Abstract

The idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) represents a leukoproliferative disorder, characterized by unexplained prolonged eosinophilia (>6 months) and evidence of specific organ damage. So far, the peripheral neuropathy associated with skin manifestations of HES has not been reported in the dermatologic literature although the incidence of peripheral neuropathy after HES ranges from 6~52%. Herein, we report the peripheral neuropathy associated with HES, documented by clinical, histopathological, and electrodiagnostic criteria.

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) represents a heterogenous group of disorders with idiopathic prolonged eosinophilia and evidence of organ involvement. Patients determined as HES should fulfill several diagnostic criteria. First, sustained blood eosinophilia at least 1,500/L must be present longer than 6 months. Second, patients must have signs and symptoms of multiorgan involvement. Third, no other apparent causes of eosinophilia must be present, including parasitic or allergic disease or other known causes of peripheral blood eosinophilia1.

HES is a multisystem disorder most often affecting the heart, lungs, skin, and central and peripheral nervous system. Although it has a relatively high frequency, the pathogenesis and natural history ofperipheral neuropathy associated with HES with and without treatment has been poorly defined2.

In this paper, we report a case of HES in a 16-year-old male, who showed cutaneous and neurologic manifestations initially, and improvement after treatment with corticosteroids.

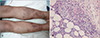

A 16-year-old boy exhibited pruritic indurated plaques and papules on the lower extremities (Fig. 1A) for 15 days; He complained of tingling sensation and a mild weakness in his left leg and right arm. A skin biopsy from the individual leg revealed numerous eosinophils in the perivascular and periadnexal inflammatory infiltrate, and subcutis (Fig. 1B). Laboratory data revealed that the white blood cell count was 14,200 per mm3 with 31% eosinophils. A peripheral blood smear showed a marked eosinophilia. On the other hand, normal results were found from the liver and renal function test. The creatine phosphokinase isoenzyme level was within normal range. The total IgE level was greater than 2,500 IU/mL. The electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, chest X-ray, pulmonary function test, abdominal ultrasonography, and ophthalmological examination were normal. There was no evidence of a parasitic infestation from the stool examination and serologic tests. We suspected eosinophilic cellulites and started the treatment with 60 mg prednisolone daily. Within 5 days, his eosinophil count returned to 3% and the itching sensation subsided. However, the sensory and motor disturbances still remained. The neuropathy was documented by nerve conduction studies and electromyography (EMG), which revealed reduced amplitude of the sensory and motor evoked responses and slowed conduction velocities that were consistent with mononeuritis multiplex.

After 5 months abdominal pain developed and the white blood cell count was 24,800 per mm3 with 60% eosinophils; the patient was admitted to the department of pediatrics. Abdominal pain subsided with only conservative treatment in two days and abdominal ultrasonography was normal. From June 2005 to April 2006, his eosinophil count remained at more than 40%. The patient demonstrated a prolonged period (>6 months) of hypereosinophilia but lacked evidence of parasitic, allergic, or any other recognized cause of eosinophilia, or symptoms and signs of the skin and peripheral nervous system involvement. This fulfilled the criteria for HES.

During the follow-up periods, the skin lesion had waxed and waned regardless of the low dose maintenance steroid therapy. Six months later, the results of his neurologic examination were much improved, with manual muscle testing after rehabilitation and physical therapy. In addition, his eosinophil count level had somewhat decreased, though still elevated.

The peripheral neuropathy associated with HES has been documented with increased frequency but little is known about its natural history. Neurological symptoms may be the primary manifestations in HES. A variety of neuropathy has been described, including multiple mononeuropathy, distal symmetrical motor neuropathy, and radiculopathy in the peripheral nervous system 3. Most subjects have had very mild peripheral neuropathy either by clinical or EMG criteria2. Nerve biopsy or autopsy has shown histopathological findings consistent with wallerian degeneration, axonal degeneration, demyelination, and vasculitis3. However, the pathogenic mechanisms of eosinophil in peripheral neuropathy are still unclear. Eosinophils contain cytotoxic granules that release eosinophil cationic protein, which is partially responsible for thromboembolism, neurotoxic protein, and major basic protein3.

It has been suggested that the neuropathy is progressive during the period of hypereosinophilia, but may show some clinical resolution after corticosteroid treatment2. The neurological symptoms, especially, neuropathies, take the longest to recover. The rare form of very severe neuropathy shows poor recovery4.

Cutaneous involvement occurs in more than 50% of patients with HES5. The most common lesions are erythematous pruritic papules and nodules, and angioedematous and urticarial lesions; the latter are associated with a better prognosis5. Other types of skin lesions are blistering lesions and vasculitic lesions that result from dermal microthrombi. Mucosal ulcerations, when they occur in HES, can cause significant morbidity and are difficult to treat5. Skin biopsy specimens usually show eosinophil-rich mixed cellular infiltrate6.

Table 1 summarizes the differential diagnoses of cutaneous disease with eosinophilia7. Sometimes HES shows clinical and electrophysiological features mimicking systemic vasculitis4. The systemic necrotizing vasculitis such as Churg-Strauss syndrome, periarteritis nodosa was excluded because none of the following manifestations were documented in our patient: fever, constitutional symptom, clear cut pulmonary affectations or asthma, sinusitis or rhinitis, and little response with corticosteroids. Also biopsy showed no vascular change in our case, and systemic necrotizing vasculitis was ruled out.

Glucocorticoids have been used as initial and maintenance therapy. For patients unresponsive to predinisone, hydroxyurea is added. Vincristine, INF-α, imatinib mesylate (Gleevec), and a tyrosine kinase inhibitor were found to be effective for certain patients with HES57. The aim is to maintain the leukocyte count at less than 10×109/L, with a normal eosinophil count8. Cardiac damage is the most important factor in the prognosis of HES. Improvement in peripheral eosinophilia correlates with an improved cardiac status7.

Recently two pathogenic variants of HES have been defined: myeloproliferative HES and lymphoproliferative HES5. Hematologic malignancy has been diagnosed in patients, 9~12 years after they were diagnosed with HES9. Though we could not perform a bone marrow evaluation to rule out hematologic malignancy, there was pure normal eosinophil infiltration in the skin biopsy specimens and no atypical eosinophil or eosinophilic precursor cell in the peripheral blood smear. From these findings, we could make a differential diagnosis of eosinophilic leukemia. With careful follow-up tests and a low-dose maintenance steroid therapy, the prognosis for our patients appears good.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

(A) Multiple, indurated plaques and crusted papules on both edematous legs. (B) Extensive eosinophil infiltration in the dermis (H&E, original magnification, ×200).

References

2. Werner RA, Wolf LL. Peripheral neuropathy associated with the hypereosinophilic syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990; 71:433–435.

3. Lee GH, Lee KW, Chi JG. Peripheral neuropathy as a hypereosinophilic syndrome and anti-GM1 antibodies. J Korean Med Sci. 1993; 8:225–229.

4. Prick JJ, Gabreels-Festen AA, Korten JJ, van der Wiel TW. Neurological manifestations of the hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES). Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1988; 90:269–273.

5. Leiferman KM, Gleich GJ. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: case presentation and update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004; 113:50–58.

6. Mcnutt NS, Moreno A, Contreras F. Inflammatory disease of the subcutaneous fat. In : Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL, Murphy GF, editors. Lever's histopathology of the skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2005. p. 525–526.

7. Leiferman KM, Peters MS, Gleich GJ. Eosinophils in cutaneous diseases. In : Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, editors. Dermatology in general medicine. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill;2003. p. 959–966.

8. Barna M, Kemeny L, Dobozy A. Skin lesions as the only manifestation of the hypereosinophilic syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1997; 136:646–647.

9. Stetson C. Eosinophilic dermatoses. In : Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, editors. Dermatology. 1st ed. London: Mosby;2003. p. 403–410.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download