Abstract

Objective

Synchronous occurrence of endometrial and ovarian tumors is uncommon, and they affect less than 10% of women with endometrial or ovarian cancers. The aim of this study is to describe the epidemiological and clinical factors; and survival outcomes of women with these cancers.

Methods

This is a retrospective cohort study in a large tertiary institution in Singapore. The sample consists of women with endometrial and epithelial ovarian cancers followed up over a period of 10 years from 2000 to 2009. The epidemiological and clinical factors include age at diagnosis, histology types, grade and stage of disease.

Results

A total of 75 patients with synchronous ovarian and endometrial cancers were identified. However, only 46 patients met the inclusion criteria. The median follow-up was 74 months. The incidence rate for synchronous cancer is 8.7% of all epithelial ovarian cancers and 4.9% of all endometrial cancers diagnosed over this time frame. Mean age at diagnosis was 47.3 years old. The most common presenting symptom was abnormal uterine bleeding (36.9%) and 73.9% had endometrioid histology for both endometrial and ovarian cancers. The majority of the women (78%) presented were at early stages of 1 and 2. There were 6 (13.6%) cases of recurrence and the 5 year cumulative survival rate was at 84%.

Synchronous primary tumors of the female reproductive organs are relatively rare and it is observed most frequently in endometrial and ovarian cancers. It has been reported that primary cancers of the endometrium and ovary coexist in approximately 10% of all women with ovarian cancer and in 5% of all women with endometrial cancer [1]. The underlying cause and pathogenesis remains unclear though some researchers have postulated that embryologically similar tissues may develop synchronous neoplasms when there is simultaneous exposure to carcinogens or hormonal influences [2,3]. Most of the women present about a decade younger than the median ages of development of endometrial or ovarian cancer alone.

The aim of our study is to look at the clinicopathological characteristics as well as the survival outcome of women diagnosed with synchronous endometrial cancer and epithelial ovarian cancer in Singapore. The focus will be on endometrioid type for uterine cancers.

This was a retrospective cohort study conducted in KK Women's and Children's Hospital, a large tertiary institution in Singapore. The sample consisted of women with synchronous primary endometrial cancer and epithelial ovarian cancers who sought care from the institution, and who were followed up over a period of 10 years from 2000 to 2009. The medical information required was retrieved from the KK Gynaecological Cancer Centre Database as well as the patient records.

The clinico-pathological factors analyzed include the age at diagnosis, presenting symptoms, histology types and stage of disease. The stage of the endometrial and ovarian cancer was based on the FIGO 1988 classification. In our centre, the new FIGO staging (2009) classification was adopted from 2010 onwards hence was not used in this retrospective study. All patients underwent a total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingooophorectomy, bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy and omentectomy. Patients with advanced ovarian cancer were debulked to residual disease less than 1 cm in our centre. All surgical specimens were examined by a pathologist at our institution, according to the criteria described by Scully et al. [4] The pathological criteria for synchronous primary cancers of the endometrium and ovary were as follows: 1) histological dissimilarity of tumors; 2) no or only superficial myometrial invasion of endometrial tumor; 3) no vascular space invasion of endometrial tumor; 4) atypical endometrial hyperplasia additionally present; 5) absence of other evidence of spread of endometrial tumor; 6) ovarian tumor unilateral (80-90% of cases); 7) ovarian tumors located mainly in parenchyma; 8) no vascular space invasion, surface implants, or predominant hilar location in ovary; 9) absence of other evidence of spread of ovarian tumor; and 10) ovary endometriosis present. Patients with non-endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the uterus, borderline and non-epithelial ovarian tumors such as germ cell or sex cord stromal tumors were excluded from this study. Adjuvant treatment such as chemotherapy was given to patients with high risk features or advanced disease. All patients were followed up routinely with physical examination and biochemical markers such as CA-125.

Data analysis was performed using Stata ver. 11.1 (Stata Co., College Station, TX, USA), and survival analysis for follow-up data was adopted and poisson regression was used to derive hazard ratios.

A total of 75 patients with synchronous cancers were identified of which 46 patients met the inclusion criteria. There were 4 patients lost to follow-up. The median follow-up period for the 46 patients was 74.06 months (range, 23.34 to 134.71 months). The incidence rate for synchronous endometrial and ovarian cancer was 8.7% of all epithelial ovarian cancers and 4.9% of all endometrial cancers diagnosed over this time frame.

The median age at diagnosis was 47.3 years ranging from 35.7 to 83.2 years. The cohort consisted of 41 ethnic Chinese (89.1%), 4 Malays (8.7%), and 1 Filipino (2.2%). The most common presenting symptom was abnormal uterine bleeding (e.g., postmenopausal bleeding or irregular menses) and they were found in 17 patients (36.9%). Thirteen patients (28.3%) presented with an abdominal pelvic mass instead. Endometriosis was found in 27 patients (58.7%). The other characteristics are listed in Table 1. Thirty seven patients (80.4%) received adjuvant platinum based chemotherapy and 6 patients (13%) received adjuvant radiotherapy post surgery. Two patients received both adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

The histopathological characteristics of the endometrial cancers are listed in Table 2. We found that 69.6% of patients had grade 1 tumors and 73.9% had FIGO stage I cancer. There was no stage IV endometrial cancer. Myometrial invasion was seen in 52.1% of patients and lymph-vascular space invasion in 30.4% of patients.

The histopathological characteristics of the ovarian cancers are listed in Table 3. We found that 58.7% of patients had FIGO stage I cancers and 47.8% had grade 1 tumors. There was no stage IV ovarian cancer. Endometrioid histology accounted for 73.9% of all cases and the remaining histology types include serous, mucinous, clear cell, undifferentiated and adenosquamous carcinoma.

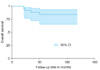

There were 5 (10.9%) deaths, therefore the crude mortality rate was at 11. 14 (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.64 to 26.76) per 103 person months. There were 6 (13.6%) cases of recurrence and the cumulative survival was 84% (95% CI, 70.87 to 97.13).

The difference in mortality rate by age of 50 years was 3.04 (95% CI, 0.27 to 3.23) per 103 person months (p=0.027); by histology, difference in mortality rate was 1.06 (95% CI, -1.92 to 4.03) per 103 person months (p=0.255).

Further analysis of the following risk factors (Table 4), we found that the age >50 years has a hazard ratio of 7.5 (95% CI, 1.21 to 97.19) with a borderline p-value 0.072. Those with dissimilar (endometrioid/non-endometrioid) histology types also appear to have a higher risk of dying (hazard ratio, 1.89) compared to the endometrioid/endometrioid histology group though this did not reach statistical significance (p=0.486). There were no deaths in those with concurrent histological grade 1 ovarian and endometrial tumors or those with concurrent stage I ovarian and endometrial cancers. There were 14 patients with at least one stage III synchronous cancer and there were 5 deaths (35.7%) observed in this group with advanced disease.

Synchronous primary cancer of the uterus and ovary is an uncommon event and this occurs in about 4.9% of all endometrial cancers and 8.7% of all ovarian cancers in our institution. This is similar to that reported by other authors [1,5,6]. On the other hand, ovarian metastases have been reported to occur in about 5% of primary uterine cancers [7], hence it is important to differentiate between the two since it will affect the subsequent treatment as well as the prognosis of affected women. In order to differentiate between the two groups, pathologists have proposed a set of histological criteria to aid in the evaluation of these tumors [4,8]. Methods of molecular analysis such as DNA flow cytometry, loss of heterozygosity on chromosome, X chromosome inactivation, PTEN/MMAC1, beta-catenin, and microsatellite instability have also been developed to help in the differentiation but, to date there is no absolute consensus as to which method is the best [9-14].

Women with synchronous endometrial and ovarian cancer tend to be 10 to 20 years younger than women who suffer from ovarian or uterine cancer alone (predominantly postmenopausal) and the median age reported by various authors range from 41 to 54 years. In our cohort, the median age at diagnosis was 47.3 years. The younger age at diagnosis and multiple site of cancer also brings to question whether there is a possibility of familial cancer syndrome such as Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer, HNPCC). However 2 studies have shown that the prevalence of HNPCC accounts for only 3% and 7% of cases [5,15]. The pathogenesis for synchronous uterine/ovarian cancer is presently unclear. Some authors have suggested that the epithelia of the cervix, uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries and peritoneal surface share molecular receptors (so called secondary Mullerian system) responding to carcinogenic stimulus leading to the development of synchronous primary tumors [16]. However, this can only explain synchronous tumors of similar histology and not dissimilar types.

Several studies have shown that patients with synchronous primary cancers have a good overall prognosis [1,5,6,17,18]. For instance, the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) study found that women with synchronous primary endometrial and ovarian cancers had an overall prognosis of 86% 5 year survival and 80% 10 year survival [1]. The prognosis for our series of patients with synchronous endometrial and ovarian cancers appears to be good as well with a cumulative overall survival of 84% (Fig. 1)

In the analysis of risk factors, we found that age to be an important factor. Those diagnosed below the age of 50 years had a better prognosis than those above 50 years (p=0.027). Similarly, Caldarella et al. [6] also showed that age is an important prognostic factor; the 5 year survival was 94.1% (<50 years) compared to 53.7% (>50 years) (p=0.004).

In our cohort, there was a trend towards better survival for patients with endometrioid/endometrioid tumors versus those with endometrioid/other tumors though it did not reach statistical significance (p=0.255). Similarly, Soliman et al. [5] reported that patients with endometrioid/endometrioid tumors of the uterus and ovary had a better overall survival. Eifel et al. [17] has also reported that patients with endometrioid/endometrioid synchronous tumors had a better overall prognosis when compared to patients with stage II ovarian cancers or stage III endometrial cancers. On the other hand, Caldarella et al. [6] reported that there was no relevant difference survival in their study. Zaino et al. [1] reported that early stage and low histological grade especially in subtype of endometrioid/endometrioid histology have a favorable overall prognosis.

Chiang et al. [18] showed that early stage of synchronous cancer had a more significant influence on survival than histology type though they also reported that patients with concordant endometrioid endometrial and ovarian tumors had a good survival potential and prognosis. In our study, there were no deaths in patients with concordant stage I as well as concordant grade 1 endometrial and ovarian cancers. On the other hand, in patients with at least one stage III synchronous cancer, the proportion of patients who survived was 64.3% (9/14). Though endometriosis was seen in 58.7% of our cases, it was not found to be associated with an increased risk of mortality (p=0.953).

Compared to other papers, the focus of our study was to look at patients with purely endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the uterus and epithelial ovarian cancer. The main limitation of our study is that it is a retrospective study with limited numbers as a result of excluding non endometrioid types of endometrial uterine cancers. However, due to the rarity of this type of condition and the fact that diagnosis is usually made after primary surgery, it is difficult to recruit patients in a prospective study. Nevertheless, our study does show that women with synchronous primary endometrial and ovarian cancer were younger at age of diagnosis, with the majority presenting with early stage disease and good overall survival.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Zaino R, Whitney C, Brady MF, DeGeest K, Burger RA, Buller RE. Simultaneously detected endometrial and ovarian carcinomas: a prospective clinicopathologic study of 74 cases: a gynecologic oncology group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2001. 83:355–362.

2. Woodruff JD, Solomon D, Sullivant H. Multifocal disease in the upper genital canal. Obstet Gynecol. 1985. 65:695–698.

3. Eisner RF, Nieberg RK, Berek JS. Synchronous primary neoplasms of the female reproductive tract. Gynecol Oncol. 1989. 33:335–339.

4. Scully RE, Young RH, Clement PB. Tumors of the ovary, maldeveloped gonads, fallopian tube and broad ligament. Atlas of tumor pathology. 1998. Bethesda, MD: Washington Armed Forces Institute of Pathology.

5. Soliman PT, Slomovitz BM, Broaddus RR, Sun CC, Oh JC, Eifel PJ, et al. Synchronous primary cancers of the endometrium and ovary: a single institution review of 84 cases. Gynecol Oncol. 2004. 94:456–462.

6. Caldarella A, Crocetti E, Taddei GL, Paci E. Coexisting endometrial and ovarian carcinomas: a retrospective clinicopathological study. Pathol Res Pract. 2008. 204:643–648.

7. Gemer O, Bergman M, Segal S. Ovarian metastasis in women with clinical stage I endometrial carcinoma. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004. 83:208–210.

8. Ulbright TM, Roth LM. Metastatic and independent cancers of the endometrium and ovary: a clinicopathologic study of 34 cases. Hum Pathol. 1985. 16:28–34.

9. Shenson DL, Gallion HH, Powell DE, Pieretti M. Loss of heterozygosity and genomic instability in synchronous endometrioid tumors of the ovary and endometrium. Cancer. 1995. 76:650–657.

10. Fujita M, Enomoto T, Wada H, Inoue M, Okudaira Y, Shroyer KR. Application of clonal analysis. Differential diagnosis for synchronous primary ovarian and endometrial cancers and metastatic cancer. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996. 105:350–359.

11. Lin WM, Forgacs E, Warshal DP, Yeh IT, Martin JS, Ashfaq R, et al. Loss of heterozygosity and mutational analysis of the PTEN/MMAC1 gene in synchronous endometrial and ovarian carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 1998. 4:2577–2583.

12. Ricci R, Komminoth P, Bannwart F, Torhorst J, Wight E, Heitz PU, et al. PTEN as a molecular marker to distinguish metastatic from primary synchronous endometrioid carcinomas of the ovary and uterus. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2003. 12:71–78.

13. Moreno-Bueno G, Gamallo C, Perez-Gallego L, de Mora JC, Suarez A, Palacios J. Beta-Catenin expression pattern, betacatenin gene mutations, and microsatellite instability in endometrioid ovarian carcinomas and synchronous endometrial carcinomas. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2001. 10:116–122.

14. Kaneki E, Oda Y, Ohishi Y, Tamiya S, Oda S, Hirakawa T, et al. Frequent microsatellite instability in synchronous ovarian and endometrial adenocarcinoma and its usefulness for differential diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 2004. 35:1484–1493.

15. Shannon C, Kirk J, Barnetson R, Evans J, Schnitzler M, Quinn M, et al. Incidence of microsatellite instability in synchronous tumors of the ovary and endometrium. Clin Cancer Res. 2003. 9:1387–1392.

16. Dubeau L. The cell of origin of ovarian epithelial tumours. Lancet Oncol. 2008. 9:1191–1197.

17. Eifel P, Hendrickson M, Ross J, Ballon S, Martinez A, Kempson R. Simultaneous presentation of carcinoma involving the ovary and the uterine corpus. Cancer. 1982. 50:163–170.

18. Chiang YC, Chen CA, Huang CY, Hsieh CY, Cheng WF. Synchronous primary cancers of the endometrium and ovary. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008. 18:159–164.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download