This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Backgrounds/Aims

We investigated the clinical application of extended distal pancreatectomy in patients with pancreatic neck cancer accompanied by distal pancreatic atrophy. In this study, we have emphasized on the technical aspects of using the linear stapling device for a bulky target organ.

Methods

From March 2010 to September 2013, 46 patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, who underwent pancreatic resection with radical intent at our institute, were reviewed retrospectively. Among them, three patients (6.5%) underwent extended distal pancreatectomy. A linear stapling device and vise-grip locking pliers were used for en bloc resection of the distal pancreas, first duodenal portion, and distal common bile duct. The results were compared with those after standard pancreatectomy.

Results

All three patients presented with jaundice, and the ratio of pancreatic duct to parenchymal thickness of the pancreatic body was greater than 0.5. Grade A pancreatic fistula developed in all of the cases, but none of these fistulae were lethal. Pathological staging was T3N1M0 in all of the patients. The postoperative daily serum glucose fluctuations and insulin requirements were comparable to those in patients who received pancreaticoduodenectomy or distal pancreatectomy. At the last follow-up, two patients were alive with liver metastasis at 4 and 10 months postoperatively, respectively, and one patient died of liver metastasis at 5 months postoperatively.

Conclusions

While the prognosis of advanced pancreatic neck adenocarcinoma is still dismal, extended distal pancreatectomy is a valid treatment option, especially when there is atrophy of the distal pancreas. Also, the procedure is technically feasible, and further refinement is necessary to improve patient survival.

Go to :

Keywords: Pancreas, Neck, Adenocarcinoma, Pancreatectomy, Atrophy

INTRODUCTION

Surgical removal provides the best survival benefits for patients with pancreatic neck cancer, although the results are still dismal.

1 Two options are considered to be the standard of care, pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) and distal (subtotal) pancreatectomy (DP), depending on the tumor location.

2 In patients presenting with jaundice, the preferred treatment of choice is PD, since the usual resection line for DP is the portal vein, precluding radical operation.

However, if the patient has atrophy of the distal pancreas due to long-standing pancreatic duct obstruction, there are concerns regarding postoperative endocrine and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Although it is technically challenging, an extended distal pancreatectomy (EDP), preserving only the uncinate process of the pancreas, can be an alternative treatment option. EDP can also avoid pancreaticoenterostomy, which is the most compromised anastomosis of the pancreatic resection procedures. In this paper we present our experience with special emphasis on the technical aspects of using the linear stapling device for bulky target organs.

Go to :

PATIENTS AND METHODS

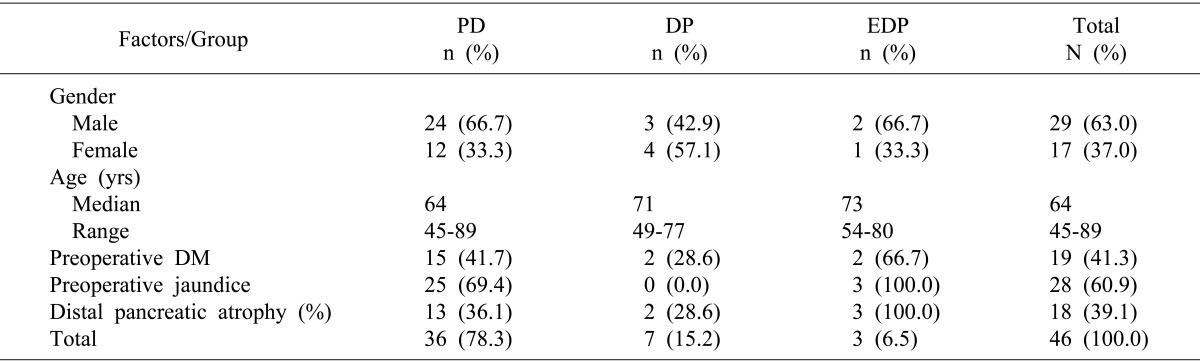

From March 2010 to September 2013, a total of 47 patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma underwent pancreatic resection with radical intent at our institute. Among them, 46 patients were included in this study and reviewed retrospectively, excluding one patient who received total pancreatectomy. Among these 46 patients, three patients (6.5%) underwent EDP; 36 patients (78.3%) underwent PD; and seven patients (15.2%) underwent DP. All three patients in the EDP group presented with jaundice, and two patients presented with preoperative diabetes (

Table 1). During the same period, one patient (2.1%) died of upper gastrointestinal bleeding at 31 days after PD.

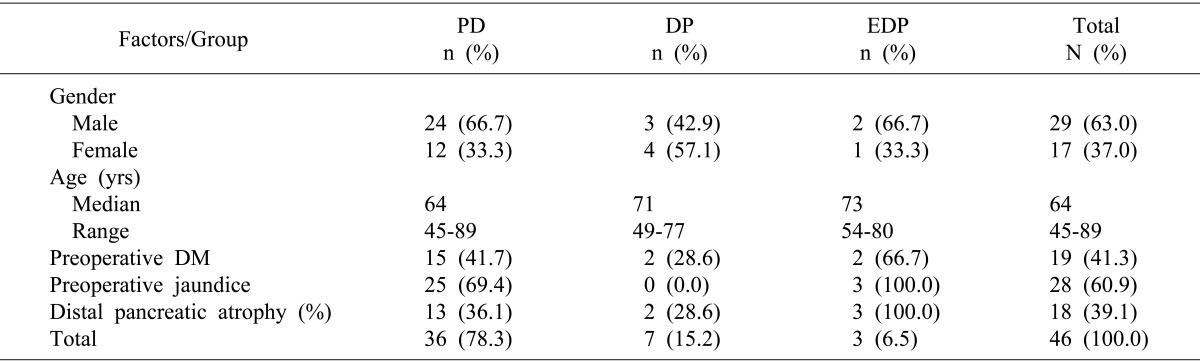

Table 1

Demographic and preoperative data

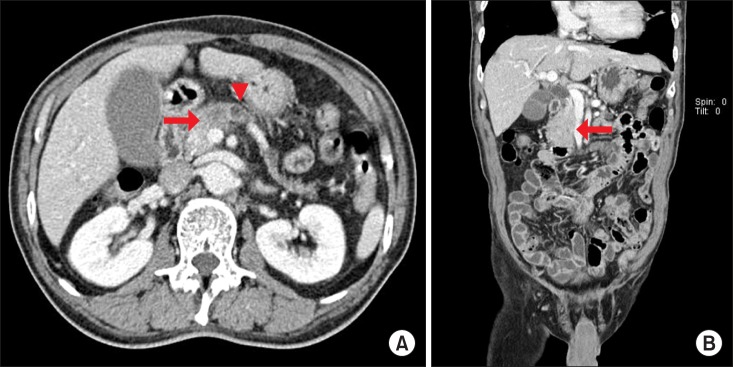

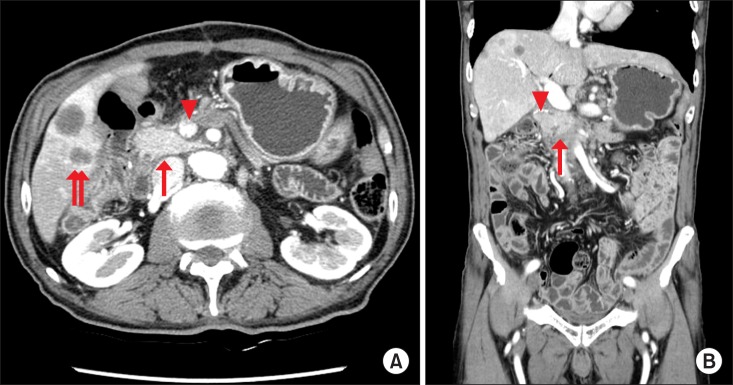

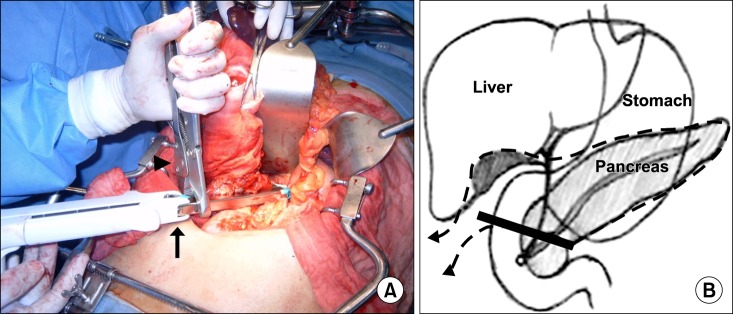

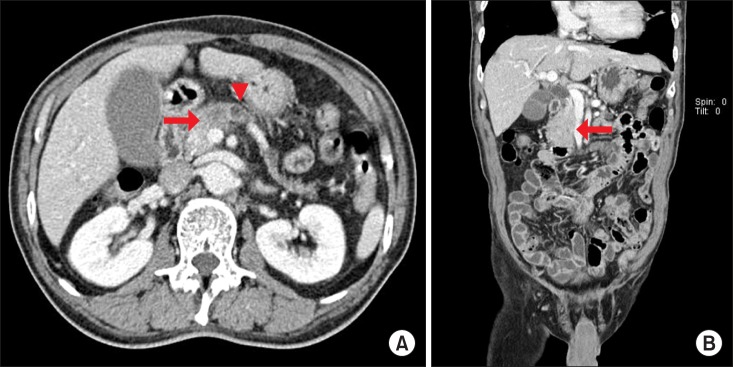

EDP was indicated for the following conditions: adenocarcinoma in the neck of the pancreas, with distal pancreatic atrophy, and no extension or invasion of the ampulla of Vater and the uncinate process. Pancreatic atrophy was defined when the ratio of the diameter of the main pancreatic duct to the width of the pancreatic parenchyma, measured at the body of the pancreas anterior to the aorta, was larger than 0.5 on computed tomography (

Fig. 1).

3

| Fig. 1Preoperative computed tomography of a representative patient. (A) Pancreatic neck cancer (arrow) with distal pancreatic atrophy shows dilated pancreatic duct (arrow head). (B) The uncinate process of the pancreas is intact (arrow).

|

Operative procedures

Patient preparation and dissection were similar to that in routine pylorus-preserving PD, until the common hepatic duct and the first duodenal portion were cut, respectively, and the stomach was retracted cephalad to expose the whole pancreas. The distal pancreas and spleen were dissected from the retroperitoneum, along with the splenic vessels, and the insertion of the splenic vein into the superior mesenteric vein was identified. When suspicious tumor invasion or adhesion was found in this area, blunt dissection was performed to detach the specimen from the superior mesenteric vein. The splenic vein was cut and the stump was closed using a 4-0 non-absorbable monofilament continuous running suture. After the specimen was mobilized and draped using a gauze tape, the only remaining structure included the second duodenal portion and the pancreatic head, which was isolated and ready to be cut.

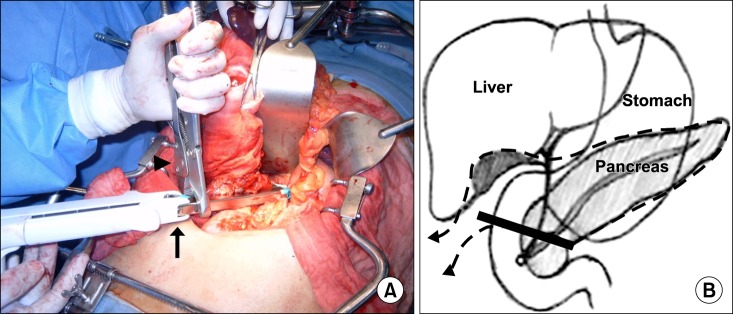

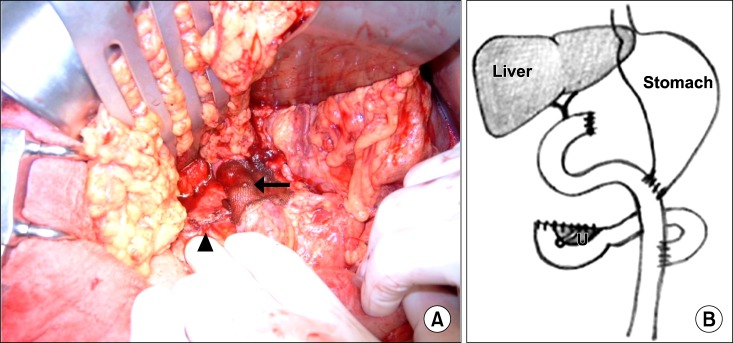

A linear stapling device (PROXIMATE® TCT 10, ETHICON ENDO-SURGERY, LLC, Guaynabo, Puerto Rico, 00969, USA) with a green cartridge was used to perform

en bloc resection of the distal pancreas, first duodenal portion, and distal common bile duct. When it was difficult to close the jaws of the linear stapler due to the bulk of the target organs, vise-grip locking pliers were applied to force the jaws together (

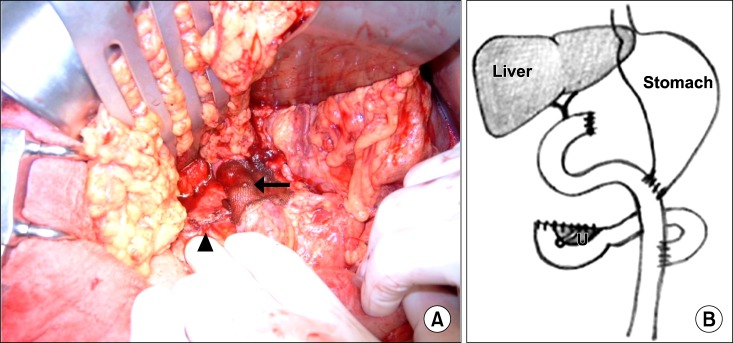

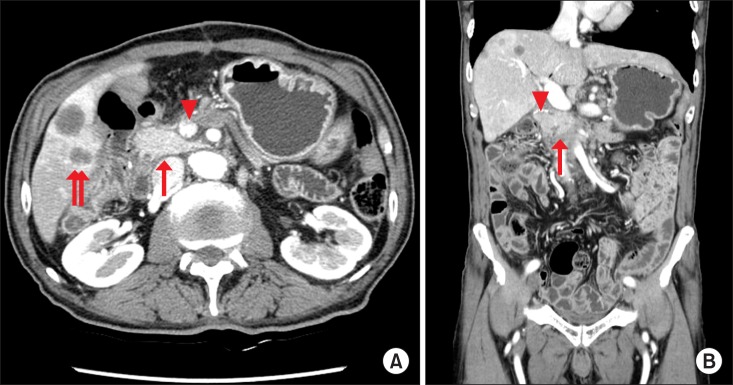

Fig. 2). The resected margins of the pancreatic head, common hepatic duct, and duodenum were sent to pathology for frozen section evaluation. After the resection, the invaded portion of the portal vein or superior mesenteric vein was resected and reconstructed using an artificial graft in a separate procedure (

Fig. 3A). Gastrointestinal continuity was restored by Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy, gastro- or duodenojejunostomy, and jejunojejunostomy (

Fig. 3B).

| Fig. 2Operative procedures. (A) A linear stapling device (arrow) and vise-grip locking pliers (arrowhead) are applied to resect the specimen en bloc. (B) Schematic diagram showing the resection line (dotted), along with the stapler line (solid).

|

| Fig. 3Operative procedures. (A) Operative field after resection. Portal vein is reconstructed using an artificial graft, beneath the hemostatic mesh (arrow). Note that the stapler line is visible (arrowhead). (B) Schematic diagram after gastrointestinal reconstruction of the uncinate process of the remnant pancreas.

|

The main outcomes of this study included postoperative pancreatic fistula (according to the ISGPF definition);

4 endocrine insufficiency, as indicated by daily serum glucose fluctuation (ΔG) and insulin requirements;

5 and exocrine insufficiency, as indicated by steatorrhea.

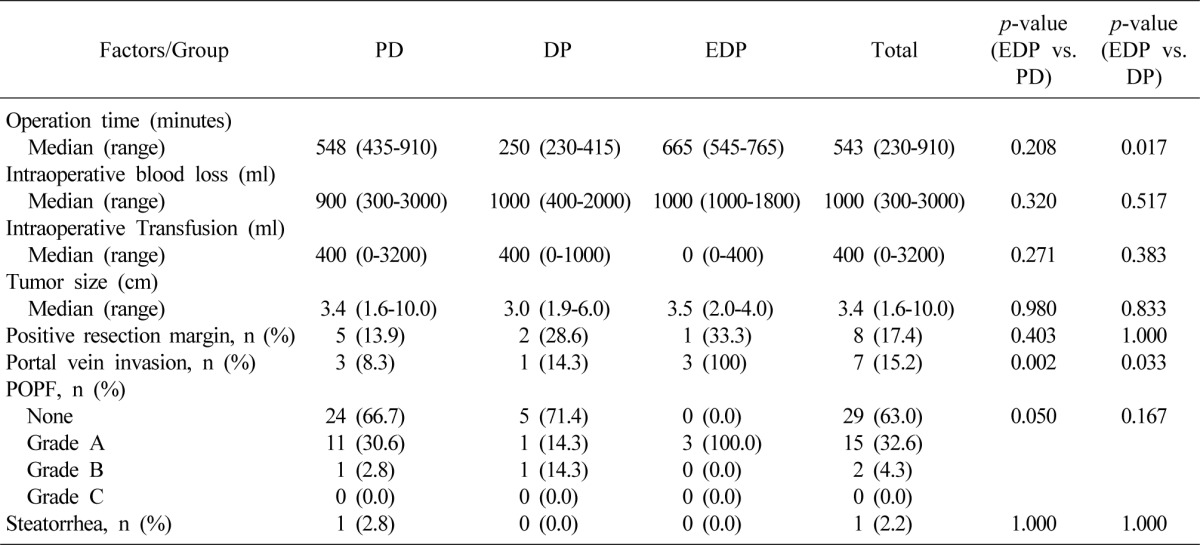

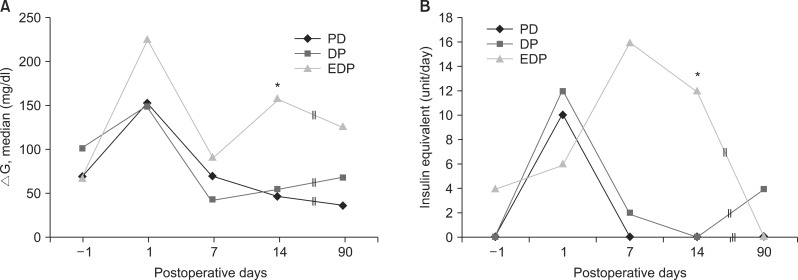

6 The integrity of the uncinate process of the remnant pancreas was also assessed on follow-up computed tomography scans (

Fig. 4).

| Fig. 4Follow-up computed tomography scan of the patient presented in Fig. 1 at 4 months after surgery. (A) The remnant pancreas is well-preserved (arrow), with intact portal flow (arrow head), although the patient developed multiple liver metastases (double arrow). (B) Coronal view of the uncinate process of the preserved pancreas (arrow) with the stapler line (arrow head).

|

Indicator of glycemic control

ΔG was defined as the daily maximum serum glucose level minus the daily minimum serum glucose level (mg/dl). When the serum glucose level was stable enough so that only one sample was required, the difference between the sampled glucose level and the normal median value (90 mg/dl) was recorded as ΔG. ΔG was recorded one day before surgery, and then at 1, 7, 14, and 30 days postoperatively. When serum glucose was not sampled on the indicated day, the serum value nearest to that day was analyzed. The daily insulin requirements, defined as the amount of insulin equivalent required to adjust the serum glucose level within the normal range, were recorded at the same date as ΔG.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, Ver. 19 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Mann-Whitney test was used for comparing continuous variables between groups, and Fisher's exact test was used for comparing categorical variables between groups. Statistical significance was accepted at p<0.05.

Go to :

RESULTS

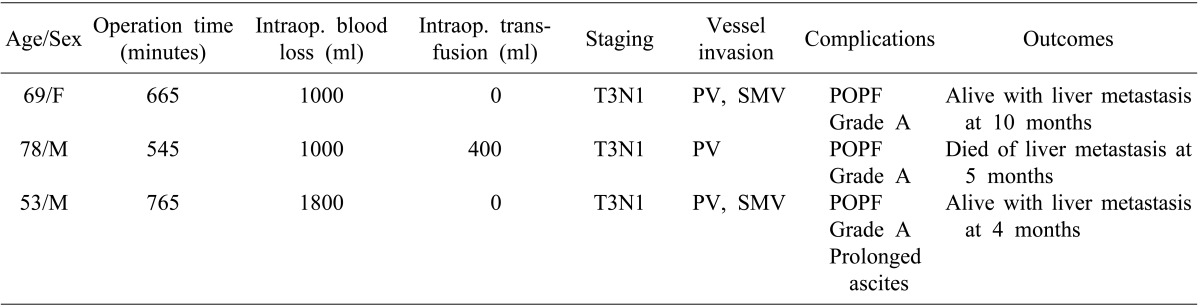

In the EDP group, the duration of the operation was between 9 and 13 hours, and the estimated blood loss was between 1000 and 1800 ml. Pathological staging was T3N1M0 in all three patients. The tumor had invaded the portal vein and the superior mesenteric vein in two patients, and in one patient, only the portal vein was invaded. Grade A pancreatic fistula developed in all of the cases, but all of these fistulae were controlled with supportive care. One patient required long-term drainage of ascites; however, steatorrhea did not occur in these patients. At the last follow-up, two patients were alive with liver metastasis at 4 and 10 months postoperatively, respectively, and one patient died of liver metastasis at 5 months postoperatively (

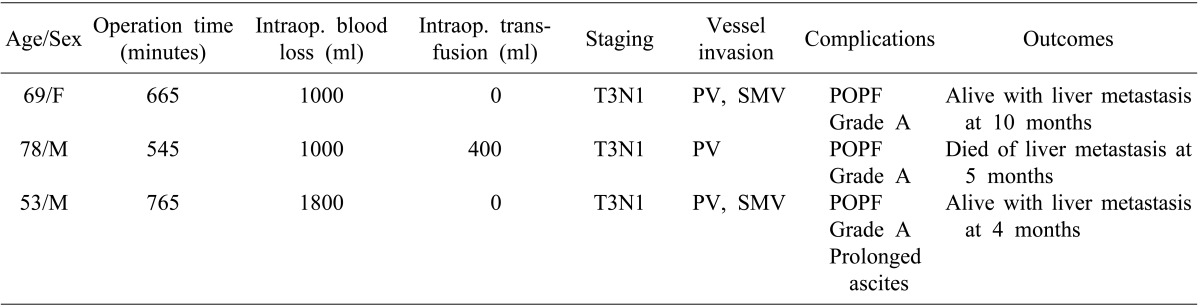

Table 2).

Table 2

Intraoperative and postoperative outcomes for patients who underwent extended distal pancreatectomy

Median operation time in all of the patients was 543 minutes; 665 minutes in patients who underwent EDP, 548 minutes in those who underwent PD, and 250 minutes in those who underwent DP. There was no statistically significant difference between the EDP and PD groups. However, the EDP group showed a significantly longer operation time than the DP group, probably because more time was needed for portal venous and gastrointestinal reconstruction in EDP. Otherwise, all of the three groups were comparable in terms of intraoperative blood loss, transfusion, tumor size, surgical radicality, and postoperative fistula formation. The proportion of patients with invasion of the portal or superior mesenteric vein was higher in the EDP group than in both the PD and DP groups (

Table 3).

Table 3

Comparison of intra- and postoperative results

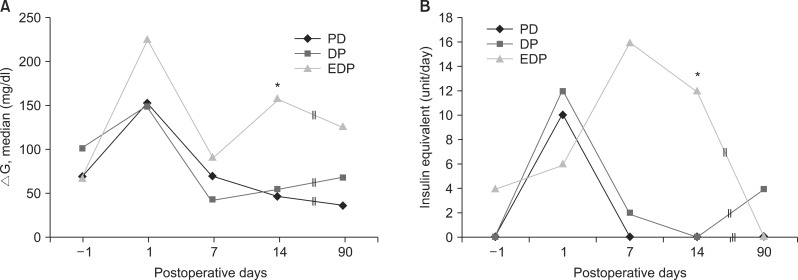

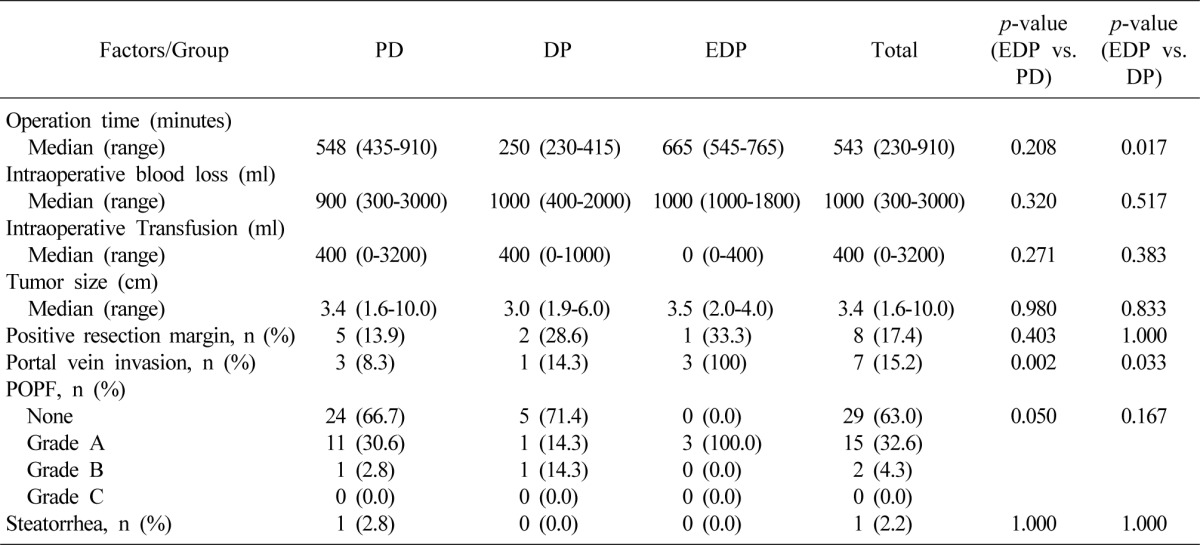

The ΔG values were not different between the groups, except that the EDP group showed a significantly larger blood glucose fluctuation (

Fig. 5A). Similarly, the EDP group required higher amount of insulin equivalent at 14 days postoperatively, which was not observed eventually at 3 months postoperatively (

Fig. 5B).

| Fig. 5(A) Preoperative and postoperative serum glucose profiles. ΔG, daily glucose fluctuation. (B) Daily requirements of insulin equivalent. *p<0.05.

|

Go to :

DISCUSSION

The standard operative procedures for pancreatic adenocarcinoma are PD and DP, depending on the tumor location.

2 Central pancreatectomy (medial, median, or middle segment pancreatectomy) has been proposed as an alternative treatment option for reducing the possibility of pancreatic functional impairment when tumors are located in the pancreatic neck and body. However, this treatment option has usually been used in benign diseases or low-grade malignancies.

7,

8

In patients with pancreatic neck cancer who present with jaundice, the preferred surgical procedure is PD. However, if the patient has atrophy of the distal pancreas, there are concerns regarding pancreatic endocrine and exocrine insufficiency after PD has been performed.

9,

10 In these cases, EDP, which preserves the uncinate process of the pancreas and the distal duodenum, can be an attractive option, provided that the tumor has not extended to the ampulla of Vater and the uncinate process.

EDP is technically feasible, and is considered relatively safe when compared to other standard pancreatic resections. Recently, stapling devices have been widely used in the resection of not only hollow viscera, but also solid organs such as pancreas and liver. However, a possible difficulty with the use of the stapler is the inability to close the jaws due to lack of gripping power. We have found that this difficulty can be overcome by using vise-grip pliers, which are usually available in the department of orthopedic surgery. This technique may also be useful in liver resection.

EDP can avoid pancreaticoenterostomy, which is the most compromised anastomosis of the pancreatic resection procedures.

11 We observed that all cases of EDP developed grade A postoperative pancreatic fistula, which resolved after conservative management, and had no significant clinical impact.

4 In literature, postoperative pancreatic fistula was documented in 10% to 15% of patients undergoing PD, and in 10% to 30% of patients undergoing DP. Different techniques of pancreaticoenteric anastomosis and pancreatic stump closure have not shown significant differences in the prevention of pancreatic fistula.

12 We assume that the rate of fistula development may decrease as compared to that in the standard DP on accumulation of more experience.

There was no steatorrhea, an indicator of exocrine insufficiency, in any of the patients who underwent EDP. In previous studies, postoperative steatorrhea was observed as a complication in 25.6% to 52.4% of patients undergoing PD.

10,

13,

14 Therefore, it is likely that EDP is at least as effective as PD in preventing postoperative pancreatic exocrine insufficiency.

In the previous studies on glylcemic control after pancreatic resection, HbA1c or fasting blood sugar (FBS), and 2-hour postprandial blood glucose (PP2) were used as the indicators of glycemic control.

10,

15,

16 However, HbA1c does not reflect the acute trend of blood glucose variations, and there are many patients whose FBS and PP2 were not measured pre- and postoperatively. Therefore, we chose ΔG as an indicator of glycemic control. We were unable to demonstrate that patients who underwent EDP had better glycemic control, although our results demonstrated that glucose profiles after EDP were comparable to those after PD or DP.

In conclusion, although the present study was limited by the number of cases in showing meaningful statistical significance, and the prognosis of advanced pancreatic neck adenocarcinoma is still dismal, EDP was technically feasible and safe, and can be a valid treatment option especially when there is atrophy of the distal pancreas. Further studies including more number of cases are warranted, and technical refinements are needed to improve patient survival.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download