Abstract

Backgrounds/Aims

Intrahepatic cholangiocacinoma (IHCC) can result in spread of tumor cells to the lymph nodes (LNs) around the gastric lesser curvature. Extensive dissection of the gastric lesser curvature can induce injury to the extragastric vagus nerve branches that control motility of the pyloric sphincter and result in intractable gastric stasis. Herein, we presented our experience of preventive pyloroplasty added to resection of IHCC to address dissection-induced gastric stasis in 6 patients during 15-years.

Methods

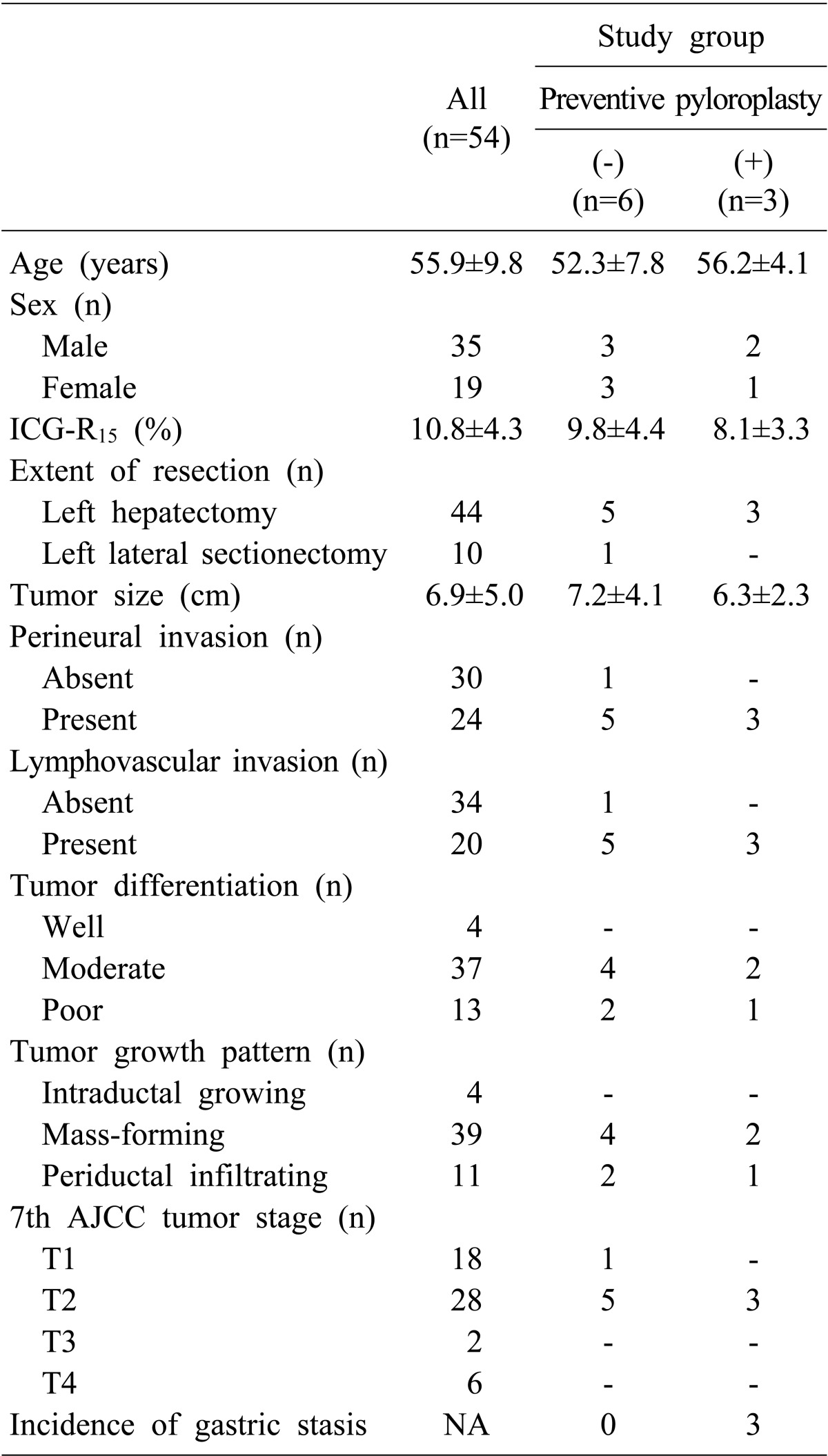

We analyzed the survival outcomes of 54 IHCC patients presenting left-sided LN metastasis. Nine study patients who underwent extended left-sided LN dissection including lesser curvature LN dissection were selected and divided into 2 groups according to performance of preventive pyloroplasty and the incidence of gastric stasis was analyzed.

Results

All 54 patients were classified as stage IV due to T1-3N1M0 stage. The tumor recurrence rate were 56.4% at 1 year, 84.3% at 3 years and 84.3% at 5 years; and the overall patient survival rate were 51.9% at 1 year, 13.6% at 3 years and 6.8% at 5 years. In all 3 study patients who did not receive pyloroplasty, overt postoperative gastric stasis persisted for >10 days leading to prolonged hospital stay. In contrast, none of the 6 study patients who underwent pyloroplasty suffered from gastric stasis.

The lymph node (LN) spread patterns of intrahepatic cholangiocacinoma (IHCC) include the common hepatic artery, celiac axis and even the lesser curvature side of the stomach as sites of regional LN metastasis if IHCC is located at the left liver.12 This pattern of LN spread is regarded as left-sided LN metastasis. Such LN metastasis requires dissection of the gastric lesser curvature to achieve complete LN dissection in addition to hepatectomy and dissection of the hepatoduodenal ligament and celiac axis.

Additional extensive LN dissection at the gastric lesser curvature does not improve survival outcomes, since the tumor is regarded as stage IV tumor according to the 7th American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system.34 LNs at the lesser curvature can only be sampled, preserving some connective tissue corresponding to the gastric serosal layer. Meanwhile, if there are some enlarged LNs that are not easily distinguished from metastatic LNs, such LN sampling is insufficient from the standpoint of surgical oncology. LN dissection at the lesser curvature may lead to irreversible injury to the vagus nerve branches that control the motility of the pyloric sphincter. As a result, intractable gastric stasis can occur and hospital stay is prolonged due to dietary problems.5 Since such patients are usually diagnosed stage IV IHCC, their expected life span is relatively short; hence, such gastric stasis-associated prolonged hospital stay cannot be overlooked as a negligible complication.4

We added the procedure of pyloroplasty after hepatectomy and LN dissection of the hepatoduodenal ligament and gastric lesser curvature to address dissection-induced gastric stasis, if indicated. Herein, we presented our experience of preventive pyloroplasty added to resection of IHCC in 6 patients during 15-years.

The liver cancer database of our institution was searched to identify patients who underwent primary surgical treatment for IHCC from January 1998 to December 2013. Their overall patient profiles and survival outcomes were presented previously.4 We selected IHCC patients presenting the left-sided LN metastasis (n=54). They underwent left hepatectomy or left lateral sectionectomy with LN sampling or extensive dissection of the left-sided LNs. All surgeries were regarded as macroscopic curative resection despite presence of regional LN metastasis. These patients with left-sided IHCC and left-sided LN metastasis were used to analyze the tumor recurrence and patient survival outcomes.

Because preventive pyloroplasty was performed by only one surgeon (SH), the patients were again limited to the 9 study patients who underwent extensive left-sided LN dissection including lesser curvature dissection. Subsequently, they were divided into 2 groups i.e., pyloroplasty group (n=6) and no-pyloroplasty group (n=3) according to performance of preventive pyloroplasty. The development of postoperative gastric stasis was compared between these two groups.

Medical records were retrospectively reviewed after approval of the Institutional Review Board of our institution. Patients were followed until November 2015 with institutional medical record review.

The nasogastric tube was usually removed at 1 day after hepatectomy in the patients who had undergone left hepatectomy. If biliary reconstruction with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy was performed, the nasogastric tube was kept for 3 days. If gastric stasis was suspected, the nasogastric tube was maintained until recovery of gastric motility function. If necessary, erythromycin and/or domperidone were administered through the nasogastric tube with expected facilitation of recovery of bowel motility.67 During fasting, all patients received total parenteral nutrition. After discharge from hospital, the patients who had suffered from delayed gastric emptying were followed up every 1–2 months during the first year primarily due to delayed recovery of the gastrointestinal motility.

The decision to perform preventive pyloroplasty following hepatectomy and LN dissection was made after consideration of the anatomy of the extrinsic vagal innervation. We performed the classical hand-sewing pyloroplasty of Heineke-Mikulicz type. The wall of the distal stomach and duodenal first portion was longitudinally incised with electrocautery and then transversely repaired by inner continuous sutures using 4–0 absorbable monofilament and outer continuous sutures using 5–0 non-absorbable monofilament or interrupted sutures with 4–0 black silk (Fig. 1).

IHCC patients were followed up every 1–3 months at the outpatient clinic depending on tumor stage during the first year after surgery, and thereafter, every 3–4 months for >5 years. The general principles of treatment for recurrent IHCC lesions were applied to our patients and every available treatment modality was performed. Patients underwent systemic chemotherapy if locoregional treatment failed or was not indicated. Detailed follow-up protocol was presented previously.4

Numerical data were reported as mean with standard deviation. Incidence was compared with the Fisher's exact. Survival curves were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. A p-value <0.1 was considered statistically significant considering the small sample size. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 20; IBM, New York, NY).

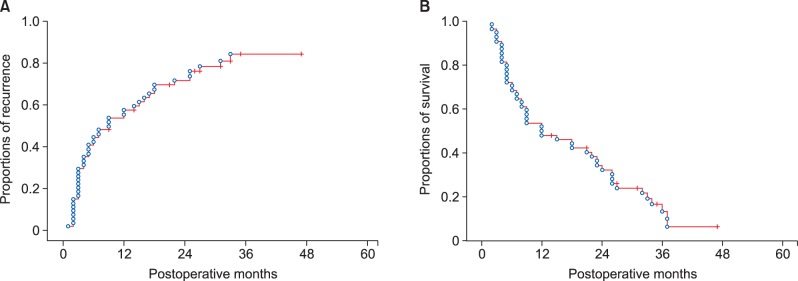

All 54 patients were classified as stage IV according to the 7th AJCC staging system because of T1-3N1M0 stage. Their clinicopathological profiles were summarized in Table 1. The tumor recurrence rate were 56.4% at 1 year, 84.3% at 3 years and 84.3% at 5 years; and overall patient survival rate were 51.9% at 1 year, 13.6% at 3 years and 6.8% at 5 years (Fig. 2).

All 3 patients of the no-pyloroplasty study group showed overt postoperative gastric stasis persisting for > 10 days. The nasogastric tube was removed in 1 patient at postoperative day 2, but it was reinserted due to nausea and epigastric fullness. The patient was required to keep the nasogastric tube for 16 days despite medication with erythromycin and domperidone. In the other 2 patients, the nasogastric tube was kept for 11 days and 20 days. All patients received total parenteral nutrition during fasting. Complete recovery to the normal dietary pattern was achieved 2 to 6 months after removal of the nasogastric tube.

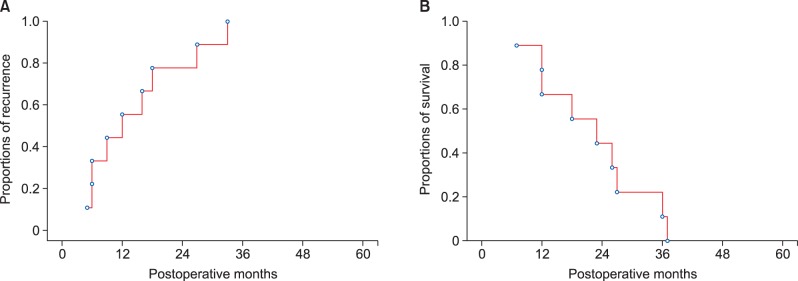

After experiencing LN dissection-induced gastric stasis in these 3 patients, we have performed preventive pyloroplasty if indicated. All 6 study patients who underwent pyloroplasty kept the nasogastric tube for the first 3 days and none showed any evidence of gastric stasis during the first postoperative week or during the later follow-up (p=0.09). The patient survival outcomes were poor due to very high recurrence rates despite adjuvant therapy (Fig. 3). Uneventful recovery from surgical resection appeared to be beneficial to these patients although survival benefit from extensive LN dissection was not evident in this study.

IHCC is the second most common primary malignancy of the liver. Although its incidence is gradually rising, it is still uncommon, as compared with HCC. In our institutional liver cancer database, IHCC accounted for approximately 15% of primary liver malignancies that underwent surgical resection.4

LN metastasis is the important prognostic factor in most gastrointestinal malignancies including IHCC.489 Our results indicated that the significant risk factors for post-resection survival of IHCC were the pattern of tumor growth (odds ratio=0.61-1.02), perineural invasion (odds ratio=1.39) and LN metastasis (odds ratio=2.08).4 LN metastasis alone is classified as the tumor stage IV according to the 7th AJCC staging system for IHCC. Because LN dissection is not routinely performed for patients with IHCC in many centers worldwide, some LN metastasis could be missed, leading to an unexpectedly poor survival outcome. In contrast, LN metastasis itself is associated with very poor outcomes and the clinical benefit of routine LN dissection thus remains unknown.910 LN dissection should be strongly considered for IHCC because it provides essential information on nodal status for accurate tumor staging and up to 30% of patients may have LN metastasis.1112

If multiple enlarged LNs are identified in the operative field of IHCC patients, a majority of hepatobiliary surgeons may try to dissect all LNs that appear resectable. Such an aggressive approach can lead to expansion of LN dissection area to the gastric lesser curvature because LN sampling is often not sufficient for oncological LN removal. Because the left gastric artery and celiac axis area is the common site of LN location regardless of tumor metastasis, extensive LN dissection often leads to excessive clearing of the gastric lesser curvature and ligation of the left gastric artery. This surgical procedure can induce an injury to the vagus nerve branches that control motility of the pyloric sphincter leading to intractable gastric stasis. Based on our experience of LN dissection at the lesser curvature in gastric cancer surgery, the vagus nerve branch to the antropyloric junction cannot be saved. Unlike gastric cancer surgery, surgical resection of IHCC leaves the pylorus intact, thus a motility disorder of the pyloric sphincter can develop.

This denervation of controlling vagus nerve branches usually manifests as delayed gastric emptying that persists up 1–2 months. Thereafter, the patient also often complains of the sensation of a gas-filled stomach over several months. In fact, gastrointestinal functions are regulated not only by extragastric vagus nerves but also by intramural plexuses via numerous neuropeptide transmitters.13 These symptoms are usually self-limited and resolve slowly and spontaneously with time. However, it results in deteriorated quality of life because patients have to restrict oral intake for a few weeks after surgery or keep a nasogastric tube until restoration of gastric motility. Considering the poor prognosis of IHCC patients with LN metastasis, gastric stasis and its associated deteriorating quality of life cannot be overlooked as a negligible complication.

In reality, left hepatectomy per se is also associated with disorders of gastric motility. After living-donor left hepatectomy, the stomach can become adhered to the liver cut surface that can cause unwanted gastric stasis. Despite its usually low incidence, one report indicated an incidence of 23% in their small-volume series.141516 The underlying mechanisms of gastric stasis after left hepatectomy differ from those of the usual laparotomy-associated adhesive ileus, possibly due to dislocation of the stomach after left hepatectomy and adhesion between the stomach and cut surface of the liver.16 In a report of 45 left liver donors, a unique method of omental patching between the cut surface of the liver and the stomach resulted in only 1 case (2%) of gastric stasis.16

We have performed pyloroplasty as the last procedure during resection of IHCC with left-sided LN metastasis, in order to address LN dissection-induced gastric stasis. Prolonged gastric stasis universally occurred in patients who had undergone extensive dissection of the gastric lesser curvature, but it disappeared completely after pyloroplasty. Conventional Heineke-Mikulicz type pyloroplasty is a very simple procedure taking only 10 minutes because the pylorus area is usually normal in such IHCC patients. The results of this study indicated that pyloroplasty is indicated in cases with anticipated postoperative gastric stasis.

In conclusion, pyloroplasty is a useful surgical option to prevent gastric stasis when extensive left-sided LN dissection is required in IHCC patients with LN metastasis who have very poor post-resection prognosis.

References

1. Tsuji T, Hiraoka T, Kanemitsu K, Takamori H, Tanabe D, Tashiro S. Lymphatic spreading pattern of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Surgery. 2001; 129:401–407. PMID: 11283529.

2. Morine Y, Shimada M, Utsunomiya T, Imura S, Ikemoto T, Mori H, et al. Clinical impact of lymph node dissection in surgery for peripheral-type intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Surg Today. 2012; 42:147–151. PMID: 22124809.

3. Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A 3rd. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer;2010.

4. Hwang S, Lee YJ, Song GW, Park KM, Kim KH, Ahn CS, et al. Prognostic impact of tumor growth type on 7th AJCC staging system for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a single-center experience of 659 cases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015; 19:1291–1304. PMID: 25820487.

5. Shafi MA, Pasricha PJ. Post-surgical and obstructive gastroparesis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2007; 9:280–285. PMID: 17883974.

6. Lee A. Gastroparesis: what is the current state-of-the-art for evaluation and medical management? What are the results? J Gastrointest Surg. 2013; 17:1553–1556. PMID: 23801519.

7. Stevens JE, Jones KL, Rayner CK, Horowitz M. Pathophysiology and pharmacotherapy of gastroparesis: current and future perspectives. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013; 14:1171–1186. PMID: 23663133.

8. Nathan H, Aloia TA, Vauthey JN, Abdalla EK, Zhu AX, Schulick RD, et al. A proposed staging system for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009; 16:14–22. PMID: 18987916.

9. Clark CJ, Wood-Wentz CM, Reid-Lombardo KM, Kendrick ML, Huebner M, Que FG. Lymphadenectomy in the staging and treatment of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a population-based study using the National Cancer Institute SEER database. HPB (Oxford). 2011; 13:612–620. PMID: 21843261.

10. Adachi T, Eguchi S. Lymph node dissection for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a critical review of the literature to date. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014; 21:162–168. PMID: 24027075.

11. Ribero D, Pinna AD, Guglielmi A, Ponti A, Nuzzo G, Giulini SM, et al. Italian Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma Study Group. Surgical approach for long-term survival of patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a multi-institutional analysis of 434 patients. Arch Surg. 2012; 147:1107–1113. PMID: 22910846.

12. de Jong MC, Nathan H, Sotiropoulos GC, Paul A, Alexandrescu S, Marques H, et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: an international multi-institutional analysis of prognostic factors and lymph node assessment. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29:3140–3145. PMID: 21730269.

13. Becker HD, Herfarth C, Lierse W, Schreiber HW. Surgery of the stomach: indications, methods, complications. Berlin: Springer-Verlag;1986. p. 182–184.

14. Lo CM. Complications and long-term outcome of living liver donors: a survey of 1,508 cases in five Asian centers. Transplantation. 2003; 75(3 Suppl):S12–S15. PMID: 12589131.

15. Hwang S, Lee SG, Lee YJ, Sung KB, Park KM, Kim KH, et al. Lessons learned from 1,000 living donor liver transplantations in a single center: how to make living donations safe. Liver Transpl. 2006; 12:920–927. PMID: 16721780.

16. Kinoshita A, Takatsuki M, Hidaka M, Soyama A, Eguchi S, Kanematsu T. Prevention of gastric stasis by omentum patching after living donor left hepatectomy. Surg Today. 2012; 42:816–818. PMID: 22451247.

Fig. 1

The images of extragastric vagus nerve innervation (A), left hepatectomy with extensive left-sided lymph node dissection (B), and post-pyloroplasty status (C). A dotted circle indicates the area of vagus nerve injury.

Fig. 2

Cumulative tumor recurrence (A) and overall patient survival (B) curves after macroscopic curative resection of left-sided intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with lymph node metastasis.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download