Abstract

Three small breed dogs were referred for the evaluation of neurologic deficits. Upon physical and neurologic examination, all dogs displayed hyperesthesia, pain, and neck stiffness. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed on the brain and spinal cord, and all three dogs presented Chiari-like malformations and syringomyelia. These dogs were treated with prednisolone and furosemide, and showed rapid improvement of clinical signs. Chiari malformations and syringomyelia were not improved because of congenital disorders. This case report demonstrates the clinical and diagnostic features of Chiari-like malformations and syringomyelia in three small breed dogs.

Syringomyelia (SM) of unknown etiology is a condition in which fluid containing cavities develop within the spinal cord parenchyma [9]. Although the cause of SM is unknown, the condition may result from venous obstruction or distension, or may be due to mechanical disruption or shearing of spinal cord tissue planes [9]. Cervical pain is a predominant clinical sign of this disease, which is reported in approximately 80% of affected humans and 35% of affected dogs [7,10], although there is some controversy as to how this disease results in pain. In addition to pain, dogs with SM often scratch at one area of the shoulder, ear, neck or sternum, and may have other neurological deficits such as cervical scoliosis, thoracic limb weakness, and pelvic limb ataxia [6].

Medical treatment can help, but typically does not resolve the clinical signs. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids, gabapentin, and oral opioids can be used for the treatment of SM [10]. The most common procedure performed is foramen magnum decompression, where the hypoplastic occipital bone and sometimes the cranial dorsal laminae of the atlas are removed (with or without a durotomy) to decompress the foramen magnum [1,3].

This case report demonstrates SM/Chiari-like malformation (CM) in three small breed dogs primarily showing hyperesthesia, pain, and neck stiffness based on clinical and diagnostic findings.

Case No. 1: A 6-year-old, spayed female Poodle dog weighing 4.1 kg was presented with neck stiffness, hyperesthesia and hind limb ataxia. Uncoordinated gait of hind limb was acutely presented 3 days ago and had maintained steadily until the admission day. No abnormalities on the complete blood count (CBC) and serum biochemical profile were detected. Neurological examination revealed decreased postural reactions in both hind limbs, though cranial nerves and spinal reflexes were normal. Based on the examination, myelopathy or cerebellar diseases were suspected. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain and spinal cord was obtained using a 0.2 Tesla (E-Scan; Esaote, Italy) in transverse, sagittal, and dorsal, T1- and T2-weighted images. Caudal cerebellar herniation through the foramen magnum and syrinx in the spinal cord between second and fourth cervical vertebrae were noted (Fig. 1).

Based on these findings, the dog was diagnosed with Chiari-like malformations and syringomyelia (CM/SM). The dog was treated with furosemide (Lasix, 2 mg/kg, PO, BID; Handok Pham, Korea) and prednisolone (Prednisolone, 1 mg/kg, PO, BID; Korea Pharma, Korea). The ataxia mildly improved on the third day and completely disappeared by the second week. Medication had been tapered off over 2 months. There was no relapse for 6 months until last follow-ups.

Case No. 2: A 3-year-old, intact male Maltese dog weighing 4.16 kg was presented with the neck pain, stiffness, and weakness in the hindlimbs for 7 days. The owners also reported that the dog had a mild tendency to scratch at its mid-cervical area and was becoming more sensitive. Physical and neurologic examinations revealed cervical pain (including cervical stiffness), shivering, hyperesthesia, bilateral patellar luxation, and tachypnea. CBC, serum biochemistry, and radiography were normal. Brain and spinal MRI scans was performed with 0.2 Tesla unit (E-scan; Esaote, Italy). T1- and T2- weighted images and gadolinium enhanced T1-weighted images were obtained. On T2-weighted images, a hyperintense lesion was found on the pons area and the syrinx formation was more obvious (Fig. 2). Based on the hyperintensity in the pons, an inflammatory status such as granulomatous meningoencephalitis (GME) was also suspected in this case. CM/SM was observed in the midsagittal MRI (Fig. 2).

The dog was treated with furosemide (2 mg/kg, PO, BID), prednisolone (1 mg/kg, PO, BID) for 1 month. Then, prednisolone was continued to taper down for another 4 weeks. After 5 days of treatment, the clinical signs of the dog improved to normal condition. Since then, no side effects or relapses have occurred in over 12 months. We kept 1 mg/kg of prednisolone for 1 month and it continued to taper down for another 4 weeks.

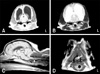

Case No. 3: A 2-year-old, spayed female Yorkshire terrier dog weighing 2.08 kg was presented due to right-sided hemiparalysis with no urination and defecation and cervical pain for 2 days. Upon neurological examinations, right-sided hemiparalysis with episcleral engorgement and delayed pupillary light reflex were observed. Moreover, the dog indicated pain over the cervical area during palpation. Serum biochemistry revealed mildly elevated creatinine kinase (265 U/L; reference range, 10 to 199 U/L). According to the owner's report, the dog was becoming more sensitive around her right cervical area over the past month. In addition, the dog developed hyperesthesia and right-sided limb weakness during that one month. Based on the initial examination, this dog was suspected of having a intracranial disorder. MRI scans of the brain and spinal cord was performed with the same equipment as in cases 1 and 2. Significantly asymmetrical enlargement of lateral ventricles was observed (Figs. 3A and B) and CM/SM was evident on both T1- and T2-weighted images. On the midsagittal MRI of cervical spinal cord, long syrinx formation was evident (Fig. 3C). Serial transverse T1- and T2-weighted images of the spinal cord also showed asymmetrically dilated central canals tilting to the right side (Fig. 3D). CSF evaluation revealed mild neutrophilic pleocytosis and slightly increased protein level (47 mg/dL; reference range: < 25 to 35 mg/dL).

The dog was treated with the same treatment protocol as case No. 2. The symptoms nearly disappeared by the 7 th day of treatment and this dog had a very good response to the treatment. There were no recurring symptoms 10 months after discontinuation of therapy.

The three dogs in this case study were diagnosed with CM/SM. Cervical pain, hyperesthesia, and neck stiffness were the only clinical signs common to all three dogs in this case report. According to the medical history and physical examinations of this case group, it was suspected that the skin over one side of the head, neck, shoulder or sternum might be overly sensitive to touch and the dogs frequently scratch at that area often without making skin contact.

Neuropathic pain can be defined as clinical state of pain accompanied by tissue injury of somatosensory processing in the peripheral or central nervous system, which includes spontaneous pain, paresthesia, dysthesia, allodynia, or hyperpathia [8]. It is hypothesized that the pain-associated behavioral changes of dogs affected by SM are due to neuropathic pain, probably because of injured neural processing in the damaged dorsal horn [7]. The dorsal horn has a key role in the perception of sensory information and transmission to the brain, and sometimes the neural connections and communications through the dorsal horn can be reorganized, resulting in persistent pain states [11].

In this case group, the presence or absence of the signs of probable SM associated pain was recorded. On the midsagittal T1-and T2-weighted MRIs of the three dogs, syrinxes were observed along the cervical spinal cord. Especially, the transverse MR images through the syrinxes explained the right sided asymmetrical region around the dorsal horn in case No. 3. It was thought that injury to the right dorsal horn might cause the right-sided hemiparalysis in case No. 3 due to recent studies [10]. The hyperintense lesion in the pons of case No. 2 may indicate an inflammatory process like GME, which would be an alternative cause of neck pain.

As a possible treatment option, surgical correction is recommended for CM/SM to correct the underlying anatomical or functional abnormality. However, even after an apparently successful procedure resulting in the collapse of the syrinx, the patient may still experience significant pain, especially if the spinal cord dorsal horn was compromised [4,5]. In dogs, surgery appears less successful than in humans because, although there may be a clinical improvement, SM is generally persistent [2,7]. Until a reliable surgical option is defined, pharmaceutical treatment of the clinical signs is likely to be the mainstay of veterinary therapy. Although the three dogs in this case study have had no relapse of the clinical signs after discontinuation of the therapy, long-term monitoring and life-long medical therapy are required because SM is a chronic and intractable condition.

This case report demonstrates that CM/SM is clearly related to neck pain/stiffness and hyperesthesia. Better understanding of the pain symptoms of CM/SM might lead to the possibility of more effective medications and resolutions with dogs suffering from pain of unknown etiology in the veterinary clinics.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

MRI features of the dog in case No. 1. Chiari-like malformation (CM; arrow heads) and syrinx in the spinal cord between second and fourth cervical vertebrae (arrows) were noted on the midsagittal T1- (A) and T2- (B) weighted images. Transverse T1- (C) and T2- (D) weighted images at the level of the third cervical vertebrae revealed syrinx with an enlarged central canal (arrows).

Fig. 2

MRI images of case No. 2. On midsagittal MRIs (A and B), CM (arrow heads) with syrinx formation (arrows), indicating syrinomyelia (SM) is more evident on the T2-weighted image (B). The hyperintense lesion in the pons is also observed on the T2-weighted image (B). Serial transverse MRIs (C and D) reveal the dilation of the central canals (arrows). The dilated central canal is clearer on the T2-weighted image with hyperintensity (D).

Fig. 3

MRI features of case No. 3. Marked asymmetrical dilation of the lateral ventricle is confirmed on T1-(A) and T2-(B) weighted transverse MRIs. CM/SM (arrow) is evident on the midsagittal MRI of the cervical spinal cord (C). Transverse T1-weighted image of the spinal cord also demonstrates an asymmetrically dilated central canal (arrow) tilting to the right side (D).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Korean Research Foundation Grant funded by the Korean Government (KRF-2008-314-E00246).

References

1. Churcher RK, Child G. Chiari 1/syringomyelia complex in a King Charles Spaniel. Aust Vet J. 2000. 78:92–95.

2. Dewey CW, Berg JM, Barone G, Marino DJ, Stefanacci JD. Foramen magnum decompression for treatment of caudal occipital malformation syndrome in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005. 227:1270–1275.

3. Dewey CW, Berg JM, Stefanacci JD, Barone G, Marino DJ. Caudal occipital malformation syndrome in dogs. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet. 2004. 26:886–896.

4. Milhorat TH, Kotzen RM, Mu HT, Capocelli AL Jr, Milhorat RH. Dysesthetic pain in patients with syringomyelia. Neurosurgery. 1996. 38:940–947.

5. Nakamura M, Chiba K, Nishizawa T, Maruiwa H, Matsumoto M, Toyama Y. Retrospective study of surgery-related outcomes in patients with syringomyelia associated with Chiari I malformation: clinical significance of changes in the size and localization of syrinx on pain relief. J Neurosurg. 2004. 100:241–244.

6. Rusbridge C. Neurological diseases of the Cavalier King Charles spaniel. J Small Anim Pract. 2005. 46:265–272.

7. Rusbridge C. Chiari-like malformation with syringomyelia in the Cavalier King Charles spaniel: long-term outcome after surgical management. Vet Surg. 2007. 36:396–405.

8. Rusbridge C, Carruthers H, Dubé MP, Holmes M, Jeffery ND. Syringomyelia in cavalier King Charles spaniels: the relationship between syrinx dimensions and pain. J Small Anim Pract. 2007. 48:432–436.

9. Rusbridge C, Greitz D, Iskandar BJ. Syringomyelia: current concepts in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. J Vet Intern Med. 2006. 20:469–479.

10. Rusbridge C, Jeffery ND. Pathophysiology and treatment of neuropathic pain associated with syringomyelia. Vet J. 2008. 175:164–172.

11. Stanfa LC, Dickenson AH. In vivo electrophysiology of dorsal-horn neurons. Methods Mol Med. 2004. 99:139–153.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download