Abstract

A 4-year-old female Barbary sheep (Ammotragus lervia) was found dead in the Gwangju Uchi Park Zoo. The animal had previously exhibited weakness and lethargy, but no signs of diarrhea. The carcass was emaciated upon presentation. The main gross lesion was characterized by severe serous atrophy of the fat tissues of the coronary and left ventricular grooves, resulting in the transformation of the fat to a gelatinous material. The rumen was fully distended with food, while the abomasum evidenced mucosal corrugation with slight congestion. Microscopic examination revealed the presence of Balantidium coli trophozoites within the lymphatic ducts of the gastric lymph node and the abdominal submucosa. On rare occasions, these organisms may invade extra-intestinal organs, in this case the gastric lymph nodes and abomasum.

Balantidiasis is an infectious disease which occurs worldwide, and is caused by the protozoan, Balantidium coli. This single-celled organism is characterized primarily by its large size, which ranges from 50 µm to over 500 µm, including the cilia on its cell surface [4]. This parasite has been detected in the lumen of the cecum and the colon of swine, humans, and nonhuman primates as a commensal organism, but can become a pathogenic opportunist via the invasion of tissues that have been previously damaged by other diseases [5]. The clinical diagnosis of this disease has proven somewhat difficult, as it is asymptomatic and can be complicated by other diseases or parasites [10]. Here, we report the incidental detection of Balantidiasis within the gastric lymph ducts of a Barbary sheep (Ammotragus lervia).

The subject of this case was a member of a herd resident in the Gwangju Uchi Park Zoo in Gwangju City, Korea. The affected herd contained a total of 10 animals, 5 of which had suffered from arthritis and lameness. Two of the affected animals died, and the case specifically described in this study was one of these 2 animals.

The initial examination of the animal revealed that the aforementioned lameness and arthritis was the result of foot rot induced by Fusobacterium necrophorum, which was isolated from the lesion site. As the result of this weakness, the animal grew increasingly lethargic, and finally succumbed and perished. The results of the external examination of the carcass clearly indicated emaciation and dehydration. The necropsy examination also revealed a serous atrophy of subcutaneous fat and fat deposits along the coronary and left ventricular grooves of the heart (Fig. 1). Fecal samples were collected from the ileum and colon for parasite examination. The mucosa of the abomasum was moderately congested and partially corrugated, whereas the gastric lymph nodes were mildly enlarged. The tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. The paraffin-embedded sections of the lymph nodes were cut at 4 µm, and were stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

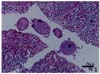

The histopathological examination of the gastric lymph nodes and the abomasum revealed the presence of a few Balantidium coli trophozoites within the ducts and submucosa (Fig. 2). A few distorted anucleated trophozoites were also detected (Fig. 3). B. coli was characterized by its spherical shape (40-60 µm) with a hyaline wall and large macronucleus, which could be seen within. The characteristic two nuclei of the protozoan parasite were clearly visible. The macronucleus was long and kidney-shaped, and the spherical micronucleus was nestled adjacent to it.

No B. coli trophozoites or cysts were detected in the feces, but we did note a heavy infestation of Eimeria spp. oocysts, Trichuris sp. and Strongyloides sp.. Oocysts normally break out of the epithelial lining of the intestine, and are then passed via the feces of the infected animal. Each stage coccidial development within the animal inflicts physical damage. As opportunist organisms, Balantidium coli trophozoites tend to become invasive, and penetrate the mucosal lining of the damaged intestine, from which they travel throughout the rest of the body. In this case, the absence of Balantidium cysts can probably be attributed to an incomplete encystations cycle.

The diagnosis, in this case, was predicated on the detection of trophozoites or cysts in the feces, and also in the tissues. Balantidium can be recognized in tissues primarily by its large size, ovoid shape, the presence of a dense curved or kidney-shaped macronucleus, and the presence of cilia arranged in rows on the surface [5]. Under favorable conditions, Balantidium invades and penetrates the compromised mucosal lining prior to localizing within certain lymphoid tissues [4]. The penetration of the mucosal lining results in varying degrees of acute inflammation within the general vicinity of the penetration site, and may culminate in some manifestations of enteric disease.

Little data is currently available regarding Ammotragus lervia parasitism in animals in captivity. B. coli has been detected in 7.7% of fresh fecal sample collected from wild De Brazza's monkeys (Cercopithecus neglectus) in Kenya [6], and 19.3% of fecal sample collected from local cross-bred pigs in the upper East Region of Ghana [9]. The prevalence of B. coli in wild boars in Western Iran was approximately 25%, but other amoebic cysts can complicate these findings [12]. In this case, no trophozoites were detected in the feces, although this is not an uncommon finding. The trophozoites travel down to the large intestine, in which they normally reproduce via binary fission within the lumen. The presence of coccidian oocysts made it possible for them to invade the damaged tissue, and to localize within the ducts of the gastric lymph nodes.

A secondary invader, Balantidium travels throughout the body via several specific routes. It is possible for this organism to perforate the large intestine prior to migration into the small intestine [3], appendix [2], vagina, uterus, and bladder [7] and, rarely, into the liver [14] and lungs [1,11,13]. Balantidium is also known to generate hyaluronidase, which allows them to effect an enlargement of the lesions by attacking the ground substance between the cells. It is fairly common to detect organisms which nest within the tissues, or even in the capillaries, lymph ducts, and neighboring lymph nodes or tissue [8].

The presence of heavy infestations of endoparasites in these animals indicated that they were under stressed conditions, which ultimately culminated in lymphocytic dysfunction. Balantidium infection rates are also likely to be fairly high in pigs, in which immunodeficiency can result in the exacerbation of the disease [1]. The immunocompromise of animals as the result of the stress inherent to heavy endoparasitic infestation might explain why Balantidium could be detected in the gastric lymph ducts and mucosa of the abomasum in the absence of eosinophils or other inflammatory cells within the adjacent tissues. We suggest that the trophozoites traveled to the abomasum and invaded the submucosa, until they had reached the gastric lymph ducts. This, however, is currently only a hypothesis, and remains to be proven, due to the fact that this report chronicles an incidental finding, and the first reported case of Balantidiasis in the Barbary sheep (Ammotragus lervia).

Figures and Tables

References

1. Anargyrou K, Petrikkos GL, Suller MT, Skiada A, Siakantaris MP, Osuntoyinbo RT, Pangalis G, Vaiopoulos G. Pulmonary Balantidium coli infection in a leukemic patient. Am J Hematol. 2003. 73:180–183.

2. Arean VM, Koppisch E. Balantidiasis: a review and report of cases. Am J Pathol. 1956. 32:1089–1115.

3. Baskerville L, Ahmed Y, Ramchad S. Balantidium colitis. Am J Dig Dis. 1970. 15:727–731.

4. Jones TC, Hunt RD, King NW. Veterinary Pathology. 1997. 6th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins;583.

5. Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N. Pathology of Domestic Animals. 1997. Vol. 2:6th ed. New York: Academic Press;317–318.

6. Karere GM, Munene E. Some gastro-intestinal tract parasites in wild De Brazza's monkeys (Cercopithecus neglectus) in Kenya. Vet Parasitol. 2002. 110:153–157.

7. Knight R. Giardiasis, isosporiasis and balantidiasis. Clin Gastroenterol. 1978. 7:31–47.

8. Levine ND. Veterinary Protozoology. 1985. Ames: Iowa State University Press;361–362.

9. Permin A, Yelifari L, Bloch P, Steenhard N, Hansen NP, Nansen P. Parasites in cross-bred pigs in the upper East Region of Ghana. Vet Parasitol. 1999. 87:63–71.

10. Rubin E, Farber JL. Pathology. 1999. 3rd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins;455.

11. Sharma S, Harding G. Necrotizing lung infection caused by the protozoan Balantidium coli. Can J Infect Dis. 2003. 14:163–166.

12. Solaymani-Mohammadi S, Rezaian M, Hooshyar H, Mowlavi GR, Babaei Z, Anwar MA. Intestinal protozoa in wild boars (Sus scrofa) in Western Iran. J Wildl Dis. 2004. 40:801–803.

13. Vasilakopoulou A, Dimarongona K, Samakovli A, Papadimitris K, Avlami A. Balantidium coli pneumonia in an immunocompromised patient. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003. 35:144–146.

14. Wegner F. Abscesso hepatico producido por el Balantidium coli. Casemera. 1967. 2:433–441.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download