Abstract

Background

Acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules (ABNOM) is a dermal pigmented lesion common in individuals of Oriental origin. The Q-switched Nd:YAG laser (QSNYL) has been used successfully to treat a variety of benign, dermal, pigmented lesions, including nevus of Ota lesions. The similarity between ABNOM and nevus of Ota suggested that QSNYL may also be effective in the former.

Objective

To determine the efficacy and side-effect profiles of QSNYL treatment of ABNOM in Korean patients.

Methods

Of 42 Korean patients with ABNOM, 29 were treated with QSNYL (1,064 nm, 3 mm spot size, fluence 8~9.5 J/cm2), for up to 10 sessions each. Clinical photographs were taken before and after treatment. Lesion clearance was graded and complications such as hyperpigmentation, scarring, hypopigmentation, and erythema were assessed.

Results

Of the 29 treated patients, 19 (66%) showed excellent or good results. Of the patients who were treated more than 3 times, 76% showed good to excellent results. Two patients experienced post-laser hyperpigmentation (PLH), which persisted for more than one month, but no patient experienced persistent erythema or hypertrophic scarring.

Acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules (ABNOM), a circumscribed dermal melanocytosis of the face, is fairly common in non-Caucasians, including Koreans and Japanese. ABNOM appears as small, bilateral, blue-brown and/or slate-gray patches on the forehead, temples, eyelids, malar areas, and alae and roots of the nose1. In the literature, several modalities of treatment, including cryotherapy2 and dermabrasion3 have been tried for ABNOM. Based on the principles of selective photothermolysis, nevus of Ota has been successfully treated with Q-switched ruby lasers4,5, Q-switched alexandrite lasers6, and Q-switched Nd:YAG lasers (QSNYL)7. The histological similarities between ABNOM and nevus of Ota suggested that laser therapy may also be successful in the treatment of ABNOM. We therefore assessed the efficacy and side-effect profiles of QSNYL in the treatment of Korean patients with ABNOM.

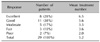

Our study cohort consisted of 42 individuals (40 women, 2 men) with a clinical diagnosis of ABNOM. None of these patients had received any previous treatments for their lesions. Mean patient age at the first visit was 33.4 years (range, 22 to 52 years). Color of lesions was classified into 3 categories: brown, slate-gray, and blue. All 42 patients had lesions on the zygomatic area, which appeared as mottled brownish-to-bluish macules. Lesions were also observed on the temporal area (12/42, 28%), forehead (4/42, 10%), upper eyelids (3/42, 7%) and nose (2/42, 5%) (Table 1).

A total of 29 of the 42 patients were treated with a QSNYL, at a wavelength of 1064 nm, a pulse duration of 5~7 nsec, a spot size of 3 mm, and a fluence of 8~9.5 J/cm2. For all patients we applied topical anesthesia (a eutectic mixture of 2.5% lidocaine HCl and 2.5% prilocaine, EMLA). The therapeutic endpoint was defined as immediate whitening following laser irradiation. Energy densities were reduced if tissue bleeding was prominent. Patients were treated up to 10 times, at intervals ranging from 4 to 12 weeks depending on the degree of post-laser hyperpigmentation (PLH). After each laser session, all patients applied topical mupirocin ointment and sunblocking agents. Depigmentary cream, such as 4% hydroquinone creams, was applied when PLH occurred. The patients were instructed to keep away from the sun.

Responses to laser treatment were clinically assessed by two independent dermatologists using clinical photographs taken at each follow-up visit. Photographs were obtained from the front and side of both cheeks at every visit. The same photographer took these with the same digital camera (D70, Nikon, Japan) and ambient lighting. Responses to treatment were assessed according to the percentage pigment clearing and were classified as excellent (lightening of 75~100%), good (lightening of 50~74%), moderate (lightening of 25~49%), fair (lightening of 10~24%), and poor (lightening of less than 9%). If there was a discrepancy between two observers, the degree of improvement was graded according to the lower score. We evaluated the effects of number of treatment, color of lesions and site of lesions on therapeutic outcomes. Any side effects such as scarring, hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation and erythema were also assessed at each visit.

Spearman correlation analyses were performed to determine the significance of number of treatment, color of lesions and site of lesions. The correlation between the color of lesions and PLH was determined using the Chi-square test for trends. Inter-observer agreement was analyzed by the Kappa statistics. All analyses were performed using SPSS, version 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

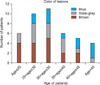

Of the 16 patients younger than 30 years, 8 showed brown-colored lesions and 2 revealed blue-colored macules. In contrast, 5 of 9 patients older than 40 years had blue-colored lesions (Fig. 1). According to Spearman's correlation analysis, lesions tended to become progressively bluer with age (correlation coefficient, r=0.339, p=0.028).

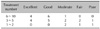

The Kappa statistic revealed a significant agreement between the two assessments (Kappa=0.904, p<0.001). The data collected are summarized in Table 2. Of the 29 treated patients, 19 (66%) showed excellent or good results (Table 3, Fig. 2, 3); 76% who were treated more than three times had good or excellent result (Table 4). Of patients who were treated more than six times, 90% demonstrated good or excellent results. The average number of treatment sessions for patients with excellent results was 6.5, compared with 2.0 for patients with moderate results. There was a statistically significant correlation between the number of treatments and therapeutic outcomes (r=0.484, p=0.008). Good or excellent results were observed in 55% of patients with bluecolored lesions, 73% with slate-gray colored lesions and 71% with blue-colored lesions (Table 5). Statistically, therapeutic outcome was not dependent on the color or site of lesions. Post-laser erythema, lasting 1 day to 2 weeks, was observed in all patients. Twelve patients (40%) developed transient PLH, which generally faded 1~4 weeks after treatment. Four of 11 patients with brown-colored lesions developed transient PLH (Fig. 4). However, a significant correlation between color and transient PLH was not demonstrated (p=0.869 by Chi-square test for trend). PLH persisted for more than one month in two patients who presented with brown-colored macules (Fig. 5). There were no cases of persistent erythema, hypertrophic scarring, or persistent textural changes.

ABNOM, a pigmentary disorder first described in 19841, usually begins as discrete brown macules; these become confluent, slate-gray macules over time8. The malar region of the cheek is the most commonly affected area. It is important to clinically and histologically differentiate ABNOM from nevus of Ota, female facial melanosis, and melasma. ABNOM is an acquired disease, usually appearing during the fourth or fifth decades of life, and is usually bilateral. In contrast, nevus of Ota usually develops during the first year of life or during adolescence, is usually unilateral and involves the conjunctival, oral or nasal mucosae, as well as the tympanic membrane. Although dermabrasion has been successful in the treatment of ABNOM3, this procedure is highly invasive and is associated with many complications, including scarring, infection and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. Therefore, QS lasers are the main treatment modalities for ABNOM as well as for nevus of Ota. In a previous report, of patients undergoing 2~7 QSNYL treatment sessions at intervals of 2 to 6 months, 30~100% showed a greater than 50% lightening response and the incidence of PLH ranged from 50~100%, with differences in clinical responses due to differences in laser parameters and treatments intervals9-11. In our study, 66% of treated patients and 76% of patients who were treated more than three times showed greater than 50% of clearing and only 40% had transient PLH. We found a statistically significant correlation between the number of treatments and therapeutic outcome. This means that clinicians need to consider repeated treatments for resolving ABNOM. We found no color or site-dependent differences in therapeutic outcomes. In contrast to several previous protocols, our repetitive treatment sessions were performed at 1- to 3-month intervals. This short interval time was chosen to improve the rate of clearing and prevent epithelial repigmentation. Epidermal melanin and melanocytes are competing chromophores for dermal pigment laser therapy and increase the risk of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. By performing treatment sessions at short intervals, more photons can target the dermal chromophores through the hypopigmented epithelium while avoiding scattering of the beam12. In addition, heat has little effect on the hypopigmented epidermis, thereby preventing PLH13.

Histologically, in ABNOM dermal melanocytes are scattered throughout the upper and middle portions of the dermis, whereas, in nevus of Ota melanocytes are diffused throughout the entire dermis1. In addition, ABNOM is characterized by prominent epidermal hypermelanosis together with dermal melanophages. Variations in color (brown, gray, blue) are due to the proportion of pigmented cells in the epidermis and dermis14. Although the pathogenesis of ABNOM is unclear, it may be due to "epidermal melanocyte migration"1. This mechanism is consistent with the fact that the color of the macules varies with the maturity of the ABNOM. Initially, these macules are usually brown and discrete, becoming bluish-gray and diffuse over time. The early-stage brown lesions are thought to be due to the presence of melanocytes at the basal layer of the epidermis; their subsequent migration into the dermis leads to a darker bluish-gray color8,14. Although we found no color-dependent differences in the development of transient PLH, two patients with brown macules experienced PLH that persisted for more than 1 month. In agreement with the epidermal migration hypothesis, early-stage brown lesions have more epidermal melanosis, and PLH is more likely to occur in epidermis that contains abundant melanin. Moreover, melanocytes in ABNOM contain immature melanosomes, which are at stage II melanization2. In cases of early-stage brown ABNOM, there are more melanocytes with immature melanosomes, and laser treatment may fail to destroy these amelanotic melanocytes; this may activate immature melanocytes, leading to PLH15. Thus, care should be taken when treating patients with early-stage disease. Epidermal melanin in these lesions can be destroyed using an adjuvant modality such as a 532 nm QSNYL, a CO2 laser or bleaching agents14,16,17.

In conclusion, we have shown here that QSNYL 1064 nm is effective in the treatment of ABNOM. Repeated treatments separated by short time intervals can improve therapeutic results and reduce PLH. In addition, early-stage brown macules are more likely to produce PLH.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Color of lesions according to the age of patients. Lesions tended to become progressively bluer with age.

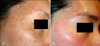

Fig. 2

(A) A 27-year-old female with ABNOM before treatment. (B) Improvement in ABNOM after three QSNYL treatments. Results were excellent, with a 75~100% reduction in color.

Fig. 3

(A) A 53-year-old female with ABNOM before treatment. (B) Improvement of ABNOM after five QSNYL treatments. Results were excellent, with a 75~100% reduction in color.

Fig. 5

Treatment-related worsening in a 34-year-old woman with early-stage brown macules. (A) Before treatment. (B) Worsening of ABNOM after one QSNYL treatment.

References

1. Hori Y, Kawashima M, Oohara K, Kukita A. Acquired, bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984. 10:961–964.

2. Hori Y, Takayama O. Circumscribed dermal melanoses. Classification and histologic features. Dermatol Clin. 1988. 6:315–326.

3. Kunachak S, Kunachakr S, Sirikulchayanonta V, Leelaudomniti P. Dermabrasion is an effective treatment for acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules. Dermatol Surg. 1996. 22:559–562.

4. Goldberg DJ, Nychay SG. Q-switched ruby laser treatment of nevus of Ota. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992. 18:817–821.

6. Alster TS, Williams CM. Treatment of nevus of Ota by the Q-switched alexandrite laser. Dermatol Surg. 1995. 21:592–596.

7. Chan HH, Ying SY, Ho WS, Kono T, King WW. An in vivo trial comparing the clinical efficacy and complications of Q-switched 755 nm alexandrite and Q-switched 1064 nm Nd:YAG lasers in the treatment of nevus of Ota. Dermatol Surg. 2000. 26:919–922.

8. Ee HL, Wong HC, Goh CL, Ang P. Characteristics of Hori naevus: a prospective analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2006. 154:50–53.

9. Suh DH, Han KH, Chung JH. Clinical use of the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser for the treatment of acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules (ABNOMs) in Koreans. J Dermatolog Treat. 2001. 12:163–166.

10. Kunachak S, Leelaudomlipi P. Q-switched Nd:YAG laser treatment for acquired bilateral nevus of ota-like maculae: a long-term follow-up. Lasers Surg Med. 2000. 26:376–379.

11. Polnikorn N, Tanrattanakorn S, Goldberg DJ. Treatment of Hori's nevus with the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser. Dermatol Surg. 2000. 26:477–480.

12. Manuskiatti W, Fitzpatrick RE, Goldman MP. Treatment of facial skin using combinations of CO2, Q-switched alexandrite, flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye, and Er:YAG lasers in the same treatment session. Dermatol Surg. 2000. 26:114–120.

13. Lee B, Kim YC, Kang WH, Lee ES. Comparison of characteristics of acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules and nevus of Ota according to therapeutic outcome. J Korean Med Sci. 2004. 19:554–559.

14. Ee HL, Goh CL, Khoo LS, Chan ES, Ang P. Treatment of acquired bilateral nevus of ota-like macules (Hori's nevus) with a combination of the 532 nm Q-Switched Nd:YAG laser followed by the 1064 nm Q-switched Nd:YAG is more effective: prospective study. Dermatol Surg. 2006. 32:34–40.

15. Lam AY, Wong DS, Lam LK, Ho WS, Chan HH. A retrospective study on the efficacy and complications of Q-switched alexandrite laser in the treatment of acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules. Dermatol Surg. 2001. 27:937–941.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download