Abstract

A 67-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital under suspicion of a hepatic tumor, which had been previously diagnosed to be an adenocarcinoma by fine needle aspiration. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging revealed a large tumor measuring 9 cm in diameter in Couinaud's hepatic segments 4, 5, and 8. We diagnosed the patient to have primary liver cancer, and suspected intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma preoperatively. We performed a central hepatectomy. According to the immunohistochemical findings of the resected specimen, the tumor was diagnosed to be a primary neuroendocrine carcinoma in the liver. The patient is presently alive without recurrence at 3 months after hepatic resection.

Primary neuroendocrine tumors develop in organs or tissues that contain neuroendocrine cells. Most of the reported cases are carcinoid tumors.1 Gastrointestinal tract neuroendocrine tumors often metastasize to the liver,2 but primary neuroendocrine carcinoma in the liver is extremely rare, and there are only 22 reports of the clinical and pathologic features of primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma in the English literature.3 In addition, reports on primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma are scarce in the Korea.

Primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumors are found in adults with the mean age of older than 40 years. It occurs with a slightly higher incidence in women. When symptomatic, patients present with abdominal pain and/or palpable hepatic mass. It is difficult to preoperatively differentiate primary neuroendocrine carcinomas in the liver from other solid tumors, especially hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Associated typical carcinoid syndrome is uncommon. Metastases to bone and lymph nodes occur more often than to lung.4

In the present case, several examinations showed that there was no primary lesion outside the liver. We herein report a successfully resected case of a primary neuroendocrine carcinoma in the liver.

A 67-year-old woman was admitted to our department at Samsung Medical Center under the suspicion of a large hepatic tumor. Her main symptom was nausea. Abdominal ultrasonography had revealed a huge mass measuring 9 cm in diameter in the liver before admission. An ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration of the liver was performed at our hospital, and a pathological examination of a specimen demonstrated a poorly differentiated carcinoma. She did not have a history of operation, smoking, or alcohol use. The patient had no symptoms of hormonal dysfunction, and the laboratory tests did not reveal any liver dysfunction. The physical examination revealed palpable abdominal mass in right upper quadrant. Laboratory data, including liver function tests, were within the normal limits. The serum α-fetoprotein, PIVKA-2, carcinoembryonic antigen, and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 levels were within the normal range. She was negative for hepatitis B antigen and anti-hepatitis C virus antibodies. No endocrine studies were performed.

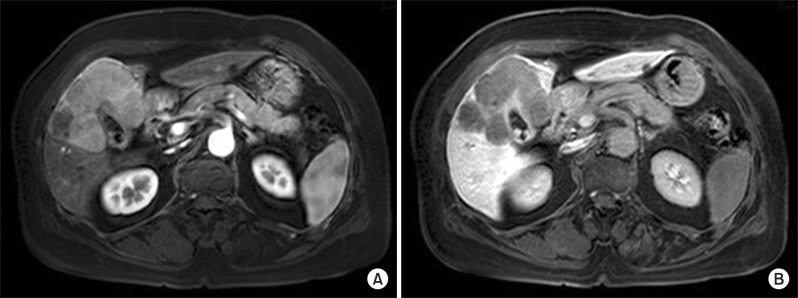

Computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a well enhanced mass measuring 9 cm in size in Couinaud's hepatic segments 4, 5, and 8. The mass showed heterogeneous arterial enhancement and washout of the tumor. The large tumor had round shape, but not invaded the hepatic vessels (Fig. 1). Lymphadenopathy around common hepatic artery was shown in the images. There was no evidence of liver cirrhosis. Upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy showed no suspicious malignant lesions.

Although the patient's tumor was located in central portion of the liver, in contact with the hilum and gallbladder, extrahepatic disease was not identified in the radiologic examinations and the patient's hepatic reserve and general condition were tolerable. Central hepatectomy and cholecystectomy were performed and lymph node dissection around hepatoduodenal ligatments was also performed. The length of the surgery was 248 minutes and blood loss during the procedure was 200 ml. The patient's postoperative course was uneventful, and she was discharged on the 15th postoperative day. Currently, she is in tolerable condition without recurrence at 3 months after the operation.

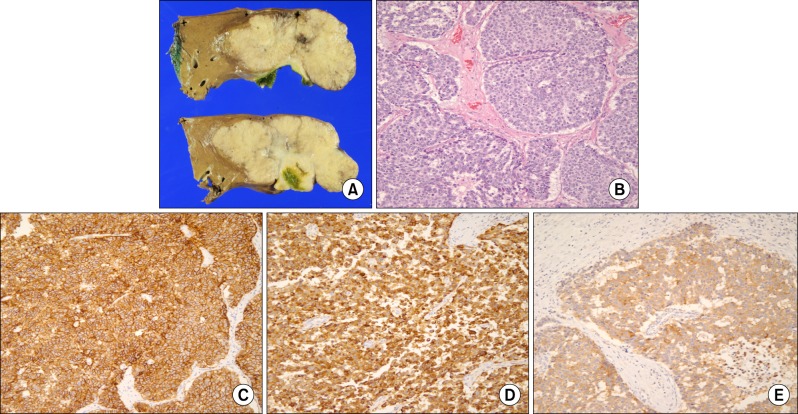

The macroscopic cut surface showed a 10.5×10×5 cm tumor. Tumor size was 9×9 cm and tumor invaded gallbladder. The surrounding liver parenchyma did not show fibrosis or cirrhosis. There were clusters of small round tumor cells arranged in sheets, marked nuclear atypia, and frequent mitoses. Lymphovascular invasion and perineural invasion were noted. One from 4 regional lymph nodes was positive for metastasis. Based on the histological findings, this tumor was classified as T4N1M0, Stage 4, according to the criteria of primary liver cancer of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). The tumor cells were immunohistochemically positive for chromogranin A, CK19, CD56, and synaptophysin. The Ki-67 positive value was 40% (Fig. 2).

To confirm that the tumor was a primary neoplasm of the chest and abdominal CT were also performed. These examinations failed to reveal a primary lesion outside the liver. Finally, we diagnosed the patient to have a primary neuroendocrine tumor in the liver and classified the cancer as a well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma based on the immunohistochemical findings.

Gastrointestinal tract neuroendocrine carcinoma is often metastasized to the liver, but primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma is rarely seen. Neuroendocrine carcinoma is described as a malignant epithelial neoplasm of the gastrointestinal tract with a predominantly neuroendocrine differentiated pattern that is different from carcinoid, atypical carcinoid, and adenocarcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation.1 The majority of neuroendocrine carcinoma cases do not have any background liver disease such as hepatitis or cirrhosis.5 Most patients are discovered by health examination with a solid liver mass.6

No preoperative diagnostic methods or therapeutic strategies for a primary neuroendocrine carcinoma in the liver have been established. Huang et al. reported that the identification of a solid tumor with cystic changes was helpful in making a differential diagnosis.7 However, we did not find a cystic change on CT and MRI in the present case. It is difficult to differentiate primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma from other solid tumors, especially hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), before operation; meanwhile, arguments still occur on the value and risk of liver biopsy.

Postoperative pathologic examination is the main method for a final diagnosis. Neuroendocrine carcinoma is diagnosed when the tumor shows diffuse cell proliferation without these typical histologic patterns.4 Chromogranin A is considered the most useful marker to confirm neuroendocrine tumors, such as NEC and carcinoid tumors. Chromogranin A is widely distributed in the endocrine and neuronal cells, and is cleaved to different bioactive peptides such as vasostatin, β-granin, chromostatin, and pancreastatin.8 In the present case, chromogranin A was positive, and frequent mitotic cells and an atypical histologic pattern were observed. Therefore, the tumor was diagnosed as NEC. However, there is no consensus on the diagnostic methods that can be used to distinguish a primary NET in the liver from metastatic NET in the liver.

Until now the most effective therapy for primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma is hepatectomy. The 5-year recurrence-free survival rate and overall survival rate of patients with NEC after hepatic resection was 19% and 78%, respectively, with median observation of 40 months.3 Further studies are needed to more accurately determine the clinical features of neuroendocrine carcinoma.

In summary, a rare liver primary tumor, primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma has a unique specificity during its occurrence and development. Final diagnosis mainly depends on pathological and immunohistochemical examinations. We need to develop more convenient and effective features in imaging and laboratory detection to differentiate primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma from HCC, hemangioma, and other solid liver masses. For patients with normal tumor marker levels who have no history of chronic liver disease, primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma needs to be ruled out.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

1. Gould VE, Jao W, Chejfec G, et al. Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1984; 1:13–18. PMID: 6400627.

2. Knox CD, Anderson CD, Lamps LW, et al. Long-term survival after resection for primary hepatic carcinoid tumor. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003; 10:1171–1175. PMID: 14654473.

3. Mima K, Beppu T, Murata A, et al. Primary neuroendocrine tumor in the liver treated by hepatectomy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2011; 41:1655–1660. PMID: 21969201.

4. Pilichowska M, Kimura N, Ouchi A, et al. Primary hepatic carcinoid and neuroendocrine carcinoma: clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of five cases. Pathol Int. 1999; 49:318–324. PMID: 10365851.

5. Ishida M, Seki K, Tatsuzawa A, et al. Primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma coexisting with hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis C liver cirrhosis: report of a case. Surg Today. 2003; 33:214–218. PMID: 12658390.

6. Donadon M, Torzilli G, Palmisano A, et al. Liver resection for primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumours: report of three cases and review of the literature. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006; 32:325–328. PMID: 16426802.

7. Huang YQ, Xu F, Yang JM, et al. Primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: clinical analysis of 11 cases. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2010; 9:44–48. PMID: 20133228.

8. Hendy GN, Bevan S, Mattei MG, et al. Chromogranin A. Clin Invest Med. 1995; 18:47–65. PMID: 7768066.

Fig. 2

Pathologic examination of primary hepatic neuroendocrine carcinoma. (A) The tumor was 10.5×10 cm size; (B) hematoxylin-eosin staining showing tumor cells (original magnification ×200); (C-E) immunohistochemical staining for CD56 (C), chromogranin A (D), and synaptophysin (E) (original magnification ×200).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download