Abstract

A 1.6-year-old male domestic short hair cat was brought to the Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, Kasetsart University, with signs of severe anemia, depression, and general lymph node enlargement. Complete blood count revealed leukocytosis and massive undifferentiated blasts. Testing for antibodies specific to feline leukemia virus (FeLV) was positive, and FeLV nucleic acid was confirmed by nested polymerase chain reaction. Base on cytochemistry and ultrastructure, the cat was diagnosed with acute monoblastic leukemia.

Feline leukemia virus (FeLV) is a retrovirus that causes a wide range of proliferative diseases in cats, including lymphoid and myeloid leukemia [6]. Acute myeloid leukemia may be misinterpreted as acute lymphoid leukemia if the blast cells are classified using only Romanowsky stained smears [10]. Cytochemical staining has been employed to aid in the differentiation of acute leukemias [2]. Assessment of cell ultrastructure by transmission (TEM) or scanning electron microscope (SEM) has also been used to enhance the magnitude of cell identification, especially with poorly differentiated cells [1]. Although FeLV is a common infectious disease in young cats, no clinical cases ofacute monoblastic leukemia in FeLV-infected cats in Thailand have been reported previously. In the present report, a case of acute monoblastic leukemia in a FeLV-positive cat is described.

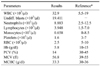

A 1.6-year-old male domestic short hair cat was brought to the Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Kasetsart University, with a history of anemia, depression, and weight loss. Physical examination revealed dyspnea, as well as cervical, axillary, and popliteal lymph node enlargement. The initial laboratory tests included a complete blood count (CBC) and serological test (Fast Test FeLV; MegaCor Diagnostic, Austria). The CBC is summarized in Table 1, and shows severe anemia, thrombocytopenia, and marked leukocytosis with undifferentiated blasts in more than 50 percent. Morphologically, these cells were round to ovoid in shape, with finely stippled nuclear chromatin and distinct nucleoli (Figs. 1A and B). Some presented prominent cytoplasmic tails (Fig. 1C). The serological test was positive for FeLV. Further examination using nested polymerase chain reaction, as described elsewhere [9], also confirmed the presence of FeLV nucleic acid in the blood. The initial treatment was started with 1 mg/kg dexamethasone IV and fluid therapy (5% dextrose in half-strength saline), with oxygen being given all day.

Although a bone marrow examination was recommended, the poor condition of the patient limited this procedure. To further classify undifferentiated blasts, selected cytochemical staining was performed, including peroxidase (PER), Sudan black B (SBB), α-naphthyl acetate esterase (ANAE), periodic-acid Schiff [4], and β-glucuronidase (β-GLU) [3]. Five hundred cells from each of the cytochemically-stained smears were counted following staining in which positive- and negative-stained cells were differentiated. For SEM and TEM, blood cells were processed as described elsewhere [11]. Identification of blasts by SEM and TEM was based on the relative number, size, shape, cytoplasmic complexity, and nuclear appearance.

Unfortunately, the owner denied the hospital from admitting the cat. Three days later, the cat died and his carcass was submitted to necropsy. The hallmark lesions showed splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, and enlargement of several lymph nodes. Histopathologically, massive neoplastic cells contained round, finely chromatic nuclei; amphophilic cytoplasm infiltrated these organs.

Detection using ANAE and β-GLU staining yielded 100% positive blasts (Figs. 1G and H), while PER, SBB, and PAS stains revealed only a few positive cells (Figs. 1D, F and I). The cytochemical profiles are summarized in Table 2. Using SEM, the blasts appeared round to ovoid in shape with a ruffled membrane and deep fissures, whereas pseudopodia were clearly observed (Figs. 2A and B). Ultrastructurally, a round to irregular nuclear shape with marginated nuclear chromatin and light cytoplasmic appearance with some electron-dense granules and organelles such as endoplasmic reticulum cisternae were shown (Figs. 2C and D). From these results, the patient was diagnosed acute monoblastic leukemia.

Definitive diagnosis of acute leukemia requires a panel of cytochemical and electron microscopic analysis. A panel of cytochemical stains of blood smears can be applied in order to determine the lineage of leukemic cells. In addition, SEM can be used to evaluate cell surfaces while TEM presents the ultrastructural images of organelles. The most useful cytochemical stain in monoblastic leukemia is the reaction for nonspecific esterase activities such as ANAE [5], while SBB- and PER-positive patterns support the myeloid lineage.

Though the most common form of leukemia in cats infected with FeLV is of the lymphoid lineage [12], a myeloid lineage was the affected progenitor subset found in the patient described in this study. This finding may be due to retrovirus-induced chromosomal translocation involving chromosome 11q 23, and rearrangement of a gene referred to as myeloid/lymphoid or mixed lineage leukemia at the translocation breakpoint [7,8].

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Morphologies and cytochemical stainings of undifferentiated blasts: (A and B) blasts were round to ovoid in shape with finely stippled nuclear chromatin and distinct nucleoli (Wright-Giemsa stain); (C) a blast with a prominent cytoplasmic tail (Wright-Giemsa stain); (D) a blast that stained positive for peroxidase; (E) a blast that was negatively stained for Sudan black B (left) compared to a positively-stained granulocyte (right); (F) a blast with positive Sudan black B staining; (G) a blast that was strongly positive for α-naphthyl acetate esterase; (H) a blast that was moderately positive for β-glucuronidase; (I) a blast that was positive for PAS.

Fig. 2

Cellular surfaces and ultrastructures of blasts: (A and B) Ruffled membrane with deep fissures and pseudopodic projection (SEM); (C) Indented nucleus with marginated chromatin and light cytoplasm with some electron dense granules and organelles (left) adhered to a plasma cell (right) (TEM); (D) High magnification of (C) showing the organelles and granules.

References

1. Grindem CB. Ultrastructural morphology of leukemic cells from 14 dogs. Vet Pathol. 1985. 22:456–462.

2. Grindem CB, Stevens JB, Perman V. Cytochemical reactions in cells from leukemic dogs. Vet Pathol. 1986. 23:103–109.

3. Hayhoe FGJ, Quaglino D. Hematological Cytochemistry. 1980. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone;68–75.

4. Jain NC. Schalm's Veterinary Hematology. 1986. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger;1221.

5. Kass L. Leukemia, Cytology and Cytochemistry. 1982. Philadelphia: Lippincott;167–188.

6. Khan KNM, Kociba GJ, Wellman ML. Macrophage tropism of feline leukemia virus (FeLV) of subgroup-C and increased production of tumor necrosis factor-α by FeLV-infected macrophages. Blood. 1993. 81:2585–2590.

7. Kohlmann A, Schoch C, Dugas M, Schnittger S, Hiddemann W, Kern W, Haferlach T. New insights into MLL gene rearranged acute leukemias using gene expression profiling: shared pathways, lineage commitment, and partner genes. Leukemia. 2005. 19:953–964.

8. Kuwada N, Kimura F, Matsumura T, Yamashita T, Nakamura Y, Wakimoto N, Ikeda T, Sato K, Motoyoshi K. t(11;14)(q23;q24) generates an MLL-human gephyrin fusion gene along with a de facto truncated MLL in acute monoblastic leukemia. Cancer Res. 2001. 61:2665–2669.

9. Miyazawa T, Jarrett O. Feline leukaemia virus proviral DNA detected by polymerase chain reaction in antigenaemic but non-viraemic ('discordant') cats. Arch Virol. 1997. 142:323–332.

10. Prihirunkit K, Kasorndokbua C, Apibal S. Diagnosis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a dog by cytochemistry. J Thai Vet Pract. 2005. 17:53–61.

11. Salakij C, Salakij J, Apibal S, Narkkong NA, Chanhome L, Rochanapat N. Hematology, morphology, cytochemical staining, and ultrastructural characteristics of blood cells in king cobras (Ophiophagus hannah). Vet Clin Pathol. 2002. 31:116–126.

12. Thrall MA. Lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphocytic leukemia and plasma cell myeloma. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1981. 11:321–347.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download