Introduction

Population of the elderly in Korea had reached 10.7% of the total population in 2009 [1]. Korea has already entered into a aging society of the elderly over 65 has reached above 7% of the total population. And it has been estimated that the percent will reach 14% in 2018. Social activities of the aged persons have become quite active as the population increases. Trauma in the elderly, such as facial bone fractures, has been increasing [2-4].

In Korea, a variety of policies have been prepared after the law of Old Age Security Act was revised in 1997. Nevertheless, it is quite difficult to find any studies of the facial trauma of the elderly. There was a study from our hospital in 2006 about facial bone fractures in 87 elderly patients [3]. However, we felt that more studies of the recent changes were necessary.

The purpose of this study was to determine the pattern of facial bone fractures in the elderly in a tertiary hospital in Daegu and to provide literature basis of the preventive strategies in aging society.

Patients and Methods

1. Patients

Retrospective analyses were conducted on clinical records for facial bone fractures in 474 cases from 300 patients aged 55 years or older. They were treated at the Department of Plastic Surgery, Yeungnam University Hospital between January 2006 and December 2010. The follow-up period was from a month to 48 months after injury. The mean follow-up period was 9.32 months.

2. Methods

Clinical records of the elderly with facial bone fracture were reviewed and data related to sex, age, occupation, area of residence, time, etiology, site and multiplicity of fractures, combined soft tissue injuries, treatment methods and sequelae were assessed.

The age of the patients was divided into five age groups: 55 to 59, 60 to 64, 65 to 69, 70 to 74, and 75 years or older. The time of the accidents was classified according to the day of the week, and the year. The etiology of the facial bone fracture were classified as traffic accident, slip down, fall down, assault, industrial injury and others.

The facial bone fractures were classified into their site, such as frontal bone fracture, orbital wall fracture, zygomatic fracture, nasal bone fracture, maxillary fracture, palatine bone fracture and mandiblular fracture. Associated injuries of brain, spine, chest, abdomen, extremities were checked. Combined soft tissue injuries were also assessed. Open reduction, closed reduction and conservative treatment in each case were also assessed.

The sequelae after the fractures were identified functionally as well as aesthetically. The functional problems were comprised of diplopia, extraocular muscle limitation, visual loss, epiphora, nasal stiffness, anosmia, paresthesia, malocclusion, mouth opening limitation, facial palsy, and the aesthetic problems were comprised of enophthalmos, ectropion, nasal and malar asymmetry. In detail, the mouth opening limitation was defined that the cases were maximum interincisal opening of less than 30 mm, and the enophthalmos was defined that the cases of more than 2 mm in difference of corneal projection. The facial asymmetry was checked when patients raised that complaints.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS ver. 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The chi-square test was used to determine statistical differences of the results. Values of P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

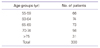

2. Age

Among the age groups, patients in the age range of 65-74 years old were the most common. Next, 73 injuries in the age group of 65 to 69 (Table 1).

3. Occupation and area of residence

The farmers and agricultural support personnels were 136 (45.3%). The unemployed were 115, blue collar were 28, white collar were 21. One hundred twenty (40.0%) patients were lived in urban areas, and 180 (60.0%) patients in rural areas.

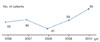

4. Yearly, monthly, and weekly distribution

The number of the patients increased each year except in 2008 (Figure 1). The monthly distribution revealed high incidences during August (40 patients), October (39 patients). February figures were lowest (13 patients). According to the weekly analyses, it showed 54 patients on Monday, 50 on Wednesday which was the most. Thirty-six on Saturday was the smallest.

5. Cause

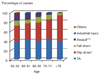

Main causes of fractures were traffic accident (48.0%), slip down (34.0%), and fall down (9.6%). Among the traffic accident cases, 17.7% was due to motorcycle accidents, 12.3% was in-car accidents, 11.7% was pedestrian accidents, and 6.3% was cultivator accidents, respectively. The percentage of the slip down has shown on its increase while the patients get older (Figure 2). However, the assault decreased consistently with age. The graph in Figure 2 shows that there was significant difference in rate of slip down (P=0.029) and assault (P<0.001) according to the age. In the age group of 55 to 69, the percentage of the traffic accident was higher than that of the slip down. The slip down was most common cause of injury among the patients aged 70 years or older (Figure 2).

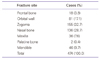

6. Site and multiplicity of fracture

Among facial bone fractures, zygomatic fractures were 32.7%, which was the highest among all fracture types, then followed by in the order of nasal bone fractures, orbital wall fractures, mandibular fractures, and maxillary fractures (Table 2). One hundred twenty-two patients (40.7%) were involved in cases where two or more types of fractures occurred concurrently, and 178 patients (59.1%) were involved in cases with only one type of facial bone fracture.

8. Soft tissue injury combined with facial bone fractures

One hundred and fifty patients had a facial bone fractures combined with soft tissue injuries such as laceration, canaliculi injury, facial nerve palsy, avulsion injury, etc.

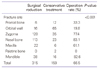

9. Treatment method

The surgical reduction was performed on 66.5% of all facial bone fracture patients. Table 4 shows that there was significant difference in operation rate according to the site of facial bone fractures (P<0.001). Eighty-three percent of the nasal bone fractures, 82.6% of the mandibular fractures and 77.4% of the zygomatic fractures were treated with surgical reduction. Only 19.8% of the orbital wall fractures and 33.3% of the frontal bone fractures were treated with surgical reduction.

10. Sequelae

In the functional problems, there were 49 cases of paresthesia and 4 cases of epiphora. In the aesthetic problems, there were 7 cases of nasal asymmetry, 4 cases of malar asymmetry and 4 cases of enophthalmos (Table 5).

Discussion

There are many articles about facial bone fractures from various medical centers [2-11]. The studies of each center have distinctive attribute. In the data from school of dentistry, most common site of the facial bone fracture was mandible [5]. The mandibular fracture was subdivided and investigated in detail [5]. In the study from National Police Hospital, intended injury was most common etiology [6]. From the emergency medicine article about facial bone fractures, initial physical exam was important place in the results and conclusion [7]. In this study, facial bone fractures in the elderly discussed in a view of biological aspect. The effect of osteoporotic change on the management of facial bone fractures and the issue about definition of an elderly would be discussed.

Osteoporotic changes are caused by reduction in bone formation from the periosteum, reduction of bone volume taken place in basic multicellular unit, autogenic cortical bone thickness reduction caused by constant bone resorption, and increase in postmenopausal bone turnover [12]. Osteoporotic changes in the aged persons significantly influence on the decision of the treatment strategies for the facial bone fracture of the patients. It is preferred to perform open reduction and internal fixation for facial bone fractures of the old age patients with bone atrophy and osteoporotic changes [2].

In discussing the facial bone fractures of the elderly, it is important to define how old the elderly should be to qualify an aged person, because it will influence not only the statistical numbers but also contents of the conclusion. Previous studies have been conducted on the facial bone fractures of patients of 60 or 65 years or older, however their ages were not discussed specifically [2,4,8]. In order to define the elderly, not only physiologic aspects but also sociocultural aspects should be taken into account.

Decrease of cortical bone begins to show among all males as well as females after 50 years or older [13]. Total mass of the bone begins to decrease from young adulthood, and this is because about 40% of the trabecular bone lost across life is lost before the age of 50 years. As the age increases, mineral deposit in collagen making its elasticity decrease and making it unable to absorb external forces, causing fractures. Actual loss of bone occurs after 45 years old in the case of females, and after 50 years old in the case of males [13]. Fluid intelligence, such as problem solving, spatial manipulation, mental speed, identifying complex relation begins to gradually decrease after mid-twenties and suddenly decreases after sixty years old, and they are influenced by genetic factors, physiologic aging [14]. And after sixties, speed of negative changes will increase and it is the period of coming out of the mainstream of social activities [15]. Based upon the concept of aging and its physiological, social and psychological aspects, patients of 55 years or older were investigated in this study.

Sex distribution was 75% for 225 male patients and 25% for 75 female patients. According to the survey by the National Statistical Office of Korea for the period of 2006 to 2010, among the population of 55 years or older, 3.76 millions were males (44%) and 4.77 millions were females (56%) [1]. Based on these facts, actual accident rate for males was higher than three times that of females. Considering the causes for the fractures such as traffic accident, slip down, fall down, etc., one can find that the reason for the higher accident ratio for the males is the fact that males are more active than females in their old ages [4].

There are few studies about the occupation of the aged patients of facial bone fractures. As for the number of patients per occupation, those that did not have any particular occupations but lived on the farm in a life style similar to that of the farmers' were classified as agricultural support personnel, and the number of these people was added up to the number of the farmers totaling 136, which was the highest compared to other occupations. This number was closely looked into by the month, and it was found that most fracture accidents had happened during the months of April, August and October, coinciding with the busy months on the farm. Actually, most injuries to the agriculture support personnel were caused by the cultivator traffic accidents, slip down into the rice paddies, injury by the weeder blade, as well as by being hit by the bull's horn.

In our study, traffic accidents and slip down were the main causes of facial bone fracture, however, traffic accidents and assault were the predominant causes according to the other studies on all age groups [9,10]. The reason that slip down followed next was due to the progression of aging, such as physical degradation, decrease in sense of balance and space perception ability. The finding that traffic accidents and slip down account for 81% of the total number of the aged could be a significant information for the prevention of facial bone fractures of the elderly.

Generally, distal fracture of the radius (Colles' fracture) was known as most common fracture in the elderly and young adult population [16]. Nasal bone fracture was most common in facial bone fracture [17]. In our study, the zygomatic fractures showed highest rate (32.7%) compared to other facial bone fractures. It seems to be because the slip down is more common cause of facial bone fractures in this study than that of young people. When a accident like slip down occurred, a man would turn his head in a moment because of the reflex. Therefore, the zygoma on the lateral side of face has more chances of injuries. And the elderly people of low socioeconomic state don't visit to a hospital at minor trauma such as nasal bone fracture.

The multiple facial bone fractures, at the study of all age groups showed for 32.0% of the total facial bone fracture patients [11]. In this study showed a higher rate, that is 40.7%. The facial bone fractures were combined with soft tissue injuries in 50.0% of the total patients. These figures are much higher than 13.4% in a study of all age groups [10].

As for combined soft tissue injuries, there were facial laceration, canaliculi injury, facial nerve injury, soft tissue defect, etc., and facial bone fractures were combined by soft tissue injuries in 50% of the total patients. These figures are much higher than that reported in a study on all age groups [10].

The authors treated the facial bone fractures of aged persons under the principles of emergency one-stage repair, exposure of all fracture fragments, precise anatomic rigid fixation and immediate bone grafting. However, in the cases of poor general conditions or life-threatening combined injuries, the operation was delayed or conservative treatment was done. The operation was minimally dissected, preserved the periosteum.

As far as patients' sequelae investigated in this study were concerned, functional problems accounted for a great deal of weight. The reason might be that their interest in the matter of appearance would have not been as great as that of the young patients'. Some of the sequelae, such as paresthesia, diplopia, mouth opening limitation, disappeared during the follow-up periods, and they were excluded. It is often difficult to follow up elderly patients because they cannot make a required visit due to their general condition and limited transportation means, as well as reduced life span. Therefore, sequelae cannot be evaluated properly, especially in patients who treated with conservative method.

Underlying diseases of the elderly are the important elements that determines the period of the hospitalization [2]. In this study there was no investigation made as to the period of the hospitalization, and additional study should be conducted in this point. The patients of this study live in and around the major city but non-Seoul metropolitan area. The results of this study have regional limitation. It is difficult that a single medical center like the hospital that this study carried on has representability. Therefore, future studies are needed to get the data from muticenter clinical trials.

Conclusion

The causes of facial bone fractures in the elderly are multifactorial, however traffic accidents and slip downs account for more than four-fifth of all cases. Under-standing these risk factors could help to establish preventive strategies and policy. In this study, 66.5% of all patients needed surgical treatment. It is lower incidence than that of all age groups. therefore conservative treatment should be considered as a instrumental option in the elderly unless a functional deficit is present.

Gathering information on facial bone fractures in the elderly is necessary and valuable information. More accurate and recent analyses on the facial bone fractures in the elderly identified in this study will contribute to the prevention of fractures and establishing long term plans.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download