Abstract

The right-sided diaphragmatic rupture is often clinically occulted due to buffering effects of the liver and thus, erroneous diagnosis of such rupture may result in life-threatening conditions. A 44-year-old female who had a history of car accident in 2006 was admitted to our hospital for pleuritic pain. On the chest computed tomography, she was diagnosed with diaphragmatic rupture accompanied by herniation of hypertrophic left liver with complicated cholecystitis and we carried out cholecystectomy, reduction of the liver, pleural drainage, and primary closure of the diaphragm via thoracic approaches. Our case is presented in three unique aspects: herniation of left hemiliver, hypertrophic liver herniated up to the 4th rib level, and combination of complicated cholecystitis. Although the diagnosis of right-sided diaphragmatic rupture can be challenging for the surgeon, an early diagnosis can prevent further complications on the clinical presentation.

Although acute diaphragmatic rupture presents with symptoms like dyspnea, chest pain, abdominal pain, and vomiting, right-sided diaphragmatic rupture, owing to a buffering effect of the liver, remains clinically occult and only about 19% of patients reveal herniation of the intra-abdominal organs into the pleural cavity1,2 Therefore, without clinical suspicion of diaphragmatic ruptures, there were missed diagnosis results in respiratory distress, bowel obstruction, strangulation, or other septic conditions. Here, we present a rare case of traumatic diaphragmatic rupture with complicated cholecystitis, which was successfully treated via thoracic approach.

A 44-year-old female was referred to our hospital in January 2011 for further evaluations of pleuritic pain. She had a medical history of traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage and right rib fractures caused by a car accident in 2006 in which she remained symptom-free for 4 years. However, since early 2010, she suffered from intermittent right chest pains, febrile sensation, and dyspnea, which were relieved by left decubitus position; ten days prior to admission, her symptoms became more aggravated.

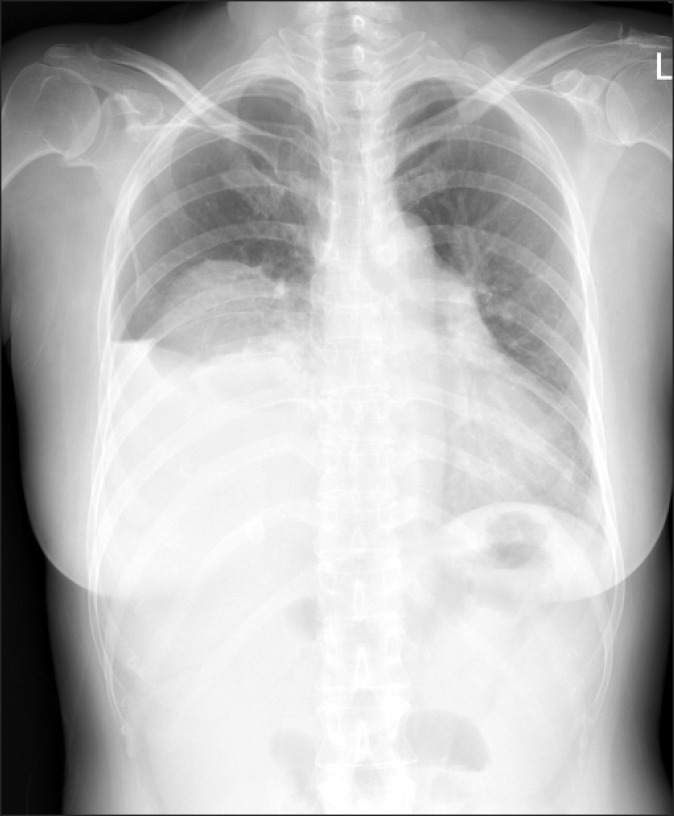

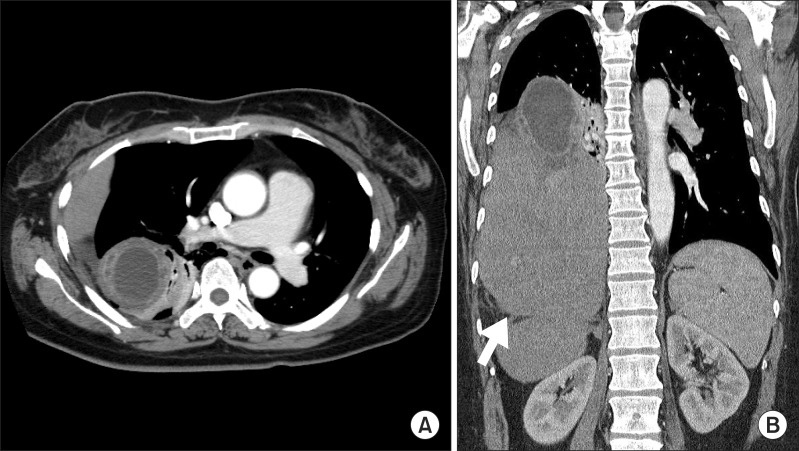

Chest radiography showed high positioning of the right hemi-diaphragm (Fig. 1). Chest computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated typical findings of diaphragmatic rupture, including diaphragmatic discontinuity with a diaphragmatic defect measuring 11 cm, waist-like constriction of abdominal viscera (the 'collar sign'), and herniation of abdominal organs into the thoracic cavity.3-5 Left hemiliver and a part of the anterior section of the right liver, which were flipped 90 degrees ventrally, were herniated in the right thorax and the liver volume of the intrathoracic portion was three times larger than that of the abdominal portion. Volumetric calculations of the intrathoraic and intra-abdominal portion, calculated by CT scan, were 1,480 and 484 cm3, respectively. In addition, impacted gallstone, gallbladder wall thickening, and pericholecystic abscesses were all observed (Fig. 2).

She was diagnosed with right-sided diaphragmatic rupture accompanied by hepatic hernia and complicated cholecystitis, and therefore, we decided to perform cholecystectomy, reduction of the liver, pleural drainage, and primary closure of the diaphragm via thoracic approach.

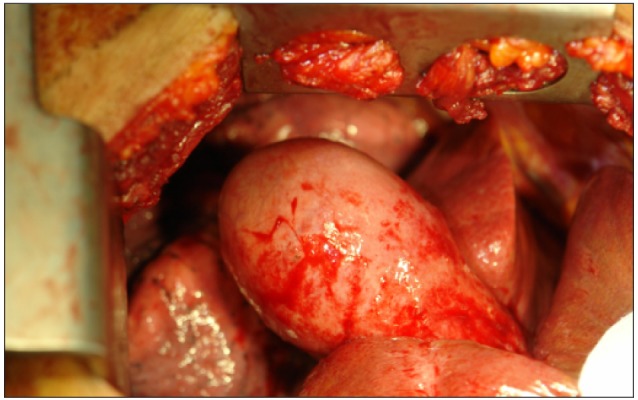

On the thoracotomy, herniated hypertrophic liver was caught in a ruptured diaphragmatic defect and there was distended gallbladder with edematous wall thickening (Fig. 3). Firstly, cholecystectomy was performed with great caution, followed by an additional lateral incision on the right edge of the diaphragmatic defect, which released incarceration and facilitated easy reduction of the liver into the abdominal cavity. The size of the diaphragmatic defect was 11 cm and the defect was repaired primarily with a non-absorbable interrupted suture. She showed excellent recovery postoperatively and was discharged from the hospital on the 9th day after surgery.

The cause of delayed presentation of diaphragmatic rupture is explained by a missed diagnosis in the acute phase and occult presentation of symptoms resulting in delayed detection. Particularly in the case of right-sided diaphragmatic rupture, the chest radiography only allowed diagnosis of 17% and helical CT showed a sensitivity of 50%.6,7 Also, the plugging effect of the liver over the defect caused patients to remain silent. However, an increase of abdominal pressure may later result in the enlargement of an overlooked small defect and lead to the migration of abdominal organs into the thoracic cavity.

Many literature studies have reported on delayed diaphragmatic rupture; however, our case involves three unique aspects. First, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports concerning complicated cholecystitis with diaphragmatic rupture. In general, a prosthetic patch is recommended for large defects. However, under contaminated or dirty conditions, like infected bile spillage from the gallbladder, the application of a prosthetic patch is limited in order to avoid postoperative infections. Therefore, we performed cholecystectomy with caution in order to not perforate the gallbladder. Second, most of the herniated liver was left hemiliver, as contrary to other literature reports.8 One possible explanation for this finding is that a herniated abdominal organ is determined according to the site of an injured diaphragm. When the anteromedial portion of the right hemi-diaphragm is injured, the left sided visceral liver can be the main abdominal viscera of herniation. Third, hypertrophic liver, which was flipped ventrally, was herniated up to the 4th rib level of the right thoracic cavity. The reason for hypertrophy of the liver is not clear; however, we suppose that inadequate blood flow to the posterior section of the liver caused by hepatic pedicle torsion may induce compensatory hypertrophy of an unaffected liver.

Initially, we contemplated the use of a prosthetic patch for large defects and additional abdominal incision for colonic mobilizations to obtain the optimal position of the hypertrophic liver. Although, fortunately, there was no need for a prosthetic patch or colonic mobilization in our case, technical modifications may be needed for complicated cases.

In conclusion, we experienced a rare case of right-sided diaphragmatic rupture with hypertrophic liver and complicated cholecystitis, which occurred 5 years after a car accident, and we recommend that early diagnosis can prevent a more complicated clinical presentation.

References

1. Wirbel RJ, Mutschler W. Blunt rupture of the right hemi-diaphragm with complete dislocation of the right hepatic lobe: report of a case. Surg Today. 1998; 28:850–852. PMID: 9719010.

2. Boulanger BR, Milzman DP, Rosati C, et al. A comparison of right and left blunt traumatic diaphragmatic rupture. J Trauma. 1993; 35:255–260. PMID: 8355305.

3. Heiberg E, Wolverson MK, Hurd RN, et al. CT recognition of traumatic rupture of the diaphragm. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1980; 135:369–372. PMID: 6773345.

4. Demos TC, Solomon C, Posniak HV, et al. Computed tomography in traumatic defects of the diaphragm. Clin Imaging. 1989; 13:62–67. PMID: 2743195.

5. Holland DG, Quint LE. Traumatic rupture of the diaphragm without visceral herniation: CT diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991; 157:17–18. PMID: 2048513.

6. Gelman R, Mirvis SE, Gens D. Diaphragmatic rupture due to blunt trauma: sensitivity of plain chest radiographs. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991; 156:51–57. PMID: 1898570.

7. Killeen KL, Mirvis SE, Shanmuganathan K. Helical CT of diaphragmatic rupture caused by blunt trauma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999; 173:1611–1616. PMID: 10584809.

8. Rashid F, Chakrabarty MM, Singh R, et al. A review on delayed presentation of diaphragmatic rupture. World J Emerg Surg. 2009; 4:32. PMID: 19698091.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download