratory findings were all within normal range. Initial chest CT showed lobular consolidation at left basal segment of left lower lobe (Fig. 2). Regular enhanced chest CT in every 3 months revealed no interval change in pulmonary LCH lesion. A biopsy specimen of cutaneous lesion showed dense infiltrations in the dermis and dermoepidermal junction. The infiltrations consist of numerous histiocytes and few lymphocytes. Histiocytes appear as large, round cells with abundant cytoplasm and indented eccentric nucleus (Fig. 3A, B). Immunochemistry for CD 1a complex and S-100 protein showed positive staining but CD 68 show negative (Fig. 3C, D). The patient did not receive treatment but he visited our Department of Pulmonary Medicine regularly. To his last visit (1 year later) we can't find any changes on pulmonary and cutaneous lesions.

LCH encompasses a group of disorders of unknown origin with widely diverse clinical presentations and outcomes, characterized by infiltration of the involved tissues by large numbers of LC. LCH is characterized clinically by various combinations of systemic and cutaneous manifestations. LCH consists of Letterer-Siwe disease, Hand-Schuller-Christian disease, eosinophilic granuloma, and congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis1.

The definite diagnosis of LCH should fit light microscopy histology and at least 1 of the 2 following factors: 1) Birbeck's granules by electron microscopy, 2) labeling of CD1 antigen on pathological cells2. On light microscopy, the typical LCH cells are approximately four to five times larger than lymphocytes and have a vesiculated, reniform (kidney-shaped) nucleus and abundant, slightly eosinophilic cytoplasm. Sometimes, indeterminate cell histiocytosis (ICH) closely resembles LCH clinically and histologically. The cells in ICH are positive for S-100 protein, but show variable reactivity for CD1a. Macrophage markers, such as KP1 (CD68) and Ki-M1p, are often positive. No Birbeck granules are seen ultrastructurally3. In this case, we confirmed LCH by his past history, many LC infiltration in H&E stain and immunochemical positivity for S-100 protein and CD1a and negativity for macrophage markers.

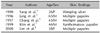

Five cases of adult cutaneous LCH were noted in Korean Dermatologic literature (Table 1)4-8. Although LCH is commonly thought to be confined to children, a small percentage of patients are elderly and may have cutaneous involvement for many years before the onset of visceral disease9. Adult LCH has difference with childhood LCH in organ involvement. Bone disease is most common in childhood LCH, but pulmonary disease is very frequent in adult LCH. Skin disease and diabetes insipidus are frequent in both type10.

Cutaneous manifestations are common in multi-organ involved LCH and adult LCH skin lesions are similar that of childhood. The typical lesion is yellowish or reddish small multiple papules with ulceration, crusting or a hemorrhagic change on the trunk and scalp. Especially the scalp lesions resemble seborrheic dermatitis and other common finding is an eczematous lesion on intertriginous area11.

On the other hand, unusual cutaneous manifestations of LCH such as varicelliform eruption, solitary nodule and nail fold swelling are also reported (Table 2)12-19. In this case, cutaneous lesions are shown as brown lichenoid patches on left dorsal foot and we consider this is rare in LCH patients.

Surgery, steroid cream, topical nitrogen mustard, interferon IL, PUVA, isotretinoin, thalidomide can be treatment for skin manifestations of LCH. Single system-patients should receive prednisone and vinblastine for 6 wk followed by continuation treatment with 6-mercaptopurine, prednisone, and vinblastine for 6 months. Patients with multisystem disease should receive prednisone and vinblastine for 6 wk followed by continuation treatment with 6-mercaptopurine, prednisone, and vinblastine for 6 or 12 months, respectively20.

LCH presents a very wide clinical spectrum and variable course. Prognostic factors are including age of patients at diagnosis, numbers of organ involved and organ dysfunction. Single system disease is usually associated with a good prognosis, but multisystem disease may be fatal11.

Figures and Tables

References

2. Writing Group of the Histiocyte Society. Histiocytosis syndromes in children. Lancet. 1987. 1:208–209.

3. Ratzinger G, Burgdorf WH, Metze D, Zelger BG, Zelger B. Indeterminate cell histiocytosis: fact or fiction? J Cutan Pathol. 2005. 32:552–560.

4. Sang YH, Choi IC, Jun JB, Kim DW, Chung SL. Histiocytosis-X with chronic weeping ulcers in the anogenital areas. Ann Dermatol. 1990. 2:128–131.

5. Jung WK, Kim YK, Whang KW, Lee HK, Park HS, Won JH. A case of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult. Ann Dermatol. 1996. 8:25–29.

6. Chang SE, Choi JH, Sung KJ, Moon KC, Koh JK. A case of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adult treated with 5-chlorodeoxyadenosine. Korean J Dermatol. 1997. 35:Suppl 2. 118.

7. Kim SH, Jang SE, Choi JH, Sung KJ. A case of histiocytosis X in an adult treated with Interferon alpha 2b. Korean J Dermatol. 1999. 37:Suppl 2. 77.

8. Lee SJ, Ban EH, Park JH, Choi KS, Lee JH, Kim YG, et al. A case of Letterer-Siwe disease in adult. Korean J Dermatol. 2000. 38:Suppl 1. 137.

9. Winkelmann R. Adult histiocytic skin diseases. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 1981. 115:67–76.

10. Arico M. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults: more questions than answers? Eur J Cancer. 2004. 40:1467–1473.

11. Caputo R. Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, editors. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. 2003. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill;1581–1589.

12. Modi D, Schulz EJ. Skin ulceration as sole manifestation of Langerhans-cell histiocytosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1991. 16:212–215.

13. Johno M, Oishi M, Kohmaru M, Yoshimura K, Ono T. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as a varicelliform eruption over the entire skin. J Dermatol. 1994. 21:197–204.

14. Mejia R, Dano JA, Roberts R, Wiley E, Cockerell CJ, Cruz PD Jr. Langerhans' cell histiocytosis in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997. 37:314–317.

15. Aoki M, Aoki R, Akimoto M, Hara K. Primary cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult. Am J Dermatopathol. 1998. 20:281–284.

16. Jain S, Sehgal VN, Bajaj P. Nail changes in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000. 14:212–215.

17. Lee JR, Choi GS, Koo SW, Lee SC, Kim YK. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as a solitary nodule. Korean J Dermatol. 2001. 39:459–462.

18. Holme SA, Mills CM. Adult primary cutaneous Langerhans' cell histiocytosis mimicking nodular prurigo. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002. 27:250–251.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download