Abstract

A twenty-month-old Chihuahua male dog was presented to us suffering with ataxia. Based on the physical examination, X-ray and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examinations, we diagnosed the dog with hydrocephalus, Chiari I malformation and syringomyelia. Treatment consisted of internal medical treatment and the placement of a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt. The ventricular dilatation was relieved and the dog improved neurologically; however, the Chiari I malformation and syringomyelia remained after surgically positioning the VP shunt.

Hydrocephalus is the term commonly used to describe a condition of abnormal dilation of the ventricular system within the cranium. Ventricular dilation occurs in dogs because of a variety of intracranial disease processes [4]. The choice of treatment is generally dictated by the physical status, the age of the animal and the cause of the hydrocephalus. Medical treatment may include general supportive care and administering medications to limit the production of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and so reduce the intracranial pressure. Surgery is generally required for those animals that do not improve within 2 weeks and ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunts are most commonly used in small animals [10]. This paper describes a dog suffering with hydrocephalus that underwent VP shunting.

A twenty-month-old Chihuahua male dog was presented to the Yamaguchi University Veterinary Medical Hospital (YUVMH) with ataxia. The owner reported that the dog once foamed at the mouth 8 months ago and the dog's gait consisted of swaying with short strides; the walking symptoms had waxed and waned in the last week. The dog had received its vaccinations and had recently been started on a regiment of oral dexamethasone (0.5 mg per dog, SID) by the referring veterinarian.

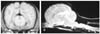

Upon presentation to the YUVMH, the dog appeared normally conscious, but ataxic and weak, and it had a dome-shaped calvarium. The open fontanelle was palpated. There were no abnormalities on the neurological examination, including evaluation of the postural reaction and spinal reflex, but there was a weak reaction in the papillary light reflex and no reaction for the menace response was observed. A complete blood count (CBC) revealed that all the values were within the normal range. The serum biochemistry abnormalities included elevation of alanine aminotransferase (ALT; 224 IU/l, reference range: 13 to 53 IU/l) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP; 167IU/l, reference range: 0 to 142 IU/l), and mild hypokalemia (3.2 mEq/l, reference range: 3.4 to 5.2 mEq/l). An x-ray examination revealed a mildly enlarged skull, an open fontanelle and partial protrusion of the occipital bone (Fig. 1). MRI (Hitachi MRP-20; Hitachi, Japan) revealed asymmetrically enlarged lateral ventricles and slight dilation of the third ventricle (Fig. 2). We also found syringomyelia in the region of C2, 3 and 4 and caudal (foramen magnum) descent of the cerebellum (Chiari I malformation). A diagnosis of hydrocephalus was made and medical treatment (dexamethasone 0.1mg per dog, acetazolamide 5 mg/kg, furosemide 1 mg/kg, BI) was first administered.

The owner reported a few days later that the dog did not show any improvement of the clinical signs and it showed more frequent episodes of ataxia, stupor and partial seizure. After consulting with the owner, the decision was made to surgically place a VP shunt in order to divert the excess fluid in the cranial vault to the peritoneal cavity.

The VP shunt (LPV II Valves and Kits; Heyer-Schulte Neurocare, USA) was placed using the method described by Bagley [1] and Harrington et al. [4]. The ventricular catheter was placed into the left lateral ventricle through the parietal bone and the distal end of the catheter was implanted into the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 3).

Seven days after the surgery, the dog recovered and it was neurologically normal; the dog was discharged 2 weeks later. Four moths after surgery, the MRI (Fig. 4) revealed that dilation of the ventricles was relieved, but the Chiari I malformation and the syringomyelia remained intact.

Hydrocephalus may be classified into a primary or secondary condition, and it does not always result in clinical signs and symptoms. Primary (congenital) hydrocephalus is apparently due to failure of the arachnoid villi to reabsorb CSF at an adequate rate. Other cases of congenital hydrocephalus involve a narrowed mesencephalic aqueduct with obstruction of the CSF flow. The most common clinical findings in the patients with hydrocephalus include: seizures, visual deficits, slowed learning and dementia. Secondary (noncomunicating) hydrocephalus results from impaired CSF movement. This may be due to ventricular obstruction (e.g., secondary to neoplasms) or to impaired CSF resorption at the arachnoid villi, and this is usually as a consequence of prior inflammation. Although the clinical course for congenital hydrocephalus is usually slowly progressive, secondary hydrocephalus is often rapidly progressive and it's associated with a massive elevation of the intracranial pressure [3].

In this case, a Chihuahua dog with a dome-shaped calvarium was presented with ataxia. Chihuahuas are predisposed to congenital hydrocephalus and this malady is most often seen in young dogs, prior to ossification of the cranial sutures. Hydrocephalus may contribute to abnormalities of skull development such as a thinning of the bone structure, a dome-shaped or bossed appearance to the head or a persistent fontanelle [10].

The dog was treated with dexamethasone, acetazolamide and frosemide before VP shunting. Steroids are known to increase CSF resorption, and diuretics diminish CSF production [10]. However, there has been only limited success for the long-term therapy of primary hydrocephalus with using maintenance prednisone. Short-term administration of diuretics may decrease the intracranial pressure, but their long-term use may be associated with systemic electrolyte disturbances [3].

On the MRI examination, we found not only asymmetric dilatation of the lateral ventricles, but also Chiari I malformation and syringomyelia (Fig. 2). Chiari I malformation is a disorder of an uncertain origin that has been traditionally defined as the downward herniation of the cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum [9]. Syringomyelia is a cystic cavity of the spinal cord that contains fluid identical or similar to the CSF and extracellular fluid (ECF). The cavity may be formed by a dilatation of the central canal or it may lie within the parenchymal substance [8]. Chiari I malformation is a leading cause of syringomyelia [9], however, the pathogenesis of syringomyelia associated with Chiari I malformation is still not fully understood.

In this case, the dog had an open fontanelle and a very thin skull, so it was difficult to place the ventricular catheter into the lateral ventricle. We used coagulants (carbazochrome sodium sulfonate, tranexamic acid) and antibiotics (cefazolin, cephalexin) following surgery to control infection and hemorrhage, which are the most common causes of shunt obstruction [6]. There are some reports of VP shunting complications such as inadequate drainage, infection, overdrainage and seizures [5,6,7,11]. Overshunting may lead to slit-ventricle syndrome, low intracranial pressure syndrome, subdural hematoma or hydroma, craniostenosis, microencephaly and aqueduct stenosis or obstruction. Continuous efforts and adequate treatment should be carried out to overcome these possible complications.

After VP shunting surgery, the dog did not show any neurological abnormalities; however, Chiari I malformation and syringomyelia still remained. Thus, we can suggest that the ataxia was mainly a result of hydrocepahalus and that Chiari I malformation and syringomyelia did not contribute to the clinical disorders in this case. Some papers have reported that Chiari I malformation or syringomyelia could be treated with instituting control of the CSF circulation [2,7,9].

Modern science and technology could suggest using cellular and tissue therapies for the treatment of hydrocephalus. By using tissue engineering techniques, transplantation of the cells or tissue that have a great capacity for water absorption into the subrarachnoid space or under the scalp with a connection to the ventricle could relieve hydrocephalus [6]. This new treatment method should be explored as another alternative for treating hydrocephalus.

The VP shunting relieved the ventricular dilation of this dog that suffered with hydrocephalus and that presented for ataxia, yet the Chiari I malformation and syringomyelia remained. VP shunts are most commonly used in small animals and a successful outcome may be more likely in the animals that display minimal clinical signs and symptoms [10].

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Lateral radiography reveals a mildly enlarged skull, an open fontanelle and a partial protrusion on the occipital bone.

Fig. 2

T1-weighed transverse (A) and T2-weighed sagittal (B) MRI scans, demonstrating asymmetrically enlarged lateral ventricles, slight dilation of the third ventricle, syringomyelia in the region of C2, 3, 4 (B, arrowhead) and caudal (foramen magnum) descent of the cerebellum (Chiari I malformation) (B, arrow).

References

1. Bagley RS. Slatter D, editor. Intracranial surgery. Textbook of Small Animal Surgery. 2003. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders;1261–1277.

2. Eule JM, Erickson MA, O'Brien MF, Handler M. Chiari I malformation associated with syringomyelia and scoliosis: a twenty-year review of surgical nonsurgical treatment in a pediatric population. Spine. 2002. 27:1451–1455.

3. Fenner WR. Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, editors. Diseases of the brain. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 1995. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders;578–629.

4. Harrington ML, Bagley RS, Moore MP. Hydrocephalus. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1996. 26:843–856.

5. Hoppe-Hirsch E, Sainte RC, Renier D, Hirsch JF. Pericerebral collections after shunting. Childs Nerv Syst. 1987. 3:97–102.

7. Kitagawa M, Kanayama K, Sakai T. Subdural accumulation of fluid in a dog after the insertion of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Vet Rec. 2005. 156:206–208.

8. Klekamap J. The pathophysiology of syringomyelia-historical overview and current concept. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2002. 144:649–664.

9. Milhorat TH, Chou MW, Trinidad EM, Kula RW, Mandell M, Wolpert C, Speer MC. Chiari I malformation redefined: clinical and radiographic findings for 364 symptomatic patients. Neurosurgery. 1999. 44:1005–1017.

10. Platt SR, Olby NJ. BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Neurology. 2004. 3rd ed. Gloucester: British Small Animal Veterinary Association;120–123.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download