Abstract

Although conventional prenatal screening tests for Down syndrome have been developed over the past 20 years, the positive predictive value of these tests is around 5%. Through these tests, many pregnant women have taken invasive tests including chorionic villi sampling and amniocentesis for confirming Down syndrome. Invasive test carries the risk of fetal loss at a low but significant rate. There is a large amount of evidence that non-invasive prenatal test (NIPT) using cell free DNA in maternal serum is more sensitive and specific than conventional maternal serum and/or ultrasound screening. Therefore implementing NIPT will increase aneuploidy detection rate and concurrently decrease fetal loss rate accompanying invasive test. More than 1,000,000 NIPT were performed globally since 2011. The uptake rate of NIPT is expected to increase more rapidly in the future. Moreover, as a molecular genetic technique advances, NIPT can be used for not only common aneuploidy screening but single gene disorder, microdeletion, and whole fetal genome sequencing. In this review, I will focus on the NIPT for common aneuploidies such as trisomy 13, 18, and 21.

다운증후군은 전세계적으로 약 1,000명 출생당 한 명 정도 태어나는 것으로 알려진 가장 흔한 염색체 이상으로 평생 동안 다양한 의료적 도움이 필요한 중요한 질병이다[1]. 1980년대부터 다운증후군에 대한 출생 전 선별검사는 많은 발전을 거듭해오고 있다. 산모의 나이, 초음파 소견(nuchal translucency), 모체 혈액의 단백질(pregnancy associated plasma protein-A, human chorionic gonadotropin 등) 등을 이용한 선별검사로 약 5%의 위양성율로 90%의 다운증후군을 선별해낼 수 있다[2]. 그러나 이런 선별검사의 가장 큰 문제는 검사의 양성예측도가 5% 정도로 낮기 때문에 너무 많은 융모막검사나 양수검사 같은 침습적인 산전검사가 행해지고, 이로 인해 태아가 유산될 수 있다는 것이다. 1997년 임산부 혈장에서 Y 염색체에서 유래한 cell free DNA (cfDNA)가 발견됨으로써[3] 산전진단은 새로운 전기를 마련하게 되었다. 태반에서 기원한 apoptotic trophoblasts로부터 유래된 cfDNA는 약 150 bp 크기의 잘려진 DNA 조각들이다[4]. 임신 4주 이후부터 발견되기 시작해서 10주 이후에는 평균 10% 정도가 태반에서 기원한 cfDNA이고 나머지 90%는 모체에서 유래한 cfDNA이다[5678]. 태반에서 기원한 cfDNA 양은 개인에 따라 다양할 수 있는데, 일반적으로 임신 주수가 증가할수록 증가하고, 모체의 체중이 증가할수록 감소한다[910]. 태반에서 기원한 cfDNA는 분만 2시간 이내 모체 혈장에서 발견되지 않기 때문에 산전진단의 좋은 재료가 될 수 있다[11]. Sequencing 기술과 bioinformatics의 발달로 검사 비용이 줄어듦에 따라 2011년부터 cfDNA를 이용한 다운증후군과 같은 흔한 염색체 이상에 대한 선별검사의 상업적 서비스가 중국과 미국에서 처음 시작되었다. 현재 cfDNA는 염색체 이상에 대한 선별검사뿐만 아니라 fetal whole genome sequencing [1213], fetal methylome sequencing [14], fetal transcriptome sequencing [15]에도 이용될 수 있게 되었다. 본 고찰에서는 지금 상업적으로 시행이 되고 있는 cfDNA를 이용한 다운증후군 같은 흔한 염색체 이상에 대한 비침습적 산전검사(non-invasive prenatal test, NIPT)에 초점을 맞추고자 한다.

현재 전 세계적으로 NIPT 서비스를 공급하고 있는 회사는 5개 정도이고, 국내외의 다른 회사들에서도 서비스를 준비 중이다. 각 회사별로 조금씩의 차이는 있지만 분석방법에 따라 크게 분류하면 counting method와 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping으로 분류할 수 있고, counting method는 모체 혈장의 모든 cfDNA를 sequencing 하는 shotgun massively parallel sequencing과 선별 대상이 되는 염색체 13, 18, 21, 성염색체에서 유래된 cfDNA만을 sequencing하는 targeted massively para-llel sequencing으로 분류할 수 있다(Figure 1).

모체 혈장에 존재하는 모든 cfDNA 조각을 증폭하여 sequencing을 한 후, 몇 번 염색체에서 유래된 DNA 조각인지를 분류하고(alignment), 그 개수를 counting한다. 다운증후군처럼 21번 염색체가 하나 더 있는 경우에 21번에서 유래된 DNA 조각이 상대적으로 조금 더 많을 것이기 때문에 이 차이를 이용하여 선별해낸다[1617]. 예를 들어 정상 태아를 임신한 것을 알고 있는 산모군의 혈장에서 21번 염색체에서 유래한 DNA 조각이 평균 1.5%를 차지하고 표준편차가 0.02인 경우, 검사한 샘플에서 21번 염색체에서 유래한 DNA 조각이 1.58%를 차지 한다면 Z-score=(1.58-1.5)/0.02=0.08/0.02=4이다. 일반적으로 Z-score가 3 이상인 경우 다운증후군 고위험군으로 분류 되므로 이 경우 다운증후군 고위험군으로 분류될 수 있다(Figure 2).

비용을 줄이고, 효율성을 높이기 위해 선별하고자 하는 염색체 13, 18, 21, X, Y에서 유래된 cfDNA 조각만을 선택적으로 증폭하여 sequencing한 후에 counting한다. 정상군과 비교하여 trisomy나 monosomy를 선별해낸다[18].

SNP는 인간집단에서 1% 이상의 빈도로 존재하는 단일 염기서열의 변이로 정의되며, 유전체 변이 중 가장 흔한 것으로 1억 4천만 개 이상이 밝혀져 있다(dbSNP build 144). 모체 혈액을 원심분리하면 혈장, buffy coat, 적혈구의 세 층으로 분리가 된다. 이중 buffy coat는 모체 백혈구들의 집합으로 이를 분석할 경우 모체만의 유전형을 알 수 있다. 혈장(모체 cfDNA + 태반 cfDNA)과 buffy coat에 대해서 약 20,000개의 SNP site를 multiplex polymerase chain reaction으로 증폭한 후 sequencing한다. SNP 유전형과 감수 분열 시의 교차 등을 고려하여 태아의 유전형을 추정하는데, 정상, trisomy, monosomy 중 가장 가능성이 높은 상태를 유추함으로써 선별해낸다(Figure 3) [2122].

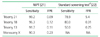

2008년 이후로 NIPT의 임상적 효용성에 대한 많은 연구가 있었다. 최근에 발표된 메타분석을 보면 기존의 모체 혈액검사와 초음파를 이용한 선별검사보다는 훨씬 뛰어난 성적을 보여준다 (Table 1) [2223]. 무엇보다 다운증후군에 대한 위양성율이 위양성율이 낮기 때문에 양수검사와 융모막검사 같은 침습적인 검사를 줄일 수 있다. 한 보고에 따르면 기존의 모체 혈액검사로 다운증후군 고위험군으로 선별된 경우 NIPT를 통해 2차적인 선별을 한다면 침습적인 검사가 90% 이상 줄어들고, 침습적인 검사에 따른 태아 유산도 90% 이상 감소할 것으로 기대된다[23].

실제 태아는 문제가 없지만 NIPT 결과는 문제가 있는 것으로 나오는 경우이다. 흔한 원인은 다음과 같다.

임신 초기 쌍태임신이었으나 한 명의 태아만 생존하는 경우로 일찍 산전 초음파가 시행되지 않는 경우, 알기 어려운 경우가 있다. 한 보고에 따르면 NIPT 검사에서 위양성이 나온 경우 약 15%는 vanishing twin 때문이다[26].

125,456건의 NIPT sample을 분석한 결과 3,757건에서 이상 소견이 발견 되었고, 이중 10건에서 숨겨진 산모의 암이 발견되었다. 이 중 7건에서는 두 가지 이상의 aneuploidy 소견이 동시에 관찰되었다[29]. 이런 경우 태아는 정상 염색체이나 NIPT 결과는 비정상으로 나올 수 있다.

NIPT를 실제 임상에 어떻게 적용할 것인가에 관한 많은 논란이 있다. 검사를 제공하는 회사들에서는 모든 산모들에게 검사를 제공하기를 원하고, 대부분의 전문가 단체에서는 고위험군(분만 시 산모의 나이가 35세 이상, 기존의 선별검사에서 고위험군으로 나온 경우, 부모의 염색체 이상으로 다운증후군이나 파타우증후군 고위험군인 경우, 이전에 다운증후군 같은 염색체 이상이 있었던 경우 등)에서만 NIPT를 고려할 것을 권고한다[43]. 현재 시행되고 있는 여러 가지 검사들 중에 어떤 것이 가장 뛰어난 검사인지에 관한 연구도 아직 없다.

기존의 혈액검사와 초음파검사로 고위험군으로 선별된 사람들에게 2차적 선별검사로 NIPT를 적용하는 모델이다. 다운증후군 발견율은 primary NIPT에 비해 떨어지지만 90% 이상의 침습적인 검사를 줄일 수 있고, 전체적인 비용 면에서도 유리하다.

Primary와 secondary의 중간단계의 모델로 기존의 선별검사에서 고위험군과, 중간위험군에 NIPT를 적용하는 모델이다. Primary NIPT에 비해 다운증후군의 발견율도 비슷하게 유지하면서 비용을 줄일 수 있는 장점이 있다. 국가적인 산전진단 프로그램을 운영하고 있는 영국 등에서는 가장 관심을 가지는 모델이다[46].

2011년 중국과 미국에서 이윤을 추구하는 기업의 주도로 NIPT가 상업적으로 제공됨에 따라 여러 전문가 단체에서 NIPT의 임상적 사용에 대한 가이드라인을 발표하였다[424347484951]. 거의 대부분의 가이드라인에서 현재 NIPT는 모든 산모를 대상으로 실행하지 말고 염색체 이상의 위험도가 높은 군에서 고려할 것을 권고 하고 있고, 무엇보다 NIPT를 환자에게 제공할 때는 검사 전후에 전문가에 의한 상세한 상담을 권고하였다.

NIPT는 다운증후군, 에드워드증후군, 파타우증후군, 터너증후군 같은 흔한 염색체 이상에 대한 선별검사로 기존의 선별검사보다 정확한 검사이지만 위양성과 위음성의 가능성이 있음을 설명해야 한다. 기존의 선별검사보다 고비용이 들고, 산전에 발견 되는 염색체 이상의 16.9-23.4%는 NIPT로 발견할 수 없다[3637]. NIPT는 신경관 결손증에 대한 AFP 검사와 nuchal translucency를 포함한 초음파 검사를 대신할 수는 없다. NIPT의 장점, 단점, 한계 등을 설명하고 환자로부터 informed consent를 받아야 한다.

고위험군으로 나온 경우 위양성의 가능성이 있으므로 반드시 융모막검사나 양수검사로 확인을 해야 한다. NIPT 결과만으로 돌이킬 수 없는 산과적인 결정을 하면 안 된다. NIPT의 양성예측도는 Table 2와 같다[42]. 예를 들어 25세의 여성이 NIPT 검사상 다운증후군 고위험군으로 나왔을 경우 태아가 진짜 다운증후군일 가능성은 33%이고 67%는 정상이라는 의미다. 나이와 임신 주수, 검사방법에 따른 검사결과의 양성 예측도를 간단히 인터넷으로 알려주는 사이트도 있다(http://mombaby.org/nips_calculator.html) [52].

저위험군으로 나온 경우에도 신경관결손증 검사와 초음파검사를 포함한 기존의 산전검진은 여전히 중요하고, 초음파검사에서 심장기형과 같은 이상 소견이 발견된 경우에는 NIPT가 저위험군이라고 하더라도 양수검사와 같은 침습적인 검사의 대상이 된다.

NIPT는 trisomy 13, 18, 21을 임신 10주라는 이른 시기부터 비교적 정확히 선별해내는 좋은 검사임에는 틀림이 없다. 현재 국내에서는 아직 제도적인 장치가 완전히 마련되지 않았고, 산부인과 학회나 유전의학회 등의 전문가단체에 의한 가이드라인도 없는 실정이다. 이윤을 추구하는 기업에 의해서 NIPT가 주도되고, 특허와 지적재산권에 대한 신청이 늘어나면서 검사의 가격이 올라가고 일반인의 접근성이 떨어질 수도 있다. 현재 환자에게 직접 검사가 시도되진 않지만, 광고를 통한 광범위한 마케팅으로 충분한 사전지식 없는 환자에게 검사가 행해질 수 있다. 적절한 규제 없이 시장경제 논리에만 맡겨질 경우 검사의 질에 심각한 문제를 초래할 수도 있다. 또한 윤리적 문제로는 NIPT로 인해 결국 낙태되는 염색체 이상 아이가 증가할 수도 있고, 치료하는 것에는 소홀하게 될 수 있다. 가장 큰 문제 중의 하나로 NIPT는 분명한 선별검사임에도 불구하고 NIPT 검사결과가 고위험군으로 나온 경우 6.2%에서는 융모막검사나 양수검사 같은 확진검사 없이 임신을 종결시킨 것으로 보고 되었다는 것이다[34]. 분자유전학기술의 발전으로 태아에 대한 너무 많은 정보를 출산 전에 알 수 있게 됨에 따라 부모를 불필요하게 불안하게 할 수도 있다. NIPT처럼 안전하고, 쉬운 검사일수록 informed consent를 통한 자발적인 선택이 잘 이루어지지 않을 수도 있다[53]. 예상되는 많은 문제점들을 해결하기 위해서는 전문가단체와 보건 당국에 의해 우리 나라에 가장 적합한 가이드라인을 만들어야 하고, 검사를 제공하는 의료인에 대한 교육도 시급한 과제이다.

NIPT는 기존의 다운증후군 선별검사보다 낮은 위양성율로 높은 발견율을 보이는 훌륭한 검사임에는 분명하다. 그렇지만 전술한 바와 같이 여러 가지 한계점을 가지고 있고, 고비용이 드는 검사이므로 현재로서는 고위험군 산모들을 대상으로 우선적으로 시행하고, 검사 전후에 담당 선생님에 의한 적절한 유전상담이 매우 중요하다. 또한 NIPT 검사 결과가 고위험군으로 나온 경우, 이 결과만으로 돌이킬 수 없는 산과적인 결정을 하지 말고, 반드시 융모막검사나 양수검사로 확인검사를 해야 한다.

태아 염색체 이상을 진단하는데 있어 가장 정확한 방법은 융모막 검사 및 양수검사 등의 침습적인 검사이지만 비용과 태아손실 위험성으로 보편화할 수는 없다. 이에 따라 비침습적이면서 낮은 위양성율, 높은 발견율을 보일 수 있는 다양한 모체 혈청 선별검사 방법이 개발되었으며 현재도 진화하고 있다. 본 논문에서는 최근 들어 각광받고 있는 모체혈장내 유리 DNA를 이용한 선별검사법을 소개하고 있고 그 원리를 이해하기 쉽게 설명하고 있으며, 기존의 검사법보다 우수한 점을 나열하고 있다. 그러나 마치 이 검사법이 양수검사 등의 침습적인 검사를 대체할 수 있는 것처럼 알려지는 것을 경계하고 있고, 정확성, 안전성, 경제성을 고려하여 산모 및 보호자와 충분히 상의하여 결정하는 것이 의료진의 중요한 역할이라고 강조하고 있다.

[정리: 편집위원회]

Figures and Tables

Figure 1

Classification of non-invasive prenatal test (NIPT). cfDNA, cell free DNA; S-MPS, shotgun massively parallel sequencing; T-MPS, targeted massively parallel sequencing; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; BGI, Beijing Genomics institute.

Figure 2

Principle of single nucleotide polymorphism method. SD, standard deviation; cfDNA, cell free DNA.

Figure 3

Simplified principle of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) based non-invasive prenatal test. Each dot is one SNP and is the sum of both the maternal and fetal contribution. SNPs are biallelic and thus have only 1 of 2 DNA bases possible (which we reference as A and B). The SNPs are only 1 per location going left to right (like the chromosome was lying on its side), total about 3,000 SNPs per chromosome (you could see this if it were spread out more). Top of profile is 100% A 0% B. Continuing to go down the profile, A decreases and B increases until the bottom is 100% B and 0% A. RED SNPs are where mom is AA. The top line is where baby is also AA (thus 100% A). The second has 75% A and 25% B (baby AB). Green SNPs are where mom is AB. Again increasing B% from the 1st to third line. Blue SNPs are where mom is BB. Again increasing B% until the final line where baby and mom are 100% B. When the mother's SNP is heterozygous (Green SNP), an extra band appears when the fetus is trisomic. However, the band positions are dependent on allele frequency and fetal fraction. When the mother's SNP is homozygous (red and Blue SNP), one band is shifted when the fetus is trisomic. Amount of shift is dependent on allele frequency and fetal fraction. Not all SNP profile results are visually conclusive and thus why the algorithm is needed [20].

References

1. Weijerman ME, de Winter JP. Clinical practice: the care of children with Down syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 2010; 169:1445–1452.

3. Lo YM, Corbetta N, Chamberlain PF, Rai V, Sargent IL, Redman CW, Wainscoat JS. Presence of fetal DNA in maternal plasma and serum. Lancet. 1997; 350:485–487.

4. Chan KC, Zhang J, Hui AB, Wong N, Lau TK, Leung TN, Lo KW, Huang DW, Lo YM. Size distributions of maternal and fetal DNA in maternal plasma. Clin Chem. 2004; 50:88–92.

5. Lun FM, Chiu RW, Chan KC, Leung TY, Lau TK, Lo YM. Microfluidics digital PCR reveals a higher than expected fraction of fetal DNA in maternal plasma. Clin Chem. 2008; 54:1664–1672.

6. Fan HC, Blumenfeld YJ, Chitkara U, Hudgins L, Quake SR. Analysis of the size distributions of fetal and maternal cell-free DNA by paired-end sequencing. Clin Chem. 2010; 56:1279–1286.

7. Nygren AO, Dean J, Jensen TJ, Kruse S, Kwong W, van den Boom D, Ehrich M. Quantification of fetal DNA by use of methylation-based DNA discrimination. Clin Chem. 2010; 56:1627–1635.

8. Sikora A, Zimmermann BG, Rusterholz C, Birri D, Kolla V, Lapaire O, Hoesli I, Kiefer V, Jackson L, Hahn S. Detection of increased amounts of cell-free fetal DNA with short PCR amplicons. Clin Chem. 2010; 56:136–138.

9. Nicolaides KH, Syngelaki A, Ashoor G, Birdir C, Touzet G. Noninvasive prenatal testing for fetal trisomies in a routinely screened first-trimester population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012; 207:374.e1–374.e6.

10. Ashoor G, Poon L, Syngelaki A, Mosimann B, Nicolaides KH. Fetal fraction in maternal plasma cell-free DNA at 11-13 weeks' gestation: effect of maternal and fetal factors. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2012; 31:237–243.

11. Lo YM, Zhang J, Leung TN, Lau TK, Chang AM, Hjelm NM. Rapid clearance of fetal DNA from maternal plasma. Am J Hum Genet. 1999; 64:218–224.

12. Kitzman JO, Snyder MW, Ventura M, Lewis AP, Qiu R, Simmons LE, Gammill HS, Rubens CE, Santillan DA, Murray JC, Tabor HK, Bamshad MJ, Eichler EE, Shendure J. Noninvasive whole-genome sequencing of a human fetus. Sci Transl Med. 2012; 4:137ra76.

13. Fan HC, Gu W, Wang J, Blumenfeld YJ, El-Sayed YY, Quake SR. Non-invasive prenatal measurement of the fetal genome. Nature. 2012; 487:320–324.

14. Lun FM, Chiu RW, Sun K, Leung TY, Jiang P, Chan KC, Sun H, Lo YM. Noninvasive prenatal methylomic analysis by genomewide bisulfite sequencing of maternal plasma DNA. Clin Chem. 2013; 59:1583–1594.

15. Tsui NB, Jiang P, Wong YF, Leung TY, Chan KC, Chiu RW, Sun H, Lo YM. Maternal plasma RNA sequencing for genome-wide transcriptomic profiling and identification of pregnancy-associated transcripts. Clin Chem. 2014; 60:954–962.

16. Chiu RW, Chan KC, Gao Y, Lau VY, Zheng W, Leung TY, Foo CH, Xie B, Tsui NB, Lun FM, Zee BC, Lau TK, Cantor CR, Lo YM. Noninvasive prenatal diagnosis of fetal chromosomal aneuploidy by massively parallel genomic sequencing of DNA in maternal plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008; 105:20458–20463.

17. Fan HC, Blumenfeld YJ, Chitkara U, Hudgins L, Quake SR. Noninvasive diagnosis of fetal aneuploidy by shotgun sequencing DNA from maternal blood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008; 105:16266–16271.

18. Sparks AB, Wang ET, Struble CA, Barrett W, Stokowski R, McBride C, Zahn J, Lee K, Shen N, Doshi J, Sun M, Garrison J, Sandler J, Hollemon D, Pattee P, Tomita-Mitchell A, Mitchell M, Stuelpnagel J, Song K, Oliphant A. Selective analysis of cell-free DNA in maternal blood for evaluation of fetal trisomy. Prenat Diagn. 2012; 32:3–9.

19. Zimmermann B, Hill M, Gemelos G, Demko Z, Banjevic M, Baner J, Ryan A, Sigurjonsson S, Chopra N, Dodd M, Levy B, Rabinowitz M. Noninvasive prenatal aneuploidy testing of chromosomes 13, 18, 21, X, and Y, using targeted sequencing of polymorphic loci. Prenat Diagn. 2012; 32:1233–1241.

20. Hall MP, Hill M, Zimmermann B, Sigurjonsson S, Westemeyer M, Saucier J, Demko Z, Rabinowitz M. Non-invasive prenatal detection of trisomy 13 using a single nucleotide polymorphism- and informatics-based approach. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e96677.

21. Gil MM, Quezada MS, Revello R, Akolekar R, Nicolaides KH. Analysis of cell-free DNA in maternal blood in screening for fetal aneuploidies: updated meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 45:249–266.

22. Norton ME, Jacobsson B, Swamy GK, Laurent LC, Ranzini AC, Brar H, Tomlinson MW, Pereira L, Spitz JL, Hollemon D, Cuckle H, Musci TJ, Wapner RJ. Cell-free DNA analysis for noninvasive examination of trisomy. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:1589–1597.

23. Palomaki GE, Deciu C, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, Haddow JE, Neveux LM, Ehrich M, van den Boom D, Bombard AT, Grody WW, Nelson SF, Canick JA. DNA sequencing of maternal plasma reliably identifies trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 as well as Down syndrome: an international collaborative study. Genet Med. 2012; 14:296–305.

25. Choi H, Lau TK, Jiang FM, Chan MK, Zhang HY, Lo PS, Chen F, Zhang L, Wang W. Fetal aneuploidy screening by maternal plasma DNA sequencing: 'false positive' due to confined placental mosaicism. Prenat Diagn. 2013; 33:198–200.

26. Futch T, Spinosa J, Bhatt S, de Feo E, Rava RP, Sehnert AJ. Initial clinical laboratory experience in noninvasive prenatal testing for fetal aneuploidy from maternal plasma DNA samples. Prenat Diagn. 2013; 33:569–574.

27. Russell LM, Strike P, Browne CE, Jacobs PA. X chromosome loss and ageing. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2007; 116:181–185.

28. Wang Y, Chen Y, Tian F, Zhang J, Song Z, Wu Y, Han X, Hu W, Ma D, Cram D, Cheng W. Maternal mosaicism is a significant contributor to discordant sex chromosomal aneuploidies associated with noninvasive prenatal testing. Clin Chem. 2014; 60:251–259.

29. Bianchi DW, Chudova D, Sehnert AJ, Bhatt S, Murray K, Prosen TL, Garber JE, Wilkins-Haug L, Vora NL, Warsof S, Goldberg J, Ziainia T, Halks-Miller M. Noninvasive prenatal testing and incidental detection of occult maternal malignancies. JAMA. 2015; 314:162–169.

30. Snyder MW, Simmons LE, Kitzman JO, Coe BP, Henson JM, Daza RM, Eichler EE, Shendure J, Gammill HS. Copy-number variation and false positive prenatal aneuploidy screening results. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:1639–1645.

31. Smith M, Lewis KM, Holmes A, Visootsak J. A case of false negative NIPT for Down syndrome-lessons learned. Case Rep Genet. 2014; 2014:823504.

32. Canick JA, Palomaki GE, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, Haddow JE. The impact of maternal plasma DNA fetal fraction on next generation sequencing tests for common fetal aneuploidies. Prenat Diagn. 2013; 33:667–674.

33. Palomaki GE, Kloza EM, Lambert-Messerlian GM, van den Boom D, Ehrich M, Deciu C, Bombard AT, Haddow JE. Circulating cell free DNA testing: are some test failures informative? Prenat Diagn. 2015; 35:289–293.

34. Dar P, Curnow KJ, Gross SJ, Hall MP, Stosic M, Demko Z, Zimmermann B, Hill M, Sigurjonsson S, Ryan A, Banjevic M, Kolacki PL, Koch SW, Strom CM, Rabinowitz M, Benn P. Clinical experience and follow-up with large scale single-nucleotide polymorphism-based noninvasive prenatal aneuploidy testing. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014; 211:527.e1.

35. Wegrzyn P, Faro C, Falcon O, Peralta CF, Nicolaides KH. Placental volume measured by three-dimensional ultrasound at 11 to 13+6 weeks of gestation: relation to chromosomal defects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 26:28–32.

36. Norton ME, Jelliffe-Pawlowski LL, Currier RJ. Chromosome abnormalities detected by current prenatal screening and noninvasive prenatal testing. Obstet Gynecol. 2014; 124:979–986.

37. Petersen OB, Vogel I, Ekelund C, Hyett J, Tabor A. Danish Fetal Medicine Study Group. Danish Clinical Genetics Study Group. Potential diagnostic consequences of applying non-invasive prenatal testing: population-based study from a country with existing first-trimester screening. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014; 43:265–271.

38. Leung TY, Qu JZ, Liao GJ, Jiang P, Cheng YK, Chan KC, Chiu RW, Lo YM. Noninvasive twin zygosity assessment and aneuploidy detection by maternal plasma DNA sequencing. Prenat Diagn. 2013; 33:675–681.

39. Lau TK, Jiang F, Chan MK, Zhang H, Lo PS, Wang W. Noninvasive prenatal screening of fetal Down syndrome by maternal plasma DNA sequencing in twin pregnancies. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013; 26:434–437.

40. Huang X, Zheng J, Chen M, Zhao Y, Zhang C, Liu L, Xie W, Shi S, Wei Y, Lei D, Xu C, Wu Q, Guo X, Shi X, Zhou Y, Liu Q, Gao Y, Jiang F, Zhang H, Su F, Ge H, Li X, Pan X, Chen S, Chen F, Fang Q, Jiang H, Lau TK, Wang W. Noninvasive prenatal testing of trisomies 21 and 18 by massively parallel sequencing of maternal plasma DNA in twin pregnancies. Prenat Diagn. 2014; 34:335–340.

41. del Mar Gil M, Quezada MS, Bregant B, Syngelaki A, Nicolaides KH. Cell-free DNA analysis for trisomy risk assessment in first-trimester twin pregnancies. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2014; 35:204–211.

42. Committee Opinion No. 640: cell-free DNA screening for fetal aneuploidy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 126:e31–e37.

43. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Genetics. Committee Opinion No. 545: noninvasive prenatal testing for fetal aneuploidy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012; 120:1532–1534.

44. Cuckle H, Benn P, Pergament E. Cell-free DNA screening for fetal aneuploidy as a clinical service. Clin Biochem. 2015; 48:932–941.

45. Benn P, Borrell A, Chiu RW, Cuckle H, Dugoff L, Faas B, Gross S, Huang T, Johnson J, Maymon R, Norton M, Odibo A, Schielen P, Spencer K, Wright D, Yaron Y. Position statement from the Chromosome Abnormality Screening Committee on behalf of the Board of the International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis. Prenat Diagn. 2015; 35:725–734.

46. Hill M, Wright D, Daley R, Lewis C, McKay F, Mason S, Lench N, Howarth A, Boustred C, Lo K, Plagnol V, Spencer K, Fisher J, Kroese M, Morris S, Chitty LS. Evaluation of non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) for aneuploidy in an NHS setting: a reliable accurate prenatal non-invasive diagnosis (RAPID) protocol. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014; 14:229.

47. Langlois S, Brock JA. Genetics Committee. Wilson RD, Audibert F, Brock JA, Carroll J, Cartier L, Gagnon A, Johnson JA, Langlois S, Macdonald W, Murphy-Kaulbeck L, Okun N, Pastuck M, Senikas V. Current status in non-invasive prenatal detection of Down syndrome, trisomy 18, and trisomy 13 using cell-free DNA in maternal plasma. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2013; 35:177–183.

48. Dondorp W, de Wert G, Bombard Y, Bianchi DW, Bergmann C, Borry P, Chitty LS, Fellmann F, Forzano F, Hall A, Henneman L, Howard HC, Lucassen A, Ormond K, Peterlin B, Radojkovic D, Rogowski W, Soller M, Tibben A, Tranebjærg L, van El CG, Cornel MC. Non-invasive prenatal testing for aneuploidy and beyond: challenges of responsible innovation in prenatal screening. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015; 23:1438–1450.

49. Wilson KL, Czerwinski JL, Hoskovec JM, Noblin SJ, Sullivan CM, Harbison A, Campion MW, Devary K, Devers P, Singletary CN. NSGC practice guideline: prenatal screening and diagnostic testing options for chromosome aneuploidy. J Genet Couns. 2013; 22:4–15.

50. Salomon LJ, Alfirevic Z, Bilardo CM, Chalouhi GE, Ghi T, Kagan KO, Lau TK, Papageorghiou AT, Raine-Fenning NJ, Stirnemann J, Suresh S, Tabor A, Timor-Tritsch IE, Toi A, Yeo G. ISUOG practice guidelines: performance of first-trimester fetal ultrasound scan. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 41:102–113.

51. Gregg AR, Gross SJ, Best RG, Monaghan KG, Bajaj K, Skotko BG, Thompson BH, Watson MS. ACMG statement on noninvasive prenatal screening for fetal aneuploidy. Genet Med. 2013; 15:395–398.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download