Abstract

Acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma is a well-defined variant of squamous cell cancer in which significant portions of the neoplastic proliferation show a pseudoglandular or tubular microscopic pattern. It usually presents as a nodule with various colors, and it is accompanied by scaling, crusting, and ulceration on the sun-exposed areas of older aged individuals. Histologically, the tumor consists of a nodular, epidermal-derived proliferation that forms island-like structures. At least focally or sometimes extensively, the tumor cells shows a loss of cohesion within the central gland-like or tubular spaces. This tumor resembles the structure of eccrine neoplasms, but it is negative for dPAS, CEA and mucicarmine and it is only positive for EMA and cytokeratins. Herein we report a case of acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma that occurred on the face of an 82-year-old woman.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common type of skin cancer and it has several subtypes that have varying clinical behavior and malignant potential1. Acantholytic SCC (A-SCC) is the uncommon variant of SCC in which significant portions of the neoplastic proliferation show a pseudoglandular or tubular pattern2. It resembles the structures of eccrine neoplasms, but it is negative for dPAS, CEA, and mucicarmine and it is only positive for EMA and cytokeratins (CKs)1 . The prognosis of A-SCC remains controversial, but at present it is best considered to be SCC of an intermediate risk12. Herein we report a case of acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma that occurred on the face of an 82-year-old woman.

An 82-year-old woman presented with an erythematous nodule on the left eyebrow with a 4-months-history. The patient was on medication for hypertension, but otherwise healthy without any other systemic diseases. She had a history of Mohs micrographic surgery for SCC on the right cheek 2 months previously. On examination, a non-inflamed slightly pruritic hyperkeratotic papule with tenderness was located on the left eyebrow (Fig. 1). Clinically prurigo nodularis, seborrheic keratosis, and SCC were suspected and then a shaving biopsy was performed for making the diagnosis.

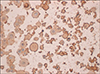

Histologic examination revealed that the tumor was composed of epidermal-derived cystic structures. The central spaces contained floating individual acantholytic cells and atypical dyskeratotic cells (Fig. 2A). At the periphery of the tumor, the cells formed a cohesive layer that was one to two cells thick. The acantholytic cells appeared extremely bizarre, large, and multinucleated (Fig. 2B). On the immunohistochemical studies, the acantholytic tumor cells were negative for dPAS, mucicarmine, and CEA staining and they were positive for CKs with a crisp cytoplasmic staining pattern (Fig. 3).

The whole lesion was removed after skin biopsy and no recurrence was noted for 6 months.

SCC is an uncommon variant of SCC that was first described by Lever in 1947 as adenoacanthoma of the sweat glands3. It was also known as adenoid SCC, lobular SCC, or pseudoglandular SCC4567. As can be guessed by the name, it was previously thought to be a tumor of a sweat gland origin because of gland-like and solid epithelial proliferations extending into the dermis3. However, A-SCC is now accepted as a distinct variant of SCC rather than a sweat gland tumor8.

Clinically, A-SCC is usually found on the sunexposed areas of elderly patients with notable male predominance. It presents most often on the head and neck, but other sites of origin have been reported, including the vulva, penis, oral mucosa, nasopharynx, and breast1910111213. It appears as flesh-colored, pink, red, or brown nodules in most cases, and it is frequently accompanied by scaling, crusting, and ulceration like the other SCC variants. Therefore, histological examination is necessary for making the accurate diagnosis.

Histologically, the tumor is composed of a epidermal-derived cystic proliferation extending into the dermis, and this forms lobules or nests, columns and island-like structures15. Many of the tumor strands exhibit tubular and gland-like structures due to the loss of intercellular cohesion, which is referred to as a "pseudoglandular" appearance. Within the central spaces, there are many floating individual acantholytic cells that show atypical dyskeratosis. These acantholytic cells appear extremely bizarre, large, and multinucleated. Slightly basophilic amorphous material can sometimes be seen within the central spaces, and this material has a suspected glandular origin. But the tumor is negative on both dPAS and mucicarmine staining, and this is unlike other eccrine neoplasms156714. The overlying epidermis may show hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis, and the connection to the underlying tumor can be seen in most cases12.

Although classic type SCC may also show some clefts with dyskeratosis and acantholysis, it does not have a definite wall or a cohesive layer of cells surrounding the acantholytic cells, as is seen in A-SCC25. Some authors have suggested the hypothesis that A-SCC originates from premalignant acantholytic actinic keratosis5. However, clinically it can occur on sun-protected areas and histologically there may be no sign of solar damage57815. In addition, Nappi et al14 did not find the exact association between A-SCC and acantholytic actinic keratosis in their 55 cases. According to these reasons, it is now thought that acantholytic actinic keratosis is not the precursor lesion of A-SCC. Although there are no specific risk factors for A-SCC, it is supposed that other predisposing factors for SCC, including immunosuppression, scars, burns and human papillomavirus infection as well as ultraviolet radiation, may be involved in the development of this tumor. It has been documented to arise in areas of pre-existing scarring and in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia81014.

The histopathologic differential diagnosis includes adenoid basal cell carcinoma (BCC), eccrine adenocarcinomas, metastatic adenocarcinomas, and epithelioid angiosarcomas56714. BCC must show, at least in part, the typical peripheral palisading, peritumoral lacunae, and stromal mucin. Most eccrine neoplasms are positive for S-100, EMA, CEA, and CKs, while A-SCC stains positive for only EMA and CKs. Epithelioid angiosarcoma shows positivity for endothelial markers. Metastatic adenocarcinoma shows multiplicity, acantholytic dyskeratosis and the absence of clear epidermal attachments141617.

According to the study by Nappi et al14 in 1989, 11 patients had local recurrence, 5 had visceral metastases, and 2 died of local intracranial extension of the tumor in their review of 36 patients, and the total mortality was 19%. It is thought this high mortality rate may have been due to refusal of treatment or a reporting bias. In a more recent study by Petter and Haustein18 in 1998, only 1 patient developed a local recurrence. There are some reasons for the difficulty to evaluate the metastatic potential of A-SCC. First, there are no precise clinical data about the size of the lesiones. Second, most of the reported lesions located on mucosa to have a high malignant potential. Third, many patients have predisposing factors associated with metastasis (i.e., immunosuppression)3567891011121314. Although various reports have shown controversial results, the overall malignant potential of A-SCC seems not to be higher than that of typical invasive SCC12.

A-SCC is an uncommon variant of SCC and it has a characteristic 'pseudoglandular' appearance, so making the differential diagnosis via immunohistochemistry to exclude eccrine neoplasms and vascular sarcomas may be important. Herein we report a case of A-SCC that showed well-defined cystic structures, confirmed by immunohistochemical staining.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Cassarino DS, Derienzo DP, Barr RJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification. Part one. J Cutan Pathol. 2006; 33:191–206.

2. Kane CL, Keehn CA, Smithberger E, Glass LF. Histopathology of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and its variants. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2004; 23:54–61.

3. Lever WF. Adenoacanthoma of sweat glands: carcinoma of sweat glands with glandular and epidermal elements: report of 4 cases. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1947; 56:157–171.

4. Lohmann CM, Solomon AR. Clinicopathologic variants of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Adv Anat Pathol. 2001; 8:27–36.

5. Johnson WC, Helwig EB. Adenoid squamous cell carcinoma (adenoacanthoma). A clinicopathologic study of 155 patients. Cancer. 1966; 19:1639–1650.

6. Muller SA, Wilhelmj CM Jr, Harrison EG Jr, Winkelmann RK. Adenoid squamous cell carcinoma (adenoacanthoma of Lever). Arch Dermatol. 1964; 89:589–597.

7. Underwood JW, Adcock LL, Okagaki T. Adenosquamous carcinoma of skin appendages (adenoid squamous cell carcinoma, pseudoglandular squamous cell carcinoma, adenocanthoma of sweat gland of Lever) of the vulva: a clinical and ultrastructural study. Cancer. 1978; 42:1851–1858.

8. Toyama K, Hashimoto-Kumasaka K, Tagami H. Acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma involving the dorsum of the foot of elderly Japanese: clinical and light microscopic observations in five patients. Br J Dermatol. 1995; 133:141–142.

9. Lasser A, Cornog JL, Morris JM. Adenoid squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Cancer. 1974; 33:224–227.

10. Watanabe K, Mukawa A, Miyazaki K, Tsukahara K. Adenoid squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. Report of a surgical case clinically manifested with rapid lung metastasis. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1983; 33:1243–1250.

11. Takagi M, Sakota Y, Takayama S, Ishikawa G. Adenoid squamous cell carcinoma of the oral mucosa: report of two autopsy cases. Cancer. 1977; 40:2250–2255.

12. Zaatari GS, Santoianni RA. Adenoid squamous cell carcinoma of the nasopharynx and neck region. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986; 110:542–546.

13. Eusebi V, Lamovec J, Cattani MG, Fedeli F, Millis RR. Acantholytic variant of squamous-cell carcinoma of the breast. Am J Surg Pathol. 1986; 10:855–861.

14. Nappi O, Pettinato G, Wick MR. Adenoid (acantholytic) squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1989; 16:114–121.

15. Petter G, Haustein UF. Histologic subtyping and malignancy assessment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2000; 26:521–530.

16. Tot T. Cytokeratins 20 and 7 as biomarkers: usefulness in discriminating primary from metastatic adenocarcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2002; 38:758–763.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download