Abstract

Aplasia cutis congenita (ACC) is a rare congenital defect in which localized or widespread areas of the skin are absent at birth. In the majority of cases, it is limited to the scalp especially on the vertex although other areas of the body may also be involved. Other congenital malformations can be associated with ACC. We present herein the case of a new born male with unilateral absence of skin on the extensor surface of the right lower leg. There was no associated malformation or skin disease such as blistering or nail abnormailty. According to the classification outlined by Frieden, the condition was diagnosed as type VII aplasia cutis congenita. The treatment of this large ulcer was conservative, wet dressing and prophylactic topical antibiotics. On follow up after 2 years showed that the patient was nearly cured of the ulcer and had only minimal scar formation.

Aplasia cutis congenital (ACC) is defined as a localized or widespread absence of skin at birth. As it was first described by Cordon1 in 1967, the lesions usually appear as circular oval, sharply outlined ulcer, which result in scarring after they are healed. Almost 80% of aplasia cutis appears in the scalp regions, and only about 10~15% of ACC involve other areas of the body. In some cases, the lesions can be a sign of embryonic malformation, chromosomal abnormality, or ectodermal dysplasia. Moreover, association with epidermolysis bullosa, intrauterine infection, or specific teratogens has been described. Defects of the skin limited to the lower limbs are very rare. The defects are usually presented as ulcerations, membranous lesions, or areas of atrophic scarring.

We report an unusual case of ACC with full thickness skin defect located only on the right lower leg.

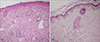

A newborn male presented with a large ulcer on the right leg which had been present since birth. There was no significant antenatal or family history. The mother had no specific disease or drug history prior to or during the pregnancy. He was born through normal vaginal delivery at 39 weeks' gestation with a weight of 3.4 kg. On physical examination, a large ulcer was found, with a length of about 20 cm on the right leg from the knee area to the medial dorsal foot (Fig. 1). The toenails, teeth and mucosa of the mouth were not affected, and there was no blistering anywhere on the body. The routine laboratory results were within normal limits and the serologic analysis for TORCH yield negative results. A punch biopsy taken from the ulceration on the thigh 5 days after birth showed the absence of epidermis and inflammatory infiltrate as well as proliferation of blood vessels in the dermis (Fig. 2). There was no evidence of a hemangioma or variant malformation and the histologic pattern resembled nonspecific granulation tissue. Furthermore, the results of the direct immunofluorescence test using IgG, IgA, C3 antibody were normal. Initially the ulceration appeared shiny, red and was translucent with good visible blood vessels. 15 days later, hyperproliferative granulation tissue developed and blood clots were observed (Fig. 3). To avoid infection we applied mupirocin ointment and wet petroleum gauze dressings. A follow up of the patient 2 years later revealed only minimal atrophic scar formation. The function of the right leg was nearly normal and there was no limb reduction. The infant's mental and physical development has been normal.

The patient was diagnosed with ACC, according to the clinical, histologic features and course of the disease. About 80% of ACC cases involve the scalp. Less often, the affected areas include the forearms, knees, trunk, legs and face. The condition encompasses a heterogeneous group of disorders with or without associated abnormal physical findings, malformation patterns, genetic disease, or a combination of these. Frieden2 and Sybert3 have proposed the classification of ACC on the basis of its associated abnormalities and inheritance patterns.

The etiopathogenesis of ACC remains unclear. Several theories have been suggested in an attempt to explain the cause4. The vascular theory suggests that there is vascular insufficiency to the skin, perhaps from placental compromise or a thromboplastic material56. Another accepted theory is that the early rupture of the amniotic membrane was the origin of the process. Such a rupture would permit fluid leakage, leading to the introduction of the fetus into the chorionic cavity7. The Chorion will reabsorb this fluid, stimulating the proliferation of mesenchymal bands that envelop and compress the fetal structures, giving rise to malformation of variable severity depending on the degree of embryologic development8.

Histopathological findings are nonspecific9. The epidermis is either missing or consists of a few epidermal cell layers. The underlying dermis is thin and is composed of loosely arranged collagen bundles in which there is some disarray of collagen fibers. The dermis may resemble a scar. Appendages are absent or rudimentary and the subcutis is usually thin.

We should consider an association with epidermolysis bullosa type VI. One case of a pretibial aplasia cutis has been described in the literature, but this patient developed bullae and violaceous lichenoid papules and plaques10. The patient in this case, however, had no signs of epidermolysis bullosa, and there was no blistering or fragility of the skin. Even the follow up after 2 years did not show any clinical sign of underlying epidermolysis bullosa.

Aside from other differential type of ACC, we made a distinction with drug-induced ACC, Adams-Oliver syndrome, Bart syndrome, and traumatic origin ulceration. As there were no signs of syndactyly or transverse nail dystrophy and no defects in the central nervous system, Adams-Oliver syndrome, an ACC with transverse limb defects11, can be excluded. Bart syndrome which was first described by Bart in 1996, has to be considered; it represents the combination of congenital epidermolysis bullosa, congenital localized absence of skin affecting the extremities, and shedding or dystrophy of the nails12. It sometimes also involves the oral mucous membrane13. Our patient did not have any nail abnormality or mucus membranes involvement.

When ACC occurs as a small, focal scalp ulcer, it heals spontaneously. In the case of the large lesion with or without underlying tissue and associated with exposed dura or sagittal sinus, prompt intervention should be considered. While some evidence exists to support conservative dressing and the avoidance of active surgical intervention, several cases of dramatic and often fatal sagittal sinus hemorrhage associated with a large full thickness scalp and skin defects over the sagittal sinus have been reported. Therefore, consultation with the surgical department, such as neurosurgery, is of critical importance in the treatment of these patients. After our patient was given conservative treatment with prophylactic topical antibiotics and wet dressing, the ulcer was healed with atrophic scar formation.

In conclusion, localization in the pretibial area of the right limb and the absence of associated malformation suggests that our case should be classified as type VII of the classification according to Frieden. Almost all previously reported cases141516171819 had scalp ACC. However our case is limited to unilateral lower extremities. This is the first case of ACC on the leg without association with epidermolysis bullosa in Korea. The follow-up after nearly 2 years showed a very favorable outcome, with little scar formation and no functional impairment of the leg.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Large ulcer about 20 cm length along the right leg without nail dystrophy. On the day of birth. Arrow indicates biopsy site.

References

1. Corden M. Extrait d'une letter au sujet de trios enfants de la meme nes avee partie des extremities denuee de peau. J Med Chir Pharmacie. 1767; 26:556–557. Cited from reference 2.

2. Frieden IJ. Aplasia cutis congenital: a clinical review and proposal of classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986; 14:646–660.

3. Sybert VP. Aplasia cutis congenita: a report of 12 new families and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1985; 3:1–14.

4. Kelly BJ, Samolitis NJ, Xie DL, Skidmore RA. Aplasia cutis congenita of the trunk with fetus papyraceus. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002; 19:326–329.

5. Mannino FL, Jones KL. Benirschke: Congenital skin defects in fetus papyraceus. J Pediatr. 1997; 4:559–564.

6. Fusi L, McParland P, Fisk N, Nicolini U, Wigglesworth J. Acute twin-twin transfusion: A possible mechanism for brain-damaged survivors after intrauterine death of a monochronic twin. Obstet Gynecol. 1991; 78:517–520.

7. Torpin R. Amniochronic mesoblastic fibrous strings and amniotic bands. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1965; 91:65–75.

8. Light TR, Ogden JA. congenital constriction band syndrome. Pathophysiology and treatment. Yale J Biol Med. 1993; 66:143–155.

9. Weedon D. Skin pathology. 1st ed. New York: Churchill-Livingstone;1997.

10. Bridges AG, Mutasim DF. Pretibial dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Cutis. 1999; 63:329–332.

11. Mempel M, Abeck D, Lange I, Stom K, Calibe A, Beham A, et al. The wide spectrum of clinical expression in Adams-Oliver syndrome; a report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 1999; 104:1157–1160.

12. Gutzmer R, Herbst RA, Becker J. Bart syndromeseparate entity or a variant of epidermolysis bullosa? Hautarzt. 1997; 48:640–644.

13. Gharpuray MB, Tolat SN, Patki AH. Congenital localized absence of skin associated with blistering of the skin and mucous membrane; Bart's syndrome. Cutis. 1989; 44:318–320.

14. Park SH. A case of aplasia cutis congenita. Korean J Dermatol. 1984; 22:346–349.

15. Choi HM, Myung KB, Kook HI. Two cases of aplasia cutis congenita. Korean J Dermatol. 1985; 23:83–87.

16. Chung J, Lee WS, Ahn SK. Aplasia cutis congenita. Korean J Dermatol. 1994; 32:698–702.

17. Park JM, Kim YS, Kwon SJ, Yu HJ, Park YW. A case of aplasia cutis congenita. Korean J Dermatol. 2000; 38:295–297.

18. Mo HJ, Park CJ, Yi JY. A case of aplasia cutis congenita. Korean J Dermatol. 2001; 39:612–614.

19. Park G, Kim HJ, Jang HC, Chung H. A case of aplasia cutis congenita after methimazole exposure during pregnancy. Korean J Dermatol. 2006; 44:642–644.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download