Abstract

Umbilical hernias in calves commonly present to veterinary clinics, which are normally secondary to failure of the normal closure of the umbilical ring, and which result in the protrusion of abdominal contents into the overlying subcutis. The aim of this study was to compare the suitability of commonly-used herniorrhaphies for the treatment of reducible umbilical hernia in calves. Thirty-four clinical cases presenting to the Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Chittagong Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Chittagong, Bangladesh from July 2004 to July 2007 were subjected to comprehensive study including history, classification of hernias, size of the hernial rings, presence of adhesion with the hernial sacs, postoperative care and follow-up. They were reducible, non-painful and had no evidence of infection present on palpation. The results revealed a gender influence, with the incidence of umbilical hernia being higher in female calves than in males. Out of the 34 clinical cases, 14 were treated by open method of herniorrhaphy and 20 were treated by closed method. Complications of hernia were higher (21%) in open method-treated cases than in closed method-treated cases (5%). Hernia recurred in three calves treated with open herniorrhaphy within 2 weeks of the procedure, with swelling in situ and muscular weakness at the site of operation. Shorter operation time and excellent healing rate (80%) were found in calves treated with closed herniorrhaphy. These findings suggest that the closed herniorrhaphy is better than the commonly-used open method for the correction of reducible umbilical hernia in calves.

A hernia is a protrusion of the contents of a body cavity through a weak spot of the body wall. This may be from accidental or a normal anatomical opening, which does not completely fulfill its physiological function. It is a common defect in calves [11,15,19]. Congenital umbilical hernias are of concern for heritability, although many umbilical hernias are secondary to umbilical sepsis. Multiple births and shortened gestation lengths are two important risk factors for congenital umbilical hernias in calves [7]. These are probably the result of a polygenic threshold character, passively involving a major gene whose expression is mediated by the breed background. Sire and umbilical infections are associated with risk of an umbilical hernia in calves during the first 2 months of life [17]. The frequency of umbilical hernia in the progeny of males ranging from 1-21% is consistent with the hypothesis that enhancer is the carrier of major dominant or co-dominant gene with partial penetrance for umbilical hernia [16]. Hernias may be small at birth and gradually enlarge with age. The contents of an umbilical hernia are usually fat, omentum and, in some larger hernia, segments of small intestines. In cattle, large umbilical hernias are not uncommonly seen with an average frequency of 4-15% [19]. They develop from improper closure of the umbilicus at birth due to the developmental anomaly or hypoplasia of the abdominal muscles or from manual breaking or resection of the cord close to the abdominal wall [18].

Several methods for hernial treatment have been described. Ligation of the hernial sac, use of clamps, suturing of the hernial sac and radical operation are normally performed to correct the umbilical hernia, although open herniorrhaphy is the most common method of veterinary treatment [12]. Despite its common use, open method of herniorrhaphy has many demerits especially bacterial infection that might cause recurrence of hernia. Whether closed herniorrhaphy can minimize these postoperative complications is unclear, although for an irreducible umbilical hernia there is no choice other than open herniorrhaphy. There is no data concerning comparison between the open and closed methods of herniorrhaphy in calves.

The objectives of the present study were to evaluate the outcomes of both closed and open methods of herniorrhaphy used for the treatment of reducible umbilical hernia in bovine calves.

The present study was carried out on 34 clinical cases presenting to the Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Chittagong Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Bangladesh from July 2004 to July 2007. The calves were randomly classified into two groups; group-I (n = 14) and group-II (n = 20), which were treated by open and closed herniorrhaphy, respectively. The ages of the calves ranged from 7 days to 7 months. The histories of the cases indicated that the hernias were noticed at different ages before presentation to the hospital and were almost always observed at 1-2 month of age. Palpable opening in the umbilical region that was > 2 cm was defined as an umbilical hernias. Recording included history of the cases, size of the hernial rings, type of surgical repair of the hernias, presence of adhesions, postoperative care and follow-up of the cases, which were achieved by direct contact phone conversation with the owners.

Food was withheld for 24 h prior to surgery in older calves. Surgical repair was conducted by aseptic preparation of the surgical site of operation after intravenously tranquilizing the fractious animals with Diazepam (Sedil 2%; Square Pharmaceuticals, Bangladesh) at a dose rate of 0.4 mg/kg. Each animal was restrained in the ventro-dorsal position. Circular infiltration anesthesia was done at the umbilical region using 2% lidocaine (Jasocaine; Jayson Pharmaceuticals, Bangladesh) at a dose of 10 mg/kg body weight.

In case of open herniorrhaphy, elliptical skin incisions were made and the adhesions between the parietal peritoneum and skin were freed using both blunt and sharp dissection. The hernial rings were exposed and freshened before their suturing and finally closed by interrupted horizontal mattress sutures mostly with No. 2 chromic catgut (Surgigut; United States Surgical, USA), although the effect of suture materials was not considered in our study. The subcutaneous tissues were then sutured continuously with No. 1-0 chromic catgut and excessive skin was removed for better apposition and finally sutured with No. 2 silk (Johnson & Johnson, India) or nylon (Sutures India, India) in a simple interrupted suture pattern.

In case of closed herniorrhaphy, the hernia contents were pushed-back into the abdominal cavity in a ventro-dorsal position before suturing. It was confirmed that no viscera adhered to the interior of the sac on palpation and no internal umbilical structures were infected at physical examination. Then, a series of interrupted vertical mattress sutures were made using No. 3-4 nylon suture to close the hernial ring from the outside of the skin about 0.5 inch apart from each other. Each animal was treated postoperatively with penicillin-streptomycin at a dose rate of 30,000 IU/kg for the penicillin and 10 mg/kg streptomycin for 5 days (ACME Laboratories, Bangladesh).

All values of hernial distribution related to age, sex, outcome of herniorrhaphy with or without complication and recurrence were reported as a percentage for each group. Fisher's exact test was used for comparisons between groups. Differences between groups were considered as significant whether p < 0.05. Data analysis was performed using SPSS 11.5 software (SPSS, USA).

The age and gender prevalence of umbilical hernia (Fig. 1A) in calves were variable. Female calves showed a higher incidence (24/34, 70.6%) compared to male calves (10/34, 29.4%) (Table 1). Calves < 6 week of age exhibited more umbilical hernias than aged 7 week or more. The highest incidence of umbilical hernias was evident at 5 weeks, whereas the smallest incidence was at < 2 weeks for both males and females.

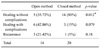

Out of 34 clinical cases, 14 were treated by the open method of herniorrhaphy (group-I, Fig. 1B) and 20 were treated by the closed method (group-II, Fig. 1C). Recurrence rate of hernia in group-I animals was higher (21.42%) than in group-II animals (5%) (Table 2), although the percentages were higher in male calves in both groups. Hernia recurred in three calves treated with open herniorrhaphy within 2 weeks with swelling in situ and muscular weakness at the site of operation. In group-II, recurrence occurred in one calf 1 month later with an abomasal fistula at the site of operation.

Other complications included abscess, inflammatory swelling, accumulation of serous fluid, secondary bacterial infection, which were higher in group-I (42.86%) than in group-II (15%) (Table 2). Healing rate with minimum complications was better in group-II (80%) than in group-I (35.71%) with minimum complications (Table 2), although swelling was totally absent (Fig. 1D) after the open method of surgery. In most cases treated with closed methods of herniorrhaphy, healing was completed within 2 weeks of surgery. The healing was smoother and shorter in duration among young female calves than in older of male calves. Delayed healing was common in male calves in both treatment groups.

The umbilicus in newborn calves consists of the urachus (a tube that attaches the fetal bladder to the placental sac) and the remnants of the umbilical vessels that transport blood between the fetus and its mother. Normally, just after birth these structures shrink until only tiny remnants remain within the abdomen (belly). If the area in the body wall through which these structures passed remains open, abdominal contents can protrude through the defect resulting in an umbilical hernia [1,2]. Hernia size varies depending on the extent of the umbilical defect and the amount of abdominal contents contained within it. Umbilical hernias are the most common birth defects in calves, especially in Holstein-Friesians [9,15,17]. The etiology of umbilical hernias likely has a genetic component [3,8,10,20]; however, excess traction on an oversized fetus or cutting the umbilical cord too close to the abdominal wall are other possible causes. Many umbilical hernias are secondary to umbilical sepsis [17]. They may occur as isolated defects or may be associated with defects of other parts of the body [2]. The prevalence of an open hernial ring in the first week of life can vary between 18-24% depending on the farm sampled [7]. Umbilical hernias are the side effects of genetic pressures for high lactation production or growth rates. The results of the present study indicate that congenital umbilical hernias in calves appear just after birth. The genetic influence on the incidence of congenital umbilical hernia has been suggested in previous studies [7,17]. In addition to heredity, the etiology of an umbilical hernia may be an umbilical infection or abscess [5]. In our study, almost all calves > 1 month old showed a history of umbilical infection early in life. Very similar results were reported in another study, in which sire and umbilical infection were closely associated with umbilical hernia [17]. Umbilical infection may result in weakening of the adjacent abdominal wall and cause an acquired umbilical hernia.

Presently, gender had an effect on the incidence of umbilical hernia. Females showed a higher incidence than males (24 vs. 10, respectively). Similar findings have been reported previously [6,11,14], but are contradictory to other results [7]. The results of open herniorrhaphy were more complicated in the male calves because of the proximity of the penis to the umbilicus, which made it harder to maintain the postoperative bandage than in female calves.

Presently, the incidence of hernia was highest (20.84%) at 5 weeks of age. This may be due to the consequence of the umbilical infection. Nearly identical results were reported in another study, in which umbilical hernia occurred most often at an average age of 6.7 weeks after birth [19].

Various methods have been described in the literature for the treatment of umbilical hernia including counter irritation, clamping, transfixation sutures and even safety pins and commercially-available rubber bands. The most popular technique among them is the wooden or metal clamp technique. This method may result in infection, loss of clamp or premature necrosis of the hernial sac. The latter complication can lead to an open wound, and possibly to evisceration or formation of an enterocutaneous fistula. These methods are suitable only for reducible hernia and not for strangulated or complicated ones [18]. If the hernial ring is more than one finger in size or persists for more than 2 to 3 weeks, than surgical intervention is indicated [13]. Open method of herniorrhaphy is always indicated for older calves when adhesion or abscess is commonly associated with umbilical hernia [9]. Herniorrhaphy can be done by simply closing the abdominal wall with a horizontal mattress pattern of stitches using absorbable or non-absorbable sutures [1,13]. In the current study, the size of the hernial rings was > 1 cm in each case. Herniorrhaphy was carried out using horizontally interrupted stitches with chromic catgut or sometimes sterilized silk for open method, and nylon for the closed method of surgery.

Treatment by closed herniorrhaphy appeared to be a more satisfactory (80%) regimen for reducible umbilical hernia in calves, although a better result was found in the early fixing of hernial rings, consistent with other observations [10]. Ready contact with the floor and licking by the cows may be increase the susceptibility of infection in open herniorrhaphy. The sutures in closed methods of surgery help to promote adhesion by cicatrization between the surface in contact and consequent closure of the hernial orifice.

Although general anesthesia is commonly used in cattle, there are some risks with its use. Local or regional anesthesia is safe and effective, and is still the most desirable procedure in many situations [4]. The present study indicates that local infiltration anaesthesia with or without tranquilization may be quite sufficient for performing the surgical repair. Diazepam (0.4 mg/kg) was used intravenously as a tranquilizer in this study, which was cheap in comparison with xylazine and also produced satisfactory results. Infiltration local anaesthesia with 2% lidocaine was also satisfactory for anaesthesia of the umbilical region. Positioning of the animal on a surgical table was found to be important to facilitate reduction of the hernial contents and herniorrhaphy.

In this study, both the absorbable (catgut) and non-absorbable (silk/nylon) suture materials were used to correct the umbilical hernia. Absorbable sutures were used for comparatively young calves, whereas silk was used with older calves to increase protection. The effects of suture materials and type of hernias were not considered in our study because they have no effect on the outcome of surgical treatment [1]. Better healing and less complication were found in calves treated with the closed method of herniorrhaphy. The results of this study suggest that closed herniorrhaphy may be a suitable and satisfactory choice of surgical treatment for the reducible umbilical hernia in bovine calves.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Umbilical hernia (A) was corrected by both open and closed methods of herniorrhaphy in calf. Horizontal mattress sutures were used to close the hernial ring in open herniorrhaphy (B) after exposing the skin. Vertical mattress sutures were used in closed herniorrhaphy (C) supporting with the quilt. Empty hernial sac was observed after suturing. No swelling (D) was observed after treatment with open method of herniorrhaphy. |

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere thanks to the Dean, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Chittagong Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Chittagong-4202, Bangladesh for providing the necessary facilities to carry out the present study.

References

1. Al-Sobayil FA, Ahmed AF. Surgical treatment for different forms of hernias in sheep and goats. J Vet Sci. 2007. 8:185–191.

2. Dennis SM, Leipold HW. Congenital hernias in sheep. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1968. 152:999–1003.

3. Distl O, Herrmann R, Utz J, Doll K, Rosenberger E. Inheritance of congenital umbilical hernia in German Fleckvieh. J Anim Breed Genet. 2002. 119:264–273.

4. Edmondson MA. Local and regional anesthesia in cattle. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2008. 24:211–226.

5. Gadre KM, Shingatgeri RK, Panchabhai VS. Biometry of umbilical hernia in cross-bred calf (Bos-tarus). Indian Vet J. 1989. 66:989.

6. Hayes HM. Congenital umbilical and inguinal hernias in cattle, horses, swine, dogs and cats: Risk by breed and sex among hospital patients. Am J Vet Res. 1974. 35:839–842.

7. Herrmann R, Utz J, Rosenberger E, Doll K, Distl O. Risk factors for congenital umbilical hernia in German Fleckvieh. Vet J. 2001. 162:233–240.

8. Herrmann R, Utz J, Rosenberger E, Wanke R, Doll K, Distl O. Investigations on occurrence of congenital umbilical hernia in German Fleckvieh. Zuchtungskunde. 2000. 72:258–273.

9. Horney FD, Wallace CE. Jennings PB. Surgery of the bovine digestive tract. Practice of Large Animal Surgery. 1984. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Saunders;493–554.

10. Masakazu S. Umbilical hernia in Japanese black calves: A new treatment technique and its hereditary background. J Live Med. 2005. 507:543–547.

11. Müller W, Schlegel F, Haase H, Haase G. Zum angeborenen Nabelbruch beim kalb. Monatshefte für Veterinärmedizin. 1988. 43:161–163.

12. O'Connor JJ. Dollar's Veterinary Surgery. 1980. 4th ed. London: Bailliere Tindall & Cox;676.

13. Pugh DG. Sheep & Goat Medicine. 2002. Philadelphia: Sounders;104–105.

14. Rieck GW, Finger KH. Untersuchungen zur teratologischen Populationsstatistik und zur Ätiologie der embryonalen Entwicklungsstörungen beim Rind. Gieβener beiträge zur Erbpathologie und Zuchthygiene. 1973. 5:71–138.

15. Rings DM. Umbilical hernias, umbilical abscesses, and urachal fistulas. Surgical considerations. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 1995. 11:137–148.

16. Ron M, Tager-Cohen I, Feldmesser E, Ezra E, Kalay D, Roe B, Seroussi E, Weller JI. Bovine umbilical hernia maps to the centromeric end of bos taurus autosome 8. Anim Genet. 2004. 35:431–437.

17. Steenholdt C, Hernandez J. Risk factors for umbilical hernia in Holstein heifers during the first two months after birth. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004. 224:1487–1490.

18. Turner AS, McIlwraith CW. Techniques in Large Animal Surgery. 1989. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;254.

19. Virtala AMK, Mechor GD, Gröhn YT, Erb HN. The effect of calfhood diseases on growth of female dairy calves during the first 3 months of life in New York State. J Dairy Sci. 1996. 79:1040–1049.

20. Wiesner E, Willer S. Hereditary transmission of congenital umbilical hernia in cattle. Monatshefte für Veterinärmedizin. 1981. 36:790–794.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download