Abstract

Somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) is a cost-effective technique for producing transgenic pigs. However, abnormalities in the cloned pigs might prevent use these animals for clinical applications or disease modeling. In the present study, we generated several cloned pigs. One of the pigs was found to have intrapancreatic ectopic splenic tissue during histopathology analysis although this animal was grossly normal and genetically identical to the other cloned pigs. Ectopic splenic tissue in the pancreas is very rare, especially in animals. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such report for cloned pigs.

Somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) is the most widely used technique for generating transgenic pigs among several methods used to produce transgenic animals. This technique is more efficient and cost-effective for large animal species compared to the pronuclear injection method that is widely performed with rodents [6]. However, various congenital disorders of cloned pigs have been reported [47]. Although most abnormalities observed in cloned animals are also found in animals produced by natural reproduction [5], the high incidence associated with cloning is thought to be problematic, especially for using cells, tissues, or organs from cloned animals in human clinical applications such as xenotransplantation. In the present study, we produced several grossly normal cloned pigs and examined their histology to identify any microscopic abnormalities. Interestingly, we found ectopic splenic tissue within the pancreas from one of the cloned pigs.

To produce the cloned animals, SCNT was performed as described our previous study [3] with slight modification. Briefly, fibroblasts from a white Yucatan miniature pig fetus were isolated and cultured in vitro. A single fibroblast was electrically fused with in vitro matured and enucleated porcine oocytes from ovaries collected from an abattoir. A total of 158 reconstructed embryos were electrically activated to undergo further development and then transferred to the oviducts of two surrogate pigs (conventional Landrace X Yorkshire mixed breed). Pregnancies were diagnosed using ultrasonography. The surrogates produced two and three cloned piglets delivered by caesarian section. A total of three piglets with no gross abnormalities were randomly selected and further evaluated. All the animals used in this study were maintained and treated in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Seoul National University (Korea).

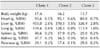

Parentage analysis was performed to confirm genetic identities of the cloned pigs. Genomic DNA was isolated from the donor fibroblasts used for SCNT as well as blood from the cloned pigs and unrelated pigs using a commercial kit (G-Spin Genomic DNA Extraction Kit; iNtRON Biotechnology, Korea). Fluorescently labeled multiplex PCR for 13 markers (SW936, SW951, SW787, S00090, S0026, SW122, SW857, S0005, SW24, SW632, SW72, S0155, and S0255) was performed using a BioTrace Porcine Parentage and Identity Test Kit (Gyeongnam Animal Science and Technology, Korea). Length variations were analyzed using a DNA sequencer (ABI 373; Applied Biosystems, USA) along with GeneScan and Genotyper software (Applied Biosystems). As shown in Table 1, all three of the selected cloned pigs (Clones 1~3) were confirmed as genetically identical.

At 164 days of age, the cloned pigs were euthanized for further analysis. Whole blood was collected from the anterior vena cava of each pig immediately before euthanasia. Blood type, complete blood count, and serum chemistry were then analyzed. As expected, blood antigen phenotypes of all three cloned pigs were identical, and all the animals appeared to be healthy based on the blood analysis results.

For histological analysis, organs (heart, liver, lung, spleen, kidney, and pancreas) from the cloned pigs were collected during necropsy. Weights of the organs from each cloned pig were not identical. However, the organ/body weight ratios were similar (Table 2).

During gross necropsy, a dark brown mass (5 mm × 5 mm) was observed in the pancreatic parenchyma tissue of Clone 1. All tissue samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin wax, sectioned (5 µm-thick), and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The sections were examined microscopically by a certified veterinary pathologist.

Histopathology evaluation did not reveal any significant lesions in any of the tissues examined (data not shown) except for the pancreatic tissue from Clone 1. Splenic tissue was observed in the pancreatic parenchyma of this pig (Fig. 1). The splenic tissue had a framework formed by a mixed capsule of muscular fibers and collagen surrounding the pancreatic tissue. The ectopic spleen consisted of white pulp and red pulp along with a marginal zone that was not clearly delineated. Structural support was provided by connective tissue, the reticulum stroma, traveculae, and the capsule. The white pulp of the ectopic spleen was located around an artery or arteriole, forming lymphoid follicles and periarteriolar lymphatic sheaths. The lymphatic follicles were of various sizes and consisted of lymphocytes with some plasma cells. The periarteriolar lymphatic sheaths were also formed by lymphocytes. Additionally, splenic strings and sheathed capillaries were readily observed in venous sinuses of the red pulp. The boundary between the splenic tissue and pancreas was delineated by a fibrous capsule. However, the boundary was irregular and formed a mixed pattern in some areas. Both splenic and pancreatic tissues were normal in the other two cloned pigs.

Intrapancreatic ectopic splenic tissue is a type of heterotopic tissue remnant. The terms ectopia, choristoma, aberrant rest, or heterotopic and displaced tissue have all been used to describe the microscopic presence of normal tissue in abnormal locations. The origin and development of displaced tissue are still not clear, but may arise from primordial germ cells as they migrate posteriorly in the embryo [2]. Although ectopic splenic tissue is relatively common in human autopsy studies [1], reports of intrapancreatic splenic tissue are extremely rare, especially in animals [8]. In most cases, there is no need to treat intrapancreatic splenic tissues if the animal is asymptomatic. However, ectopic splenic tissues may become symptomatic in some cases due to torsion, spontaneous rupture, hemorrhage, or cyst formation, and must be removed [18].

It should be noted that only one cloned pig had intrapancreatic splenic tissues although all the cloned animals shared the same genetic background. This means that the appearance of ectopic splenic tissue was not caused by genetic differences. However, the present report showed that individual phenotypic differences could be found among cloned animals. In some cases, these differences might be a reason for further experiments or assessment of clinical applications using cloned animals. Clinical criteria for diagnosis for ectopic tissue remnant are still not available, particularly for intrapancreatic splenic tissues. Thus, further studies may be needed to screen for this condition in cloned pigs.

In conclusion, we produced several cloned pigs and confirmed that the animals were genetically identical. Among them, one pig was found to have a histological abnormality, intrapancreatic ectopic splenic tissue, even though the animal was grossly normal. This report showed that ectopic splenic tissue can develop independently from the genetic background and that individual phenotypic differences can occur among genetically identical cloned pigs.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Ectopic splenic tissue in the pancreas of Clone 1. (A) The figure shows splenic tissue widely dispersed at the center of the section. (B) The boundary between the splenic tissue (right area) and pancreas (left area) was delineated by a fibrous capsule. H&E staining, 12.5× (A), 100× (B) magnification.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science and Technology Development (no. PJ009802), Rural Development Administration, Korea; Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE; no. 10048948), Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (IPET; no. 311011-05-3-SB010), the Brain Korea 21 PLUS Program for Creative Veterinary Science Research, and the Research Institute for Veterinary Science. We thank Dr. Jung Bin Lee for performing the microsatellite analysis, Kahee Cho for providing histopathologic analysis; Yoon-Sang Kwon, Ji-Ho Kim, and Hyunil Kim for animal management and sample collection; and Barry Bavister for English editing and providing comments.

References

1. Arkadopoulos N, Athanasopoulos P, Stafyla V, Karakatsanis A, Koutoulidis V, Theodosopoulos T, Karvouni E, Smyrniotis V. Intrapancreatic accessory spleen issues: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. JOP. 2009; 10:400–405.

2. Bundza A, Dukes TW. Some heterotopic tissue remnants in domestic animals. Can Vet J. 1978; 19:322–324.

3. Cho B, Koo OJ, Hwang JI, Kim H, Lee EM, Hurh S, Park SJ, Ro H, Yang J, Surh CD, D'Apice AJ, Lee BC, Ahn C. Generation of soluble human tumor necrosis factor-α receptor 1-Fc transgenic pig. Transplantation. 2011; 92:139–147.

4. Cho SK, Kim JH, Park JY, Choi YJ, Bang JI, Hwang KC, Cho EJ, Sohn SH, Uhm SJ, Koo DB, Lee KK, Kim T, Kim JH. Serial cloning of pigs by somatic cell nuclear transfer: restoration of phenotypic normality during serial cloning. Dev Dyn. 2007; 236:3369–3382.

5. Cibelli JB, Campbell KH, Seidel GE, West MD, Lanza RP. The health profile of cloned animals. Nat Biotechnol. 2002; 20:13–14.

6. Galli C, Perota A, Brunetti D, Lagutina I, Lazzari G, Lucchini F. Genetic engineering including superseding microinjection: new ways to make GM pigs. Xenotransplantation. 2010; 17:397–410.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download