Abstract

Systemic capillary leak syndrome (SCLS), also called Clarkson's disease is rare and life-threatening disorder of unknown etiology, which is a characteristic triad of hypovolemic shock, hemoconcentration, and hypoalbuminemia. Unexplained capillary leakage from the intravascular to the interstitial space, which has been estimated up to 70% of the intravascular volume, is the proposed mechanism. Because the pathogenesis is unknown, it is diagnosed clinically after exclusion of other diseases that cause systemic capillary leak and no efficacious pharmacological treatment has been clearly established. The mortality rate ranges from 30% to 76%. In Korea, four cases of SCLS (5 cases in adult and 1 case in child) were reported by 2012. We describe a case of severe SCLS that suddenly occurred and rapidly progressed during pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy and review the literature.

Go to :

Systemic capillary leak syndrome (SCLS) which is also called Clarkson's disease is rare and life-threatening disorder of unknown etiology.1 Unexplained capillary leakage from the intravascular to the interstitial space, which has been estimated up to 70% of the intravascular volume, is the proposed mechanism and a transient dysfunction of the endothelium is accepted as the most suspected cause and triggering factor.2 In consequence of capillary leakage, SCLS has a characteristic triad of hypovolemic shock, hemoconcentration, and hypoalbuminemia. Because the pathogenesis is unknown, it is diagnosed clinically after exclusion of other diseases that cause systemic capillary leak. As the underlying mechanism is unknown, no efficacious pharmacological treatment has been clearly established. The mortality rate ranges from 30% to 76%.3 We describe a case of severe SCLS that suddenly occurred and rapidly progressed during pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPD) and review the literature.

Go to :

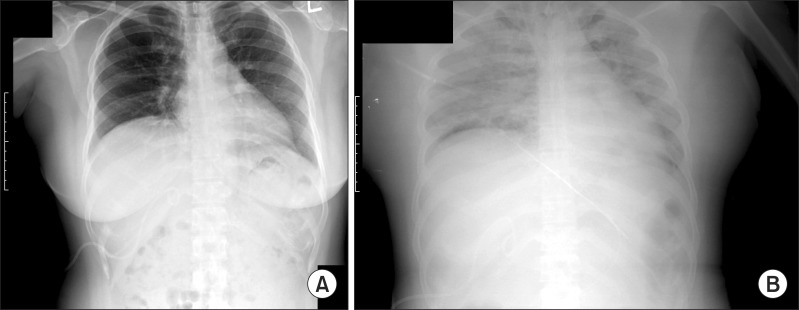

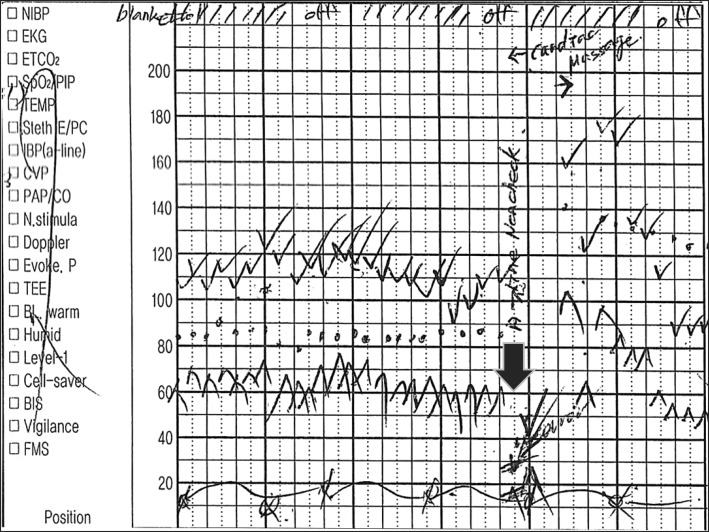

A 41-year-old, well-controlled type II diabetic woman (153 cm in height and 68 Kg in weight) was referred to the surgery department to have an elective pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPD) for the distal bile duct cancer. Her preoperative blood pressure, pulse rate, and body temperature were 130/90 mmHg, 70/min, and 36.5℃, respectively. Laboratory studies showed leukocyte count 9,400 /ul, hemoglobin(Hb) 13.5 g/dl, hematocrit (Hct) 41.0%, C-reactive protein (CRP) 0.36 mg/dl, serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 124 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 179 IU/L, total bilirubin 3.8 mg/dl, alkaline phosphatase 1,313 IU/L, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase 1,218 IU/L, cholesterol 328 mg/dl, and CA19-9 246 U/ml. Urine analysis and urine pregnant test were negative. Her initial total bilirubin (6.5 mg/dl) has been decreased to 3.8 mg/dl after the percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) catheter was placed. A chest radiograph revealed no significant findings (Fig. 1A). An electrocardiogram and echocardiogram did not show any abnormal signs. Two days prior to surgery, the patient's body temperature had increased to 38.7℃, with normal range of white cell count and C-reactive protein, and the patient had no subjective symptoms. The body temperature was normalized soon without medication. On the operation day, pentothal sodium and vecuronium were administered to facilitate a tracheal intubation, and the anesthesia was maintained with nitrous oxide and desflurane in oxygen. At this point, the arterial blood pressure was 140/80 mmHg, heart rate, 80 bpm, central venous pressure (CVP) 10 mmHg and the oxygen saturation 100%, bispectral index (BIS) 45-50. About three hours forty minutes after the operation started, when the surgical specimen was removed out and the intestinal anastomosis was about to start, the end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) curve was abruptly reduced and then, disappeared. At the same time, her arterial blood pressure, CVP, and oxygen saturation abruptly decreased to 40/25 mmHg, 3 mmHg, and 88% respectively (Fig. 2) and BIS value was not checked without sudden blood loss or unusual conditions. There was no evidence of airway obstruction. Intravenous fluid (1,000 ml of crystalloid and 3,000 ml of colloid) were rapidly infused and cardiopulmonary resuscitation including cardiac massage, ephedrine, phenylephrine, epinephrine, and atropine were conducted for 20 minutes. After that, her vital signs were recovered to 130/80 mmHg but, BIS value was not. Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) demonstrated normal heart function. Her vital signs were stable until the surgery finished.

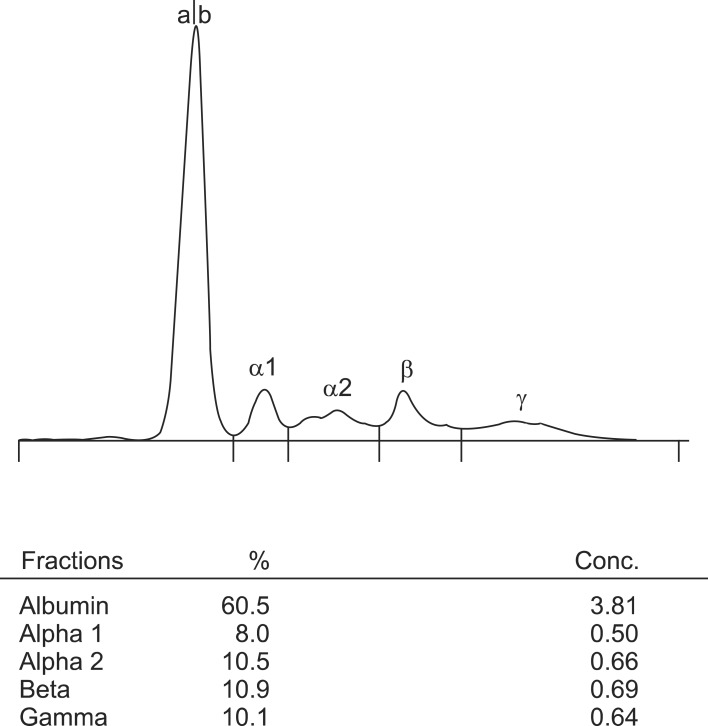

The patient was taken to the surgical intensive care unit and a chest radiograph just after the surgery revealed diffuse bilateral infiltrates, without cardiomegaly (Fig. 1B). Mechanical ventilation with pressure support mode was applied. Immediate postoperative laboratory studies showed hemoglobin 18.1 g/dl, hematocrit 51.9%, leukocyte count 23,600/ul, total protein 2.8 g/dl, and albumin 1.1 g/dl. Critical medicine doctor presumptively diagnosed systemic capillary leak syndrome (SCLS) and 20% albumin, hydrocortisone 300 mg/day and theophylline 400 mg/day, human immune globulin G (IVIG) 1 g/kg/day were immediately administered, intravenously. On the postoperative day 3, total protein/albumin and Hb/Hct levels turned to 5.6/3.3 g/dl, 11.8 g/dl/35.1%, respectively, but creatine phosphokinase (CPK) was elevated to 1,897 U/L (normal range: 50-250 U/L), procalcinotnin 14 ng/ml, and CRP 21.53 mg/dl. Immunoglobulin quantification study showed that the complements, C3 and 4 were normal, the immunoglobulin (Ig) G 406.5 mg/dl (normal range: 694-1,618) and IgM 40 mg/dl (normal range: 60-263) were decreased, and however, Ig E was 681.13 IU/ml (normal range: <120), which was elevated. Ig A was within the normal range. Serum electrophoresis showed that total protein was within normal limit (6.3 g/dl) and alpha-1-globulin fraction was increased, and there was no abnormal band (Fig. 3). About the time when pulmonary edema has improved considerably, the patient showed abnormal eye ball movements as well as the generalized seizure on the postoperative day 7. A portable electroencephalography (EEG) was taken, which showed suggestive of severe diffuse cerebral dysfunction. Subsequently performed enhanced computed tomography scan and magnetic resonance imaging of the head showed diffuse brain atrophy and ischemic change in the periventricular deep white matter. In the meantime, the final report of surgical pathology was an adenocarcinoma arisen from intraductal papillary neoplasm of the distal common bile duct with pancreatic, perineural invasions, but clear resection margins. Two out of 28 nodes were metastatic regional lymph nodes. On the postoperative day 14, her pulmonary condition has fully improved; however, unfortunately, she is still in bed more than one year because of brain injury.

Go to :

Idiopathic systemic capillary leak syndrome (SCLS or ICLS) is a rare and severe disorder, first described by Clarkson et al in 1960.1 This syndrome presents with a characteristic triad of hypotension, hemoconcentration, and hypoalbuminemia.1 The etiologies as well as the triggering factors, remain unknown. During an episode, up to 70% of the plasma rapidly shifts from the intravascular to the interstitial space, resulting in hypovolemic shock. The cause of these episodes of marked capillary leakage is not known. Despite many reports have been proposing mechanisms involving biochemical substances or cells which might act on the capillaries to cause their leakiness, no consistent alteration has been proven histologically.2 Several reports strongly support an immunologic basis for this syndrome. Monoclonal immunoglobulin could be responsible for endothelial damage and capillary hyperpermeability.3,4,5

SCLS is diagnosed clinically after exclusion of wide variety of diseases that cause systemic capillary leak such as infections, hereditary angioedema, chemotherapy, malignancy, drugs, anesthesia, and surgery with laboratory evidence of the plasma leak.4,6,7,8 Hemoconcentration and hypoalbuminemia are the cornerstones of the diagnosis. Dhir et al. has reported laboratory features of SCLS, that hematocrit was recorded to be high, 63.5±8.65%; serum albumin was mentioned to be low to 1.67±0.66 g/dl. Complement levels are usually normal.2 The role of monoclonal protein found in the sera of many of the cases remains uncertain.3 Clinical Features of SCLS are that shock is a defining feature of this illness. The condition often mimics septic shock and has prodromal symptoms such as flu-like symptoms including myalgia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting. Non-pitting edema, effusion or tissue edema included bilateral pleural effusions, pericardial effusion or tamponade, cerebral edema, epiglottic edema and even macular edema leading to blindness.2,3,9

Because of hypovolemic shock, oliguria or anuria or deranged renal function tests, frank renal failure after resolution of acute episode were few.10 It has been reported that the clinical features of an acute episode of SCLS consist of two phases: The initial capillary leak phase may last from 1 to 4 days and is essentially a phase of acute hypovolemia. In the recruitment phase, intravascular overload may occur easily and result in acute pulmonary edema and is characterized by unexplained recurrent episodes of severe capillary hyperpermeability, generalized edema, hemoconcentration and reduced serum albumin.5 Because the etiology is unknown and no efficacious pharmacological treatment has been clearly established, the treatment of SCLS is empiric. Intensive care unit and careful monitoring of fluid volume are essential in SCLS. In acute stage, intravenous fluids such as crystalloids and colloids, inotropes and mechanical ventilation should be given but very aggressive fluid infusion in the leak phase carries a risk of causing pulmonary edema in the recovery phase. Respiratory failure due to pulmonary and upper airway edema was successfully treated with massive infusion of human plasma or fresh frozen plasma, mechanical ventilation with PEEP. In chronic stage, theophylline, terbutalinein combination or alone, intravenous steroid, calcium channel blockers, IVIG, leukotriene modifiers, and plasmapheresis are recommended.11,12

The prognosis of SCLS is uncertain. Recurrent attacks are common and the condition is often fatal. The cause of death in the initial phase is circulatory collapse. The mortality among SCLS patients has been reported to be as high as 18-36%. The mortality rate ranges from 30% to 76%. In contrast to the poor survival noted previously, 10-year survival rate estimates greater than 70% which has shown an increasing trend since this syndrome was first recognized.2,3

In conclusion, the present case typically matched with clinical findings of SCLS occurred during elective PPPD. Our patient was survived from episodes of serious hypovolemia after initiation of proper treatment, but unfortunately she was injured in the brain. We still wonder if occult infection, because she had a self-limiting fever and surgical procedures including aggressive lymph node dissection could trigger this situation. We should be aware that sudden and profound SCLS is a potentially lethal condition and can occur anytime even during elective surgery although the patient's condition is well controlled.

Go to :

References

1. Clarkson B, Thompson D, Horwith M, et al. Cyclical edema and shock due to increased capillary permeability. Am J Med. 1960; 29:193–216. PMID: 13693909.

2. Dhir V, Arya V, Malav IC, et al. Idiopathic systemic capillary leak syndrome (SCLS): case report and systematic review of cases reported in the last 16 years. Intern Med. 2007; 46:899–904. PMID: 17575386.

3. Druey KM, Greipp PR. Narrative review: the systemic capillary leak syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2010; 153:90–98. PMID: 20643990.

4. Lee TY, Chung YM, Kang HG, et al. A case of systemic capillary leak syndrome in a child. J Korean Pediatr Soc. 2002; 45:1298–1301.

5. Chihara R, Nakamoto H, Arima H, et al. Systemic capillary leak syndrome. Intern Med. 2002; 41:953–956. PMID: 12487166.

6. Kanda K, Sari A, Nagai K, et al. Postpartum capillary leak syndrome. A case report. Crit Care Med. 1980; 8:661–662. PMID: 7428393.

7. Kim YM, Seok HJ, Kim SH, et al. A case of systemic capillary leak syndrome following upper respiratory tract infection. Korean J Nephrol. 2003; 22:251–256.

8. Ohmi S, Takei T, Habuka K, et al. Acute pulmonary capillary leak syndrome during elective surgery under general anesthesia. J Anesth. 2008; 22:77–80. PMID: 18306021.

9. Bertorini TE, Gelfand MS, O'Brien TF. Encephalopathy due to capillary leak syndrome. South Med J. 1997; 90:1060–1062. PMID: 9347824.

10. Baek SH, Shin N, Kim HJ, et al. A case of chronic renal failure associated with systemic capillary leak syndrome. Yeungnam Univ J Med. 2012; 29:145–149.

11. Lambert M, Launay D, Hachulla E, et al. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulins dramatically reverse systemic capillary leak syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2008; 36:2184–2187. PMID: 18552679.

12. Cho EJ, Cha IH, Yoon KC, et al. Recurrent systemic capillary leak syndrome responding to the corticosteroid therapy. Korean J Nephrol. 2010; 29:513–518.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download