Abstract

We investigated the seroprevalence and risk factors for Brucella seropositivity in cattle in Jordan. The sera from 671 cows were randomly collected from 62 herds. The antibodies against Brucella were detected using a Rose Bengal plate test and indirect ELISA. A structured questionnaire was used to collect information on the cattle herds' health and management. A multiple logistic regression model was constructed to identify the risk factors for Brucella seropositivity. The true prevalence of antibodies against Brucella in individual cows and cattle herds was 6.5% and 23%, respectively. The seroprevalence of brucellosis in cows older than 4 years of age was significantly higher than that in the younger cows. The seroprevalence of brucellosis in cows located in the Mafraq, Zarqa and Ma'an governorates was significantly higher than that of the other studied governorates. The multiple logistic regression model revealed that a larger herd size (odd ratio <OR> = 1.3; 95% CI: 1.1, 2.6) and mixed farming (OR = 2.0; 95% CI: 1.7, 3.7) were risk factors for cattle seropositivity to Brucella antigens. On the other hand, the use of disinfectants (OR = 1.9; 95% CI: 1.1, 2.1) and the presence of adequate veterinary services (OR = 1.6; 95% CI: 1.2, 3.2) were identified as protective factors.

Brucellosis is an infectious bacterial disease that's caused by different species of Brucella. Each Brucella spp. has a preferred natural host that serves as a reservoir [19]. The importance of brucellosis is not exactly known, but this disease can have a considerable impact on human and animal health as well as a socioeconomic impact, and especially in rural areas that largely rely on livestock breeding and dairy products for their livelihood. In developing countries, brucellosis is still considered the most serous and devastating zoonotic disease [2,3,19]. For example, in Jordan, the annual reports of the Ministry of Health (2005) indicated the country has an annual incidence rate of 43.4 cases of brucellosis per 100,000 persons.

Brucellosis is essentially a disease of sexually mature animals with the bacteria having a predilection for placentas, fetal fluids and the testes of male animals [20]. Brucellosis is transmitted by direct or indirect contact with infected animals "often via ingestion and also via venereal routes" [19]. The infection may occur less commonly via the conjunctiva, inhalation and in utero [20]. The most prominent clinical sign of bovine brucellosis is abortion. Other clinical signs are mainly the calving-associated problems and breeding-associated problems such as repeat breeding, a retained placenta and metritis [24]. The infected cows usually abort only once after which a degree of immunity develops and the animals remain infected. At subsequent calvings, the previously infected cows excrete huge numbers of Brucella in the fetal fluids [25].

The epidemiology of Brucella spp. is believed to be complex and it is influenced by several non-technical and technical phenomena [15]. Several researchers have extensively reviewed the factors associated with Brucella infections of animals and they have classified each variable into one of three categories, which are related to the characteristics of the animal populations, the style of management and the biology of the disease [7,11,25]. The factors influencing the epidemiology of brucellosis in cattle in any geographical region can be classified into factors associated with the transmission of the disease among herds and the factors influencing the maintenance and spread of infection within herds [9]. While trying to control or eradicate the infection, it is important to be able to separate these two groups of risk factors. The density of animal populations, the herd size, the type and breed of animal (dairy or beef), the type of husbandry system and other environmental factors are thought to be important determinants of the infection dynamics [22].

The epidemiology of brucellosis in small ruminants and camels has been extensively investigated in Jordan [2-4]. The prevalence of this disease in small ruminants ranges from 27.7% to 45% [2,3], but the prevalence of bovine brucellosis in Jordan is unknown. The objectives of this study were to determine the seroprevalence of bovine brucellosis in Jordan and to elucidate the risk factors associated with the seropositivity for Brucella antigens in cattle.

This cross sectional study was carried out during the period between January, 2007 and June, 2007. The sample size for an infinite population was calculated using C-survey Software 2.0 (UCLA, USA), with an expected prevalence of 10% and a confidence interval of 98%. The resulted sample size (744) was adjusted to the cattle population in Jordan (which is about 75 thousand head). The adjusted sample size (671 cows) was sampled from 62 herds. The number of cows to sample from each governorate depended on the density of cows in that governorate. Herds were randomly selected using the records of the Jordanian Ministry of Agriculture. Cows from each herd were randomly selected using a table of random digits. Only female cows older than 6 months of age were sampled. The herds were stratified into three herd sizes: small herds (≤ 50 cows), medium herds (50-150 cows) and large herds (> 150 cows).

A pre-tested structured questionnaire was administered to each farm owner to collect information on the herd's health and management. The health information included how many cows had disease, the mortality rate, the abortion rate and the vaccination history. The management information included the water source, the cleaning practices, the veterinary services and the workers' farming behaviors. All the farms we studied were dairy cattle farms that did not practice vaccination against brucellosis.

Blood samples were collected from the jugular vein of each selected cow and these were transported to the laboratory on ice. The sera were isolated by centrifugation and stored at -20℃ until testing.

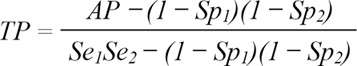

The collected sera were screened for the presence of antibodies against Brucella antigens by using the Rose Bengal plate test "RBPT" and a commercially available indirect enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (iELISA) (JOVAC, Jordan). The Brucella seropositive cows were cows with positive RBPT and ELISA results. According to the manufacturer, the sensitivity and specificity of the RBPT are 89% and 92%, respectively. The ELISA we used had a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 98%. Positive and negative cow sera controls were supplied with the indirect ELISA kit. The resulting prevalence was adjusted to the tests sensitivities and specificities (in parallel) using the following formula [17].

Initially, we conducted a univariate analysis of the different studied variables by using chi-square tests. Variables with p values ≤ 0.05 (two-sided) on the univariable analysis were further tested by performing multivariate logistic regression analysis. To adjust for the clustering effect, a random effect approach was used to construct the logistic model. The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 12 (SPSS, USA).

Out of the 671 tested cattle sera, 68 (10.1%) were positive by both the RBPT and iELISA. When adjusted to the two tests sensitivities and specificities, the true individual seroprevalence of bovine brucellosis in Jordan was 6.5%. Sixteen herds (25.8%) out of the investigated cattle herds had at least one positive cow. The true herd seroprevalence of bovine brucellosis in Jordan was 23%. The seroprevalence of brucellosis in cows older than 4 years of age (59% of the total seropositive cows; 95% CI: 23-69) was significantly higher (p ≤ 0.05) than that in younger cows (the prevalence in cows younger than 4 years and older than 2 years was 8.9%, and the prevalence in cows younger than 2 years was 6.3%). The seroprevalence of brucellosis in cows located in the Mafraq, Zarqa and Ma'an governorates was significantly higher than that reported for the other governorates (Fig. 1). The seroprevalence was 41.5%, 31.4% and 30.7% in Mafraq, Zarqa and Ma'an, respectively. The prevalence of brucellosis in these three governorates was significantly higher than that in the other governorates (χ2 = 31.2, p ≤ 0.05).

The chi-square univariable analysis revealed seven variables with p values ≤ 0.05. Table 1 shows the distribution of the different investigated variables among the Brucella-positive and Brucella-negative cattle herds in Jordan (the data used is that data obtained by the RBPT and ELISA tests in parallel). The multivariable logistic regression model revealed a larger herd size (odd ratio <OR> = 1.3; 95% CI: 1.1, 2.6) and mixed farming (OR = 2.0; 95% CI: 1.7, 3.7) were the risk factors for cattle seropositivity to Brucella antigens. The use of disinfectants (OR = 1.9; 95% CI: 1.1, 2.1) and the presence of adequate veterinary services (OR = 1.6; 95% CI: 1.2, 3.2) were identified as protective factors (Table 2).

This is the first study that has investigated the seroepidemiology of bovine brucellosis in Jordan. The prevalence of bovine brucellosis in Jordan was slightly higher than that reported in Syria [10], Bangladesh [7], Israel [21] and Sri Lanka [25], and it was significantly lower than that reported in Egypt [21], Saudi Arabia [13], Iraq [24] and Zambia [14]. It is worth mentioning that the location of Jordan (in the center of the Middle East) adds more importance for the need to study and understand the epidemiology of trans-boundary diseases such as brucellosis in this country. The epidemiology of brucellosis as well as other trans-boundary diseases in Jordan may indirectly reflect the status of these diseases in the Middle East region.

The prevalence of bovine brucellosis in Mafraq, Ma'an and Zarqa was significantly higher than that reported in the other governorates. Similar observations were reported for small ruminants and camels [2-5]. Those three governorates share long borders with Saudi Arabia, Syria and Iraq, and this is where most of the uncontrolled animal smuggling takes place. In addition, the three governorates are the biggest from the size point of view, and this affect the quality of veterinary services provided to both small ruminant farmers and dairy cattle farmers. Proper border transportation control and vaccination of small ruminants are necessary to bring the prevalence of brucellosis in cattle down to the levels that seen in the other governorates.

Our results suggested that cows older than 4 years of age are more likely to become seropostive to Brucella. A similar observation was made by other researchers [7,8,25]. The high prevalence rate of brucellosis among the older cows might be related to maturity and therefore, the organism propagates and produces either a latent infection or overt clinical manifestations.

In this study, a larger herd size and mixed farming were identified as the risk factors associated with seropositivity to Brucella antigens. Similar observations have been previously reported for other species of animals [1-4,12]. Larger herds provide more chances for contact between the animals. Mixed farming, and especially raising sheep and/or goats along with cattle, was reported by many researchers to be a risk factor for Brucella transmission between different animal species [1,3,18].

The use of disinfectants and the presence of adequate veterinary services were identified as the factors that protect against bovine brucellosis. Similar observations were reported for sheep, goats and camels [2-5]. Proper disposal of aborted materials and highly hygienic procedures are extremely important steps in any successful Brucella control program. It is well known that delivering adequate animal health services results in a low incidence of diseases, and especially those diseases that have an infectious nature. In addition, controlling brucellosis in small ruminants (mainly by Rev-1 vaccination) will indirectly reduce the prevalence of this disease in other animal species, and especially cattle. Poor veterinary service has been identified as a risk factor for brucellosis in Argentina [23] and Mexico [11].

In this investigation, we used two serological assays: the RBPT and indirect ELISA. Buffered Brucella agglutination tests (such as RBPT) are known to have high analytical sensitivity and lower specificity when compared to other serological methods [6]. To overcome the low specificity of the RBPT, we used the indirect ELISA, which is known to have high specificity [16]. Therefore, the resulting percentages were adjusted to the two tests' sensitivities and specificities to reflect the true prevalence of the disease. Moreover, since vaccination against bovine brucellosis is not practiced in Jordan, false seropositivity due to vaccination was absent.

In conclusion, this study is the first to document the importance of bovine brucellosis in Jordan. More attention should be paid towards implementing a proper control program for bovine brucellosis and more efforts should be directed towards improving the animal health delivery system in those governorates that are large in size and share borders with other countries.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Seroprevalence of bovine brucellosis in the different governorates of Jordan. Irbid 12.6%, Jarash 24.3%, Ajloon 15.2%, Mafraq 41.5%, Amman 6.5%, Zarqa 31.4%, Balqa 7.3%, Madaba 23.4%, Karak 1.5%, Tafilah 11.1%, Ma'an 30.7% and Aqaba 0.5% (χ2 = 31.2, p ≤ 0.05). |

Table 1

Distribution of the Brucella seropositive and seronegative cattle herds and the relevance with the different investigated variables

Acknowledgments

This research project was funded by a grant from the Deanship of Research, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan.

References

2. Al-Majali AM. Seroepidemiology of caprine brucellosis in Jordan. Small Rumin Res. 2005. 58:13–18.

3. Al-Majali AM, Majok A, Amarin N, Al-Rawashdeh O. Prevalence of, and risk factors for, brucellosis in Awassi sheep in Southern Jordan. Small Rumin Res. 2007. 73:300–303.

4. Al-Majali AM, Al-Qudah KM, Al-Tarazi YH, Al-Rawashdeh OF. Risk factors associated with camel brucellosis in Jordan. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2008. 40:193–200.

5. Al-Talafhah AH, Lafi SQ, Al-Tarazi Y. Epidemiology of ovine brucellosis in Awassi sheep in Northern Jordan. Prev Vet Med. 2003. 60:297–306.

6. Alton GG, Jones LM, Angus RD, Verger JM. Techniques for the Brucellosis Laboratory. 1988. Paris: Institute National de la Recherche Agronomique.

7. Amin KMR, Rahman MB, Rahman MS, Han JC, Park JH, Chae JS. Prevalence of Brucella antibodies in sera of cows in Bangladesh. J Vet Sci. 2005. 6:223–226.

8. Botha CJ, Williamson CC. A serological survey of bovine brucellosis in four districts of Bophuthatswana. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1989. 60:50.

9. Crawford RP, Huber JD, Adams BS. Nielsen K, Duncan JR, editors. Epidemiology and surveillance. Animal Brucellosis. 1990. CRC Press: Boca Raton;131–151.

10. Darwesh M, Benkirane A. Field investigations of brucellosis in cattle and small ruminants in Syria, 1990-1996. Rev Sci Tech. 2001. 20:769–775.

11. Luna-Martínez JE, Mejía-Terán C. Brucellosis in Mexico: current status and trends. Vet Microbiol. 2002. 90:19–30.

12. McDermott JJ, Arimi SM. Brucellosis in sub-Saharan Africa: epidemiology, control and impact. Vet Microbiol. 2002. 90:111–134.

13. Memish Z. Brucellosis control in Saudi Arabia: prospects and challenges. J Chemother. 2001. 13:Suppl 1. 11–17.

14. Muma JB, Samui KL, Siamudaala VM, Oloya J, Matope G, Omer MK, Munyeme M, Mubita C, Skjerve E. Prevalence of antibodies to Brucella spp. and individual risk factors of infection in traditional cattle, goats and sheep reared in livestock-wildlife interface areas of Zambia. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2006. 38:195–206.

15. Nicoletti P. The epidemiology of bovine brucellosis. Adv Vet Sci Comp Med. 1980. 24:69–98.

17. Noordhuizen JP, Frankena K, van der Hoofd CM, Graat EAM. Application of Quantitative Methods in Veterinary Epidemiology. 1997. Wageningen: Wageningen Pers;76–77.

18. Omer MK, Skjerve E, Holstad G, Woldehiwet Z, Macmillan AP. Prevalence of antibodies to Brucella spp. in cattle, sheep, goats, horses and camels in the State of Eritrea; influence of husbandry systems. Epidemiol Infect. 2000. 125:447–453.

19. Quinn PJ, Carter ME, Markey B, Carter GR. Clinical Veterinary Microbiology. 1994. London: Wolfe Publishing;261–267.

20. Radostits OM, Gay CC, Blood DC, Hinchcliff KW. Veterinary Medicine: A Textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Sheep, Pigs, Goats and Horses. 2000. 9th ed. London: Saunders;867–891.

21. Refai M. Incidence and control of brucellosis in the Near East region. Vet Microbiol. 2002. 90:81–110.

22. Salman MD, Meyer ME. Epidemiology of bovine brucellosis in the Mexicali Valley, Mexico: literature review of disease-associated factors. Am J Vet Res. 1984. 45:1557–1560.

24. Shareef JM. A review of serological investigations of brucellosis among farm animals and humans in northern provinces of Iraq (1974-2004). J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health. 2006. 53:Suppl 1. 38–40.

25. Silva I, Dangolla A, Kulachelvy K. Seroepidemiology of Brucella abortus infection in bovids in Sri Lanka. Prev Vet Med. 2000. 46:51–59.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download