INTRODUCTION

Classical pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) and pylorus-preserving PD (PPPD) are complex procedures for periampullary disease. Because of the complexity as well as the leak-prone nature of pancreatic anastomoses, this procedure was associated with significantly high incidences of morbidity and mortality. Recent improvements in pancreatic surgery have led to a decrease in the mortality rates, with the rates moving toward less than 5% in high-volume centers,

1,

23 and operative morbidity approaching 30% to 40%,

4,

5,

6 including the operative morbidities of intra-abdominal abscess, sepsis, pancreatic fistula, and delayed gastric emptying. Recent studies have shown that PPPD can be performed quite safely, especially in high volume centers.

5,

7

Critical pathways (CP) are structured multidisciplinary care plans that detail the essential steps in the care of patients with a specific clinical problem and describe the expected patient progress.

8 CP describes the tasks to be carried out in time sequences and the discipline involved in completing the tasks. CP may involve surgeons, nurses, other health care professionals, patients, and families.

The implementation of CP was performed in many categories of diseases, resulting in improved efficacy, and reduction in the length of the hospital stay as well as costs.

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14 These CPs have been one of the key tools used to achieve excellent outcomes in high-quality, high-volume centers. Initially, CP was used in relatively simple procedures, but recently, CP has begun to be employed in complex procedures. But the evidence to support their use for complex procedures is limited, especially for complex pancreatic surgery.

9,

13 This study was intended to evaluate the impact of clinical pathway implementation for PPPD patients.

METHODS

Patient selection

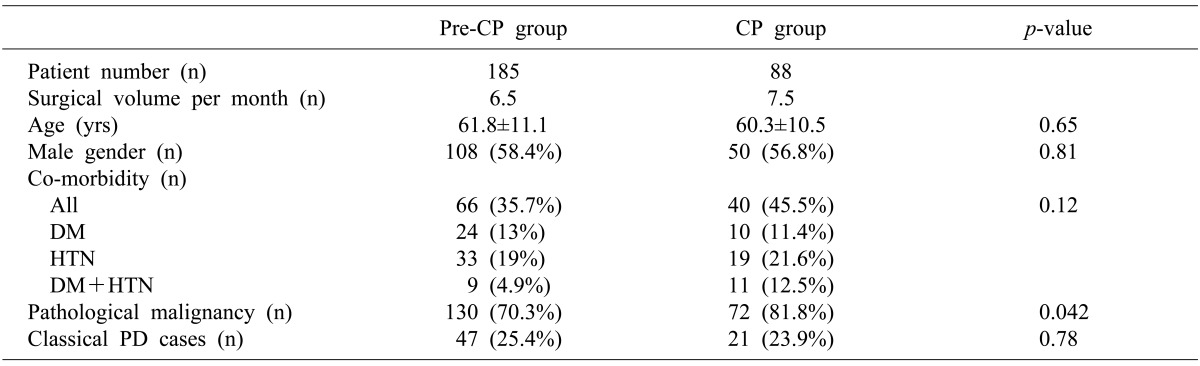

The study population was patients undergoing PD or PPPD. Between January 2005 and December 2010, 273 patients underwent PPPD or PD at our institution by a single surgeon (SC Kim). A critical pathway for PD was implemented from January 2009. Thus, 185 patients who underwent surgery during a 48-month period before the implementation of CP were allocated as the pre-CP group (control group), and 88 patients who underwent surgery during a 24-month period after CP implementation became the CP group (the study group). Patients who received additional vascular resection-anastomoses were included as they were treated according to CP. To avoid bias, the patients undergoing laparoscopic PPPD were excluded because they usually had a shorter hospital stay compared with those who received an open procedure. Peri- and post-operative parameters were analyzed retrospectively through a medical record review. This retrospective study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of our institution.

Component of the critical pathway

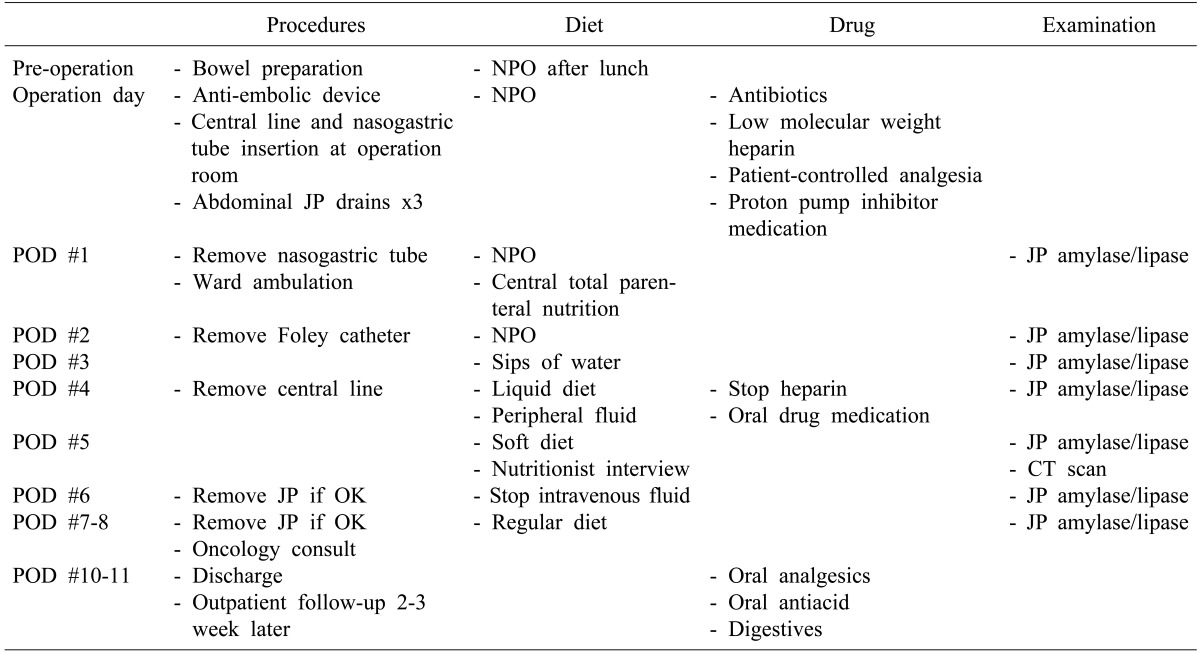

This CP protocol for PD and PPPD (

Table 1) was developed by one surgeon (SC Kim) and a clinical nurse practitioner. The CP was applied to patients if there was no clinically significant postoperative complication after the surgery. Templates were generated for a set-order system in the hospital's electric medical record (EMR) system.

CP application began at admission for the operation, with education of the patient and families using a guide in booklet form which had been developed for PD/PPPD patients. Specific aspects of CP included the management of the abdominal drains and tubes, medications, diet, and a special study for patients.

Details of the CP for PD and PPPD are as follows (

Table 1): on the day before surgery, all patients were ordered to fast after lunch, as well undergo a mild bowel preparation. In the operation room, a sequential compression device was applied and continued till the morning of the second postoperative day. Subcutaneous low-molecular weight heparin was used for 4 days from the operation day for prevention of deep vein thrombosis. All patients received an intravenous infusion of proton pump inhibitors and prophylactic antibiotics. For postoperative pain control, a patient-controlled analgesia device and additional on-demand narcotics or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug were used. At the first postoperative day, patients were encouraged to have ward ambulation and the nasogastric tube was removed. Patients started sips of water on the third postoperative day, with reduction of intravenous fluids, and a liquid diet was commenced on the fourth day, and a soft diet on the fifth day, with pancreatic enzyme supplementation. In most patients, initiation of a regular diet began around the seventh postoperative day. An interview with a nutritionist after a soft diet was started was included in this CP. Amylase and lipase levels of the fluid in the abdominal drains were measured every day, and postoperative abdomen computed tomography (CT) was performed on the fifth day. The abdominal drains were removed on the eighth postoperative day if no clinically significant pancreatic fistula or fluid collection was identified. Discharge medications included an antacid, analgesics, and a pancreatic enzyme supplement in addition to the baseline medications. A follow-up visit was scheduled 2-3 weeks after discharge with a visit to the concurrent oncologist clinic scheduled on the same day.

Surgical procedure and definition of complications

The procedures on all patients were performed by a single surgeon. When doing the PPPD, the pancreaticojejunostomy was performed in end-to-side fashion using the duct-to-mucosa technique. Pancreaticogastrostomy was not performed at all. Braun anastomosis (side-to-side jejunojejunostomy) was routinely performed.

The complications after surgery were graded by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definitions.

15,

16,

17 Clinically significant complications were defined as delayed gastric emptying (DGE) grade B or C, post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPF) grade B or C, postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) grade B or C, wound infection or other complications which needed an intervention. All of these can influence patient outcomes or the length of hospital stay.

Nutritional state evaluation

Mini Nutrition Assessment (MNA) has been commonly used for grading the nutritional status and the risk of malnutrition in hospitalized patients.

18,

19 Key components of the MNA are the body weight, serum protein, and lymphocyte count.

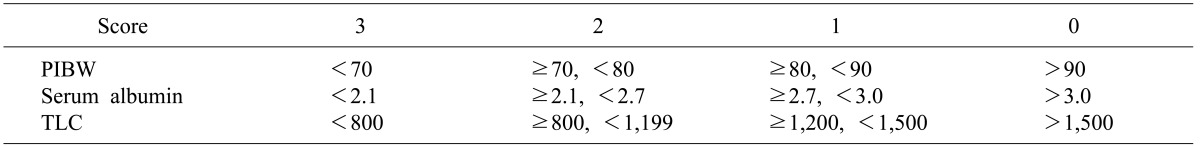

20 To perform the nutritional status assessment more effectively, we developed a simplified MNA (sMNA). Our sMNA comprised of 3 components including the weight as a percentage of the ideal body weight, serum albumin concentration, and a total lymphocyte count. We calculated a score for each item according to the definition, and then determined the nutritional status by summation (

Table 2). The nutritional status was determined to be adequate if the summed score ranged from 0-3, level 1 if the score ranged from 4-6, and level 2 if the score ranged from 7-9.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test, and when applicable, Fisher's exact test. Continuous variables were analyzed using Student's t-test. Numeric variables were expressed as the mean±standard deviation or as a percentage. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS package (version18.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL).

DISCUSSION

CPs are care plans that detail the essential steps in the care of patients with a specific clinical problem.

8 Although their use in clinical medicine was initially focused on use by nurses and other non-physician medical staff, physician-driven and -directed clinical pathways have gained popularity over the past decades as an effort to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of clinical medical services.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the implementation of CP decreases the length of hospital stay, total costs, or both, following various gastrointestinal surgical procedures.

11,

12 More recently, even in the case of more complex surgeries such as pancreas head resection, and distal pancreatectomy, shorter hospital stays and reduced hospital charges were observed after implementation of CP.

13,

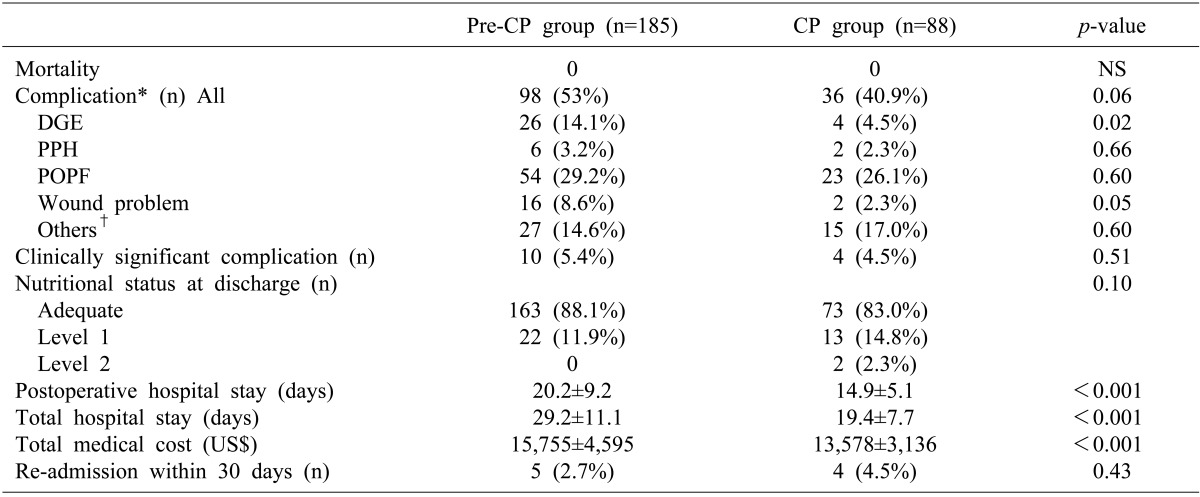

14 The results of this study also demonstrated that the hospital stay and costs were significantly reduced after implementation of CP in 88 patients who underwent PPPD or PD, with patients showing maintenance or improvement of clinical outcomes.

When considering the effect of CP on postoperative hospital stay, the early start of an oral diet might contribute to the shortening of the postoperative hospital stay, but other factors must be related to this effect. In this study, CP implementation advanced the start of an oral diet by 3.5 days, but hospital discharge was increased by 5.3 days, which was a difference of 1.8 days.

Although there is no doubt that significant indirect costs to both the patients and society exist in the patient population undergoing PD or PPPD, a comparative assessment of the medical costs was confined to the direct hospital costs in this study because of the limitations of the study's retrospective design. It is important to note that many parts of the medical costs occurring during the perioperative period were incorporated and rather fixed (i.e., anesthesia management, specific operative treatment, and pathologic examination), and thus, these portions were not influenced by CP implementation. It is possible to hypothesize that the reduced costs observed in CP patients were not primarily due to the CP implementation, but were simply a consequence of the substantial difference between the room cost and boarding costs, including the special medical staff care fee. The results of this study revealed that the total cost difference before and after CP implementation was greater than the difference that originated from room and board costs. Such a remarkable reduction of the total medical costs seems to be associated with integrated efforts toward maximizing cost-effectiveness in every part of perioperative medical care, without sacrificing patient safety.

The fact that a patient is "on the pathway" may result in more of a push from health care providers for the patient to recover, unrelated to any specific component of the pathway, the so-called Hawthorne effect.

21 We also think that this Hawthorne effect might, at least in part, be responsible for some of the differences observed in this study. However, considering the relatively long length of the study period of 2 years, we do not think that a temporary phenomenon such as the Hawthorne effect was one of the main components of the enhanced cost-effectiveness.

There are several important points to emphasize when implementing CP as follows: CP leads to standardization of medical care; all persons engaged in the treatment including charge doctors, nurses, paramedical and the patients themselves share the same knowledge; patients can anticipate the recovery pathways; it leads to maximal utilization of medical resources; it serves as a care map for doctors' training; and it may provide baseline information for improving the CP protocol.

We do not think that our current CP protocol is sufficiently cost-effective and patient safety-oriented. If some unexpected complication happens, we are ready to revise the CP protocol toward maximizing patient safety. The results of this study revealed that CP as a fast-tracking protocol plays an important role in patient care, in maximizing resources, and in resident and fellow training. Therefore, without even mentioning the improvement in the quality of medical care, implementation of CP is a means of providing cost effective care and decreasing the use of hospital resources.

One non-negligible limitation of this study was that the study design included a historical control group. The surgeon's experience may have affected the complications, especially following complex surgery such as PD and PPPD, although the surgical volume was similar between the study group and control group (7.5 cases/month and 6.5 cases/month). Several studies have demonstrated the importance of the surgeon and institutional surgical volume in reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with PD. There are several other limitations regarding this study. There was no comparison data with other medical centers. In addition, the number of the study groups was rather small, thus increasing type II error. Finally, this study lacked a patient satisfaction survey.

In conclusion, despite the complexity of PD and PPPD procedures, the implementation of CP significantly reduced medical costs and enhanced resource utilization without any detrimental effects on the quality of patient care, and it even showed improved outcomes. These results support the idea that CP can be safely applied to complex surgical situations if reasonably developed CP protocols are established. Further investigation through multi-center high-volume studies is necessary to validate the actual impact of CP for PD and PPPD.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download