Abstract

An 8-month old intact male Turkish Angora cat was referred to the Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital (VMTH), Seoul National University, for an evaluation of anorexia and severe dyspnea. The thoracic radiographs revealed significant pleural effusion. A cytology evaluation of the pleural fluid strongly suggested a lymphoma containing variable sized lymphocytes with frequent mitotic figures and prominent nucleoli. The feline leukemia virus and feline immunodeficiency virus tests were negative. The cat was euthanized at his owner's request and a necropsy was performed. A mass was detected on the mediastinum and lung lobes. A histopathology evaluation confirmed the mass to be a lymphoma. Immunohistochemistry revealed the mass to be CD3 positive. In conclusion, the cat was diagnosed as a T-cell mediastinal lymphoma.

Mediastinal lymphoma is most often presents as being the characteristic form of the disease in cats. [1]. The mediastinal form involves the thymus, mediastinal, and sternal lymph nodes. Prior to 1980, this disease was reported to be a common type of lymphoma, accounting for 20 to 40% of cases in the United States [6], 10 to 50% of cases in the United Kingdom [3,6], and 70% of cases in Japan [9]. However, recent studies have found a much lower prevalence for feline mediastinal lymphoma; <15% of cases in the United States [10] and approximately 25% of cases in Australia. [2,5] Previous studies reported that 73% of cats with mediastinal lymphoma test positive to the feline leukemia virus (FeLV) [10]. In addition, it was reported that young cats have a predisposition to the disease [2,9]. However, some reports showed a decreasing prevalence of FeLV infections in cats with a lymphoma while there has been an increasing incidence of feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) infections, which significantly increases the risk of developing a lymphoma [8]. The majority of the immunophenotypes of mediastinal lymphoma in cats are the T-cell lineage [4,6,10].

Although mediastinal lymphoma is a common neoplasm in young cats, there is no data showing a clinical case of mediastinal lymphoma in Korea. This report describes a case of FeLV negative lymphoma in a young cat.

An 8-month-old male Turkish Angora cat was referred to the Seoul National University Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital with severe dyspnea, depression and anorexia. The cat was severely depressed and showed open-mouth breathing as well as muffled heart sounds.

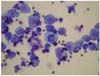

A radiographic examination of the chest revealed increased radiopacity in the cranial portion of the thorax. A bilateral distracted caudal lung lobe with severe bilateral pleural effusion was detected (Fig.1). The initial laboratory tests included a complete blood cell count (CBC) and a serum chemistry panel. There were no abnormal CBC counts (white blood cell 9,000/µl; hemoglobin 12.4 g/dl; hematocrit 38%; serum calcium 10.1 mg/dl). The FeLV (FAST Test FeLV; MegaCor Diagnostic, Austria) and the FIV (AGEN Biomedical, Australia) tests were negative. Thoracocentesis was performed immediately for a cytology examination as well as to relieve the clinical signs. The pleural effusion was evaluated as follows; total nucleated cell counts, 42,600/ml; total protein, 4.6 g/dl; and pH 7.5. The cytology characteristics of the cells in the pleural effusion showed frequent mitotic figures, one or two large nucleoli and variable sized lymphocytes. The other characteristics were a scant amount of highly basophilic cytoplasm and infrequent cytoplasmic vaccuolation. From these findings, the cat was tentatively diagnosed with mediastinal lymphoma (Fig. 1). The treatment was started initially with furosemide 4 mg/kg IV and repeated thoracocentesis to improve the dyspnea caused by the pleural effusions. The cat was hospitalized in the intensive care unit, given IV fluids at half of the maintenance rate (lactated Ringer's solution with 20 mEq/l of potassium chloride), with oxygen being given all day. After two days treatment, the cat's signs of dyspnea were alleviated and its appetite was recovering slowly.

Further examinations, such as bone marrow examination were recommended but the owner declined this procedure and discharged the cat. Six days after discharge, the cat was returned with severe respiratory distress and euthanized at the owner's request.

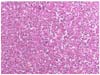

The necropsy showed the anterior mediastinal area to be fully occupied by a homogeneous soft to firm tan mass. The heart was also incarcerated in the mass. A small to large volume of clear fluid was observed in the pleural cavity and pericardial sac (Fig. 2).

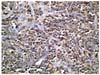

Microscopically, both the anterior mediastinum and pericardial mass were examined and showed similar changes. The masses consisted of monomorphic neoplastic lymphoid cells. The neoplastic cells contained round hyperchromatic nuclei and a small amount of basophilic to amphophilic cytoplasm. Multiple foci of metastases were noted in the lung (Fig. 3).

Immunohistochemically, the neoplastic cells were positive to CD3 (Fig. 4) but negative to CD79. Based on the gross changes, microscopy and immunohistochemistry, the cat was finally diagnosed with mediastinal lymphoblastic lymphoma of a T-cell origin.

Most young cats with a lymphoma have a T-cell lymphoma, while older cats often have a B cell lymphoma [1]. The recent use of monoclonal antibodies has confirmed that 50% to 85% of mediastinal lymphoma are T-cell derived and are significantly more likely to be of this phenotype than the general population of lymphomas.

This paper reports the first case of non-retroviral-associated mediastinal lymphoma in a young cat in Korea.

Despite the rapid decrease in the incidence of FeLV infections, there is a growing prevalence of lymphoma in cats. The incidence of viral-negative lymphoma has almost doubled. The underlying cause of non-retroviral-induced feline lymphoma is unclear. Some links are believed to exist, such as chronic exposure to cigarette smoke, and a relationship between the breed and the development of feline lymphoma [7]. Some studies suggest that Siamese and Siamese-related breeds have a much higher risk of developing lymphoma [5,7]. The breed specificity, the absence of retroviruses, the early onset (mostly under 2 years of age), and consistent clinical presentation suggest a heritable form of lymphoma in Siamese-type breeds. The Turkish Angora cat descended from the Oriental Longhair, and was re-created by breeders using some Oriental breeds such as Javanese or Mandarin. Therefore, it might be related to the Siamese-related breeds or their crosses. Further studies based on a larger number of cases with mediastinal lymphoma in Turkish Angora cats will be needed to determine if this breed has a predisposition to this disease.

Mediastinal lymphoma should be considered in young cats showing respiratory signs. Mediastinal masses may be suspected basis on the physical, radiographic findings. In this case, cytological analysis of the pleural fluid was an important factor in identifying underlying disease. In future, there is a plan to exclude FeLV more aggressively using virus detection techniques such as polymerase chain reaction or immunofluorescent antibody.

In conclusion, T-cell mediastinal lymphoma with a metastasis to the lung is a distinctive case in young cats. Combined with the negative FeLV test, this case reflects the decreasing incidence of FeLV positive lymphoma in young cats.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Cytologic smear of pleural effusion of the cat. Note the neoplastic large lymphocytes with the diameter of nuclei more than 3 times that of RBC and a large central nucleolus. There is one mitotic figure in the center. Wright stain, ×100.

Fig. 2

Gross lesion of the large mass from thorax necropsy of a cat diagnosed mediastinal lymphoma. Note the abnormal large mass around the heart instead of normal lung structures.

References

1. Antony SM, Gregory KO. Gregory KO, Antony SM, editors. Lymphoma. Feline Oncology. 2001. Trenton, Jackson: Veterinary Learning Systems;191–219.

2. Court EA, Watson AD, Peaston AE. Retrospective study of 60 cases of feline lymphosarcoma. Aust Vet J. 1997. 75:424–427.

3. Crighton GW. Clinical aspects of lymphosarcoma in the cat. Vet Rec. 1968. 83:122–126.

4. Gabor LJ, Canfield PJ, Malik R. Immunophenotypical and histological characterization of 109 cases of feline lymphosarcoma. Aust Vet J. 1999. 77:436–441.

5. Gabor LJ, Marlik R, Canfield PJ. Clinical and anatomical features of lymphosarcoma in 118 cats. Aust Vet J. 1998. 76:725–732.

6. Gruffydd-Jones TJ, Gaskell CJ, Gibbs C. Clinical and radiological features of anterior mediastinal lymphosarcoma in the cat: a review of 30 cases. Vet Rec. 1979. 104:304–307.

7. Louwerens M, London CA, Pederson NC, Lyons LA. Feline lymphoma in the post-feline leukemia virus era. J Vet Intern Med. 2005. 19:329–335.

8. Peaston AE, Maddison JE. Efficacy of doxorubicin as an induction agent for cats with lymphosarcoma. Aust Vet J. 1999. 77:442–444.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download