Abstract

Streptococcus suis is regarded as one of the major pathogens of pigs, and Streptococcus suis type 2 (SS2) is considered a zoonotic bacterium based on its ability to cause meningitis and streptococcal toxic shock-like syndrome in humans. Many bacterial species contain genes encoding serine/threonine protein phosphatases (STPs) responsible for dephosphorylation of their substrates in a single reaction step. This study investigated the role of stp1 in the pathogenesis of SS2. An isogenic stp1 mutant (Δstp1) was constructed from SS2 strain ZJ081101. The Δstp1 mutant exhibited a significant increase in adhesion to HEp-2 and bEnd.3 cells as well as increased survival in RAW264.7 cells, as compared to the parent strain. Increased survival in macrophage cells might be related to resistance to reactive oxygen species since the Δstp1 mutant was more resistant than its parent strain to paraquat-induced oxidative stress. However, compared to parent strain virulence, deletion of stp1 significantly attenuated virulence of SS2 in mice, as shown by the nearly double lethal dose 50 value and the lower bacterial load in organs and blood in the murine model. We conclude that Stp1 has an essential role in SS2 virulence.

Streptococcus suis type 2 (SS2), which causes septicemia, meningoencephalitis, and arthritis, is an important pathogen of pigs and humans [15]. Strains with high pathogenicity can even cause toxic shock syndrome in humans [10]. Incidence of SS2-related diseases in humans working with pigs is increasing around the world [12]. The bacterium enters the swine host through the respiratory tract and after colonization in the tonsils reaches the central nervous system via blood circulation, leading to fatal septicemia or meningoencephalitis [35]. Considerable progress has been made in recent years in deciphering the SS2 virulence factors, such as muramidase-releasing protein, suilysin, s-ribosylhomocysteinase, SalK/SsalR (a two-component system of the 89K PAI) and CovR (orphan response regulator) [410]. The results of such studies have led to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of SS2.

Regulation of protein function or enzyme activity by reversible phosphorylation is important for maintenance of cellular responses to dynamic internal or external environmental conditions in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes [26]. Serine/threonine protein phosphatases (STPs) dephosphorylate their substrate proteins in a single reaction step [24]. The STPs are divided into two large families, the phosphoprotein phosphatase P (PPP; PP1, PP2A, and PP2B) and the phosphoprotein phosphatase M family (PPM; PP2C), on the bases of sequence similarity, metal ion dependency, and inhibitor sensitivity [28]. Based on sequence similarities, Streptococcus (S.) suis STP belongs to the PP2C subfamily of the PPM [3].

Studies on prokaryotic STPs have increased in number in recent years. The STP secreted from S. pyogenes is apoptotic in HEp-2 cells [1]. Mycoplasma genitalium expresses STP critical for its virulence [21]. In Staphylococcus aureus, STP1 contributes to reduced virulence and susceptibility to vancomycin [7]. Stp1 of group B Streptococcus mediates post-transcriptional regulation of hemolysin, autolysis, and virulence [24]. A Streptococcus suis serotype 9 (SS9) strain contains stp gene that was involved in virulence [37]. There are two STPs in SS2 (encoded by stp1 and stp2) that belong to the PPM and PPP families, respectively [25]. Homology of the amino acid sequences of stp1 between SS9 and SS2 is 99.0%, while it is 23.1% between SS9 stp1 and SS2 stp2. Functions of STP in SS2 infection remain unreported to date. This study examined whether Stp1 of SS2 is a virulence factor by testing the effects of a stp1 deletion mutant in cultured cells and mice.

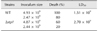

The strains of S. suis and Escherichia (E.) coli used for cloning and mutant construction are listed in Table 1. The SS2 strain ZJ081101 was isolated from the lungs of a diseased pig. Brain heart infusion (BHI; Oxoid, UK) was used for culturing S. suis at 37℃, while Luria-Bertani broth or Luria-Bertani agar was used for culturing E. coli. For cloning and the selection of mutants, the following antibiotics (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were mixed with the culture media: spectinomycin at 100 mg/mL for SS2 and 50 mg/mL for E. coli; chloramphenicol at 4 mg/mL for SS2 and 8 mg/mL for E. coli; and ampicillin at 100 mg/mL for E. coli.

To construct the stp1 deletion mutant from SS2 strain ZJ081101, the 5- and 3-flanking regions of stp1 were PCR-amplified with primer pairs L1/L2 and R1/R2 carrying SphI/SalI and BamHI/EcoRI restriction sites, respectively (Table 2). The cat gene (from pSET6s) was inserted at the SalI/BamHI sites to generate a gene cassette that was then transferred to the temperature-sensitive shuttle vector pSET4s after digestion by corresponding restriction enzymes to generate the stp1-knockout vector pSET4s-Δstp1 (panel A in Fig. 1). Procedures for selection of mutants by allelic exchange via double crossover have been described previously [3031]. The resulting Δstp1 mutant strain was verified by polymerase chain reation (PCR) amplification with primers In1/In2, Cat1/Cat2, Out1/Cat2, and Cat1/Out2 and confirmed by DNA sequencing [37].

This was carried out essentially as described by Neiss et al. [22]. Briefly, the bacterial cells were subjected to fixation in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and treatment with 1% OsO4 in phosphate buffer, each followed by washing. Specimens were then dehydrated by a graded series of ethanol [29] from 30% to 100% and transferred to absolute acetone for 20 min. Specimens were then placed at room temperature in a mixture of absolute acetone and resin at a 1:1 ratio for 1 h, transferred to a 1:3 ratio of absolute acetone to resin mixture for 3 h, and to a Spurr's resin mixture for overnight. Before thin sectioning, specimens were embedded in capsules containing the embedding medium and heated at 70℃ for approximately 9 h. The bacterial sections were stained by uranyl acetate and alkaline lead citrate, each for 15 min, and inspected via transmission electron microscopy (Model H-7650; Hitachi, Japan).

The ORF of stp1 was amplified from the genome DNA of SS2 strain ZJ081101 by PCR with the primer pairs ES1-Stp1/ES2-Stp1 (Table 2). The verified complete gene was cloned, using the EcoR I and Bgl II sites, into pET-32a (Invitrogen, USA) which contains a 22 kDa His-tag-encoding sequence. The recombinant plasmid pET-Stp1 was transformed into E. coli Rosetta (DE3) for expression of the recombinant Stp1 (rStp1). E. coli pET-Stp1 cells in their log phase of growth were induced with 1 mmol/L of isopropyl-β-D–thiogalactopyranoside at 37℃ for 4 h. The rStp1 protein was purified by Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity chromatography and concentrated by ultrafiltration (Millipore, USA). The filtrates were passed through a 0.22-µm membrane (Millipore) and held at −80℃ until use.

p-Nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) was used as a substrate as described [16] in 500 µL of phosphatase buffer [50 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.0), and 2 mM MnCl2] containing 20 mM pNPP and 2 µg of Stp1. Hydrolysis of pNPP in the samples was measured after incubation for 10 min by determining the increase in absorbance of p-nitrophenol (pNP) at 405 nm (SpectraMax M2; Molecular Devices, USA).

The SS2 strains, both wild-type and mutant, were incubated at 37℃ for 6 to 7 h and used to prepare cytoplasmic and cell-wall proteins from whole bacterial cells for SDS-PAGE and western blotting. Whole bacterial lysates were prepared by treating the bacterial suspensions in a Precellys 24 homogenizer (Bertin Instruments, France) in the presence of 0.1 mm ceramic beads at 3,360 × g repeated 5 times for 30 sec each. The supernatant samples were collected as whole cell cytoplasmic proteins (CPP) after centrifugation and saved at −80℃. The precipitates were the cell-wall proteins (CWP) remaining after treatment with 1% Triton-100 in 50 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

The Bradford method was used to quantify the concentrations of the protein samples. Thirty micrograms of each protein sample were subjected to SDS-PAGE on 12% gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore). The membranes were blocked with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% non-fat milk and subjected to probing with the antiserum to rStp1 or rGAPDH and to HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG [Multisciences (Lianke) Biotech, China]. Chemiluminescence substrate (SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate; Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was used to visualize the protein bands.

The mutant strain Δstp1 and its parent strain were grown in BHI containing gradient concentrations of H2O2 or paraquat (a chemical generator of superoxide anions) [6] and incubated at 37℃. The cultures were examined at 620 nm after 4 and 8 h of incubation on SpectraMax M2 microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

Adhesion of the Δstp1 mutant and its parent strain to murine endothelial cell line bEnd.3 and human epithelial cell line HEp-2 was determined as previously described [17]. Bacterial cultures at the mid-log phase (107 CFU/well; CFU, colony-forming unit) were added to the cells in 24-well culture plates at 100 multiplicity of infection (MOI). The plates were spun at 800 × g for 10 min and subjected to incubation for 1 h incubation at 37℃ and 5% CO2. The infected cells were washed with PBS and disrupted by repeated pipetting with sterile distilled water. The cell lysates were transferred to Eppendorf tubes and vortexed to release the bacteria. The samples were then 10-fold diluted in PBS and plated on BHI agar plates for bacterial counting. Adhesion (%) was defined as (CFUAdh/CFUTotal) × 100 [33].

The murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 was used to examine the effect of stp1 deletion on phagocytosis and intracellular survival according to a previously reported protocol [8]. Briefly, the cells were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco, USA) in 24-well plates. Wild-type and mutant SS2 strains were incubated in BHI broth for 6 h at 37℃, pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended in sterile PBS. The cells were infected for 30 min at 37℃ at 100 MOI, washed, and incubated for 1 h in fresh RPMI 1640 medium containing gentamicin (100 mg/mL) and penicillin G (5 mg/mL) to inactivate extracellular bacteria. Cells were then washed and incubated in the fresh medium containing 20 mg/mL of gentamicin. The cells were subjected to further incubation at 37℃ and 5% CO2 for 1 or 2 h. After incubation, the cells were trypsinized and disrupted by repeated pipetting for bacterial enumeration on BHI agar plates. Survival (%) was calculated as CFU2h/CFU1h × 100.

BALB/c mice were used in experimental infections to evaluate the role of stp1 in SS2 virulence [36]. For determination of lethal dose 50 (LD50), eleven groups of 4-week-old female BALB/c mice (10 per group) were randomly allocated. Five groups were assigned to each strain (wild-type or its mutant Δstp1), and the last group of each strain received PBS as a sham control treatment. Five gradient inoculum sizes were used for intraperitoneal infection. Mortality was recorded twice a day for 7 days post-infection. The improved Karber's method was used to calculate LD50. The bacterial burdens in blood and organs were examined in mice receiving intraperitoneal inoculation of the wild-type strain or its mutant (10 mice per strain) at 6.0–8.0 × 108 CFU/mouse. Mice were euthanized at 24 and 48 h post-infection (hpi), and their brain, kidney, liver, and spleen were removed and homogenized individually in 1 mL PBS at pH 7.4. The homogenates were 10-fold diluted in PBS and appropriate dilutions were plated onto BHI agar plates. Anti-coagulant blood samples (100 µL) were collected at 24 and 48 hpi. Animal experiments were conducted following the guidelines and approved protocols of the Laboratory Animal Management Committee of Zhejiang University (approval No.2015029).

A stp1 knockout mutant was produced by electrotransforming suicide vector pSET4s containing a CatR cassette (panel A in Fig. 1) into wild-type competent SS2 cells and was used to evaluate the role of stp1 in pathogenesis. The SS2 Δstp1 mutant was generated by allelic change of stp1 with cat, which was verified by sequencing of the PCR product. Null expression of Stp1 in the mutant was confirmed by absence of its band on the western blot probed with anti-Stp1 polyclonal antibody. The results confirmed successful inactivation of stp1 in the SS2 strain (Fig. 1).

To determine whether Stp1 of SS2 is a functional phosphatase, we expressed Stp1 in E. coli. The results showed that rStp1 was successfully expressed as a 41 kDa His-tagged fusion protein. Hydrolysis of pNPP was measured by assessing an increase in absorbance of pNP at 405 nm over 10 min. We observed that rStp1 hydrolyzed pNPP in the presence of Mn2+ (Fig. 3).

The bEnd.3 and HEp-2 cell lines were used to determine the effects of stp1 deletion on adhesion of SS2 to host cells. Fig. 4 shows that the Δstp1 mutant exhibited better adhesion to both cell lines than that of its parent strain: 1.92 ± 0.07 vs. 0.30 ± 0.014 (p < 0.01) in bEnd.3 cells and 1.92 ± 0.86 vs. 0.40 ± 0.047 (p < 0.05) in HEp-2 cells.

Fig. 5 shows that there was no marked difference in phagocytosis between Δstp1 mutant and its parent strain. However, the mutant was more resistant than the wild-type strain to killing by macrophages (0.79 ± 0.08 vs. 0.16 ± 0.037, p < 0.05). By using the chemical peroxides H2O2 or paraquat in BHI broth, we observed that the Δstp1 mutant was more resistant than its parent strain to paraquat treatment at 5 to 10 mM (p < 0.01), but not to hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 6). These results suggest that deletion of stp1 enhanced resistance to phagocytic killing, probably by increasing the resistance to reactive oxygen species (ROS).

The role of SS2-stp1 in virulence to BALB/c mice was examined by assessing responses to inoculation of 2.44–2.47 × 109 CFU of the relevant strains per mouse. Death rate was 80% for mice challenged with the wild-type strain and 20% when Δstp1 mutant-challenged. At day 5 post-infection, doubling the inoculum level led to 100% death (10/10) in mice receiving the wild-type strain, but only 60% (6/10) death in mice inoculated with the Δstp1 mutant. Compared to its parent strain, deletion of stp1 decreased the virulence of SS2 (LD50: 2.7 × 109 CFU for Δstp1 strain vs. 1.51 × 109 CFU for parent strain; Table 3). Bacterial burdens in blood and internal organs were lower in the Δstp1 mutant than in its parent strain. At 48 hpi, bacterial load in organs of mice receiving the parent strain remained high, while the load at 48 hpi in mice inoculated with Δstp1 mutant was below the detection limit (2 log, i.e., 100 CFU) of the method used (Fig. 7). These findings indicate that inactivation

of stp1 reduces virulence of SS2 in mice.

In pigs and humans in Europe and Asia, SS2 is the serotype most frequently associated with disease [13]. A recent review indicated that there are more than 60 bacterial components that have been identified in relation to SS2 virulence, including surface and secreted factors, proteinases/enzymes, and transcriptional regulators [10]. Bacteria adapt to changing environments by regulating their gene expression through signal transduction systems. In SS2, SalK/SalR [20], IhK/Irr [19], and an orphan response regulator CiaRH [14] were reported to contribute to its virulence. Early reports have indicated that STPs have important roles in bacterial physiology, cell division, and growth by modulating phosphorylation states of their partner kinases (the serine/threonine kinases) or other substrates important in metabolism or virulence [3112334]. Herein, we present evidence that Stp1 of SS2 has phosphatase activity and is a virulence factor in a mouse model.

A S. suis infection starts by colonizing the nasopharyngeal tissue. Bacterial interaction with the epithelial cells in the respiratory tract is central to the initiation of infection and in further spread from the respiratory tract to the bloodstream [9]. Once in the bloodstream, phagocytic cells have a pivotal role against the invading pathogens. In this study, we reveal that deletion of stp1 enhances adhesion of SS2 to both the HEp-2 and bEnd.3 cell lines, suggesting that Stp1 might suppress the adhesiveness of SS2 to host cells. This may indicate that Stp1 has a negative regulatory effect on expression of adhesins on the bacterial surface. Since the Δstp1 mutant exhibited increased survival in macrophages, we suspect that this might be due to an increased resistance to ROS. In the paraquat-induced superoxide radical (O2−) system, the stp1 deletion mutant was more resistant than its parent strain. We propose that this might be related to regulation of SodA (a superoxide dismutase) by Stp1, which is capable of protecting SS2 from damage by ROS [32]. In Listeria monocytogenes, a superoxide dismutase is post-translationally controlled by phosphorylation of its STP [2].

Theoretically, enhanced resistance to macrophage killing as well as increased adhesion of the stp1 deletion mutant would lead to increased virulence. However, we found that the virulence of the Δstp1 mutant was in fact attenuated in mice, as shown by the high LD50 value as well as the reduced bacterial burden in internal organs and blood. This indicates that phenotypic changes in cultured cells in vitro are not correlated with in vivo situations in this particular phosphatase Stp1. This could be due to multiplicity of target protein substrates that are regulated post-translationally by Stp1 and to changes in several functions other than adhesion and phagocytic killing. In prokaryotes, there are fewer STP than serine/threonine kinases, indicating that STPs have multiple substrates [18]. In S. agalactiae, deletion of stk1 or double deletion of stp-stk1 has resulted in virulence attenuation [26]. However, the role of stp1 on the virulence of S. agalactiae remains undescribed [27]. The stp deletion mutant of S. aureus N315 exhibited increased resistance to antimicrobials, but it was not evaluated for its role in virulence [5].

Taken together, our data show for the first time that stp1 is important in the virulence of SS2. Further studies are needed to analyze the dephosphorylation profiles of its potential substrates (including SodA) and their relationship to ensuing changes of bacterial functions; thereby resolving the discrepancy between virulence attenuation in mice and the increased adhesion and resistance to macrophage killing in vitro as a result of stp1 deletion.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Construction of the stp1 deletion mutant of Streptococcus suis type 2 and its identification by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). (A) Schematic representation of the allelic exchange of chromosomal stp1 with vector-carried cat between pSET4s-Δstp1 and the chromosome of ZJ081101 by homologous recombination. (B) PCR confirmation of the mutant strain Δstp1. Lane 1, primers gadph and cps2J for Δstp1; Lane 2, gadph and cps2J for ZJ081101; Lanes 3, 5, and 7, primers In1/In2, Cat1/Cat2 and Cat1/Out2 for Δstp1; Lanes 4, 6, and 8, primers In1/In2, Cat1/Cat2 and Cat2/Out1 for ZJ081101; M, Marker DL2000. (C) Stp1 protein is absent in the stp1 mutant as determined by western blotting with anti-Stp1 polyclonal antibody (CPP, cytoplasmic proteins; CWP, cell-wall proteins).

Fig. 2

Cell morphology of Streptococcus suis type 2 wild-type (WT) and its isogenic Δstp1 mutant. Transmission electron micrographs of bacteria (A–C). Scale bars = 5 µm (A), 0.2 µm, 100 nm, 50 nm (B, from left to right), 0.2 µm, 100 nm, 100 nm (C, from left to right).

Fig. 3

Phosphatase activity of Stp1 of Streptococcus suis type 2. (A) Purification of protein Stp1. (B) Dephosphorylation of p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) with Stp1 in the Mn2+ buffer. (C) Kinetics of pNPP hydrolysis by Stp1 as measured at different substrate concentrations over 10 min. The Km and Vmax were determined to be 5.95 (± 1.265) mM and 1.586 (± 0.09) nmol/µg per min, respectively. OD, optical density.

Fig. 4

Comparison of Streptococcus suis type 2 wild-type (WT) and its isogenic Δstp1 mutant effects on adhesion to bEnd.3 and HEp-2 cell monolayers. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Fig. 5

Comparison of Streptococcus suis type 2 wild-type (WT) and its isogenic Δstp1 mutant effects on phagocytosis and survival in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. **p < 0.01. n.s., no significant difference.

Fig. 6

Resistance of Streptococcus suis type 2 wild-type (WT) and its isogenic Δstp1 mutant in BHI broth containing gradient levels of H2O2 or paraquat incubated at 37℃. The optical density at 620 nm was measured at hours 4 and 8. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. n.s., no significant difference.

Fig. 7

Bacterial load in organs of mice infected with Streptococcus suis type 2 wild-type (WT) and its isogenic Δstp1 mutant. As the lower limit of detection was 100 colony-forming unit (CFU), we did not suggest a null result when no single colony was present in a 10 µL spot of the organ homogenates; in such a case, we assigned an arbitrary value of 50 CFU to that sample.

Acknowledgments

This work is part of research funded by the National Science Foundation of China (Project 31572472) and the Ministry of Agriculture (Project 201303041).

References

1. Agarwal S, Agarwal S, Jin H, Pancholi P, Pancholi V. Serine/threonine phosphatase (SP-STP), secreted from Streptococcus pyogenes, is a pro-apoptotic protein. J Biol Chem. 2012; 287:9147–9167.

2. Archambaud C, Nahori MA, Pizarro-Cerda J, Cossart P, Dussurget O. Control of Listeria superoxide dismutase by phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2006; 281:31812–31822.

3. Barford D, Das AK, Egloff MP. The structure and mechanism of protein phosphatases: insights into catalysis and regulation. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1998; 27:133–164.

4. Baums CG, Valentin-Weigand P. Surface-associated and secreted factors of Streptococcus suis in epidemiology, pathogenesis and vaccine development. Anim Health Res Rev. 2009; 10:65–83.

5. Burnside K, Lembo A, de Los Reyes M, Iliuk A, BinhTran NT, Connelly JE, Lin WJ, Schmidt BZ, Richardson AR, Fang FC, Tao WA, Rajagopal L. Regulation of hemolysin expression and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus by a serine/threonine kinase and phosphatase. PLoS One. 2010; 5:e11071.

6. Bus JS, Gibson JE. Paraquat: model for oxidant-initiated toxicity. Environ Health Perspect. 1984; 55:37–46.

7. Cameron DR, Ward DV, Kostoulias X, Howden BP, Moellering RC Jr, Eliopoulos GM, Peleg AY. Serine/threonine phosphatase Stp1 contributes to reduced susceptibility to vancomycin and virulence in Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis. 2012; 205:1677–1687.

8. Cybulski RJ Jr, Sanz P, Alem F, Stibitz S, Bull RL, O'Brien AD. Four superoxide dismutases contribute to Bacillus anthracis virulence and provide spores with redundant protection from oxidative stress. Infect Immun. 2009; 77:274–285.

9. Dong W, Ma J, Zhu Y, Zhu J, Yuan L, Wang Y, Xu J, Pan Z, Wu Z, Zhang W, Lu C, Yao H. Virulence genotyping and population analysis of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 isolates from China. Infect Genet Evol. 2015; 36:483–489.

10. Feng Y, Zhang H, Wu Z, Wang S, Cao M, Hu D, Wang C. Streptococcus suis infection: an emerging/reemerging challenge of bacterial infectious diseases? Virulence. 2014; 5:477–497.

11. Gaidenko TA, Kim TJ, Price CW. The PrpC serine-threonine phosphatase and PrkC kinase have opposing physiological roles in stationary-phase Bacillus subtilis cells. J Bacteriol. 2002; 184:6109–6114.

12. Grenier D, Bodet C. Streptococcus suis stimulates ICAM-1 shedding from microvascular endothelial cells. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2008; 54:271–276.

13. Haas B, Vaillancourt K, Bonifait L, Gottschalk M, Grenier D. Hyaluronate lyase activity of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 and modulatory effects of hyaluronic acid on the bacterium's virulence properties. BMC Res Notes. 2015; 8:722.

14. Han H, Liu C, Wang Q, Xuan C, Zheng B, Tang J, Yan J, Zhang J, Li M, Cheng H, Lu G, Gao GF. The two-component system Ihk/Irr contributes to the virulence of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 strain 05ZYH33 through alteration of the bacterial cell metabolism. Microbiology. 2012; 158:1852–1866.

15. Houde M, Gottschalk M, Gagnon F, Van Calsteren MR, Segura M. Streptococcus suis capsular polysaccharide inhibits phagocytosis through destabilization of lipid microdomains and prevents lactosylceramide-dependent recognition. Infect Immun. 2012; 80:506–517.

16. Jin H, Pancholi V. Identification and biochemical characterization of a eukaryotic-type serine/threonine kinase and its cognate phosphatase in Streptococcus pyogenes: their biological functions and substrate identification. J Mol Biol. 2006; 357:1351–1372.

17. Ju CX, Gu HW, Lu CP. Characterization and functional analysis of atl, a novel gene encoding autolysin in Streptococcus suis. J Bacteriol. 2012; 194:1464–1473.

18. Kennelly PJ. Protein kinases and protein phosphatases in prokaryotes: a genomic perspective. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002; 206:1–8.

19. Li J, Tan C, Zhou Y, Fu S, Hu L, Hu J, Chen H, Bei W. The two-component regulatory system CiaRH contributes to the virulence of Streptococcus suis 2. Vet Microbiol. 2011; 148:99–104.

20. Li M, Wang C, Feng Y, Pan X, Cheng G, Wang J, Ge J, Zheng F, Cao M, Dong Y, Liu D, Wang J, Lin Y, Du H, Gao GF, Wang X, Hu F, Tang J. SalK/SalR, a two-component signal transduction system, is essential for full virulence of highly invasive Streptococcus suis serotype 2. PLoS One. 2008; 3:e2080.

21. Martinez MA, Das K, Saikolappan S, Materon LA, Dhandayuthapani S. A serine/threonine phosphatase encoded by MG_207 of Mycoplasm genitalium is critical for its virulence. BMC Microbiol. 2013; 13:44.

22. Neiss WF. Electron staining of the cell surface coat by osmium-low ferrocyanide. Histochemistry. 1984; 80:231–242.

23. Osaki M, Arcondéguy T, Bastide A, Touriol C, Prats H, Trombe MC. The StkP/PhpP signaling couple in Streptococcus pneumoniae: cellular organization and physiological characterization. J Bacteriol. 2009; 191:4943–4950.

24. Pereira SFF, Goss L, Dworkin J. Eukaryote-like serine/threonine kinases and phosphatases in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2011; 75:192–212.

25. Pullen KE, Ng HL, Sung PY, Good MC, Smith SM, Alber T. An alternate conformation and a third metal in PstP/Ppp, the M. tuberculosis PP2C-family Ser/Thr protein phosphatase. Structure. 2004; 12:1947–1954.

26. Rajagopal L, Clancy A, Rubens CE. A eukaryotic type serine/threonine kinase and phosphatase in Streptococcus agalactiae reversibly phosphorylate an inorganic pyrophosphatase and affect growth, cell segregation, and virulence. J Biol Chem. 2003; 278:14429–14441.

27. Rajagopal L, Vo A, Silvestroni A, Rubens CE. Regulation of purine biosynthesis by a eukaryotic-type kinase in Streptococcus agalactiae. Mol Microbiol. 2005; 56:1329–1346.

28. Rajala RVS, Kanan Y, Anderson RE. Photoreceptor neuroprotection: regulation of Akt activation through serine/threonine phosphatases, PHLPP and PHLPPL. In : Rickman CB, LaVail MM, Anderson RE, Grimm C, Hollyfield J, Ash J, editors. Retinal Degenerative Diseases: Mechanisms and Experimental Thergpy. London: Springer;2016. p. 419–424. (Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Vol. 854).

29. Segura M, Gottschalk M. Streptococcus suis interactions with the murine macrophage cell line J774: adhesion and cytotoxicity. Infect Immun. 2002; 70:4312–4322.

30. Takamatsu D, Osaki M, Sekizaki T. Construction and characterization of Streptococcus suis-Escherichia coli shuttle cloning vectors. Plasmid. 2001; 45:101–113.

31. Takamatsu D, Osaki M, Sekizaki T. Thermosensitive suicide vectors for gene replacement in Streptococcus suis. Plasmid. 2001; 46:140–148.

32. Tang Y, Zhang X, Wu W, Lu Z, Fang W. Inactivation of the sodA gene of Streptococcus suis type 2 encoding superoxide dismutase leads to reduced virulence to mice. Vet Microbiol. 2012; 158:360–366.

33. Tang Y, Zhao H, Wu W, Wu D, Li X, Fang W. Genetic and virulence characterization of Streptococcus suis type 2 isolates from swine in the provinces of Zhejiang and Henan, China. Folia Microbiol (Praha). 2011; 56:541–548.

34. Ulijasz AT, Falk SP, Weisblum B. Phosphorylation of the RitR DNA-binding domain by a Ser-Thr phosphokinase: implications for global gene regulation in the streptococci. Mol Microbiol. 2009; 71:382–390.

35. van Samkar A, Brouwer MC, Schultsz C, van der Ende A, van de Beek D. Streptococcus suis Meningitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015; 9:e0004191.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download