Abstract

Background

Progressive macular hypomelanosis is characterized by ill-defined, non-scaly, hypopigmented macules primarily on the trunk of the body. Although numerous cases of progressive macular hypomelanosis have been reported, there have been no clinicopathologic studies of progressive macular hypomelanosis in Korean patients.

Objective

In this study we examined the clinical characteristics, histologic findings, and treatment methods for progressive macular hypomelanosis in a Korean population.

Methods

Between 1996 and 2005, 20 patients presented to the Department of Dermatology at Busan Paik Hospital with acquired, non-scaly, confluent, hypopigmented macules on the trunk, and with no history of inflammation or infection. The medical records, clinical photographs, and pathologic findings for each patient were examined.

Results

The patients included 5 men and 15 women. The mean age of onset was 21.05±3.47 years. The back was the most common site of involvement. All KOH examinations were negative. A Wood's lamp examination showed hypopigmented lesions compared with the adjacent normal skin. A microscopic examination showed a reduction in the number of melanin granules in the lesions compared with the adjacent normal skin, although S-100 immunohistochemical staining did not reveal significant differences in the number of melanocytes. Among the 20 patients, 7 received topical drug therapy, 6 were treated with narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy, 4 received oral minocycline, and 3 did not receive any treatment.

Conclusion

Most of the patients with progressive macular hypomelanosis had asymptomatic ill-defined, non-scaly, and symmetric hypopigmented macules, especially on the back and abdomen. Histologically, the number of melanocytes did not differ significantly between the hypopigmented macules and the normal perilesional skin. No effective treatment is known for progressive macular hypomelanosis; however, narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy may be a useful treatment modality.

Progressive macular hypomelanosis (PMH) of the trunk was first described in 1988 by Guillet et al.1. Previous reports have referred to this condition as cutis trunci variata2, dyschromia creole3, or idiopathic multiple large macule hypomelanosis4. PMH is characterized by non-scaly, hypopigmented macules on the trunk and upper extremities, with no history of skin disease. The histologic findings include decreased numbers of epidermal melanin granules in hypopigmented lesions compared with normal skin1. Current treatments for PMH include topical and systemic antifungal agents, topical steroids, and psoralen with ultraviolet A light (PUVA). However, no consistently effective therapy is known. Cases of PMH in Koreans have been reported in the literature5,6, but no clinicopathologic studies of PMH in Korean patients have been published. The purpose of the current study was to document the clinical, pathologic, and histologic properties and treatment methods for 20 Korean patients who were diagnosed with PMH over a 10-year period.

Patients with acquired, non-scaly, confluent, hypopigmented macules and with no history of skin disease who were treated in the Department of Dermatology at Busan Paik Hospital between June 1996 and May 2005 were enrolled in the study. Other infectious hypopigmented macular diseases (tinea versicolor and leprosy), inflammatory diseases (hypopigmented mycosis fungoides, pityriasis alba, psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, and pityriasis rubra pilaris), and other disorders of pigmentation (albinism, depigmented nevus, vitiligo, and idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis) were excluded by KOH mounts, Wood's lamp examinations, or skin biopsies.

We collected information on gender, age at the time of the hospital evaluation, duration of the disease, distribution of hypopigmented lesions, skin manifestations, subjective symptoms, family history, associated disorders, treatment methods, and treatment response by reviewing the medical records and clinical photographs for each patient. We also conducted telephone interviews to verify the clinical responses. The distribution of the lesions was recorded separately according to location.

Skin biopsies were obtained from all patients. In 5 of the 20 patients, a single pair of 4-mm punch biopsies was obtained from comparable anatomic sites on the hypopigmented lesions and normal skin. The other 15 patients underwent skin biopsy at the boundary between the lesion and normal skin. We examined the samples for epidermal melanin pigmentation and dermal perivascular or perifollicular inflammatory infiltration. The specimens from 5 patients were processed for S-100 immunohistochemistry, and the number of epidermal melanocytes was compared between the specimens. We then counted and averaged the numbers of S-100-positive melanocytes from the hypopigmented lesions and normal skin samples by examining 3 visual fields at a magnification of ×400.

Seven patients were instructed to apply topical drugs; 4 patients received 1% hydrocortisone lotion, 0.05% desonide lotion, or prednicarbate ointment; 2 patients were treated with 0.025% tretinoin cream; and 1 patient was treated with 1% pimecrolimus cream once or twice daily. Six patients were treated with narrow-band ultraviolet B (NBUVB) phototherapy once or twice a week. The initial light dose was 400 mJ/cm2; if no side effects were observed, the dose was subsequently increased by 10~20%. If the patient complained of erythema or pruritus, the light dose was kept the same. If pain or a burning sensation was reported, the light dose was decreased by 20%. Four patients received oral minocycline at 100~200 mg/day. The clinical repigmentation rate was assessed by a dermatologist on a 5-point scale as follows: 0, no repigmentation; 1, 1~29% repigmentation; 2, 30~59% repigmentation; 3, 60~89% repigmentation; and 4, ≥ 90% repigmentation.

The results are presented as the mean±standard deviation and were calculated using SAS 9.12 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The melanocyte counts were compared between the hypopigmented lesions and normal skin samples using a t-test and Wilcoxon's rank-sum test, respectively. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

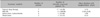

Of the 20 patients, 5 were males and 15 were females. The patients ranged in age from 14~28 years, with a mean of 23.85±3.50 years. The age of onset ranged from 13~27 years, with a mean of 21.05±3.47 years. Five adolescents and 15 patients in their 20s were diagnosed with PMH. The distribution of the lesions was variable. Most of the lesions were detected on the back (18 cases) or abdomen (17 cases), although some patients displayed lesions on their buttocks (6 cases) or upper chest (1 case). Two patients complained of pruritus, but the majority of the patients were asymptomatic. The interval of time between the patient's awareness of pigment change to the hospital evaluation was <5 years for 17 patients and 6~10 years for 3 patients (overall average, 2.79±2.67 years). All of the lesions were symmetrically localized and illdefined. All of the patients exhibited nummular and non-scaly, round-to-oval, confluent, hypopigmented macules (Fig. 1, 2A). The KOH mounts of skin scrapings were negative in all cases. The Wood's lamp examinations revealed some contrast between the hypopigmented lesions and the adjacent normal skin. One patient had a left posterior cerebral artery infarction; however, none of the other patients had any accompanying family history (Table 1).

Staining with hematoxylin and eosin showed that the deposition of melanin in the hypopigmented lesions was significantly lower than in the adjacent normal skin. There was no sign of perivascular or perifollicular inflammatory infiltration (Fig. 3). The number of S-100-positive melanocytes did not differ significantly between the hypopigmented macules and the normal perilesional skin, as observed in 3 visual fields at a magnification of ×400 (p>0.05; Table 2, Fig. 4).

Of the 20 patients, 7 received topical drug therapy, 6 were treated with NBUVB phototherapy, 4 received oral minocycline, and 3 did not receive any treatment. All 6 patients who received NBUVB therapy presented with repigmentation (Fig. 2B). After 3~13 months, no depigmentation recurred. NBUVB treatment was administered a mean of 12.33±3.56 times at a mean light dose of 10.75±3.06 J/cm2.

Of the four patients who received oral minocycline, only one had a clinically favorable response; the mean duration until repigmentation was 1 year. In the topical drug therapy group, 4 patients received corticosteroids, 2 were treated with tretinoin, and 1 was treated with pimecrolimus. In the topical drug therapy group, only 1 patient who had used 1% hydrocortisone lotion was clinically cleared; the time-to-repigmentation was 3.33 years. One of the patients who received no treatment showed clinical improvement, with a time-to-repigmentation of 8.33 years (Table 3).

Guillet et al.1 reported hypopigmented macules on the trunk in patients of mixed ethnic origin (black/white) in 19851. Guillet et al.1 later coined the term PMH of the trunk in 1988. PMH is an idiopathic skin disorder characterized by hypopigmented macules predominantly located on the trunk without scales or a history of skin problems. PMH is more common in tropical and subtropical regions than in other geographic areas. In Korea, there have been only three published case reports of PMH, and there have been no studies pertaining to the prevalence of PMH5,6. In the present study, we excluded all patients who declined a skin biopsy, even if they showed typical symptoms of PMH. Although we do not know the exact prevalence of PMH, it is likely that PMH is not a rare disease in Korea. Moreover, PMH may be more common in young women. The proportion of males-tofemales in this study was 1:3, and the mean age of onset was 21.05±3.47 years, which is compatible with the predominance of PMH in young female patients. However, women are known to access the healthcare system more than men, especially their cosmetic problems, therefore, the frequency measurements in men and women may have some limitations.

Clinically, PMH is characterized by ill-defined, non-scaly, round-to-oval, asymptomatic, and symmetric hypopigmented macules. Indeed, the lesions may become confluent, forming large hypopigmented macules after an increase in their number1. The patients in our study presented with the clinical characteristics described by Guillet et al.1. The histopathologic findings in PMH are usually non-specific, but one common feature is that the melanin content in the lesions is lower than that in normal skin7. The ultrastructural findings in PMH include decreased epidermal levels of melanin and fewer melanized melanosomes in the lesional skin8. Choi and Hann5 reported a mild perivascular inflammatory cell infiltration and dermal melanophages, and Westerhof et al.9 reported gram-positive bacteria in pilosebaceous units. The number of melanin granules in the skin lesions of our patients appeared to be lower than in the adjacent normal skin, but no other findings were observed (Fig. 3).

Immunohistochemical staining with anti-S-100 antibodies revealed no significant difference in the number of melanocytes between the hypopigmented lesions and normal skin (Table 2, Fig. 4).

The etiology of this condition is uncertain, but many hypotheses have been proposed. Guillet et al.1 suggested that ethnicity is an important factor, and Borelli2 classified PMH as a genetic dermatosis. However, none of the 20 patients we examined had a family history of PMH, and we could not find any genetic influence. Sober and Fitzpatrick4 proposed a relationship with tinea versicolor, but that was excluded in our study. Moreover, there was no development of Malassezia furfur in the PMH lesions. Using a Wood's lamp, Westerhof et al.9 observed a follicular pattern of red fluorescence inside the lesional skin of patients with PMH, and Propionibacterium acnes was isolated from biopsies of lesional follicular skin in all patients except one. It was concluded that P. acnes, which is detected in pilosebaceous units, produces a factor that interferes with melanogenesis. Thus, P. acnes is a suggested etiologic factor in PMH. Many of the patients in our study were enrolled before 2004, when P. acnes was proposed as a cause of PMH; therefore, a Wood's lamp examination for the observation of a follicular pattern of red fluorescence was not performed. Hypopigmented lesions usually develop at sites that are not exposed to sunlight, and NBUVB phototherapy improves the skin lesions in patients with PMH. Therefore, we propose that epidermal melanin synthesis is temporarily decreased or stopped by reduced sunlight exposure, leading to the appearance of hypopigmented macules.

There are many follow-up reports of PMH. Guillet et al.1 suggested that hypopigmented lesions spontaneously decrease after 2~5 years. In the present study, we followed 3 patients who did not receive treatment for 3 months to 8.33 years. Only one of those patients improved, with a time-to-repigmentation of 8.33 years (Table 3). More extensive follow-up is needed to confirm the spontaneous resolution of PMH.

Topical and systemic antifungal agents, topical steroids, topical antimicrobial agents, and PUVA therapy have been used to treat PMH; however, no consistently effective therapy has been established. Relyveld et al.10 compared the effectiveness of antimicrobial therapy (5% benzoyl peroxide hydrogel/1% clindamycin lotion) with anti-inflammatory therapy (0.05% fluticasone cream) in patients with PMH. Relyveld et al.10 concluded that antimicrobial therapy with light was a more effective treatment modality, which supports the hypothesis of Westerhof et al.9 that P. acnes is causally related to PMH. Kim et al.6 reported that one Korean patient improved after NBUVB phototherapy. Although topical antimicrobial therapy was not used in that study, one of our patients improved after taking an antimicrobial agent (minocycline hydrochloride; Table 3). However, this patient stopped treatment on his own volition after taking oral minocycline for only 1 month, and repigmentation developed after 1 year. Similarly, the one patient who showed repigmentation after treatment with a topical drug had stopped using 1% hydrocortisone lotion after only 4 months, and repigmentation developed after 40 months. Therefore, it is difficult to conclude if a successful outcome was achieved with minocycline hydrochloride or topical steroid application. In contrast, six patients treated with NBUVB phototherapy showed marked repigmentation, and hypopigmented lesions did not recur during 3~13 months of follow-up. Therefore, we suggest that NBUVB phototherapy is an effective treatment for PMH. In a previous study, NBUVB phototherapy was shown to promote melanocyte proliferation and migration and to diminish the activation of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α, which suppress melanin synthesis11,12. This resulted in repigmentation of the hypopigmented lesions.

In conclusion, patients presenting with acquired, non-scaly, confluent, hypopigmented macules on the trunk should be evaluated using KOH mounts, Wood's lamp examination, or skin biopsies to rule out other hypopigmented diseases. Moreover, a special diagnosis of PMH should be considered. In Korean PMH patients, the most frequently affected sites were the back and abdomen, with a reduced occurrence on the buttocks and chest. Histologically, the number of S-100-positive melanocytes did not differ significantly between the hypopigmented macules and normal perilesional skin. No effective treatment is known for PMH; however, NBUVB phototherapy may be useful. This is the first clinicopathologic study of PMH in Koreans. Additional studies with greater numbers of patients are necessary to certify the clinical characteristics, histologic findings, and therapeutic outcomes of PMH in Koreans.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 2Case 12. (A) Ill-defined confluent, non-scaly hypopigmented patch with scattered macules are noted on the back. (B) Hypopigmented lesions were successfully treated after nine sessions of narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy. |

| Fig. 3Case 17. The biopsy obtained from the hypopigmented lesion (A) shows less melanin granules in the basal layer than normal skin (B) (H&E, ×100). |

| Fig. 4Case 13. There was no difference in the number of S-100 protein-positive cells between the hypopigmented macule (A) and perilesional normal-appearing skin (B) (S-100 protein, ×400). |

References

1. Guillet G, Helenon R, Gauthier Y, Surleve-Bazeille JE, Plantin P, Sassolas B. Progressive macular hypomelanosis of the trunk: primary acquired hypopigmentation. J Cutan Pathol. 1988. 15:286–289.

2. Borelli D. Cutis "trunci variata." A new genetic dermatosis. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am. 1987. 15:317–319.

3. Lesueur A, Garcia-Granel V, Helenon R, Cales-Quist D. Progressive macular confluent hypomelanosis in mixed ethnic melanodermic subjects: an epidemiologic study of 511 patients. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1994. 121:880–883.

4. Sober AJ, Fitzpatrick TB. The year book of dermatology 1996. 1996. St. Louis: Mosby;407–416.

5. Choi YJ, Hann SK. Two cases of progressive macular hypomelanosis of the trunk. Korean J Dermatol. 2000. 38:655–658.

6. Kim BD, Chung YL, Lee GS, Hann SK. A case of progressive macular hypomelanosis treated with narrow band UVB. Korean J Dermatol. 2003. 41:1664–1666.

7. Kumarasinghe SP, Tan SH, Thng S, Thamboo TP, Liang S, Lee YS. Progressive macular hypomelanosis in Singapore: a clinico-pathological study. Int J Dermatol. 2006. 45:737–742.

8. Relyveld GN, Dingemans KP, Menke HE, Bos JD, Westerhof W. Ultrastructural findings in progressive macular hypomelanosis indicate decreased melanin production. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008. 22:568–574.

9. Westerhof W, Relyveld GN, Kingswijk MM, de Man P, Menke HE. Propionibacterium acnes and the pathogenesis of progressive macular hypomelanosis. Arch Dermatol. 2004. 140:210–214.

10. Relyveld GN, Kingswijk MM, Reitsma JB, Menke HE, Bos JD, Westerhof W. Benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin/UVA is more effective than fluticasone/UVA in progressive macular hypomelanosis: a randomized study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006. 55:836–843.

11. Kim HS, Park HH, Lee MH. Identification of UVB effects on gene expressed by normal human melanocytes. Korean J Dermatol. 2003. 41:1597–1602.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download