Abstract

Sudden cardiac arrest is a growing medical issue in developed countries. Annually, more than 25,000 out-of-hospital cardiac arrests (OHCA) occur in Korea. Only 3% of victims with OHCA discharge alive from hospital and less than 1% of them survive neurologically intact. Major changes of recent guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and emergency cardiac care includes modification of basic life support (BLS) sequence from A-B-C to C-A-B, an emphasis on minimally interrupted, high-quality chest compression, the introduction of chest compression-only CPR, and addition of integrated post-cardiac arrest care concept as the fifth chain in the Chain of Survival. Repetition of 2-minutes of CPR, rhythm check, and defibrillation if indicated is recommended as a universal algorithm during BLS. Defibrillation and drug administration including epinephrine should not be delayed to place an advanced airway during CPR. Important interventions during post-cardiac arrest care are comprised of the optimization of ventilation (arterial CO2 tension, 40 to 45 mmHg) and oxygenation (arterial O2 saturation, 94% to 98%), glucose control (blood glucose, 144 to 180 mg/dL), therapeutic hypothermia (body tem-perature, 32℃ to 34℃) for unresponsive patients, and percutaneous coronary intervention for the patient with ST-segment elevation. Systemic approaches to increase public awareness of cardiac arrest and CPR, to spread CPR education to citizen, and to implement public access defibrillation are a prerequisite for improving survival from OHCA in the community. Effective advanced life support and integrated post-cardiac arrest care should be provided to increase neurologically intact survival among the patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest.

심장정지(cardiac arrest)는 갑작스런 순환정지로 인하여 예측되지 않은 사망을 초래하는 치명적 증후군이며, 보건의료선진국의 주요 보건문제로 대두되고 있다. 심장정지(out-of-hospital cardiac arrest)의 발생 확률은 부정맥, 관상동맥질환, 심부전 등 주요 심장질환을 가진 고위험군에서 높지만, 발생 숫자는 아무 임상증상이 없는 일반인이나 심혈관질환의 통상 위험군에서 더 많다[1]. 질병구조의 서구화에 따라 우리나라의 심장정지 환자 발생빈도는 증가 추세에 있다. 심장정지의 발생빈도는 2006년의 10만 명당 37.5명에서 2010년의 10만 명당 46.8명으로 증가하였으며, 2010년도 우리나라의 병원 밖 심장정지 발생 수은 연간 25,000명 정도이다[2]. 심장정지의 생존율은 각 지역사회 응급의료 수준의 지표 역할을 하고 있다. 우리나라의 심장정지 생존율은 3% 내외로서 의료 선진국의 7-12%에 비하여 낮다[345].

심폐소생술(cardiopulmonary resuscitation)은 심장정지 환자에게 가슴압박(chest compression)과 구조호흡(rescue breathing)을 제공하는 기본소생술(basic life support)과 약물투여, 제세동(defibrillation), 심장정지 후 통합치료로서 환자를 소생시키기 위한 전문소생술로 구성된다. 심장정지 환자의 생존율을 높이려면 효과적인 기본 및 전문소생술이 시행되어야 할 뿐 아니라, 일반인에 대한 심폐소생술 교육의 확대, 자동제세동기의 광범위한 보급, 현장 및 이송 응급치료체계 효율화, 심장정지후증후군(post-cardiac arrest syndrome)에 대한 전문치료가 수행되어야 한다. 이 논문에서는 심폐소생술의 최신 가이드라인과 경향을 소개한다.

심장정지는 주로 가정, 공공장소, 운동시설 등 병원 이외의 장소에서 발생하기 때문에 심장정지 발생 현장에 함께 있는 일반인의 구조활동과 응급의료체계의 현장 및 이송 중 응급처치, 병원 내 전문치료의 적절성이 심장정지 생존율에 영향을 준다. 생존사슬(chain of survival)은 심장정지 환자를 소생시키기 위한 필수적인 요소가 사슬처럼 연속적으로 이어져 있어야 한다는 개념이다. 생존사슬은 심장정지가 발생한 현장에서의 빠른 신고(immediate recognition and activation), 목격자에 의한 현장 심폐소생술(early cardio-pulmonary resuscitation), 심실세동에 대한 신속한 제세동(rapid defibrillation)과 전문의료진의 효율적인 전문소생술(effective advanced life support), 심장정지 후 통합치료(integrated post-cardiac arrest care)로 구성되어 있다[6].

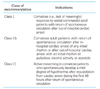

1966년 American Academy of Science가 첫 심폐소생술 가이드라인을 제정한 이후, 미국과 유럽은 각 국가별 심폐소생술 가이드라인을 발표하고 있다[7]. 2000년 이후로는 심폐소생술국제연락위원회(International Liaison Com-mittee on Resuscitation, ILCOR)가 중심이 되어 5년마다 국제 가이드라인을 발표하고 있으며 가장 최근의 가이드라인은 2010년에 발표되었다[8]. 우리나라에서는 보건복지부 사업으로 대한심폐소생협회가 2006년에 첫 가이드라인을 발표하였으며, 2011년에 개정 가이드라인을 발표하였다. 최근 발표된 심폐소생술 가이드라인의 주요 개정 내용은 기본소생술 순서의 변경, 심장정지 확인 및 심폐소생술 과정의 단순화, 가슴압박 방법의 조정 및 가슴압박소생술 도입, 심장정지 후 통합치료 개념의 도입이다(Table 1) [6]. 특히, 심폐소생술 후 자발순환이 회복되더라도 성인 환자의 67%, 소아 환자의 55%가 심장정지후증후군 또는 순환부전으로 사망하기 때문에 소생 후 초기 집중치료를 강조한 심장정지 후 통합치료 개념은 새로운 가이드라인의 핵심 내용이다[9]. 심폐소생술 가이드라인에서 변경된 주요 내용을 2010년 ILCOR의 권장사항을 중심으로 요약하였다.

이전의 가이드라인에서는 심장정지를 확인하는 과정으로서 각각 10초간 호흡과 맥박을 확인하도록 하였다. 그러나 이 과정은 심폐소생술 시작을 지연시킬 뿐 아니라, 실제 심장정지를 확인하는 방법으로서의 효용성이 낮다. 개정된 가이드라인에서는 의식이 없고 호흡과 움직임이 없는 환자는 심장정지로 판단하도록 함으로써 호흡 및 맥박 확인 과정을 생략하여 단순화하였다. 따라서 심장정지가 의심되는 사람을 발견한 사람은 반응을 확인하고(determine unresponsiveness) 호흡이 없거나 비정상 호흡이 관찰되면 즉시 119에 구조요청을 한 후 가슴압박을 시작하도록 권장하고 있다. 다만, 의료인 구조자는 심장정지를 진단하기 위하여 10초 이내로 목동맥박을 확인한다.

심폐소생술에서 가슴압박의 중요성이 강조되면서 기존의 기도유지-인공호흡-가슴압박(airway-breathing-circulation, A-B-C) 순서는 C-A-B로 바뀌었다. 즉, 심장정지가 확인되면 즉시 30회의 가슴압박 후 2회의 인공호흡 과정을 반복한다. C-A-B 순서의 기본소생술은 A-B-C 순서보다 구조자가 가슴압박을 시작할 때까지의 시간을 단축한다[10].

성인 심장정지 환자에게 심폐소생술을 할 경우에 5 cm의 가슴압박 깊이, 분당 100회의 압박 속도를 권장한 이전의 가이드라인에 따라 실제 심폐소생술을 한 결과, 압박 깊이가 38 mm 미만이었던 경우가 37.4%, 압박속도가 분당 80회 미만인 경우가 36.9%로 압박 깊이와 속도가 가이드라인에 부합되지 않은 경우가 많았다[1112]. 이에 따라 개정된 가이드라인에서는 성인에서 최소 5 cm(최대 6 cm)의 압박 깊이와 분당 최소 100회 이상(최대 120회 이하)의 압박속도를 권장하였으며, 가슴압박 중단을 최소화하고, 압박 이완기에는 압박된 가슴을 완전히 이완시키도록 권장하였다.

심장정지 발생 초기에는 수 분 동안 혈액 내에 산소가 잔존되어 있다가 심장정지가 지속되거나 심폐소생술이 진행되면 혈액 내 산소량이 급격히 감소한다[13]. 따라서 순환이 갑자기 중단된 심장정지 발생 초기에는 혈액 내 잔존 산소가 있기 때문에 구조호흡이 반드시 필요하지는 않다. 최근 일련의 임상연구에 따르면 심장정지 환자에게 구조호흡은 하지 않고 가슴압박만을 하는 가슴압박소생술을 한 경우와 구조호흡과 가슴압박을 모두 한 경우에 생존율의 차이가 없거나 오히려 가슴압박소생술을 한 경우에 생존율이 높다고 보고되었다[31415]. 이를 근거로 일반인 구조자 중 구조호흡을 꺼리거나 구조호흡을 능숙히 하지 못하는 사람은 가슴압박소생술을 하도록 권장하고있다.

전문소생술 과정은 기본소생술 과정을 수행하면서 약물투여를 위한 정맥로 또는 골내(intraosseous) 주사로의 확보 및 약물투여, 기관내삽관 등 전문기도유지(advance airway placement), 심전도 리듬 분석 결과에 따라 제세동을 수행하는 과정이다. 전문소생술 동안에는 가슴압박과 인공호흡을 2분간 시행한 후 심전도 분석 결과에 따라 심실세동(ventricular fibrillation) 또는 무맥박심실빈맥(pulseless ventricular tachycardia) 등 제세동이 필요한 리듬(shockable rhythm)이 관찰되면 제세동을 하고, 심장무수축(asystole) 또는 무맥박전기활성(pulseless electrical activities) 등 제세동이 필요하지 않은 리듬(nonshockable rhythm)이 관찰되면 심폐소생술을 계속한다. 심장정지 상태가 계속되면 2분 심폐소생술, 리듬 분석, 제세동 과정을 반복한다(Figure 1).

전문기도유지를 하기 위하여 가슴압박과 제세동이 지연되어서는 안된다. 심폐소생술 초기에는 입대입 인공호흡(mouth-to-mouth ventilation) 또는 백-마스크 인공호흡(bag-mask ventilation)으로 환자에게 충분한 산소를 공급할 수 있다. 심장정지 발생 후 전문기도유지를 해야 하는 시기에 대해서는 잘 알려져 있지 않다. 병원 밖 심장정지환자에서의 조사에 따르면, 심폐소생술 동안 기관내삽관 등 전문기도유지를 한 경우가 백-밸브-마스크 인공호흡을 한 경우보다 생존율이 낮았다(odds ratio, 0.38)고 알려졌다[16]. 반면, 병원 내 심장정지 환자를 대상으로 조사한 결과에서는 5분 이내에 전문기도유지를 한 경우에 순환회복률은 증가하지 않았으나 24시간 생존율을 증가시켰다는 보고가 있다[17]. 따라서 현재로서는 제세동, 약물투여로 확보가 시행된 후에도 심장정지가 계속되는 경우에 기관내튜브 또는 후두마스크기도기(laryngeal mask airway)를 사용한 전문기도유지를 권장한다. 전문기도유지가 된 후에는 인공호흡을 위하여 가슴압박을 중단할 필요가 없다.

심폐소생술 중에는 관류압(perfusion pressure)을 유지하기 위하여 혈압상승제(vasopressor)를 투여한다. 혈압상승제로는 에피네프린(epinephrine) 1.0 mg(성인 기준)을 3-5분 간격으로 반복투여하며, 에피네프린의 첫 번째 또는 두 번째 투여를 대신하여 바소프레신(vasopressin) 40 IU을 투여할 수 있다. 에피네프린의 투여는 순환회복률을 증가시키지만, 베타교감신경작용으로 심근손상을 유발하고 뇌혈류량을 감소시킴으로써 심장정지 후 24시간 생존율을 감소시키는 것으로 알려졌다[18]. 에피네프린을 대신하는 방법으로서 바소프레신 투여, 에피네프린-바소프레신 병합투여의 임상시험이 진행되었으나, 에피네프린 단독투여와 비교하여 생존율의 차이가 나타나지 않았다[1920]. 반면, 에피네프린과 함께 심장무수축과 무맥박전기활동의 치료에 사용되던 아트로핀(atropine)은 투여하더라도 30일 생존율에 영향을 주지 못하는 것으로 조사되어 더 이상 사용이 권장되지 않는다[21]. Shockable rhythm의 치료과정에서 제세동에 실패하면 amiodarone(첫 용량 300 mg, 두 번째 용량 150 mg)을 투여한다. Amiodarone을 사용할 수 없는 경우에는 리도카인(lidocaine)을 투여한다.

심장정지 후 통합치료는 개정 가이드라인에서 가장 강조되고 있는 분야이다. 심장정지로부터 소생되면 전신적으로 심각한 허혈-재관류 손상이 발생하여 뇌 등의 장기부전이 초래되는 심장정지후증후군이 발생한다. 심장정지후증후군은 허혈뇌병(ischemic encephalopathy), 기절심근(myocardial stunning) 현상, 전신성 허혈/재관류 반응(systemic ischemia/reperfusion response)에 의한 혈역학적/대사성 변화로 나타나는 복합현상이다[22]. 심장정지 후 치료의 주요 목적은 심장정지후증후군의 발생을 최소화하고 적극적으로 치료하는 것으로서, 심장정지 후 치료에는 신속한 혈역학적 안정화, 폐 환기 조절, 신경학적 손상을 최소화하기 위한 체온조절, 다발성장기부전의 치료, 급성관상동맥증후군의 조기발견 및 치료가 포함된다[23]. 소생 직후에는 혈역학적 안정화를 위하여 평균 동맥압을 65 mmHg 이상 유지하여야 하며, 폐 환기는 동맥혈 이산화탄소압을 40-45 mmHg(호기말 이산화탄소압 35-40 mmHg)로 유지한다. 동맥혈 산소포화도는 94-98%를 유지하고, 혈당은 144-180 mg/dL 범위 내에서 조절하되 저혈당이 발생하지 않도록 한다. 또한 심장정지의 주요원인인 급성관상동맥증후군의 발생여부를 확인하여 적극적인 중재술을 시도한다. 소생 직후 기록한 심전도에서 ST절 상승이 관찰된 환자에서 의식이 없더라도 경피관상동맥중재술(percutaneous coronary intervention)을 시행한 경우의 44%가 생존하였고 생존 환자의 88%가 신경학적으로 완전히 회복되었다고 보고되었다[24]. 따라서 소생 후의 심전도 상 ST절 상승이 관찰되면 환자의 의식 유무에 관계없이 즉시 경피관상동맥중재술을 한다[25].

심실세동에 의한 심장정지로부터 소생된 직후 의식이 없는 환자에게 각각 12시간 또는 24시간 동안 저체온치료(therapeutic hypothermia)를 한 결과, 저체온치료를 하지 않은 군에 비하여 생존율이 높고 신경학적으로 양호한 예후가 관찰되었다[2627]. 이를 근거로 심장정지 시의 심전도 상 심실세동 또는 무맥박심실빈맥이 관찰되었고, 소생 후 혈역학적으로 안정적이지만 무의식 상태(Glasgow Coma Scale 8점 미만)인 환자에게는 소생 후 12-24시간 동안 체온을 32-34℃로 유지하는 저체온치료가 권장된다[28]. 심실세동에 의한 심장정지 환자와 동등한 신경학적 회복 효과는 분명하지 않으나, 심실세동 이외의 심전도 리듬(심장무수축 또는 무맥박 전기 활성)에 의한 심장정지 환자에게도 저체온치료를 한다(Table 2) [2329]. 저체온치료를 얼마나 빨리 시작하여야 하는가에 대한 연구에서 순환회복 후 2시간 이내에 저체온치료를 시작한 환자군의 사망률이 2시간 이후에 저체온치료를 시작한 경우보다 사망률이 높았다고 보고되었다[30]. 즉, 저체온요법의 시작 시점이 예후와 연관이 있다는 증거는 없으며, 저체온치료를 지속하여야 하는 시간에 대한 임상연구도 부족하다. 따라서 진료현장에서는 순환회복 후 응급실이나 중환자실에서 가능한 빨리 저체온치료를 시작하여야 하며, 경피관상동맥 중재가 시행될 때에도 저체온치료를 함께 시작하여야 한다. 저체온을 유도하려면 0-4℃의 생리식염수를 체중 1 kg당 30 mL의 양으로 투여한 후 다양한 방법으로 저체온을 유지한다. External cooling에는 cooling blankets, fluid pads 또는 ice pack이 사용되며, 비강에 찬 가스를 순환시키는 nasopharyngeal cooling방법도 사용된다[31]. Internal cooling방법은 혈관(하대정맥) 내에 cooling catheter를 넣은 후 cold fluid를 순환시키는 방법(endovascular cooling)이 사용된다. 저체온치료를 끝내고 재가온할 때에는 체온을 0.25-0.5℃/hr의 속도로 정상으로 회복시킨다. 저체온치료 중 체온감시에 적절한 신체 부위로서 폐동맥 도자가 삽관되어 있는 경우에는 폐동맥이 가장 유용하나 침습적 방법이라는 제한이 있기 때문에 통상 식도 또는 방광이 권장된다[32]. 저체온치료 중 발생하는 오한은 근육이완제 또는 진정제를 사용하여 억제한다. 저체온치료는 부정맥, 저혈압, 출혈, 패혈증, 전해질 이상을 유발할 수 있으며 폐렴과 경련의 빈도를 증가시키나, 통상적 경도의 저체온치료가 심각한 합병증을 유발하지는 않는다[262728].

심장정지 환자에게 가슴압박으로 인공순환을 유지할 때 유발되는 심박출량은 정상 상태의 1/3 내외에 불과하기 때문에 인공순환을 대체하거나 순환혈류량을 높이기 위한 방법이 시도되어 임상적으로 적용되고 있다. 가슴압박을 기계적으로 대체한 자동가슴압박장치(automatic chest com-pression device), 가슴을 둘러싸는 밴드를 수축시켜 혈류를 유발하는 load-distributing band device, 가슴에 흡착되는 컵 모양의 기구를 사용하여 가슴압박과 이완을 반복하도록 고안된 automatic active compression-decompression device, 압박 이완기에 기도를 통한 흡기를 차단하여 정맥혈 환류량을 증가시키는 impedance threshold device가 임상적으로 시도되고 있다. Load-distributing band device 또는 automatic active compression-decompression device를 사용한 일부 임상시험에서 대체방법에 의한 심폐소생술이 표준 심폐소생술에 비하여 생존율 측면에서 우수하다고 보고되었다[3334]. 그러나 새로운 심폐소생술 방법은 기계 또는 기구를 사용해야 하며 생존율 개선 효과가 뚜렷하지 않기 때문에 현재의 표준 심폐소생술을 대체하지는 못하고 있다.

심폐소생술 중 인공순환 방법으로서 체외순환보조소생술(extracorporeal life support)에 대한 관심이 높아지고 있다. 체외순환보조소생술은 병원 내에서 발생한 심장정지를 치료할 때 인공순환 방법으로 사용되어 왔으며, 최근 병원 밖 심장정지가 발생하여 통상적 전문소생술에도 자발순환이 회복되지 않는 환자에게도 시행되고 있다[353637]. 그러나 심폐소생술 중 체외순환보조를 하려면, 체외순환보조에 숙련된 의료인력이 항시 대기하여야 하며, 높은 비용이 소요되기 때문에 보편적 사용에 제한이 있다. 따라서 체외순환보조소생술은 병원 내 심장정지 환자, 약물중독, 저체온, 심근염 등 가역적 원인에 의한 심장정지 환자가 심폐소생술에 의하여 자발순환이 회복되지 않는 경우에 시도한다[38].

우리나라의 심장정지 생존율은 3%에 불과하며, 생존한 환자의 2/3 이상이 심각한 신경학적 손상의 후유증을 겪는다. 심장정지는 주로 가정, 공공장소, 운동시설 등 병원 이외의 장소에서 발생하므로, 심장정지 환자가 생존하려면 목격자가 심장정지 발생을 빨리 인지하여 구조를 요청하고, 즉시 심폐소생술을 시작하여야 하며, 심실세동에 대한 신속한 제세동과 효과적인 전문소생술 및 심장정지 후 통합치료가 시행되어야 한다.

포괄적 개념의 심폐소생술은 환자를 발견한 사람이 심장정지를 인지하고 구조를 요청하며 가슴압박과 구조호흡을 함으로써 심장정지 환자의 혈액을 산소화시켜 순환시키는 과정인 기본소생술과 전문의료인이 약물투여, 제세동, 심장정지 후 통합치료를 하여 환자의 자발순환을 회복시키고 신경학적 손상을 최소화하는 전문소생술로 구성되어 있다. 개정 심폐소생술 가이드라인에서는 기본소생술 순서를 A-B-C에서 C-A-B로 변경하였으며, 고품질 가슴압박의 중요성을 강조하였다. 또한 심장정지로부터 자발순환이 회복된 환자에서 발생하는 신경학적 손상을 최소화하기 위한 저체온 치료, 심전도 상 ST절 상승이 관찰되는 환자의 경피관상동맥중재술 치료, 적정한 폐환기 조절 및 조직관류의 유지, 혈당조절 등을 포함하는 심장정지 후 통합치료가 권장되었다.

심장정지 환자의 생존율을 높이려면 심장정지에 대한 국민의 인지도 제고, 일반인에 대한 심폐소생술 교육 확대, 자동제세동기의 광범위한 보급을 포함한 정책적 접근과 심폐소생술 전반과 저체온치료를 포함한 심장정지 후 통합치료에 대한 의료인의 높은 관심이 필요하다.

우리나라는 심정지 환자수는 증가하는 반면에 생존율은 매우 낮다. 최근 심폐소생술에 관한 관심과 교육이 증가하고 있는 추세이며, 가이드라인과 새로운 개념, 치료 등의 발전으로 생존율이 점차 증가하고 있다. 본 논문은 심정지 환자의 심폐소생술에 관한 최근 가이드라인과 경향을 기술하고 있다. 심폐소생술 가이드라인의 시작에서부터 우리나라의 현황에 대하여 기술하였으며, 주기적으로 바뀌고 있는 가이드라인의 2010년 개정된 최근 지침에 대한 내용을 자세히 기술하고 있다. 또한 새로운 심폐소생술 방법에 대해서도 충분히 기술하고 있다. 따라서 심폐소생술의 최신 지견에 대한 모든 것을 한 논문 안에 요약했다는 점에서 의의가 있는 논문이라고 판단된다.

[정리: 편집위원회]

Figures and Tables

Figure 1

A schematic summary of advanced life support (see text). EGC, electrocardiogram; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; IV, intravenous; IO, intraosseous.

References

1. Myerburg RJ, Kessler KM, Castellanos A. Sudden cardiac death. Structure, function, and time-dependence of risk. Circulation. 1992; 85:1 Suppl. I2–I10.

2. Ro YS, Shin SD, Song KJ, Lee EJ, Kim JY, Ahn KO, Chung SP, Kim YT, Hong SO, Choi JA, Hwang SO, Oh DJ, Park CB, Suh GJ, Cho SI, Hwang SS. A trend in epidemiology and out-comes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest by urbanization level: a nationwide observational study from 2006 to 2010 in South Korea. Resuscitation. 2013; 84:547–557.

3. Bobrow BJ, Spaite DW, Berg RA, Stolz U, Sanders AB, Kern KB, Vadeboncoeur TF, Clark LL, Gallagher JV, Stapczynski JS, LoVecchio F, Mullins TJ, Humble WO, Ewy GA. Chest compression-only CPR by lay rescuers and survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2010; 304:1447–1454.

4. Iwami T, Kawamura T, Hiraide A, Berg RA, Hayashi Y, Nishiuchi T, Kajino K, Yonemoto N, Yukioka H, Sugimoto H, Kakuchi H, Sase K, Yokoyama H, Nonogi H. Effectiveness of bystander-initiated cardiac-only resuscitation for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2007; 116:2900–2907.

5. Kitamura T, Iwami T, Kawamura T, Nagao K, Tanaka H, Hiraide A. Implementation Working Group for the All-Japan Utstein Registry of the Fire and Disaster Management Agency. Nationwide public-access defibrillation in Japan. N Engl J Med. 2010; 362:994–1004.

6. Travers AH, Rea TD, Bobrow BJ, Edelson DP, Berg RA, Sayre MR, Berg MD, Chameides L, O'Connor RE, Swor RA. Part 4. CPR overview: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2010; 122:18 Suppl 3. S676–S684.

7. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation. JAMA. 1966; 198:372–379.

8. Hazinski MF, Nolan JP, Billi JE, Bottiger BW, Bossaert L, de Caen AR, Deakin CD, Drajer S, Eigel B, Hickey RW, Jacobs I, Kleinman ME, Kloeck W, Koster RW, Lim SH, Mancini ME, Montgomery WH, Morley PT, Morrison LJ, Nadkarni VM, O'Connor RE, Okada K, Perlman JM, Sayre MR, Shuster M, Soar J, Sunde K, Travers AH, Wyllie J, Zideman D. Part 1. Executive summary: 2010 International Consensus on Cardio-pulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations. Circulation. 2010; 122:16 Suppl 2. S250–S275.

9. Nadkarni VM, Larkin GL, Peberdy MA, Carey SM, Kaye W, Mancini ME, Nichol G, Lane-Truitt T, Potts J, Ornato JP, Berg RA. National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Investigators. First documented rhythm and clinical outcome from in-hospital cardiac arrest among children and adults. JAMA. 2006; 295:50–57.

10. Kobayashi M, Fujiwara A, Morita H, Nishimoto Y, Mishima T, Nitta M, Hayashi T, Hotta T, Hayashi Y, Hachisuka E, Sato K. A manikin-based observational study on cardiopulmonary resuscitation skills at the Osaka Senri medical rally. Resuscitation. 2008; 78:333–339.

11. Abella BS, Alvarado JP, Myklebust H, Edelson DP, Barry A, OHearn N, Vanden Hoek TL, Becker LB. Quality of cardio-pulmonary resuscitation during in-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2005; 293:305–310.

12. Abella BS, Sandbo N, Vassilatos P, Alvarado JP, O'Hearn N, Wigder HN, Hoffman P, Tynus K, Vanden Hoek TL, Becker LB. Chest compression rates during cardiopulmonary resuscitation are suboptimal: a prospective study during in-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2005; 111:428–434.

13. Berg RA, Kern KB, Sanders AB, Otto CW, Hilwig RW, Ewy GA. Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Is ventilation necessary? Circulation. 1993; 88(4 Pt 1):1907–1915.

14. Rea TD, Fahrenbruch C, Culley L, Donohoe RT, Hambly C, Innes J, Bloomingdale M, Subido C, Romines S, Eisenberg MS. CPR with chest compression alone or with rescue breathing. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363:423–433.

15. Svensson L, Bohm K, Castren M, Pettersson H, Engerstrom L, Herlitz J, Rosenqvist M. Compression-only CPR or standard CPR in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363:434–442.

16. Hasegawa K, Hiraide A, Chang Y, Brown DF. Association of prehospital advanced airway management with neurologic outcome and survival in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2013; 309:257–266.

17. Wong ML, Carey S, Mader TJ, Wang HE. American Heart Association National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resusci-tation Investigators. Time to invasive airway placement and resuscitation outcomes after inhospital cardiopulmonary arrest. Resuscitation. 2010; 81:182–186.

18. Ristagno G, Sun S, Tang W, Castillo C, Weil MH. Effects of epinephrine and vasopressin on cerebral microcirculatory flows during and after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Crit Care Med. 2007; 35:2145–2149.

19. Gueugniaud PY, David JS, Chanzy E, Hubert H, Dubien PY, Mauriaucourt P, Braganca C, Billeres X, Clotteau-Lambert MP, Fuster P, Thiercelin D, Debaty G, Ricard-Hibon A, Roux P, Espesson C, Querellou E, Ducros L, Ecollan P, Halbout L, Savary D, Guillaumee F, Maupoint R, Capelle P, Bracq C, Dreyfus P, Nouguier P, Gache A, Meurisse C, Boulanger B, Lae C, Metzger J, Raphael V, Beruben A, Wenzel V, Guinhouya C, Vilhelm C, Marret E. Vasopressin and epinephrine vs. epinephrine alone in cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:21–30.

20. Wenzel V, Krismer AC, Arntz HR, Sitter H, Stadlbauer KH, Lindner KH. European Resuscitation Council Vasopressor during Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Study Group. A comparison of vasopressin and epinephrine for out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 2004; 350:105–113.

21. Survey of Survivors After Out-of-hospital Cardiac Arrest in KANTO Area, Japan (SOS-KANTO) Study Group. Atropine sulfate for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest due to asystole and pulseless electrical activity. Circ J. 2011; 75:580–588.

22. Neumar RW, Nolan JP, Adrie C, Aibiki M, Berg RA, Bottiger BW, Callaway C, Clark RS, Geocadin RG, Jauch EC, Kern KB, Laurent I, Longstreth WT Jr, Merchant RM, Morley P, Morrison LJ, Nadkarni V, Peberdy MA, Rivers EP, Rodriguez-Nunez A, Sellke FW, Spaulding C, Sunde K, Vanden Hoek T. Post-cardiac arrest syndrome: epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prognostication. A consensus statement from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart Association, Australian and New Zealand Council on Resuscitation, European Resuscitation Council, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Council of Asia, and the Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa); the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; the Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Perioperative, and Critical Care; the Council on Clinical Cardiology; and the Stroke Council. Circulation. 2008; 118:2452–2483.

23. Peberdy MA, Callaway CW, Neumar RW, Geocadin RG, Zimmerman JL, Donnino M, Gabrielli A, Silvers SM, Zaritsky AL, Merchant R, Vanden Hoek TL, Kronick SL. American Heart Association. Part 9. Post-cardiac arrest care: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010; 122:18 Suppl 3. S768–S786.

24. Hosmane VR, Mustafa NG, Reddy VK, Reese CL 4th, Di-Sabatino A, Kolm P, Hopkins JT, Weintraub WS, Rahman E. Survival and neurologic recovery in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction resuscitated from cardiac arrest. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 53:409–415.

25. Kern KB, Rahman O. Emergent percutaneous coronary intervention for resuscitated victims of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010; 75:616–624.

26. Bernard SA, Gray TW, Buist MD, Jones BM, Silvester W, Gutteridge G, Smith K. Treatment of comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:557–563.

27. Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Study Group. Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:549–556.

28. Holzer M. Targeted temperature management for comatose survivors of cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363:1256–1264.

29. Oddo M, Ribordy V, Feihl F, Rossetti AO, Schaller MD, Chiolero R, Liaudet L. Early predictors of outcome in comatose survivors of ventricular fibrillation and non-ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest treated with hypothermia: a prospective study. Crit Care Med. 2008; 36:2296–2301.

30. Italian Cooling Experience (ICE) Study Group. Early-versus late-initiation of therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest: preliminary observations from the experience of 17 Italian intensive care units. Resuscitation. 2012; 83:823–828.

31. Taccone FS, Donadello K, Beumier M, Scolletta S. When, where and how to initiate hypothermia after adult cardiac arrest. Minerva Anestesiol. 2011; 77:927–933.

32. Knapik P, Rychlik W, Duda D, Golyszny R, Borowik D, Ciesla D. Relationship between blood, nasopharyngeal and urinary bladder temperature during intravascular cooling for therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2012; 83:208–212.

33. Ong ME, Ornato JP, Edwards DP, Dhindsa HS, Best AM, Ines CS, Hickey S, Clark B, Williams DC, Powell RG, Overton JL, Peberdy MA. Use of an automated, load-distributing band chest compression device for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest resuscitation. JAMA. 2006; 295:2629–2637.

34. Aufderheide TP, Frascone RJ, Wayne MA, Mahoney BD, Swor RA, Domeier RM, Olinger ML, Holcomb RG, Tupper DE, Yannopoulos D, Lurie KG. Standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation versus active compression-decompression cardiopulmonary resuscitation with augmentation of negative intrathoracic pressure for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2011; 377:301–311.

35. Chung JW, Chang WH, Hyon MS, Youm W. Extracorporeal life support after prolonged resuscitation for in-hospital cardiac arrest due to refractory ventricular fibrillation: two cases resulting in a full recovery. Korean Circ J. 2012; 42:423–426.

36. Kagawa E, Inoue I, Kawagoe T, Ishihara M, Shimatani Y, Kurisu S, Nakama Y, Dai K, Takayuki O, Ikenaga H, Morimoto Y, Ejiri K, Oda N. Assessment of outcomes and differences between in- and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients treated with cardiopulmonary resuscitation using extracorporeal life support. Resuscitation. 2010; 81:968–973.

37. Chen YS, Lin JW, Yu HY, Ko WJ, Jerng JS, Chang WT, Chen WJ, Huang SC, Chi NH, Wang CH, Chen LC, Tsai PR, Wang SS, Hwang JJ, Lin FY. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation with assisted extracorporeal life-support versus conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation in adults with in-hospital cardiac arrest: an observational study and propensity analysis. Lancet. 2008; 372:554–561.

38. Conseil francais de reanimation cardiopulmonaire. Societe francaise d'anesthesie et de reanimation. Societe francaise de cardiologie. Societe francaise de chirurgie thoracique et cardiovasculaire. Societe francaise de medecine d'urgence. Societe francaise de pediatrie. Groupe francophone de reanimation et d'urgence pediatriques. Societe francaise de perfusion. Societe de reanimation de langue francaise. Guidelines for indications for the use of extracorporeal life support in re-fractory cardiac arrest. French Ministry of Health. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2009; 28:182–190.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download