Abstract

Secure reconstruction of multiple hepatic ducts that are severely damaged by tumor invasion or iatrogenic injury is a challenge. Failure of percutaneous or endoscopic biliary stenting requires lifelong placement of one or more percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) tubes. For such difficult situations, we devised a surgical technique termed cluster hepaticojejunostomy (HJ), which can be coupled with palliative bile duct resection. The cluster HJ technique consisted of applying multiple internal biliary stents and a single wide porto-enterostomy to the surrounding connective tissues. The technique is described in detail in the present case report. Performing cluster HJ benefits from three technical tips as follows: making the multiple bile duct openings wide and parallel after sequential side-to-side unification; radially anchoring and traction of the suture materials at the anterior anastomotic suture line; and making multiple segmented continuous sutures at the posterior anastomotic suture line. Thus, cluster HJ with radial spreading anchoring traction technique is a useful surgical method for secure reconstruction of severely damaged hilar bile ducts.

Extensive surgical resection is often abandoned on identification of wide and deep tumor invasion at the hilar bile duct intraoperatively, because it is difficult to achieve curative resection. On determining that curative resection of the perihilar cholangiocarcinoma is not possible, an intraoperative decision about whether or not to perform palliative bilio-enteric bypass surgery must be made. In patients with complex separation of the hilar bile ducts, it is often difficult to insert multiple biliary stents percutaneously through percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) or endoscopic retrograde cholangiography approach, as well as maintain them successfully for a prolonged time. A majority of these patients are required to keep one or more PTBD tubes with or without endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage (ERBD).123456 In such intractable situations, palliative bilio-enteric bypass to remove PTBD tubes is seriously considered as a measure to improve the quality of life. However, bilio-enteric bypass for multiple separate hilar bile ducts is technically demanding, and its patency is also much shorter than expected because multiple bilio-enteric anastomoses are often performed to the residual tumor tissue itself. Biliary reconstruction is difficult in extensive hilar bile duct necrosis resulting from iatrogenic bile duct injury, similar to cases of advanced perihilar cholangiocarcinoma.2

For such difficult biliary reconstruction, we devised a surgical technique termed cluster hepaticojejunostomy (HJ) that involves placement of multiple biliary stents and single wide porto-enterostomy on the surrounding connective tissue.7 We have performed the cluster HJ technique in more than 20 cases so far, indicative of its clinical applicability. Herein, we present the technical details of cluster HJ with discussion on further modification.

In patients with advanced perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, resectability is usually determined after dissection of the hepatoduodenal ligament. Once it is decided to perform palliative bile duct resection (BDR) for bilio-enteric drainage, the infiltrated hilar bile duct mass is transected without further dissection at the level of the hilar plate. Retrograde approach toward the hilar bile duct through longitudinal incision of the distal common bile duct often provides wide exposure of the involved hilar bile ducts.

At the transected bile duct cut surface, major bile duct openings, which typically include four hepatic ducts each from the right anterior and posterior sections, and left medial and lateral sections, are meticulously identified with the use of the preoperative imaging studies as a road map; and subsequently, the dilated caudate ducts (usually two or three in number) are identified. It is essential to open all dilated intrahepatic ducts because any missed bile duct can result in late onset of cholangitis.

All hilar bile duct openings are fully dilated with blunt tonsil clamps. Silastic stents of three different sizes (obtained by cutting the silastic T-tubes with outer diameters of 3, 4, and 5 mm) are inserted into each opening after size matching. A larger-sized tube is preferentially used to accommodate future progressive tumor encroachment. An over-sized stent tube is inserted tightly through each intrahepatic duct. One or two side holes are made only at the intrahepatic-side ends of the stent tubes, because the tumor can grow into the stent tube through the side holes around the HJ site. Bleeding from the bile duct cut surface or hilar plate should be meticulously sutured because it can be a source of hemobilia. Unification ductoplasty is also attempted at two adjacent bile duct openings, by which three or four duct openings can be unified sequentially.

A routine Roux-en-Y jejunal limb is prepared and pulled up through the retrocolic tunnel. A longitudinal incision is made at the antemesenteric border and posterior wall anastomosis was performed with two or three segmented continuous running sutures with 5-0 Prolene. Since we designed one continuous suture to cover each 1 cm-length of the posterior suture line, three segmented continuous sutures were necessary for a 3 cm-wide bile duct opening.

Subsequently, each silastic internal stent was inserted and securely transfixed with 5-0 Prolene. Anterior wall anastomosis was done through multiple interrupted sutures at 1.5 mm intervals (25 to 40 sutures). At the start of HJ, multiple suture materials with double-arm needles were radially placed to spread the bile duct opening. This radial spreading anchoring traction technique is important to perform cluster HJ because it provides a good operative field, as well as facilitates secure full-thickness anastomosis of the anterior wall. Very meticulous water-tight anterior wall anastomosis is required because anastomosis to the residual tumor tissue per se can result in anastomotic failure.

The intraoperative leak test with diluted methylene blue solution is performed through the pre-existing PTBD tubes. The PTBD tube is not removed during surgery, and kept until follow-up tube cholangiography and/or radioisotope hepatobiliary scintigraphy, usually 2 weeks after surgery.

A 72-year-old male patient was referred from other hospital with two PTBD tubes due to perihilar cholangiocarcinoma of Bismuth-Corlette type IV. The patient suffered from concurrent acute pancreatitis. Thus, the surgical procedure was planned at 3 weeks after resolution of obstructive jaundice and pancreatitis. Despite locally advanced tumor, we decided to perform resection.

During laparotomy, we identified that the left portal vein and left hepatic artery were encased as well as the second-order branches of the right hepatic ducts were deeply involved by the tumor. Thus, we abandoned curative resection and decided to perform palliative BDR with cluster HJ.

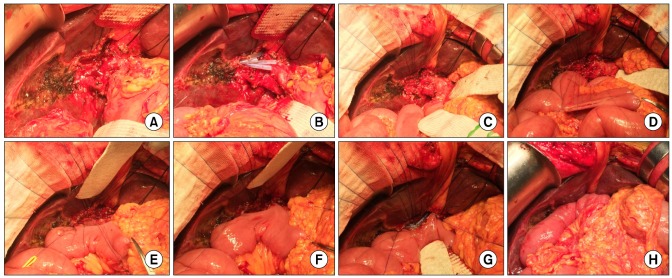

The patient had total destruction of hilar bile duct structures, hence the tumor over the right hepatic artery was removed (Fig. 1A). Four intrahepatic bile duct openings (3 from the right liver and 1 from the left liver) were identified and their edges were repaired to prepare them for anastomosis; subsequently, four size-matched silastic stents were temporarily inserted (Fig. 1B). The caudate ducts were not markedly dilated, thus small coronary dilators were inserted to identify their course. The anterior wall of the bile duct opening was anchored with multiple 5-0 Prolene sutures (Fig. 1C). The posterior wall of the bile duct opening was continuously sutured with 5-0 Prolene sutures after dividing into 3 segments with 2 internal intervening sutures (Fig. 1D-F). The corner stitches were retracted with rubber vessel loops to make the operative field wide. Four silastic stents and one additional stent were firmly inserted into each beaked bile duct opening after forceful mechanical dilatation, and then transfixed with 5-0 Prolene suture (Fig. 1G). The anterior wall was finally closed by using interrupted sutures that were previously anchored (Fig. 1H). After these surgical procedures, a leak test was performed with injection of methylene blue solution through the pre-existing PTBD tube.

The patient recovered uneventfully without any noticeable complication, and is currently undergoing adjuvant chemoradiation therapy.

Due to recent advances in radiological and endoscopic interventions, biliary stenting has become a widely performed technique for treatment of biliary strictures. Its advantages are that it is minimally invasive and well tolerated in a majority of patients. Application of biliary stents as palliative treatment of biliary malignancies is widely accepted in clinical practice.8 Furthermore, retrievable biliary stents are also used for treatment of benign biliary strictures.91011 However, various stent-associated complications, such as stent occlusion and cholangitis, restrict their wide use in benign strictures. Although biliary stents can be deployed endoscopically or radiologically with acceptably low risk, their long-term patency is still regarded as suboptimal.12 Therefore, surgery has major advantages on anastomotic patency, especially for treatment of benign bile duct diseases.

For reconstruction of multiple bile ducts, various surgical techniques with multiple separate anastomoses with or without unification ductoplasty have been introduced. A healthy duct stump is a prerequisite for such surgical techniques, thus it is usually not appropriate to apply them to tumor-infiltrated bile duct stumps. Therefore, we developed a reliable surgical technique of cluster HJ that would enable secure reconstruction of severely damaged hilar bile ducts.

Because residual tumors at the hepatic hilum grow progressively after palliative BDR of R2 resection, occlusion is expected in any HJ. This sequence suggests that duct-to-mucosa approximation is not necessary because it is not technically possible or reasonable. Instead, duct luminal patency can be obtained through application of internal silastic stents. If the internal stent is properly placed, the corresponding intrahepatic bile duct will remain open. For this purpose, we cut a silastic T-tube to a length of 4-5 cm and introduced one or two side-holes at its peripheral end only, for an internal stent crossing HJ. Other types of thin-walled silastic tubes are not recommended because such internal stents need to endure the strong compression pressure caused by tumor progression. Secure outer anastomosis is important to prevent anastomotic leak; thus any connective tissue at the hepatic hilum should be preserved even if the tissue appears to be invaded by the tumor. This surgical procedure of cluster HJ is comparable to the Kasai procedure, which is a porto-enterostomy performed by suturing a jejunal loop to the hepatic parenchyma that surrounds the transected hepatic ducts.1314

We have sporadically applied cluster HJ to patients with iatrogenic bile duct injury prior to our previous report.7 After a phase in our learning curve, we recognized that cluster HJ has a better patency rate than other more conventional reconstruction methods. The results of our previous study indicated that cluster HJ is a useful surgical technique for the secure reconstruction of severely damaged hilar bile ducts. Thus far, we have sporadically performed cluster HJ with satisfactory mid-term patency outcomes in more than 20 patients who were indicated.

After palliative BDR for unresectable perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, the primary aim is to prevent the insertion of additional PTBD for at least the first 6 months. Usually, the life expectancy of patients who require additional PTBD is much shortened; thus, this practice should be avoided if possible, until it is clearly beneficial for the patient. As the tumor progressed, some intrahepatic ducts began to be dilated according to the status of biliary obstruction although internal stents appeared to be kept in their position. Since the silastic T-tube segment has a radio-opaque line, its location can be exactly determined on the liver computed tomography images. Proper positioning of the corresponding internal stent on computed tomography images is indicative of a theoretically opened intrahepatic duct, despite considerable degree of possible stricture across the stent. Hence, non-absorbable suture material (5-0 Prolene) was used for transfixation of the internal stents, to ensure that the stents would be not displaced too early.

Three technical tips could facilitate an efficient cluster HJ. The first is to make the multiple bile duct openings wide and parallel after sequential side-to-side unification. There is no limitation in the width of unified bile duct openings, thus a unified opening of 5 cm in width can be readily acceptable for cluster HJ. The second is to radially anchor the traction suture materials at the anterior anastomotic line. We suggest an interval of 1.5 mm, thus a large bile duct opening requires numerous anterior sutures. The third is to make multiple segmented continuous sutures with a suggested interval of 8-10 mm; thus, 2 or 3 intervening sutures are usually necessary for most sizable bile duct openings.

Secure performance of biliary reconstruction is also important to perform timely, postoperative concurrent chemoradiation therapy. We usually recommend such adjuvant therapy to all patients undergoing R1 or R2 resection regardless of patient age because nearly all patients who have recovered from cluster HJ can tolerate such adjuvant anti-tumor therapy.

In conclusion, cluster HJ is a useful technique that is clinically applicable. To enhance its reliability, it will be necessary to perform cluster HJ in a larger number of patients including those with benign hilar bile duct injury.

References

1. Hwang S, Song GW, Ha TY, Lee YJ, Kim KH, Ahn CS, et al. Reappraisal of percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage tract recurrence after resection of perihilar bile duct cancer. World J Surg. 2012; 36:379–385. PMID: 22159824.

2. Hwang S, Lee SG, Lee YJ, Ahn CS, Kim KH, Moon DB, et al. Treatment of recurrent bile duct stricture after primary reconstruction for laparoscopic cholecystectomy-induced injury. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2008; 18:445–448. PMID: 18936662.

3. Law R, Baron TH. Bilateral metal stents for hilar biliary obstruction using a 6Fr delivery system: outcomes following bilateral and side-by-side stent deployment. Dig Dis Sci. 2013; 58:2667–2672. PMID: 23625287.

4. Maillard M, Novellas S, Baudin G, Evesque L, Bellmann L, Gugenheim J, et al. Placement of metallic biliary endoprostheses in complex hilar tumours. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2012; 93:767–774. PMID: 22921689.

5. Lee TH, Park do H, Lee SS, Choi HJ, Lee JK, Kim TH, et al. Technical feasibility and revision efficacy of the sequential deployment of endoscopic bilateral side-by-side metal stents for malignant hilar biliary strictures: a multicenter prospective study. Dig Dis Sci. 2013; 58:547–555. PMID: 22886596.

6. Sangchan A, Kongkasame W, Pugkhem A, Jenwitheesuk K, Mairiang P. Efficacy of metal and plastic stents in unresectable complex hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012; 76:93–99. PMID: 22595446.

7. Ha TY, Hwang S, Song GW, Jung DH, Kim MH, Lee SG, et al. Cluster hepaticojejunostomy is a useful technique enabling secure reconstruction of severely damaged hilar bile ducts. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015; 19:1537–1541. PMID: 25956723.

8. Abraham NS, Barkun JS, Barkun AN. Palliation of malignant biliary obstruction: a prospective trial examining impact on quality of life. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002; 56:835–841. PMID: 12447294.

9. Judah JR, Draganov PV. Endoscopic therapy of benign biliary strictures. World J Gastroenterol. 2007; 13:3531–3539. PMID: 17659703.

10. Tsukamoto T, Hirohashi K, Kubo S, Tanaka H, Hamba H, Shuto T, et al. Self-expanding metallic stent for benign biliary strictures: seven-year follow-up. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004; 51:658–660. PMID: 15143886.

11. Tocchi A, Mazzoni G, Liotta G, Costa G, Lepre L, Miccini M, et al. Management of benign biliary strictures: biliary enteric anastomosis vs endoscopic stenting. Arch Surg. 2000; 135:153–157. PMID: 10668872.

12. Siriwardana HP, Siriwardena AK. Systematic appraisal of the role of metallic endobiliary stents in the treatment of benign bile duct stricture. Ann Surg. 2005; 242:10–19. PMID: 15973096.

13. Kasai M, Kimura S, Asakura Y, Suzuki H, Taira Y, Ohashi E. Surgical treatment of biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 1968; 3:665–675.

14. Gao JB, Bai LS, Hu ZJ, Wu JW, Chai XQ. Role of Kasai procedure in surgery of hilar bile duct strictures. World J Gastroenterol. 2011; 17:4231–4234. PMID: 22072856.

Fig. 1

Surgical procedures of cluster hepaticojejunostomy. The hilar tumor was removed (A) and multiple intrahepatic bile duct openings were exposed with insertion of stent tubes (B). The anterior wall of the bile duct opening was anchored with multiple 5-0 Prolene sutures (C). The posterior wall of the bile duct opening was segmented into 3 parts by two internal intervening sutures (D); these intervening sutures were tied (E); and completed the posterior wall anastomosis (F). During the posterior wall suturing, each corner stitch was retracted with a rubber vessel loop to widen the operative field. Five internal stents were firmly inserted into each bile duct opening, and separately transfixed with 5-0 Prolene suture (G). The anterior wall was finally closed with interrupted sutures (H).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download